Wanted by Monsanto: A ‘Journalist’

Who is a journalist? Could it be someone who works for the agrochemical and biotech giant Monsanto? The Missouri-based company currently has a job opening for what it’s calling a “Corporate Web Journalist,” whose duties would include “helping multiple stakeholders understand and advocate for modern agriculture.”

The title notwithstanding, everything else in the job description seems to call for a marketing or communications specialist whose core responsibilities amount to writing and producing informational material about the company and its business interests — presumably in a manner that reflects well on Monsanto. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, and it surely offers better pay than the average newspaper. But would the successful candidate really be taking a job as journalist? Again, who is a journalist?

It’s a question that has long dogged the profession (such that it can be defined) and animated the courts — and it’s one that has become only more complex in the digital age. The advent of blogging, for example, eventually gave rise to intense legal haggling over whether or not independent bloggers are journalists. That might seem like a naïve and somewhat trite question in 2017, but it was only a few years ago that a defamation case wrestled with this very question.

“The protections of the First Amendment do not turn on whether the defendant was a trained journalist, formally affiliated with traditional news entities, engaged in conflict-of-interest disclosure, went beyond just assembling others’ writings, or tried to get both sides of a story,” Ninth District Court Judge Andrew Hurwitz wrote in 2014 in deciding that case.

In other words, the courts have traditionally demurred when it comes to defining who is a journalist and who is not, and for the most part, this has worked well. Complications and confusion may be inevitable when anyone is technically a journalist, simply by virtue of saying so, but the alternative is a slippery slope. “Once a ‘journalist’ is defined, then before long the government might start raising the idea of licensing journalists,” the Society of Professional Journalists notes, “which can lead to a form of censorship that is found in other countries.”

And so the definition has remained loose — and grows ever looser. Today, organizations like The Gateway Pundit enjoy White House press access alongside The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Last month, The Washington Post reported that the pool reporter assigned to cover Vice President Pence — “that is, the reporter who supplied details about Pence’s daily activities as proxy for the rest of the press corps — was an employee of the Heritage Foundation, the conservative think tank.”

Are all of these folks journalists? That’s a question that will divide many Americans as surely as the presidency of Donald J. Trump itself.

