The Worrying Murkiness of Institutional Biosafety Committees

In 2004, an activist named Edward Hammond fired up his fax machine and sent out letters to 390 institutional biosafety committees across the country. His request was simple: Show me your minutes.

Few people at the time had heard of these committees, known as IBCs, and even today, the typical American is likely unaware that they even exist. But they’re a ubiquitous — and, experts say, crucial — tool for overseeing potentially risky research in the United States. Since 1976, if a scientist wants to tweak the DNA of a lab organism, and their institution receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, they generally need to get express safety approval from the collection of scientists, biosafety experts, and interested community members who sit on the relevant IBC. Given the long reach of the $46-billion NIH budget, virtually every research university in the U.S. is required to have such a board, as are plenty of biotechnology companies and hospitals. The committees “are the cornerstone of institutional oversight of recombinant DNA research,” according to the NIH, and at many institutions, their purview includes high-security labs and research on deadly pathogens.

The agency also requires these committees to maintain detailed meeting minutes, and to supply them upon request to members of the public. But when Hammond started requesting those minutes, he found something else. Not only were many universities declining to share their minutes, but some didn’t seem to have active IBCs at all. “The committees weren’t functioning,” Hammond told Undark. “It was just an absolute joke.”

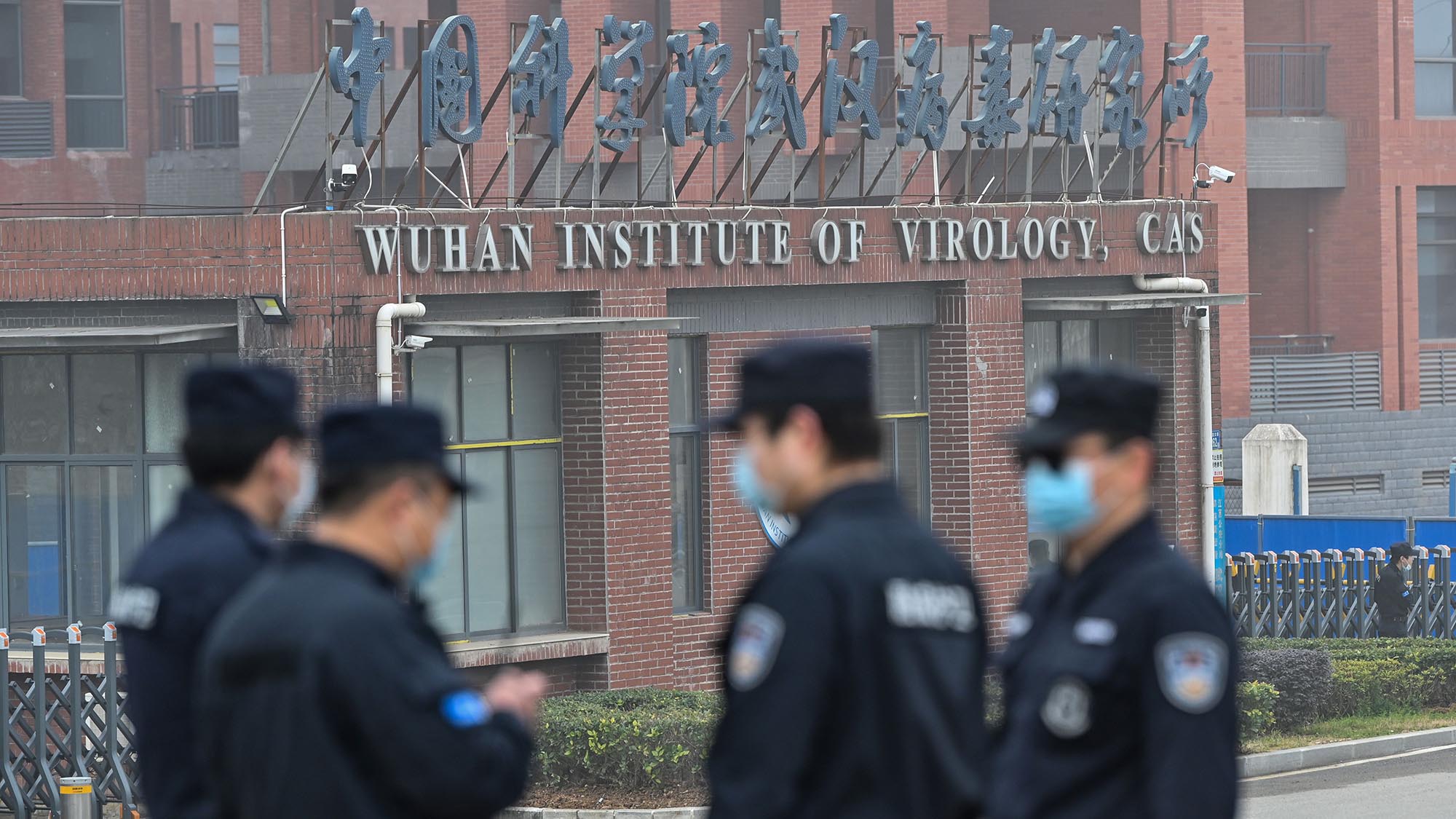

The issue has gained fresh urgency amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Many scientists, along with U.S. intelligence agencies, say it’s possible that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, emerged accidentally from a laboratory at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, or WIV — a coronavirus research hub in China that received grant funding from the NIH through a New York-based environmental health nonprofit. Overseas entities receiving NIH funding are required to form institutional biosafety committees, and while grant proposals to the NIH obtained by The Intercept mention an IBC at the Wuhan institution, it remains unclear what role such a committee played there, or whether one was ever really convened.

