In the Battle Over Lead Ammunition, Science Collides With Culture

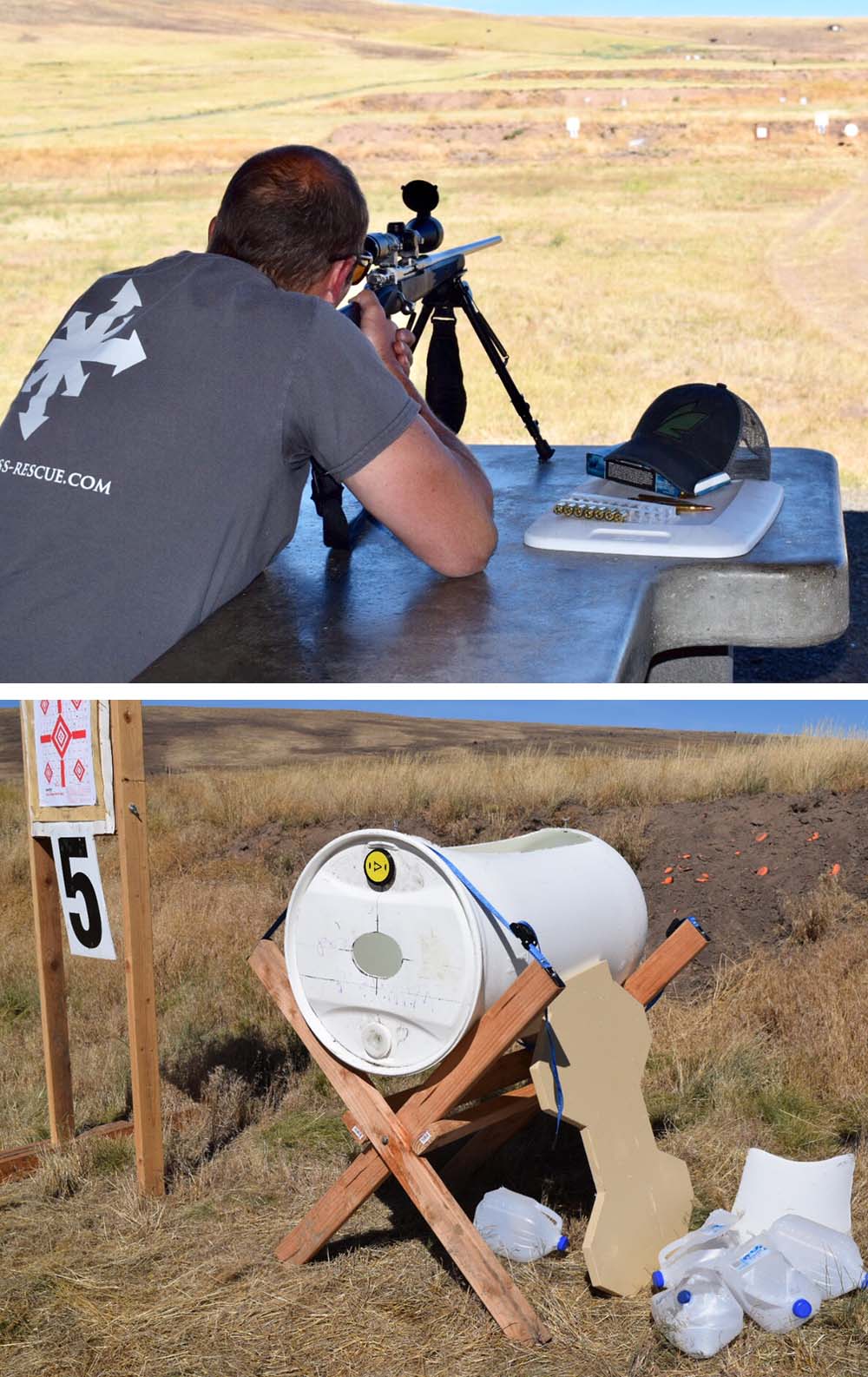

“Eyes and ears,” Leland Brown calls out. “We’re going hot!” We pull on our safety glasses and earmuffs, though neither prevents the concussive blast to our chests as Jeff Yanke pulls the trigger of his Ruger M77 rifle, sending a bullet coursing towards the back end of a 50-gallon rain barrel.

The white plastic drum, flanked by a menagerie of more traditional steel targets depicting a coyote, a chicken, and a pig, rests horizontally on a wooden cradle 100 yards downrange. A round hole is cut into its bottom, which faces Yanke, and inside the barrel are five plastic, one-gallon jugs. Each jug is filled with water and arranged in a line, front to back, ready to absorb the incoming round — a crude but effective enough proxy for the dense hide of a game animal.