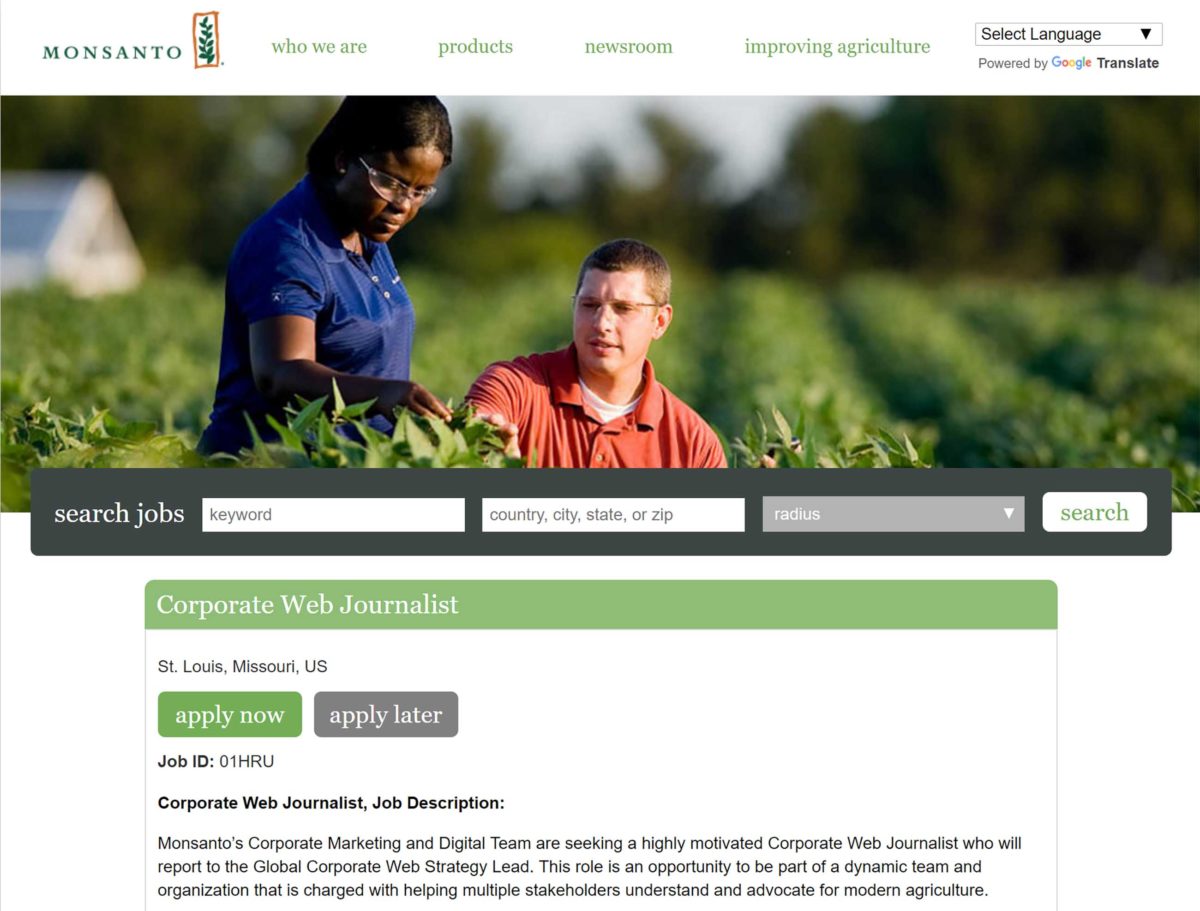

A screen shot of part of Monsanto’s ad for a “Corporate Web Journalist.”

But how about a journalist for Monsanto? What sorts of questions would he or she ask the commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, or representatives of the U.S. Department of Agriculture? If scientists with the Environmental Protection Agency raised concerns about the impact of one of Monsanto’s agricultural chemical products on public health, would the company’s journalist report it? What if the concern was over the product of a competitor?

These are fanciful questions, of course, and there’s no indication that reporters from Monsanto will be granted seats among the White House press corps anytime soon. At the same time, many things that have come to pass seemed downright impossible just a few short months ago — and with the proliferation of so-called “fake news” effectively blunting the power of the press as we’ve known it, it seems worthwhile to consider what the word “journalist” really means in the modern age — and particularly as it relates to science coverage. So much of our modern democracy, after all, hinges on the dispassionate investigation and unpacking of complex and technical information, from climate change and childhood vaccinations to genetically modified foods.

Journalists, we like to think, are on the case. But which ones? Which ones are honestly pursuing truth and accountability, and which ones are marketing a political agenda, or a product? A quick search suggests that “journalist” positions are currently available with a wide array of organizations, from the National Safety Council and Virginia Tech to Major League Soccer. The California-based cereal company Kahsi is on the hunt for something called a “Brand Journalist.”

Does any of this matter? Maybe not. Maybe it’s better to focus, as groups like SPJ do, on identifying acts of “journalism,” rather than splitting hairs over defining who is, and who isn’t, a “journalist.” Then again, what’s to suggest that the average reader makes either distinction?

As it stands, a representative for Monsanto suggested that its job listing was more illustrative than anything else: “It’s my understanding that for this position, ‘Corporate Web Journalist’ is being used as it embodies the mindset of the type of person and voice we’re looking for,” wrote Monsanto spokesman Billy Brennan in an email message, “someone who can identify opportunities and tell articulate and engaging stories on various company channels in a timely manner.”

“This is so that we get the right type of applicants,” Brennan added, “and it may or may not end up being that person’s actual job title.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Anyone who follows GMOs and agrichemical toxins knows what Monsanto “journalists” do.

Monsanto has many of them out there flogging their dangerous products.

They often do not acknowledge who they are.

There are 2 comments by that sort here already.