An NIH spokesperson, Amanda Fine, did not answer questions about whether the Wuhan institute has had a committee registered with the agency in the past. In an email, she referred to a roster of currently active IBCs, which does not list WIV. Other efforts by Undark to obtain details about meetings of the Wuhan lab’s IBC were unsuccessful. But so, too, were initial efforts to obtain meeting minutes from several IBCs conducting what is supposed to be both routine and publicly transparent business on U.S. soil. Undark recently contacted a sample of eight New York City-area institutions with requests for copies of IBC meeting minutes and permission to attend upcoming meetings. Most did not respond to initial queries. It took nearly two months for any of the eight institutions to furnish minutes, and some did not provide minutes at all, suggesting that in many cases, the IBC system may be as opaque and inconsistently structured as when Hammond, who eventually testified before Congress on the issue in 2007, first began investigating.

Indeed, recent interviews with biosafety experts, scientists, and public officials suggest that IBC oversight still varies from institution to institution, creating a biosafety system that’s uneven, resistant to public scrutiny, and subject to minimal enforcement from the NIH. Hammond and other critics say these problems are baked into the system itself: As the country’s flagship funder of biomedical research, the NIH, these critics say, shouldn’t also be charged with overseeing its safety.

For its part, NIH has argued that as an agency intimately involved in reviewing the complex details of biomedical research, it is well-suited to manage the network of committees ostensibly set up to help ensure the safety of that research. And the IBC system, the NIH says, is just one part of a multi-faceted biosafety apparatus. “They play an incredibly important part,” said Jessica Tucker, acting deputy director of the Office of Science Policy at NIH, “in this interlay of local and federal oversight.”

In some jurisdictions, including the research-heavy corridors of Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, the addition of local policies and oversight structures has provided a comparatively clear view of the potentially hazardous biomedical science undertaken there. But the wider network of IBCs remains far more opaque, and insights into how well they operate, or even whether they operate, remains unacceptably difficult to discern, Hammond and other critics say — perhaps even more so as a rising crop of for-profit companies offer IBC services to clinical research sites for a fee.