Target practice: Above, Jeff Yanke, a hunter and wildlife biologist, takes aim at test targets downrange (below). The barrels are loaded with one-gallon jugs filled with water to absorb the incoming round.

Visual: Lynne Peeples

Yanke reloads and resights his rifle, then fires a second bullet into the hole at the bottom of a neighboring barrel. Another puff of gunpowder fills the air, and the experiment is over.

With assurance that the range is now “cold,” we drop our protective gear and step out from under the range’s shaded firing line into the mid-August sun. The Blue Mountains rise to the right, just beyond the earthen mound backstopping the targets. We hike towards the barrels and, reaching the first, Brown’s team begins extracting twisted and torn water jugs. All five are destroyed, and Yanke eventually retrieves the blunted piece of metal responsible for their demise.

“This is textbook,” says Brown, a biologist and non-lead hunting education coordinator with the Oregon Zoo. He’s here at the Eagle Cap Shooters Association in Enterprise, Oregon to demonstrate the differences between ammunition made of lead and those made from other materials. He nods through his trimmed beard to the spent ammunition that Yanke, a member here and a biologist with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, now holds in his hand — and to the remnants of water jugs strewn on the ground. The point of the bullet is split and splayed like flower petals, but it remains mostly intact.

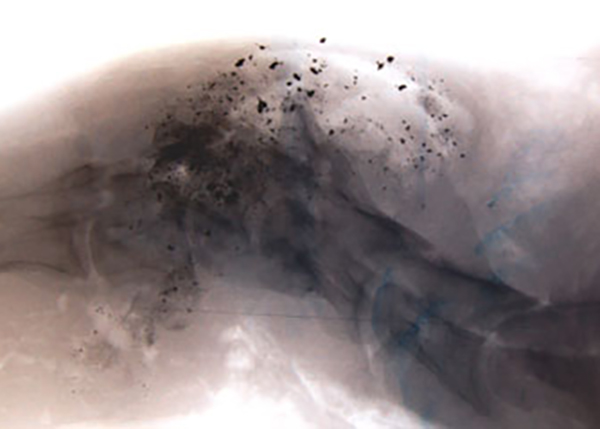

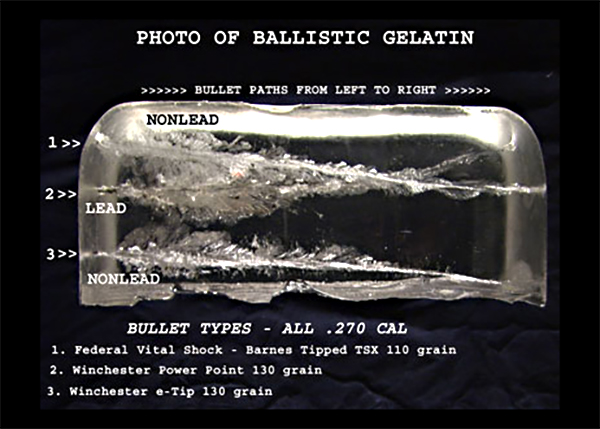

In the other barrel, the men find a vastly different scenario. Only two of the five jugs have been fully penetrated by the bullet, which has broken into fragments that now litter the inside of the barrel. The largest remnant of the spent slug resembles a sautéed mushroom, and a scale confirms what is visibly apparent: While the first bullet, made entirely of copper, retained 99 percent of its original weight, the second bullet, comprised of lead, broke into pieces, losing a quarter of its weight when it hit the jugs. “We never discuss what happens to the other 20 to 30 percent of the lead bullet,” says Brown. “Where does that end up?”

Yanke proposes an answer: “That shit was in my cheeseburger last night.”

Whether any particles of lead — a well-known neurotoxin when ingested in sufficient quantities — actually tainted Yanke’s elk burger is impossible to know. Some scientific studies do point to a chance of contamination when wild game is taken with lead ammunition, and Yanke did take down an elk last hunting season with a lead bullet. As hunters do, he’d also left a portion of the animal’s innards behind in the field.