Why shouldn’t they ask for someone with that skill set? USRTK got Carey Gillam from Reuters. Food and Water Watch has that guy who shows up to shout at the National Academy, Tim Schwab. Nobody batted eyelashes when they went to those organizations–with the clear mission to influence media coverage and often do the stories themselves, which get published in mainstream places.

The question raised here is not whether Monsanto (or any other company or group) ought to hire dogged communications specialists, Mary. Of course they should. The question is whether or not that person ought to be called a “journalist.” Given that the term has no legal definition, Monsanto can certainly call their comms staff “journalists” if they like, but it’s worth considering whether that further erodes the Fourth Estate in any way. I personally think it does, though I’m not sure I’d want use of the term officially policed in any way either.

Really–the title is the problem? Not the fact that journos are acting as agenda hacks at activist groups, attacking public scientists? Using their jouno cred to get bylines at media sites?

I do think your ire is misplaced.

No ire here, Mary. Just a good-faith discussion. Let’s keep it that way.

They are engaged in propaganda along the lines of Eddie Bernays. They’re running a huge propaganda campaign. It stinks to high heaven and they’re full of lies. They cannot be trusted. The tripe in one comment about how “ethical” they are is more PR. They are a lying, criminal company using propaganda to pull the wool over everyone’s eyes.

I used to work for Monsanto and it is amazing how ethical they are. The complete opposite of what is portrayed by the green movement. Every employee takes courses of ethics and how to follow their guidelines to not violate the laws and treat people fairly. Safety is number one for themselves and their customers and the public. In 17 years of working for them I never heard any time when if there was a safety issue with product that they would cut corners or do the wrong thing. They usually went out of their way to not develop product if there was a int of any harm that could come. There is a 1800 hot line to a separate ethics team that reports directly to the board so any question or concerns you have can be addressed. here ohs a simple example of good business practices. If a competitor employee happens to talk with you at a conference and starts to mention possibly confidential information to his employee you would need to stop him/her and also inform your company that you might have heard something inappropriate so that the company couldn’t take advantage of it. I have sat in many meeting where regulatory safety studies were discussed and never was there a hint that the company would sweep something under the rug or hide pertinent information from regulators. The reason for this ethics is fairly simple – any company that lies to regulators is not only unethical but it is criminally breaking the law. Safety studies are signed by employees as being correct and accurate to the best of their ability under penalty of perjury. When has any ant-GM or anti-Monsanto group ever had to live to that standard.

The really bad thing about all this anti-Monsanto stuff is not the effect on their business since they make effective products that are needed by farmers – it is that the public is distracted from real safety issues in food and the environment.

Here is a perfect example of how the activists are misinforming the public – the UN, US EPA, EU EPA equivalent say glyphosate is not a carcinogen – the EU spent 4 years styling the data. The WHO has 4 parts that formed an opinion and 3 said it is fine and the fourth took 4 hours and put glyphosate into the same hazard category – probably carcinogen – as processed meats, working in a beauty salon or working nights but somehow this makes glyphosate more hazardous that alcohol – a known carcinogen and are they saying ban processed meats?

The fact is no chemical is safe – glyphosate is probably the least hazardous herbicide and less toxic than table salt but now people misinformed by the media will switch to be more harmful pesticides – that is a crime!

Please. Ethical. Let’s talk about Roundup. Glyphosate’s carcinogenic potential has been known to Monsanto and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) from long term animal experiments since the early 1980s, but the company has repeatedly dismissed such claims and refused to disclose the studies, buy claiming they contain “trade secrets”. They only did testing on the one active ingredient — glyphosate. While it may not be toxic enough to make you immediately drop dead from ingesting it, the chronic effects are horrendous, and we are now finding it to be a ubiquitous as PCBs in the environment (another Monsanto product that they lied about — let’s talk ethics). So NO testing was every done on the final formulation product, with adjuvants making it 1000 times more toxic, in fact one of the most toxic herbicides on the planet. Monsanto has been caught time after time lying and distorting the truth. It is common knowledge. Please don’t insult the intelligence of the readers here thinking anyone will believe you. There is lots of information on our website, momsacrossamerica.org/data. Please don’t every mention Monsanto and ethical in the same sentence ever again.