In a Nation Paralyzed by a Pathogen, Deep Cleaners Have Their Day

As it travels between hosts, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, appears as a tiny, spiky orb, around 120 billionths of a meter across. Expelled from the human body – by a cough, say, or a well-placed sneeze – the virus can settle on surfaces, where it sits, microscopic and immobile, for hours or even days. If something comes along and touches the surface, the virus can travel with it – to a human hand, then from a hand to a face, and from there into the body.

Unless, that is, something destroys it first.

“We’re working 24 hours,” said Reuven Noyman, the owner of NYC Steam Cleaning, which has four crews sanitizing buildings across New York City and the suburbs. Standing in a client’s gym in Gravesend, Brooklyn, Noyman gestured to one of his lead technicians, Harrison Marx, an actor who cleans to pay his bills. “He was working until one o’clock at night last night.”

|

Got questions or thoughts to share on Covid-19? |

As the Covid-19 pandemic overwhelms hospitals and shuts down American cities, it has also placed new demands on janitors and specialized cleaners. “They’re overwhelmed. They’re being called all the time,” said Patty Olinger, the executive director of the Global Biorisk Advisory Council, a division of ISSA, a cleaning industry trade association.

Cleaners with no experience with disinfection, Olinger said, are suddenly being asked to treat buildings. And opportunists are rushing to open new businesses to serve the boom in demand – an effort sometimes hampered by a shortage of equipment. The lack of experience worries Olinger. “To really clean, from a scientific standpoint, from a technique standpoint, is really an art for a lot of folks,” she said. An inept cleaner will miss pathogens. And taking off protective equipment incorrectly can expose cleaners to infection — something Olinger saw while working during the Ebola crisis.

In recent weeks, GBAC has rushed out online trainings and certifications to help prepare frontline workers during the pandemic. And for many Americans, that often-invisible work has suddenly come to seem essential, as officials scramble to contain the virus pandemic and people grapple with fears of a lurking pathogen.

Noyman’s crews do use cloth and elbow grease to clean, but their core business involves more specialized equipment. They lug 100-pound carpet cleaners up stairs. They hose down whole rooms with jets of scalding steam from a $4,900 Italian-made machine. They also use spray guns that mist surfaces with electrically-charged droplets of a chemical disinfectant.

Crews like this one are now servicing Wall Street offices, buses, and schools. Just recently, Noyman said, they have treated a Ferrari dealership; the embassy of a large island nation; the five-story office of a Chinese bank; the headquarters of a trendy fitness startup; and a fleet of delivery trucks parked in New Jersey. They work for A-listers who live in eight-figure apartments and make them sign non-disclosure agreements.

Four weeks ago, when Noyman started getting Covid-19-related calls, it was just people taking precautions: We’re worried about the virus, please come clean our office. That soon changed. “The last week, every place we’re going to had a case,” Noyman said. There was a building with a doorman who got sick; a crew deep-cleaned the lobby. A nail salon called after a customer tested positive. Noyman sent a crew.

Standing in the Gravesend gym, Noyman, Marx, and another technician at the company, Samuel Esquivel, demonstrated some of their equipment.

The steam cleaner is bulky but simple: essentially a water tank, a 5-liter stainless steel boiler, a heating rod, and a nozzle. The hot cone of steam, emerging at 220 to 240 degrees Fahrenheit, scalds a surface and quickly cools. Marx and Noyman have scars on their forearms from brushing the hot tip.

These are busy times for companies like NYC Steam Cleaning. Here, the company has been hired to disinfect a local gym in Brooklyn.

The electrostatic sprayers are lighter and more nimble, but they require more care: the sprayer wears a respirator and now, in places with the potential presence of Covid-19, full-body ProGard coveralls. Crews enter a potentially contaminated building in full gear, and they often spray themselves down before undressing, in case they’ve picked up something on the way. Each device mists a solution of chlorine-based disinfectant – essentially, bleach or a close chemical relative. As the mist emerges from a nozzle, a small electrode near the tip applies a powerful electric charge to the spray. The charge causes the spray droplets to repel each other, but to be attracted to virtually any other surface around, like hair clinging to a staticky balloon.

The attraction is strong enough that the droplets, each around 400 times larger than a coronavirus, will actually float upward and coat the undersides of surfaces.

“The charge helps [the droplets] line up next to each other and not pool or puddle, so they cover surfaces completely,” wrote Heidi Wilcox, a microbiologist and commercial cleaning consultant, in an email. The user can “wave the sprayer under a hospital bed and it will get into the cracks and small spaces of the springs and other parts of the bed.”

