Scientists Square Off Over Covid, Wuhan, and Peter Daszak

On Sept. 30, a group of 10 scientists, historians, and other academics from around the world sent a letter calling for the ouster of Peter Daszak, a British zoologist, from his position as president of EcoHealth Alliance, a New York based nonprofit that works to thwart infectious disease outbreaks. Known for pioneering work on how viruses spill from wildlife into humans, Daszak had steered EcoHealth into partnering with coronavirus experts at China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology in the wake of the first SARS outbreak in 2002 to 2004. He has co-authored more than a dozen papers with researchers there and directed U.S. funding their way, including hundreds of thousands of dollars from a National Institutes of Health grant first awarded in 2014. Soon after the Covid-19 pandemic began, Daszak led the charge in dismissing allegations that its viral cause, SARS-CoV-2, could have come from the lab.

The letter calling for his removal was addressed to EcoHealth’s senior board members, top officials at the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services, and Daszak himself. It stated that Daszak, in his capacity as EcoHealth president, had “withheld critical information and misled public opinion by expressing falsehoods.”

On Daszak’s continued role as president, Gilles Demaneuf, a New Zealand-based data scientist, suggested the feelings of his fellow co-signers were unequivocal: “We reached a point where, collectively, we said, look, this is not helping anybody,” he said.

The signatories are connected to an informal collection of scientists, biosafety experts, and others dubbed the Paris group, which advocates for comprehensive investigations into the possibility of a lab leak — or more broadly what Demaneuf refers to as a research-related accident. This “also includes an infection on a field sampling trip,” Demaneuf said, adding that the group felt it was important to “clean that up and ask for what is inevitable.” The EcoHealth Alliance, Demaneuf said, “should take distance from a very compromised person.”

While the “Paris group” remains a loose and apparently varying affiliation of researchers with no fixed membership, agenda, or constituency (at least one source suggested that the name “Paris group” has no real meaning at all), experts associated with the title have been working since 2020 to influence the World Health Organization’s investigation of Covid origins. That process has been complicated from the start by a lack of access to crucial data from the Chinese government, and what the Paris group claims are unbalanced efforts to seek a zoonotic source for the pandemic that doesn’t fully consider competing scenarios. While scientists remain sharply divided over the plausibility of a lab leak versus a natural spillover, a leaked grant proposal, documents obtained under federal record act requests, and letters co-authored by Paris group members have raised questions about EcoHealth’s transparency and Daszak’s conflicts of interest — questions that have spurred a series of congressional inquiries in the U.S. and are helping to shape the content of the WHO’s next investigative team.

Daszak has irked the Paris group for months. His organization is among the most influential emerging pathogen research organizations in the world, and from the pandemic’s first days, they say, Daszak sought to cast doubt on a lab leak, even as his comments and behaviors gave the impression that he was trying to deflect attention away from some of EcoHealth’s more controversial research in Wuhan. Undark made several attempts to contact EcoHealth for comment, and requested an interview with Daszak, but received no response. Daszak’s supporters, however, say that the British researcher has been unfairly targeted.

Stanley Perlman, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Iowa, describes Daszak as a straightshooter who “cares about a really important issue, which is how to prevent zoonotic infections from occurring again.” Jamie Metzl, a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, an international affairs think tank in Washington, D.C., a co-signer of the Paris group’s letter, and a former member of the WHO’s expert advisory committee on human genome editing, counters that Daszak “leads this propaganda campaign, vilifying people who ask questions” that contradict a view that SARS-CoV-2 passed to humans from wildlife.

In an interview with Science published earlier this month, Daszak characterized criticisms of his efforts as anti-science and said, “we have done nothing wrong.”

The Paris group, Metzl says, was created in late 2020 by a small nucleus of French scientists. At the time, hypotheses that the novel coronavirus had emerged from a laboratory were largely taboo in scientific institutions and Western media, routinely dismissed as conspiracy theories. Instead, more informal, activist organizations emerged to push for further investigations into the origins of the virus. Chief among them was DRASTIC — a loose collection of internet activists, that has obtained headline-making documents about the Wuhan Institute of Virology and EcoHealth. Another was the Paris group, which shares several members with DRASTIC.