In recent interviews with Undark, biosafety professionals variously described Hammond as “kind of an asshole” and “like a bulldozer”— though those same experts also acknowledged that he has identified real issues. “A lot of what he’s saying makes sense,” said David Gillum, the chief safety officer for Arizona State University and a past president of ABSA International, the flagship professional organization for biosafety specialists in the U.S. Many people in the biosafety community, Gillum said, would agree that “the NIH, if it’s conducting the research — maybe they shouldn’t be self-policing.”

Altering the DNA of microbes and other organisms can bring incalculable social benefits, including new insights into pathogens, new tools for synthesizing drugs, and the development of lifesaving vaccines. Much of it poses little, if any, risk. But it can also, in some cases, involve potential hazards: A pathogen might escape, a lab worker or research subject might be harmed, or a genetically altered organism might spill into the wild without appropriate vetting.

Lab accidents involving pathogens do happen, though most are minor. In rare cases, laboratory workers suffer serious harm or die. Occasionally, incidents can have even broader consequences: Many scientists believe a flu pandemic in 1977 may have originated from an accident at a Soviet lab — though researchers have suggested other explanations in recent years. People sometimes hijack research for nefarious ends, too: The perpetrator of the 2001 anthrax attacks in the U.S., which killed five people, was almost certainly a federal laboratory worker with access to the bacteria and lab equipment.

In response to such risks, the U.S. has developed a range of methods to improve biosafety, which applies to accidents, and biosecurity, which applies to intentional misuses of the technology. In addition to IBCs, some institutions with large research operations employ biological safety officers, whose jobs include inspecting labs, advising researchers on safety practices, preparing materials for IBC review, and, sometimes, serving as IBC members. Research with some pathogens and toxins requires additional review from federal agencies — including background checks for employees and rigorous specifications for lab spaces. Those requirements are backed by the force of law, and are administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In the biosafety system, the IBC is a kind of local court, overseeing the implementation of the 149-page NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules. “We get thousands of emails every year with questions,” the NIH’s Tucker said. “So that is usually the entry point for discussions with IBCs about challenges that they may be facing.”

Much of this system emerged in the 1970s, after Paul Berg, Janet Mertz, and other researchers at Stanford University developed a technique to insert pieces of foreign DNA into E. coli bacteria. Scientists had a new power that could be used to engineer organisms with novel properties. But with that power came risk. “There is serious concern that some of these artificial recombinant DNA molecules could prove biologically hazardous,” a panel of prominent scientists, chaired by Berg, wrote in Science in 1974. Among other scenarios, they worried about the escape of a bacteria engineered to resist antibiotics.

The next year, the National Academy of Sciences convened a meeting, chaired by Berg, at the Asilomar Conference Center in California. Despite some calls to include laboratory technicians, custodians, and other members of the public, the Asilomar participants were mostly senior scientists, along with a few lawyers and public officials. The discussion laid out a roadmap for biosafety in the U.S. Notably, an official summary of the proceedings did not include the word “regulation.” The NIH Guidelines, issued in 1976, are just that — guidelines, rather than regulations with the force of law. If any of those requirements aren’t met, NIH can demand changes, and, at least in theory, pull funding.

“In essence, the goal was self-governance,” wrote Susan Wright, a research scientist emerita in the history of science at the University of Michigan, in a 2001 paper on Asilomar and its legacy. The guidelines allow institutions to largely police themselves, with the IBC exercising oversight for most research. When Sen. Edward Kennedy, a Massachusetts Democrat who passed away in 2009, proposed a bill that would hand the power of regulating genetic engineering to an independent commission, Wright said, major scientific organizations rallied to defeat the proposal.

The prospect of NIH oversight did not immediately reassure residents of Cambridge, Massachusetts, a major scientific research hub. In 1976, amid public alarm about a newly proposed virus and genetics laboratory at Harvard, the city council held a hearing on recombinant DNA research. At a packed meeting, some council members were skeptical that the NIH was equipped to handle the issue. “We’re gonna find ourselves in one hell of a bind,” said councilmember David Clem, “because we are allowing one agency with a vested interest to initiate, fund, and encourage research, and yet we are assuming that they are non-biased and have the ability to regulate that and, more importantly, to enforce the regulations.”