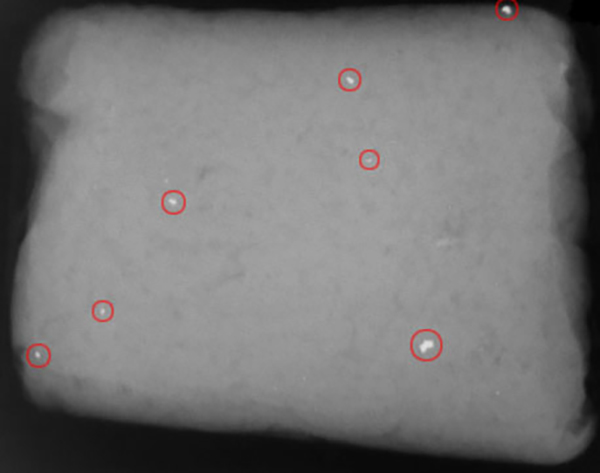

What’s clear is that previous field analyses have shown that hundreds of lead fragments — one study counted a total of 738 — can extend as far as 18 inches from a lead bullet’s path through an animal, well outside the range where hunters typically trim. Scientists have also warned that lead in those discarded gut piles can poison eagles and other wildlife that seek them out for food — but the concerns surrounding lead ammunition aren’t limited to hunting. Lead bullets used in target shooting by military personnel, law enforcement officers, and the public, has been found to pollute soil and water around some outdoor shooting ranges, as well as the air and surfaces of indoor ranges when not properly cleaned or ventilated.

The continued use of lead in ammunition, environmental and public health advocates say, remains an under-appreciated and preventable source of exposure to the toxic heavy metal for millions of Americans. They argue that the evidence of real and negative impacts is so overwhelming, in fact, that the lack of more aggressive regulation borders on the absurd, if not downright negligent. “A good bullet should not kill twice,” said Carrol Henderson, a hunter and an educator with the Department of Natural Resources in Minnesota.

Indeed, despite substantial scientific evidence linking the use of lead ammunition to a host of environmental and public health threats, roughly 90 percent of the 10 billion rounds purchased every year in the United States still contain lead. Until recently, the only federal regulation regarding lead ammunition requires lead-free shotgun pellets for the hunting of waterfowl. That changed on the final day of Barack Obama’s presidential term, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a decree that would phase out the use of lead ammunition (and some fishing tackle) on federal lands. The last-minute move was immediately blasted by the firearms and shooting sports industries, which hope to see the decree quickly overturned under the presidency of Donald J. Trump. Given Trump’s courtship of both industries during his campaign, it seems likely they will get their wish.

At the state level, meanwhile, roughly 30 states have implemented, and more are currently considering, additional lead ammunition restrictions — including a fiercely debated measure in Henderson’s state, which would prohibit the use of lead ammunition for bird hunting on state lands.

But public health advocates like Dr. Michael Kosnett, an environmental toxicologist at the University of Colorado, Denver, suggest that these halting measures are nowhere near enough. Kosnett was among 30 doctors and scientists who co-authored a consensus statement in 2013 on the health risks of lead-based ammunition. “We still drive cars. We still paint houses,” Kosnett told me, referring to the removal of lead from gasoline and house paint in the U.S. during the 1970s. “There are substitutes for lead in ammunition, too. If there’s a feasible way to avoid the risk by product substitution, then why not do that?”

The answers to that question are complex in their details, but simple enough from the broadest view: As with other public health and environmental threats, from smoking to climate change, many people remain unconvinced that risks from lead ammunition are real — and the firearms industry has played an outsized role in sowing doubt about the science. The greater threat, they argue, is to Americans’ freedom to hunt and own firearms, and the industry spends lavishly to peddle this viewpoint.

When debate over a state ban on lead ammunition heated up in California, for example, the firearms industry upped its spending, and founded the non-profit Hunt for Truth Association.

“[G]roups attempting to ban the use of lead ammunition base their claims on faulty science,” a coalition of firearm industry partners, including the National Rifle Association and the National Shooting Sports Foundation, declares at HuntForTruth.org, an industry-supported website. The site assiduously catalogs — and seeks to debunk — many of the key scientific arguments against the continued use of lead bullets, calling into question researchers’ methodologies and their own inherent biases. The Hunt for Truth Association, which publishes the website, says that its members will “remain vigilant in their desire to maintain the use of lead ammunition while continuing to preserve America’s ‘traditional hunting heritage.’”

Among other criticisms, the NSSF — the gun industry’s largest trade group — maintains that copper and other alternative ammunition simply performs poorly compared to lead, which the group prefers to call “traditional ammunition.” It also carries a higher price tag — and these differences, lead-ammo advocates say, could prove to be very costly to conservation. After all, if non-lead bullets cost more but are less effective, fewer people will ultimately choose to hunt, the NSSF says — and that would result in fewer dollars spent on firearms, ammunition, and, most importantly, licenses and tag fees, a portion of which funds projects to protect the environment and wildlife.