Since its formation, the group’s members, many current or retired university professors with varied backgrounds, have produced a handful of open letters criticizing the Chinese government’s heavy-handed control over investigations into Covid origins, and what they claim are unbalanced efforts to seek a zoonotic source for the pandemic that doesn’t fully consider competing scenarios. In media reports, the letters have drawn support from experts who agree with the main points, as well as dubious responses from others who believe a lab origin is nearly impossible. The Paris group has no official status. Participants convene once a month or so on video calls, and can decide whether or not they want to join in on a particular letter or activity, says Metzl.

In the letter calling for Daszak’s dismissal, signatories point to what they say are his conflicts of interest, including that he took part in investigations of Covid origins in spite of his professional history with the Wuhan laboratory. In January 2021, for instance, Daszak linked up with an investigative team convened by the WHO, which concluded after several weeks of hunting for evidence in Wuhan that a lab-related accident was “extremely unlikely.” Noting that Chinese government officials had limited access to raw data, the WHO’s director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, later recanted the team’s conclusion, saying the push to rule out a lab-leak was premature.

In the Science article, Daszak is quoted saying he at first declined to join the WHO/China mission, but changed his mind out of a sense of duty. “If you want to get to the bottom of the origins of a coronavirus outbreak in China, the No. 1 person you should be talking to is the person who works on coronaviruses in China who’s not from China,” he told Science. “So that’s me, unfortunately.”

Daszak also agreed to head up a separate Covid origins investigation, this one convened by The Lancet, a British medical journal. However, according to The Wall Street Journal, he recused himself in June. Later, Jeffrey Sachs, an economist at Columbia University, and the Lancet commission’s chair, decided to disband the whole team, in part due to conflicts of interest involving other members’ links to EcoHealth.

At the same time, as the Paris group letter points out, Daszak has repeatedly claimed there is zero evidence that a laboratory incident played a role in the pandemic, while describing explanations other than a natural origin as conspiracy theories. Daszak used this particular phrasing in a statement published in the Lancet, which Metzl describes as “scientific propaganda and thuggery.” It was subsequently parroted by journalists, pundits, and politicians who, inadvertently or not, helped to undermine the lab leak’s credibility.

Perlman, who says he does not think Daszak should be removed based on the Paris group letter, was among the Lancet statement’s 27 co-signers. He said it was written to address concerns that SARS-CoV-2 may have been bioengineered, a feat that he says isn’t possible. The lab-leak hypothesis has since morphed to include other scenarios that the Lancet statement doesn’t address, Perlman says, including that SARS-CoV-2 could have been a natural virus that somehow got into the Wuhan laboratory and then escaped.

Still, some continue to refer to those who suggest the possibility of a lab leak as conspiracy theorists, among them H. Holden Thorp, Science’s editor-in-chief, who used the term in a Nov. 11 editorial.