The city went on to pass its own biosafety regulations, enforcing compliance with NIH standards. In the years that followed, however, few other municipalities followed suit.

At a packed city council hearing in Cambridge, council members discuss the safety of recombinant DNA research with scientists, including the molecular biologist Maxine Singer, who attended as a representative of the NIH.

Video: MIT/J. Christopher Anderson

Edward Hammond founded The Sunshine Project, a bioweapons watchdog group, in 1999, along with a German colleague. They figured the subject would stay relatively obscure. Then the September 11 attacks happened, followed by the anthrax scare. In response, the George W. Bush administration and Congress poured billions of dollars into preparing for a bioterrorist attack. The number of laboratories studying dangerous pathogens ballooned.

When Hammond began requesting minutes in 2004, he said, he intended to dig up information about bioweapons, not to expose cracks in biosafety oversight. But he soon found that many institutions were unwilling to hand over minutes, or were struggling to provide any record of their IBCs at all. For example, he recalled, Utah State was a hub of research into biological weapons agents. “And their biosafety committee had not met in like 10 years, or maybe ever,” Hammond said. “They didn’t have any records of it ever meeting.”

Other sources from the period after the 9/11 attacks suggest that institutions were often flouting the NIH Guidelines. In 2002, 2007, and 2010, a group of researchers conducted surveys of hundreds of IBCs. Of the IBCs that responded, many were failing to train their members, and many were conducting expedited reviews of research without full committee input — both violations of NIH requirements. In the 2010 survey, nearly 30 institutions reported that they had no formal process to ensure that relevant experiments even received an IBC review.

The NIH has sometimes cracked down on institutions. In 2007, a young insect geneticist, Zach Adelman, joined the IBC at Virginia Tech. Not long after, the NIH determined the IBC was not functioning properly, and made the committee members go back and re-evaluate all relevant research on campus.

Adelman, who is now a professor at Texas A&M University, was eventually appointed the chair of the committee. The position, he said, was grueling, but also rewarding. Working closely with biosafety staff, Adelman would assess research protocols — each 50 to 100 pages long — and assign them to committee members with relevant expertise for review. If nobody at the institution had relevant experience with a particular pathogen or protocol, he’d shop the proposal out to someone at another institution. During meetings, the group would assess the experience of the researcher, their laboratory space, their training — all to gauge whether the scientist seemed equipped to do the experiment in a way that was safe for lab workers and the community.

It took some time, Adelman said, for researchers to adapt to the new oversight. “We were coming from a point where the IBC wasn’t really reviewing things well,” he said; principal investigators were accustomed to their research proposals undergoing “minimal review, rubber-stamping.”

At the time he became chair, Adelman was seeking tenure — an arduous process that requires approval from more senior peers. His IBC position, he said, sometimes required him to tell senior researchers that their work wasn’t meeting the bar. The interactions could grow confrontational. But, he said, the experience convinced him that IBCs can be effective, with a committed chairperson and strong university support.

Some experts say such support is lacking at some — perhaps many — institutions. IBC oversight is “a very uneven system,” said Richard Ebright, a molecular biologist at Rutgers University and a longtime critic of U.S. biosafety policy. (Ebright has served for 20 years on the Rutgers IBC, which he says functions well.)