“It’s actually the animals that groups supporting a ban purport to want to help that would be the ones who suffer the most,” said Lawrence Keane, senior vice president of the NSSF.

Given the broad influence of industry and the entrenched views it cultivates, it’s little wonder that confusion and distrust permeate groups of hunters and others who fire guns at Eagle Cap. Bob Jones, an active member who hosts big-bore matches at the range, admitted some initial worries when he agreed to the demonstration on that sunny Saturday, during which Brown allowed local hunters to freely test out an assortment of copper ammunition in their rifles. It was the first time anyone had fired copper on his range.

“Guys here fear their guns are going to be taken away,” says Jones. “I didn’t know how they’d like it.”

Six hundred miles southeast of Enterprise, antler archways decorate the four corners of the town square in Jackson, Wyoming. To say hunting is popular here would be a sublime understatement. Native Americans frequented the local valley, today known as Jackson Hole, centuries ago to hunt large game. Europeans and Americans later followed, and it remains a top tourist attraction today.

Until recently, just about every bullet fired into a buffalo, deer or elk here was made of lead.

The origins of lead ammunition date back thousands of years, to well before guns themselves. The Greeks and Romans shot lead balls from slingshots. Widely available, soft and malleable, lead continued to be the easy choice when people began forming musket balls. And as firearm technology evolved, so did the shape of bullets, some eventually stretching into the streamlined projectiles that now spin out of rifle barrels. Then, with the discovery that these lead bullets tended to leave traces of themselves inside the rifle after each firing, metal jackets arrived. Variations of jacketed ammunition — typically a harder metal such as copper encasing a soft lead core — are among the most popular bullets used today.

Those same Greeks who made some of the first lead ammunition may have also been the first to recognize the heavy metal as toxic. In 250 BC, Greek philosopher Nikander of Colophon reported on colic and anemia that resulted from lead poisoning. The anecdotal evidence would mount — Benjamin Franklin contributed in the 1700s by noting lead’s “mischievous” effects on workers — and eventually turn to more concrete science in the late 19th century. Still, it took until the latter half of the 20th century before the U.S. government began to heed the warnings with a phase-out of lead from gasoline, plumbing and most paints. Lingering lead in old pipes and peeling paint still poses profound health risks, of course, as demonstrated recently in Flint, Michigan.

The dangers of lead have been known, or at least suspected, for centuries, but it took until the latter half of the 20th century before the metal was phased out of many common materials and products. Ammunition, however, remains predominantly lead.

Visual: EPA

Meanwhile, lead used in ammunition has largely escaped serious scrutiny. “The vast majority of people don’t even know about it or think it’s an issue,” says Bryan Bedrosian, a senior avian ecologist at the Teton Raptor Center in Wilson, just outside of Jackson. “But once you learn about it, it makes sense. Of course you shouldn’t be using lead.”

At a picnic table next to a red barn where center staff cares for sick and injured raptors, Bedrosian describes his research on the impacts of lead ammunition on birds of prey. In 2004, while working at Craighead Beringia South, a wildlife research and education institute in nearby Kelly, Wyoming, he’d started collecting blood samples from ravens. Nearly half of those he tested during hunting season had lead levels above 10 micrograms per deciliter, while just 2 percent had similarly elevated levels in the off-season. (For reference, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now considers a child lead-poisoned if his or her blood lead level reaches or exceeds 5 micrograms per deciliter.)

“At the start of hunting season we saw a spike everywhere. You couldn’t make up data any better if you wanted to,” says Bedrosian, who is wearing a t-shirt with an image of an owl, another raptor.

Bedrosian moved on to eagles a few years later and uncovered the same “super clear picture,” he says. Nearly a quarter of eagles his team tested during hunting seasons had lead levels above 60 micrograms per deciliter, while no blood samples from birds surpassed that threshold during the non-hunting seasons.

These seasonal connections, coupled with counting hundreds of visible lead fragments in x-rays of gut piles, convinced Bedrosian to do something. With funding from environmental groups like 1% for the Tetons, he helped launch a program to provide free and discounted copper ammunition to local hunters. The effort seemed to pay off. “The more hunters that used copper bullets,” recalls Bedrosian, “the less lead we found in eagles.”

Weakness, lethargy, weight loss, a drooping head and tattered wings are among the recognizable signs of lead poisoning in an eagle, says Meghan Warren, the rehabilitation and volunteer coordinator at the center, sitting next to Bedrosian at the picnic table. “They act really depressed,” she adds. “The tips of their wings might be coated in green goop from diarrhea that dribbles out. It’s really terrible.” The two note having seen blood lead levels as high as 728 micrograms per deciliter in birds brought to the center.