Once there, the chemicals begin to act on any microbes. Chlorine is a powerful oxidizer, meaning it snags electrons from other molecules, unraveling proteins and damaging membranes. Once there, given enough time, these disinfectants will damage the virus, neutralizing it.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine last week found that SARS-CoV-2 can persist on some surfaces for up to three days in amounts sufficient to get someone sick. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests that people concerned about spreading the virus regularly wipe down frequently touched surfaces, like doorknobs and light switches, with a strong disinfectant.

Whether full-room disinfections are necessary is not always clear. Certainly, it’s not sufficient to keep a space safe: The virus can also be transmitted from droplets floating in the air, not just surfaces. As Noyman points out, the moment cleaners leave, passers-by begin to undo all their work.

And some cleaning methods have only mixed support. The Environmental Protection Agency has put out a list of approved disinfectants for use against SARS-CoV-2, but the list currently only includes chemicals. Olinger said that, based on current evidence, while steam can kill the virus, it needs a lengthier application time than some users may realize. “At this point during the pandemic I would not use steam at all,” Wilcox wrote, citing a lack of strong evidence. Some industry representatives, including Wayne Delfino, whose family owns Advanced Vapor Technologies of Everett, Washington, however, insist that dry steam vapor works. The company’s non-chemical, “Thermo Accelerated Nano Crystal Sanitation” technology, he wrote in an email, “has been tested and proven effective on harder-to-kill viruses and on a similar human coronavirus in seven seconds or less.”

While opinions vary, thorough cleaning of any kind can offer some peace of mind – and many techniques do kill pathogens. “Any time you can minimize your exposure, you’re helping yourself out,” said Jonathan Sexton, an environmental microbiologist at the University of Arizona who studies disinfection.

As SARS-CoV-2 spreads through New York, demand for cleaning is high. Meeting that demand may only get more challenging. Some of Noyman’s staff are already working 16 and 17-hour days. It is getting difficult to secure the chemicals they use in electrostatic systems. Noyman recently ordered a truckload, and received only five boxes. He’s being careful with what stock he has. “I’m not keeping them in trucks,” Noyman said. “I’m keeping them in the warehouse in case someone breaks into a truck.”