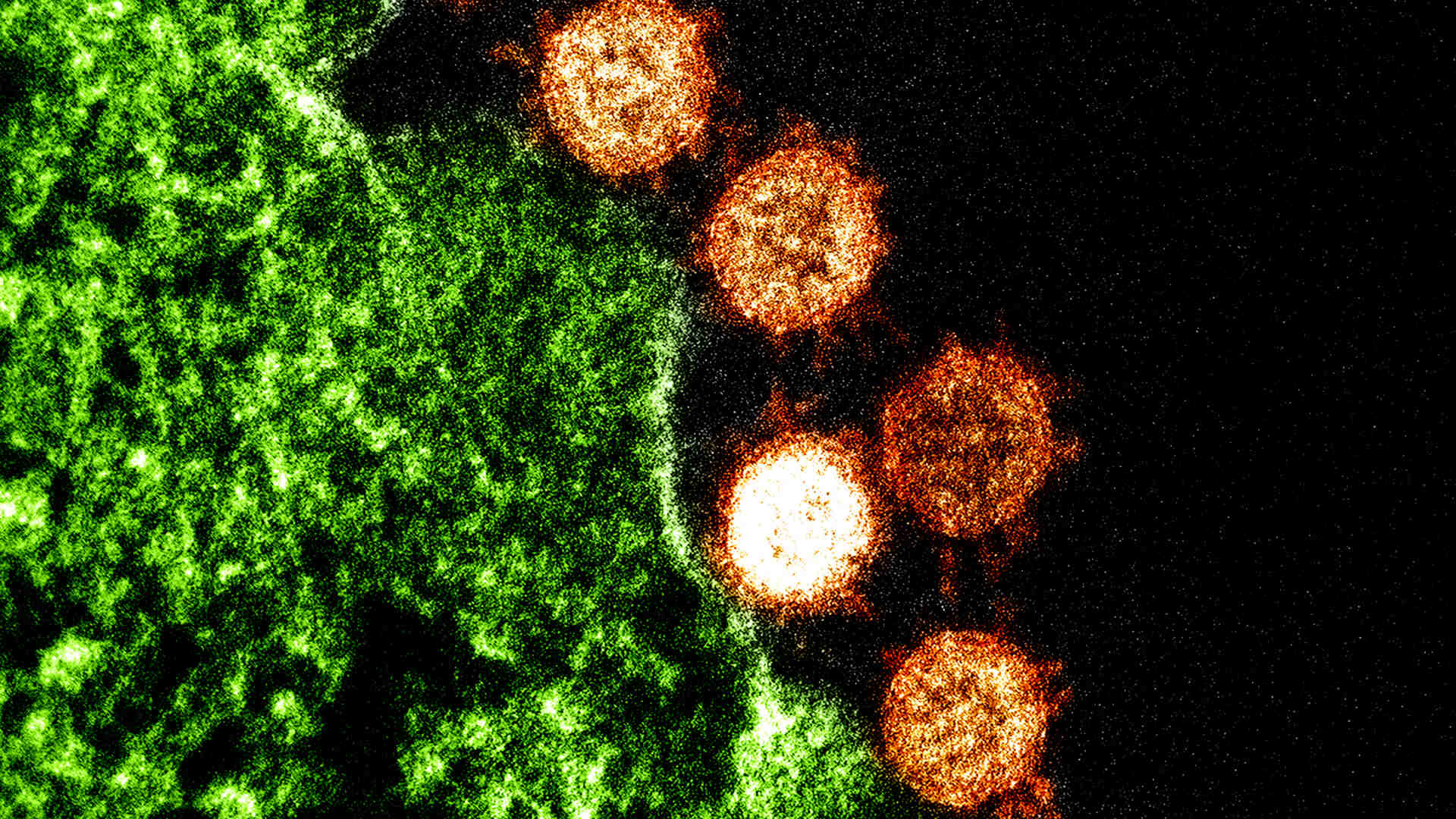

Scientists affiliated with EcoHealth and the Wuhan Institute of Virology experimented with dangerous bat coronaviruses in the years before Covid-19 arrived, and had at least proposed experiments that would alter the properties of such viruses to potentially make them better able to infect humans.

The recent Paris group open letter raised concerns about the truthfulness of some of Daszak’s public statements about that research. For example, it cites a December, 2020 tweet in which the EcoHealth president claimed the Chinese labs he worked with had never kept live bats, even though by the Wuhan scientists’ own accounts, live bats were present at the facility since at least 2009, and that lab personnel had filed patents to breed the animals. That Daszak disputed what is so clearly evident in the records, Demaneuf says, “means there is an issue about his reliability.” (According to the Science article, Daszak has since admitted he was misinformed about the presence of bats in the facility.)

Alina Chan, a postdoctoral researcher specializing in gene therapy and cell engineering at the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts who co-authored a book about Covid’s origins, is a longtime critic of EcoHealth. She points out that researchers filed a patent for bat breeding devices around the same time as the submission of a failed EcoHealth proposal which sought to, among other things, inoculate wild bats with novel coronavirus spike proteins. Called Project Defuse, the proposal was rejected by the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and never disclosed, even as EcoHealth’s connections to the Wuhan outbreak were coming under growing scrutiny, an omission that to some appears dishonest.

|

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive. |

DRASTIC posted the failed proposal online in September. Demaneuf, who is also affiliated with the group, says that DRASTIC grant reviewers were struck by the plans to put human-specific furin cleavage sites into the tell-tale spike proteins of SARS-related viruses. Furin cleavage sites enable the virus to efficiently infect human cells, potentially making it more transmissible among people (an outcome that reflects a microbial gain-of-function). Indeed, SARS-CoV-2 is unusual for having a furin cleavage site, which other coronaviruses in its class do not share.

Daszak told Science that he didn’t remember the five sentences within the 43-page proposal that describe this experiment. In Perlman’s view, controversies surrounding furin cleavage sites are overblown. “I don’t know of a situation where you get a more virulent virus,” from this sort of modification, he says. Still, some scientists, including Chan and others, see the furin cleavage research as extremely high-risk. That Daszak failed to disclose project DEFUSE, even as he was participating in organized efforts to uncover the pandemic’s origins, shows a level of “disrespect for scientific and ethical norms that is without precedent,” the Paris group members wrote.