Still, identifying lead poisoning in a wild animal is not always so straightforward. The effects can be hidden, indirect and subtle. Birds don’t go to the hospital when they’re feeling sick. And finding a dead one is rare. “If they are not scavenged upon, a bird tends to find a quiet, dark place to hide and die,” says Bedrosian.

Warren notes that birds will often arrive at the center, not with obvious symptoms of poisoning, but with injuries that may have resulted from a lead-induced lack of coordination. They might run into a wind turbine, a power line or a car. “Or maybe they’re not coordinated enough to catch fish and starve,” adds Bedrosian. “What comes in as the proximate cause is not necessarily the ultimate cause.”

Even more subtly, lead exposure may trigger an “artificial selection process” in birds, explained Julia Ponder, executive director of The Raptor Center at the University of Minnesota. Survival of the fittest could be reversed, since the fittest birds — who would typically be the strongest breeders — also tend to be the first to feed on a gut pile.

The NSSF takes issue with the methodology used in the majority of studies on the topic, stating that most researchers test and extrapolate from raptors found dead or treated in a rehabilitation center. (Of note, Bedrosian’s research with eagles focused on wild, free-flying birds.) The gun group prefers the findings of a 2014 master’s thesis out of Iowa State University, in which a student tested lead levels in fecal samples taken from nesting bald eagles and reported that few birds appeared to have been exposed to “high levels of lead.”

“The Iowa study finally takes a meaningful look at the anti-hunting groups’ argument that traditional ammunition poses a threat to populations,” the NSSF said in a statement.

That thesis has resulted in one peer-reviewed study, which looked at lead levels measured in the feces and blood of birds at a rehabilitation center and concluded that the feces test, which is non-invasive, could be a valuable research tool. The follow-up study did not, however, discuss the conclusions and interpretations from the Iowa master’s thesis that are underscored by the NSSF — findings that both Ponder and Bedrosian suggested were of little surprise, given that the student’s samples were taken outside of hunting season, and from birds healthy enough to nest.

Steve Merchant, wildlife population and regulation program manager with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, conceded the NSSF’s point that no one can definitively say whether any species would be more abundant if lead ammunition was banned. But such a lack of proof comes with the territory in science: An absence of evidence, as scientists say, does not prove evidence of absence. “Have we experimentally designed a study where lead ammunition is banned in half the state and not the other half, and then found populations growing in the area we’ve banned lead? No,” he said, noting such a study is not feasible. “But there is certainly a wide body of evidence that shows that birds at an individual level are dying because of the ingestion of this.”

The firearms industry frequently raises another point: Lead fragments in game meat are in a “metallic form” and are, therefore, less toxic than other sources of lead. Advocates again call this misleading. “Metallic lead, in a bullet or piece of bullet fragment, is not at that point toxic,” said Vernon Thomas, a professor emeritus at the University of Guelph in Ontario, who’s written widely on the topic. “It only becomes toxic when solubilized and absorbed in the blood of an animal.”

“There is a lot of misinformation out there,” added Merchant. “The calls that there is no science are not coming from the scientific community.”

Minnesota, again, is among a number of jurisdictions looking to go further than the 1991 federal waterfowl rule. Due in part to the work of Bedrosian, Grand Teton National Park now bans lead ammunition for hunting elk within its boundaries. And in responding to challenges in the recovery of the endangered California condor, for which lead has been deemed the leading cause of death, Arizona and California have implemented voluntary and mandatory bans, respectively. By July 1, 2019, non-lead ammunition will be required for all hunting in California.

NSSF’s Keane criticized the California move as being driven by “anti-hunting” groups and lacking in “sound science demonstrating that there was a population impact caused by use of traditional ammunition.” While the group acknowledges that some sick condors have been found with elevated blood lead levels, they reject claims that lead ammunition deserves any broad blame. In at least one case, they point out, condors were observed eating lead paint chips off an old fire tower. The group is also critical of isotope studies that have traced lead detected in condors to the type of lead used in ammunition. The last primary lead smelting plant in the U.S. closed its doors in 2013, leaving recycled lead the form most often used by ammunition makers. What a hunter shoots into a deer today may well have been in his truck battery last year. And that fact, the NSSF notes, could have skewed study results.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service acknowledged that there are multiple sources of lead in the environment in its review of the issue published in 2016. Still, the service cited “numerous lines of evidence” — from the recovery of ingested lead fragments from exposed birds, to observations of birds feeding on contaminated carcasses and increased death rates during hunting seasons — in its conclusion that spent lead ammunition is the “most frequent cause of lead exposure and poisoning in scavenging birds.”