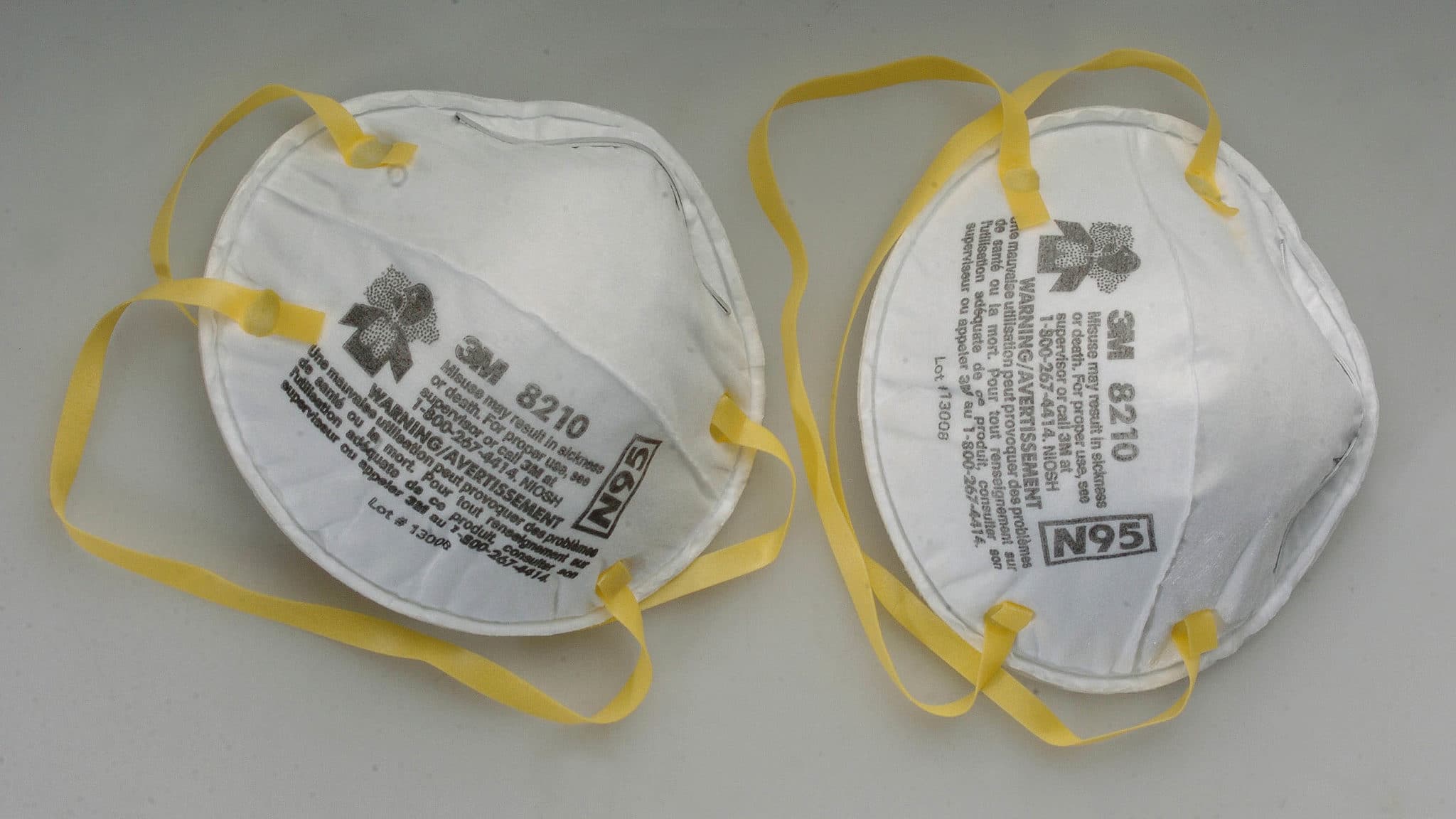

“People are stealing anything they could now,” he added. “We’re not leaving masks in the truck.”

For now, work continues, as crews chase the virus all over the country’s biggest city and pandemic epicenter. Over the years, Noyman said, it can feel like he has been everywhere. “It’s a big city,” he said, “but it’s not that big.”

This story was jointly produced by Scientific American and Undark

Jeffrey DelViscio is senior multimedia editor at Scientific American.

UPDATE: A previous version of this piece described the SARS-CoV-2 virus as being between 50 and 200 billionths of a meter across. While this range was cited in a paper in The Lancet, its original source is unclear. Other sources estimate the size at around 120 billionths of a meter. The piece also incorrectly described cleaners as “chloride-based” instead of “chlorine-based.” In describing the EPA’s list of disinfectants for use against SARS-CoV-2, the piece failed to make clear that only chemicals are included. The piece also did not provide enough context for the different types of steam application systems available. The story has been modified to address these issues.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

We already drown in chemicals and so more are unleashed. Health will decline even more and make people more vulnerable to disease.

No, I wouldn’t use steam as shown here either. According to the article, they are even adding chemistry.

Unfortunately, this is one more article of the same misinformation that is usually spread when it comes to “steam” cleaning.

People used to wonder why the original owner would become so irritated when someone called our equipment a “steam” cleaner. It was because words matter. A steam cleaner operates differently than a dry steam vapor system. People should not be confused thinking all steam is the same or that the equipment is operated in the same way. Many “steam” cleaners soak areas with water where dry steam does not. Many steam cleaners use pressure and steam to blow debris off, not true with a steam vapor system.

Our equipment has gone through substantial testing over many years using Nationally Recognized Test Laboratories. The equipment has been tested and peer reviewed by Universities. All tests showing disinfection in 7 seconds or less.

Once again words matter, and most people using the phrase “steam cleaner” are unaware of the differences between a steam cleaner and a dry steam vapor system.

The word steam has been misused by the cleaning industry. Carpet cleaners that “steam” clean your carpet. Wet chemical extraction vacs called “steam” cleaners. And the list goes on.

Randy Zielsdorf

Currently the EPA regulates pesticide products, not devices. A pesticide product contains a chemical that is intended to destroy a pest. A device uses physical means such as electricity. A steam cleaner uses electricity and water (H2O is not considered a pesticide product), therefore it is not regulated by the EPA and will never be on any approved pesticide product list so long as the rules remain as they are. If a device, such as a steam cleaner, is making claims, the EPA recommends the manufacturer have the scientific data to support them.

Utilizing a proprietary attachment the Advance Vapor product does have an EPA # as a disinfecting device. I am a 45 year veteran of the cleaning industry. One of my mentors early on was involved with early floor coatings while working with a major flooring manufacturer and as a research scientist was also instrumental in the creation of the transformation from virucides to safer germicides. While I am not degreed I learned from one of the best. Therefore, teaching disinfection has always been in the forefront. I worked with hospital systems throughout North Carolina an beyond. One reference is the University of North Carolina system. I installed dozens of the vapor systems discussed earlier in many departments to include OR. Yes, OR. The test samples taken in various places in the OR were sent to Ecolab. The steam vapor system removed the residue from the high-dollar disinfectant that remained after it dried. When I teach disinfection today I’m amazed how many people (even in healthcare) are not aware that there are three steps: clean, disinfect and rinse. Why rinse? Alkaline products leave behind a biofilm when they dry. This biofilm becomes a food source. The steam cleaning w/chemicals described in this article are leaving behind the biofilm I just discussed. The steam vapor system with the aforementioned attachment accomplish these three steps in one application. I did the NOROVIRUS test myself in 2005 at a lab in Virginia. 7 seconds to ZERO. Why take chances?