Of Rumors and Tremors

What appeared to be a carbon monoxide cloud over the West Coast turned out to be a computer glitch. And no, it doesn’t signal an earthquake.

No biblical foresight needed: To find out when the next big natural disaster will hit, look no further than the Internet.

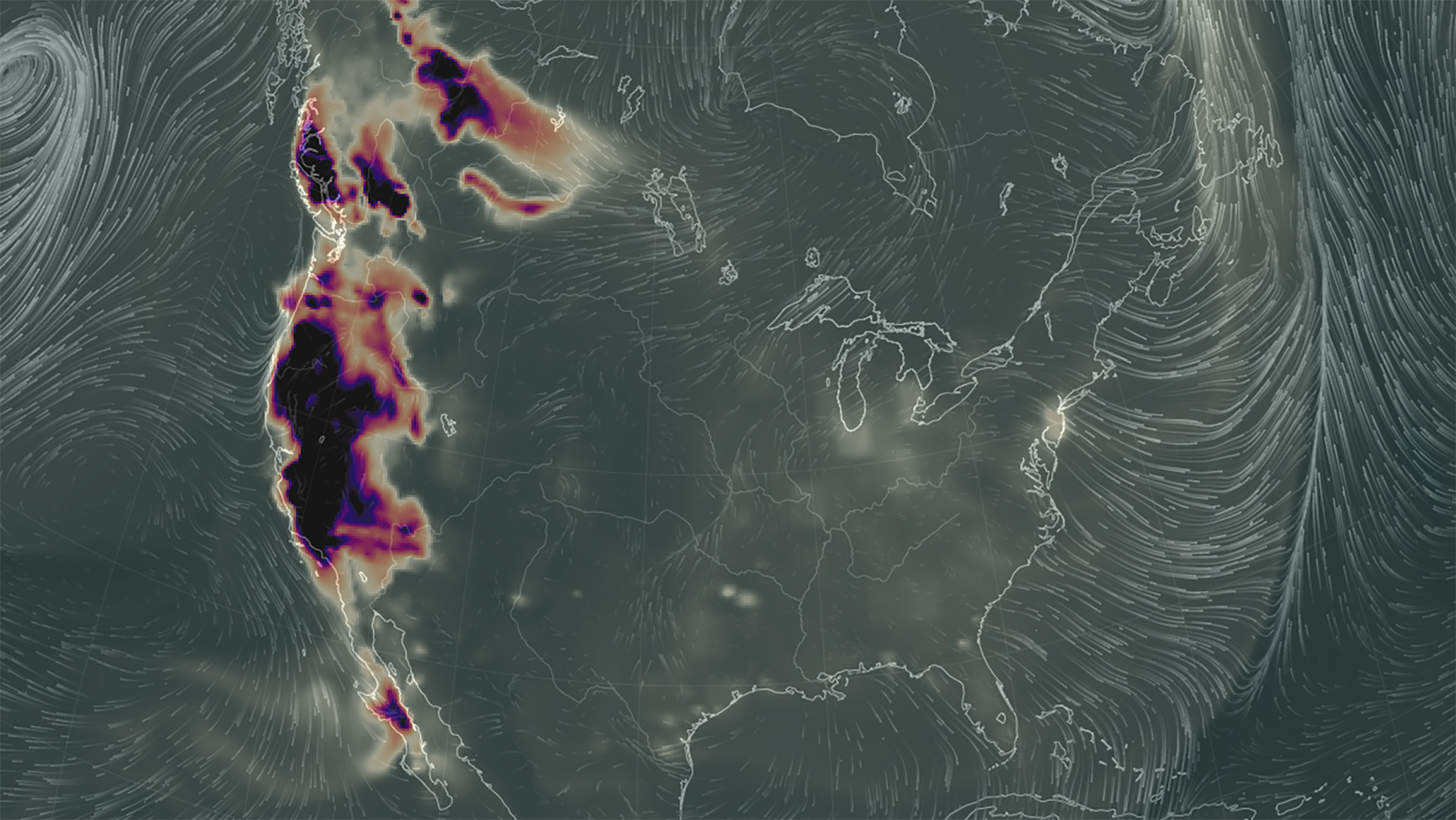

Late last month, the epicenter of the web’s frequent doomsday rumors focused on what appeared, on a satellite data-sourcing website, to be a cloud of carbon monoxide over California. The image was widely circulated on social media, often alongside claims that the apparent gas cloud heralded a looming West Coast earthquake — speculation that was fueled in part by a single 2010 paper published in the journal Applied Geochemistry suggesting that CO releases might be an earthquake precursor.

Of course, the earthquake never happened — and according to NASA, neither did the gas release that spurred rumors in the first place. The image, the agency said in a public statement issued on March 1, arose from an instrument glitch. Experts also quickly pointed out that there is no clear link between carbon monoxide releases and subsequent earthquakes.

“These predictions usually start with people who look for surprising things on the Internet and then interpret them their own way — and usually ignore everyone who disagrees,” said John Vidale, a seismologist at the University of Washington and the director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network.

Such rumors might be seen as a byproduct of how accessible science has become through the Internet. The web makes a glut of scientific data and published papers available to the public, but it does not guarantee they’ll be interpreted correctly.

Such was the case with the 2010 Applied Geochemistry paper. Authored by Ramesh Singh, a professor of physics at Chapman University in California, the paper paired a detectable carbon monoxide release with a rise in the water table prior to a 2001 earthquake in India. It was a loose association, and Singh and his co-authors provided no conclusive evidence that carbon monoxide might be an earthquake early-warning system — something that researchers have been chasing for decades.

The seismological community, for its part, remains skeptical of theories linking precursor gas releases to earthquakes, which recently resurfaced in relation to a 2009 earthquake in L’Aquila, Italy. And even Singh suggested that denizens of the Internet were overstating his research.

“There is no scientific understanding that all earthquakes are going to give off carbon monoxide,” Singh explained in a phone call. “People should not get panicked, because a release of carbon monoxide could be caused by so many things.”

Yet panic, in some form, continues. Despite NASA’s clarifications of the satellite glitch, rumors persist that a quake is coming, as do conspiratorial claims that NASA’s explanation is a cover-up.

This doesn’t surprise Vidale. In early January, a glitch in a seafloor pressure sensor off the coast of Oregon caused a gap in data recorded between high and low tide — interpreted by some as evidence the seafloor had dropped by a meter due to seismic activity. When the National Weather Service posted an explanation of the gap, social media users still accused the agency of trying to hide an impending quake.

Vidale compares the web’s active conspiracy network to those who believed “articles about aliens in the backyard in the National Enquirer.” Even so, this alarmism does not come without repercussions.

“Almost everyone who believes these theories, every week they’ve gotten scared of something or other,” Vidale said. “People post about how they’ve spent the last of their money on emergency supplies, or pulled kids out of school, after reading these posts.”

Perhaps the greatest danger of these rumors is that they obscure the lack of warning that usually precedes an earthquake. Government earthquake warning systems are highly sensitive, yet they give little more than a few minutes or a few seconds for people in the affected area to react — time that can only save lives if residents have an earthquake plan prepared ahead of time.

“People should take the logical steps to prepare,” said Vidale, “not building a bunker in the basement.”

He added that despite the potential for misinterpretation, the social media age remains a boon for scientists seeking to communicate with the wider world.

“Overall, scientists are getting more information out on social media than we used to, and it’s a very flexible, powerful way to do it,” he said. “But there are these side effects.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Need more information about the glitch and what it actually measured. Something is clearly being recorded here. What is it? Water vapor?