Christine Kreuder Johnson, a professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine authored a separate review of the topic in 2014. She suggested we know more than enough about the threats to scavenging birds from lead ammunition to be taking action — and not just for the birds’ sake. “Lead affects all species in the same way,” she said. “Wildlife in general is going to be very heavily exposed to the same things people are exposed to. When we finally detect problems in wildlife, we really need to pay attention.”

It was a conversation with Bedrosian shortly after the birth of his daughter, Avery, which convinced Kevin Taylor to switch from lead to copper in his rifle. “To knowingly feed her elk meat that has the potential to contain lead fragments is an absolute no brainer,” says Taylor.

Up a steep and windy gravel road a few miles from the raptor center, I find Taylor, a botanist and wildlife expedition guide in Jackson, Wyoming, erecting a new fence to protect his chickens from predators. Like Yanke, nearly all of the meat Taylor’s family consumes comes from the one elk he takes every fall, not far from their home perched near the Tetons. And they eat just about every part of the elk — edible internal organs and all. “That’s our protein source,” he says, his blue eyes piercing out from between his tan hat and bushy red beard. “Well, in addition to the eggs from our chickens.”

Lead exposure from wild game is a real risk. A study of North Dakotans, published in 2009 by the CDC and the North Dakota Department of Health, found that as wild game consumption increased, so did blood lead levels. The authors wrote that their findings had important implications for hunters and their families, as well as low-income families. (Sportsmen Against Hunger and other programs donate game meat to local food pantries.) The NSSF, however, categorized the research as among “plenty of junk studies that make headlines.” They noted that the difference in blood lead levels between participants who ate wild game harvested with traditional ammunition and non-hunters, after adjusting for other factors such as exposure to house paint, was a mere 0.3 micrograms per deciliter. “There is certainly no evidence at all that there is a risk to human health by consuming game harvested with traditional ammunition,” said Keane.

Because the study was conducted four to five months after hunting season and included few children, who tend to absorb more lead than adults, the study authors suggested that the results might downplay the true extent of exposure. The study did find that more recent consumption of wild game — and greater consumption of wild game — led to higher blood lead levels. And while the average blood lead level in the exposed group was relatively low at 1.27 micrograms per deciliter, the authors noted that it was still “orders of magnitude higher than the levels of preindustrial human societies.”

The CDC has warned that there is no safe level of lead in the blood of children. And, as in animals, the effects of lead on people may range from subtle to severe. Exposure even under the current CDC reference level of 5 micrograms per deciliter, studies say, may leave a developing child a little slower to learn, a little shorter of attention, a little less successful on tests and at work, and a little more likely to engage in criminal activity. (Recent reports suggest the agency is now considering further lowering this threshold to 3.5 micrograms per deciliter.)

Adults are also far from immune to lead and its health effects. Studies hint that chronic blood lead levels as low as 2 micrograms per deciliter may increase the risk of death from a heart attack or stroke. Evidence is also emerging of lead’s role in reproductive disorders, kidney disease, cognitive decline and neurological problems. Lead is damaging, in part, because it mimics the calcium essential in maintaining healthy bones, nerve cells and blood pressure. More than 90 percent of lead in adults is stored in bones, where the metal’s trickery has helped it claim spots generally reserved for calcium. And that squatting lead is prone to leaching out at inopportune times. It can, for example, take the same ride into the womb as the calcium naturally released from a pregnant woman’s bones to nourish her growing fetus.

In addition to potential exposure from eating contaminated meat, workers and customers at a shooting range may inhale, ingest or absorb lead while loading ammunition, shooting, retrieving spent bullets and cleaning guns. The U.S. is home to more than 2,500 ranges and, every year, at least 20 million Americans participate in recreational shooting, according to the NSSF. Reports suggest the figure is increasing, with shooting growing in popularity among women and children.

Between 2001 and 2013, the number of women target shooters rose from 3.3 million to 5.4 million, according to the NSSF. Meanwhile, the firearms industry has targeted children in an effort to ensure the future of shooting sports, according to a 2013 analysis by The New York Times and a 2016 study by the Violence Policy Center. Some ranges even offer birthday party packages.

Depending on the type of gun used, the heavy metal can be released through the fragmentation or vaporization of the bullet and from the lead used as the primer or propellant. Experts agree that these risks can be controlled with proper ventilation along with personal precautions. After using an indoor or outdoor range, for example, workers and customers should wash their hands thoroughly with soap and cold water. (Warm water can actually open up the pores for more absorption of lead.) And when returning home from the range, they should immediately remove their shoes and clothing, and wash their hair.