Overall, Ebright says, the system is vulnerable to abuse. “It’s a mechanism that delegates full responsibility for evaluating, assessing, and improving research protocols to the institution that will perform them,” he said. “As a result, of course, it’s a policy that has inherent, built-in conflict of interest.” In that structure, he argued, lax oversight should not be a surprise: “It’s all the expected, indeed the intended, result of having a program that is voluntary, not monitored, and not enforced.” Ebright argues that biosafety should be governed by laws or regulations, not guidelines, with monitoring and enforcement supplied by an independent federal agency other than the NIH.

|

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive. |

Some biosafety experts say the existing incentives do push institutions to prioritize biosafety. “It does not behoove an institute or an institution to be complacent with a weak IBC and program,” said Barbara Johnson, a biosafety and biosecurity consultant and a former federal employee. “There’s just too many places where that can lead to trouble.” While some institutions may not have strong biosafety programs in place, she said in her experience it’s rare.

Tucker, the NIH official, formerly led the Office of Science Policy’s biosafety and biosecurity division. When her team identified problems with biosafety oversight at an institution, she said, NIH staff could intervene. The agency, she said, is well-positioned to offer oversight. “It is the mission of the [NIH] to responsibly fund research,” she said, “and the ‘responsible’ portion is where the oversight function comes in.”

Still, Tucker acknowledged that the NIH does not perform audits of IBCs to ensure that they’re functioning, or offer other proactive oversight. “You know, we don’t conduct audits, because that isn’t really our role as a funder,” she said. “In this space, our role is to work with the institutions to deal with any compliance issues as they arise.”

In principle, another major role of IBCs is allowing members of the local community to participate in discussions about research in their cities and neighborhoods. Institutions must appoint two unaffiliated community members to their IBCs, for example. And in addition to the requirement to share meeting minutes upon request, the NIH Guidelines encourage IBCs to open up their meetings to the public “when possible and consistent with protection of privacy and proprietary interests.” One 2014 NIH memo says that “the principles of public participation and transparency” are integral to the program.

In practice, though, IBC community members are often scientists or biosafety experts themselves, and many committees are resistant to sharing minutes. Public attendance at meetings — when permitted at all — appears to be rare.

“I don’t think that mission that NIH had in mind is fulfilled anywhere,” said Adelman.

When Undark contacted the New York city area IBCs in mid-October to request recent minutes and the opportunity to attend an upcoming meeting, few committees initially responded. An email to the listed public contact address for the Albert Einstein College of Medicine IBC bounced; it only accepted messages from approved senders or people inside the institution. Six weeks later, despite repeated follow-up notes, none of the eight institutions had supplied minutes. The IBC at SUNY-Downstate did not reply to messages at all.

Eventually, four institutions — Columbia University, New York Medical College, New York University Langone Health, and Rockefeller University — sent minutes and invitations to a meeting. (Shortly before publication of this article, a fifth institution, Weill Cornell Medicine, said IBC minutes were ready to be mailed after a nearly five-month wait.) The three IBC meetings Undark observed involved brisk discussions about a wide range of research. At NYMC, committee members debated whether a specific study involving adeno-associated viruses should be conducted in a BSL-1 or BSL-2 facility. At NYU Langone, the committee considered a laboratory’s request to start working with a strain of SARS-CoV-2 that was adapted to infect mice — were the safety protocols appropriate? And on the Columbia committee, a community member with clinical research expertise raised concerns about whether a laboratory requesting permission to study both SARS and MERS coronaviruses had sufficient procedures in place to prevent the two from mingling.

Even then, institutions appeared concerned about the presence of a reporter. At Columbia University, which conducts biomedical research in upper Manhattan, officials appeared apprehensive about the prospect of a reporter attending a meeting, and a spokesperson, Christopher DiFrancesco, initially declined Undark’s requests to attend a November session. At NYU Langone, the institution required a reporter to travel to a conference room in midtown Manhattan to attend the meeting. A communications staffer, a biosafety office administrator, and a member of the legal counsel’s office were also present in the room — even though the IBC meeting was entirely virtual. (Lisa Greiner, a spokesperson for NYU Langone Health, said the in-person requirement would extend to any member of the public, not specifically journalists.)