In their letter, the Paris group also took issue with Daszak’s defense of a move by the Wuhan Institute of Virology to take of its data offline — thus making it unavailable to outside reviewers. The Wuhan laboratory started pulling its databases in September 2019, and the information remains off-limits today. During a Covid-19 briefing hosted earlier this year by the Chatham House, a London-based international affairs think tank, Daszak said the move was “absolutely reasonable,” given that the data had been subjected to more than 3,000 hacking attempts. He added that he had never asked to see the data, but that as a scientific collaborator, he was familiar with the databases’ contents.

In that Chatham House briefing, Daszak referred to the data as an “Excel spreadsheet,” a characterization that the Paris group says minimizes the amount of data that has gone missing. In reality, the group wrote in their letter, there were 16 databases with 600 gigabytes of data. This information came to light when DRASTIC was provided with archived logs containing descriptions of the database contents (though not the actual data itself). According to those logs, the missing databases contain records for 22,000 samples, mostly from bats, and sequences for at least 500 recently discovered bat coronaviruses.

Among those coronaviruses, according to a document prepared by DRASTIC, 50 are SARS-related and 19 at a minimum were grown in culture. In addition, according to the document, the log notes refer to a subset of viral sequences that “cannot be published” and “we have no idea what they are,” Demaneuf says. According to the DRASTIC document, the log notes, which were translated from Chinese, state that users can only access the unpublishable data by “contacting the relevant management personnel.”

Demaneuf says he’s unpersuaded by Daszak’s assertion that hacking threats justify keeping the databases under wraps. “Come on, this is nonsense,” he says.

“The Chinese have good technology,” he continues. Someone could even put the data on a $200 hard drive, he suggests, and pass it along. Daszak “should be saying ‘We worked together, show a bit of respect. Open your databases.’ But he’s not doing that.”

Undark reached out to numerous scientists who worked with Daszak, and most never responded. W. Ian Lipkin, an epidemiologist and professor of neurology and pathology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, in New York, has collaborated extensively with Daszak, and would say only that he is “an excellent scientist.” Similarly, Linda Saif, a virologist and mucosal immunologist at The Ohio State University, described Daszak and his EcoHealth colleagues on email as “a major contributor” to the field of bat coronavirus research.

Perlman speculates that scientists might be reluctant to grant press interviews “because the pandemic has been so wearing and the controversy is going on and on.” Opinions on the matter are strongly fixed, Perlman added, and scientists worry about having their comments distorted. Colleagues have been threatened, he says, and some friends won’t answer even benign emails or questions from reporters.

So far, Metzl says the letter demanding Daszak’s removal from the EcoHealth presidency has been met with silence. Daszak has been known to block critics on Twitter, a move that “makes it impossible to have the kind of interaction that we believe is necessary,” Metzl says. Because much of EcoHealth’s funding comes from government grants, “there must be a higher level of accountability,” he adds.

The WHO is now organizing a new team to investigate Covid’s origins, and while Daszak will not participate in the effort, members of the Paris group were initially critical of the investigative team’s shortlist, which includes several scientists who have publicly dismissed the possibility of a lab leak. The proposed panel has since been broadened to include two additional scientists “who can credibly bring additional perspectives,” says Metzl.

“It’s a step in the right direction,” he says.

Charles Schmidt is a recipient of the National Association of Science Writers’ Science in Society Journalism Award. His work has appeared in Science, Nature Biotechnology, Scientific American, Discover Magazine, and The Washington Post, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

C-SPAN has video of Peter Daszak in 2016 talking about inserting spike proteins into viruses to make them bond to human cells.

Pandemics – February 23, 2016 (C-SPAN website)

User Clip: Peter Daszak Describes His ‘Colleagues In China’ Manipulating Viruses (C-SPAN Website)

Pseudo-particles (pseudoviruses) are non-replicating particles containing just several viral proteins, not genome. They are often used to study various aspects of viral pathobiology as they are completely safe during manipulations.

All scientist are bias. How about Fort Detrick

Great article but you are being too kind to the man. He should be detained at Gitmo and interrogated.

He who is without sin, let him cast tje first stone.

I’m confused Tim. Are you saying it is ok to compare unleashing a catastrophe on humankind to telling a white lie.

Unbelievably good reporting. Neither accepting what is spoon fed nor buying into shallow conspiracy theories. Just exceptional.