Problem is, things can go — and have gone — wrong, with tragic consequences, as The Seattle Times highlighted in their series, Loaded with Lead. Sometimes range owners disregard certain rules and regulations. Other times, ignorance or simply bad luck is to blame for toxic exposures.

Health experts express great concern for members of the military and law enforcement, who probably spend more time than anyone at gun ranges. The U.S. Department of Defense stated that while it has fully converted 5.56-millimeter war reserve cartridges (fired from the M16 rifle) to lead-free, their training rounds remain a mix of lead and non-lead. “The U.S. Army operations office (G-3) is tracking that and ensuring there is a timeline and flow that allows us to transition as soon as feasible,” the DoD said in a statement.

The FBI also continues to use only lead bullets in its training, noted Kurt Crawford of the FBI Academy. In special situations, such as for a pregnant agent, the bureau does allow a reduced lead propellant.

Other range regulars at risk include the nation’s hundreds of thousands of police officers, noted Howard Mielke, an expert in lead poisoning at Tulane University School of Medicine. “I can just imagine that some of the people in law enforcement are really conscientious about making sure they are good at handling a firearm,” he said, suggesting this translates to a lot of time at the firing range. “And that could severely expose them to lead, to the point that it may trigger them to get very nervous — rather than relaxed and calm — in a setting where they feel threatened.” Studies published in 2009 and 2016 suggest that lead exposure from shooting may decrease verbal memory and increase the frequency of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

“Inhaling lead particles at a shooting range can raise a person’s blood lead levels very quickly,” added Mielke.

That’s just what happened to Amy Crawford. In 2008, while training as a law enforcement officer in Kirkland, Washington, the ventilation system at an indoor firing range failed. Her squad continued shooting. “I couldn’t see an arm’s length in front of me,” recalled Crawford. “But we were just using the haze like a tool. Like, if you can’t see in real life, how do you address the situation?”

Crawford and her colleagues had not been taught about lead and its dangers. They coughed and itched their eyes through the training, then woke up the next day with flu-like symptoms and a metallic taste in their mouths. When the officers went for testing, Crawford’s blood lead level came back the highest at 33 micrograms per deciliter.

While Crawford said she feels fine today, she worries about the future. “I don’t know what the repercussions are going to be,” she said. “Obviously, I’m worried about having children.”

The Kirkland Police Department recently opened a lead-free shooting range, the first of its kind in the state. And although she has since left the force, Crawford praised the move. “I do not want this to happen to anyone else,” she said. “It’s totally preventable.”

A similar rationale led Taylor to his decision to hunt with copper bullets, and to share what he’s learned about lead bullets with others. “One of my mantras is, ‘Control the things you can control in life,’” he said. “There are a lot of other things we can’t control.”

After introducing me to Butterscotch, Buttercup and the rest of his flock, Taylor leads me out of the chicken run and into his home. He pulls a bowl of homegrown raspberries out of his refrigerator and a warped piece of metal off a shelf next to his front door. This copper bullet, he tells me, came out of an elk he shot in the nearby Gros Ventre Wilderness. He keeps it handy for show-and-tell opportunities like this one.

Taylor directs my attention to the girth of the spent copper round, which looks nearly identical to the flower-like Nosler E-Tip copper bullet Yanke held in his hand in Enterprise. The wider the path through the animal, he explains, the more damage and trauma the bullet generates, and the faster the animal dies. That elk he shot in Gros Ventre had dropped quickly.

“It’s hard to kill animals,” says Taylor, his eyes not hiding the fact that he still hasn’t recovered from sacrificing several of his older chickens over the previous few days. “No one wants an animal to die slowly.”

Lead ammunition, including the Federal Premium Ammunition’s Power-Shok soft point that Yanke shot into the other rain barrel, naturally smooshes like the cap of a mushroom when it strikes. A copper bullet is simply designed to mimic that mutation by opening up into petals upon impact.

Travis Ryan, a spokesperson for Barnes Bullets, noted that this engineering has improved significantly since his company created their first prototype copper bullet in the early 1980s. Now, the diameter of their bullet at least doubles when it hits its target, while maintaining enough energy to penetrate deep into the animal.