Outside New York, some research centers — Georgia State University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Vanderbilt University — were quicker to supply minutes. Others were less easy to reach: At San Antonio’s Texas Biomedical Research Institute, the only private institution in the United States to host a BSL-4 lab — meaning it’s capable of working with the most dangerous pathogens — the IBC lists only a phone number on its website, which goes to a general menu for the institute.

Many biosafety experts caution that transparency can have costs. Some recombinant DNA research, for example, is subject to opposition by activist groups, and researchers may fear public backlash. These fears may have only intensified amid recent reports of harassment and threats directed at virologists and other scientists.

Sharing other details, such as the locations of certain labs, can also pose biosecurity risks. (The NIH permits institutions to redact minutes.) “I am all for transparency, provided it doesn’t put intellectual property at risk, it doesn’t put security at risk, or the personal security of a researcher at risk,” said Rebecca Moritz, the biosafety director at Colorado State University and president-elect of ABSA International. Her ideal, she said, is proactive communication, in which institutions explain why their research matters, and detail the steps they take to keep it safe. But, she said, “there are other institutions who are significantly more risk averse in that conversation. And they would prefer just no one to know what they’re doing.”

One exception to this approach is in the Boston area, a biotechnology hub where, 46 years after the contentious meetings at the Cambridge City Council, municipal governments retain unusual control over biosafety decisions. In both Cambridge and Boston, independent city biosafety committees can review proposed research and policies, and regulations require that anyone doing recombinant DNA research — whether or not they receive NIH funding — maintain an IBC.

In Boston, those regulations emerged from a long-running dispute over the National Emerging Infectious Disease Laboratories, or NEIDL, a high-security facility housed at Boston University. There, scientists study Ebola, SARS-CoV-2, and other pathogens. After it first received a grant in 2003, the project faced pushback from many locals, worried about risks.

In response, said Kate Mellouk, BU’s associate vice president of research compliance, the university committed to full transparency. Unusually, BU voluntarily posts all of its IBC minutes on its website. “We have no secrets,” Mellouk said. “It’s all out there.” Under Boston city regulations, all research in BSL-3 or BSL-4 laboratories requires approval from an independent biosafety committee convened by the Boston Public Health Commission. For the highest-risk research, the Boston City Council also has a 30-day period to review the proposal and raise any concerns – a power, Mellouk said, they’re yet to exercise.

The process can slow down research, and Mellouk said delays are sometimes frustrating for scientists. “The local regulations don’t necessarily provide any additional safety for the public or the community or the environment” or employees, she said, stressing that they have a warm relationship with BPHC. In an email, Leon Bethune, director of the BPHC’s Community Initiatives Bureau, wrote that the commission is working hard to streamline the approval process — and that “our presence and more frequent involvement (lab inspections) provides that extra level of local involvement and assurance that federal oversight alone cannot provide.”

Across the river in Cambridge, city officials offer free training sessions to community members who are getting ready to serve on IBCs. Sam Lipson, the senior director of environmental health for the city’s public health department and chair of the Cambridge Biosafety Committee, said the work can also help address fears in the community.

Shortly after the BSL-4 lab was approved at the NEIDL facility, he recalled, a group placed flyers on cars near MIT warning, inaccurately, of bioweapons research in the area. Lipson met two of the people behind the flyers at a public meeting. He said that he told them how Cambridge regulates local research — and then invited them to come serve on an IBC. They declined. “There was no debate after that,” Lipson said. “I never heard from them.” The approach, he said, reflects a model he’s seen work again and again in the city: respond to worried members of the public with openness, opportunities to participate, and reams of information.

“If people finally get the idea that, if you want more you’ll get more,” he said, “they just — the hunger goes away.”

Recently, the number of IBCs has quietly swelled. That’s especially true in the private sector, where a boom in the use of recombinant DNA in medicine — including gene therapy and mRNA vaccines — requires many biotechnology companies and clinics running trials to gain IBC approval.

In the past six years, a fledgling IBC-for-hire industry has emerged to meet that need. Today, just three companies collectively maintain more than 1,000 IBCs. “We’re fully compliant with NIH guidelines, we provide the same or better level of oversight as a university has,” said Daniel Eisenman, executive director of biosafety services at Advarra. The company contracts a core group of experts who serve on hundreds of IBCs, and cultivates what Eisenman calls “a large network of community members,” in every major U.S. city, who can be tapped to serve as local representatives on IBCs on short notice. The company aims to review proposals within six business days, speeding up biomedical research.

Chris Jenkins, who operates a similar model at his company, Clinical Biosafety Services, said demand is booming. Burning through his savings, he founded the company in February 2017 with just one client; today, he said, they have 37 full-time employees and operate more than 500 IBCs. Companies pay around $6,000 per year for the service, Jenkins said last November; the committee members they recruit make some $150 per meeting.

Some biologists and biosafety professionals are skeptical of the IBC-for-hire model. “I do have my concerns about them, because I wonder if they truly represent the institution and the community,” said Gillum. Companies, he noted, have even approached him to serve as a community member on IBCs, despite his role as a prominent biosafety expert. Still, he believes “they’re meeting the requirements of the NIH.” Other critics point to a possible conflict of interest in a pay-for-oversight model: A company that gets a reputation for frequently saying no could, presumably, lose business. But Eisenman disagreed. “Compensation is not affected based on the committee decision,” he said. “If anything, if there was pressure to rubber stamp or do anything inappropriate, it would ultimately hurt the reputation of Advarra, and compromise the value of the review that we perform.”

The IBC model also appears to be growing overseas. Barbara Johnson, the biosafety consultant, said she has advised clients abroad on how to institute the committees. The World Health Organization, in its nonbinding biosafety manual, recommends that institutions form IBCs as part of a suite of tools to govern potentially risky research — albeit without the transparency requirements that characterize IBCs in the U.S., and at foreign institutions receiving NIH funding.

The use of IBCs has also expanded in China, where until October 2020 the government had no unified biosafety policy. “In China, the IBCs play an increasing role in oversight and biorisk assessment of novel techniques and experiments concerning the manipulation of pathogens and recombinant DNA,” wrote infectious disease specialists Zhiming Yuan and James LeDuc in a 2019 academic article. LeDuc ran the Galveston National Laboratory, a major research center in Texas, before retiring last year. Zhiming is at WIV; he did not respond to requests for comment, but in a biography uploaded to an NIH website in 2014, he is described as the institute’s longtime IBC chair.

Whether the growing scrutiny on biosafety during the Covid-19 pandemic will prompt challenges to this model of scientific self-governance is less clear.

Ebright, who has been campaigning for reforms to U.S. biosafety policy since shortly after the September 11 attacks, believes the context has changed. Before Covid-19 arrived, he said, when someone would suggest that a particular activity could trigger a pandemic, the implications didn’t seem to sink in. “Now everyone grasps that,” he said. Recently, he said, some members of Congress have reached out to him for policy advice — virtually all of them Republicans. A change in the control of Congress in the 2022 elections, Ebright predicted, would lead to proposals for more rigorous biosafety oversight.

At issue, some analysts suggest, are questions of power: How much is the public willing to allow taxpayer-funded scientists and scientific agencies to make decisions about safety and risk, with limited public input? “At the end of the day, this is not just a lab security issue, but it’s a harm to the public or potential risks to the public kind of issue,” said Zeynep Pamuk, a political scientist at the University of California, San Diego who studies the role of science in democracies, including the regulation of high-risk research. “So it affects everybody, every citizen.”

Hammond remains jaded. Speaking with Undark in November, he described what he perceives as a domineering, macho culture in the labs that do the most cutting-edge research. Trusting institutions to maintain effective IBCs, he suggested, is just not enough. “What needs to happen is it needs to become mandatory,” he said. “And there need to be consequences if you don’t do things correctly.”

UPDATE: This piece has been updated to reference federal biosafety regulations administered by the CDC and USDA.