The NRA awarded Barnes best hunter ammunition product of the year in 2012 for its copper bullets. Today, more than 40 U.S. companies manufacture or load non-lead bullets. Yet finding copper ammunition can still be difficult, in part because it is not yet available in all the shapes and sizes necessary to fit the extensive arsenal of guns in America. For some of these guns, experts agree that a transition to lead-free is less urgent. Shotgun and muzzle-loading bullets, for example, move slower and are, therefore, less prone to fragmentation. But plenty of speedier ammunitions remain limited to lead.

A lack of marketing may also keep some shoppers from finding and adopting the alternative ammunition. Take, for example, Barnes’ VOR-TX copper rifle bullets. Neither the front packaging of the box nor its listing on the outdoor sports store Cabela’s website make mention of it being “copper” or “lead-free”. The information does finally appear when you click on the item itself and scroll down to the fine print. What’s more, there is no way on Cabela’s website to search ammunition by material.

The biggest copper deterrent for those hunting for ammunition, according to the firearms industry, is that copper comes at a higher price than lead. As a material, it is more expensive, and its characteristics — hardness and melting points — require additional energy and tooling inputs, explained Ryan Bronson, conservation and public policy director for Federal Premium Ammunition.

While Bronson noted his company’s opposition to efforts to take away a hunter’s option to shoot with lead, Federal unveiled a new line of copper rifle ammunition last summer. A box of 20 rounds sells at Cabela’s for about $28 — within the price range of popular lead bullets. The product’s packaging also does include reference to “copper” — a sign that the situation may be improving, according to Henderson.

The lingering, but arguably shrinking gap in the availability of copper bullets helped motivate California’s slow phase-in of its ban, said Clark Blanchard, assistant deputy director of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Office of Communications, Education and Outreach. “We hope manufacturers will catch up and produce more of the stuff as we get close to 2019, and that prices will come down,” he said, noting that he switched to lead-free himself this year and discovered that the price tag for a box was comparable — about $24 for copper as opposed to the $20 he previously paid for lead.

Even with a price gap, advocates note that ammunition accounts for a small proportion of the overall cost of hunting, especially for big game hunters who may shoot only a couple bullets a year. A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service survey in 2011 found that the average big game hunter actually spends more than $1,400 per year to hunt, including transportation, food and lodging.

“So far, we haven’t seen that people are going to give up hunting because they are required to use non-lead,” said Blanchard. When California made non-lead mandatory in designated condor ranges in 2008, he noted that they didn’t see a drop in deer tags for the hunters most affected. In fact, he said, there might have been a “slight uptick.”

Joseph Neveau, of Enterprise, has hunted deer and elk since he was 12 years old. Now, at age 64, he owns more than 30 guns. “I use them all,” he says, leaning against his Ford truck parked in front of the Eagle Cap Gun Range. He’s wearing a plain grey t-shirt and blue jeans, and clutching his Remington rifle.

Until this hot August day, the only bullets Neveau had fired out of this or any of his other guns had been made of lead. But Neveau has just agreed to buy a box of copper ammunition. He wasn’t sold by the same potential environmental or health benefits that had helped persuade Taylor. Rather, it was simply the performance of the bullets — and the chance to win a lottery. Elk hunters who voluntarily hunted with non-lead ammunition on the Nature Conservancy’s Zumwalt Prairie Preserve in Oregon during the 2016 season were entered into a drawing for prizes totaling $2,000. The incentive program launched as a partnership between the Oregon Zoo, the Nature Conservancy, the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife, and the Oregon Hunters Association.

The mix of shooters who showed up at Eagle Cap — among them a couple men in environmental t-shirts and another wearing an NRA hat — may not have ordinarily rubbed shoulders. But Brown, a hunter himself, suggests that there’s no reason environmentalists and hunting rights advocates should be at odds when it comes to the question of adopting non-lead ammunition. “This effort is pro-hunting and pro-conservation,” says Brown. “It’s about how the hunting community can continue to be leaders in conservation.” Theodore Roosevelt wore both hats after all.

But a deeper look at those defending lead ammunition makes apparent this polarizing debate is also largely about politics and money. The gun industry warns a “slippery slope” of regulation on guns and ammunition will follow any bans on lead bullets. Meanwhile, the lead recycling industry has direct profits at stake. The Association of Battery Recyclers intervened on a case brought by environmental groups that sought to force the EPA to ban ammunition containing lead components. The U.S. District Court eventually dismissed the lawsuit, siding with the recycling group, the NRA and the NSSF.

Lawrence Keane, senior vice president for the National Shooting Sports Foundation, speaks to the National Rifle Association at the 2012 Republican National Convention about attempts by environmental groups to force the Environmental Protection Agency to end the use of lead bullets — which Keane and other lead-bullet enthusiasts refer to as “traditional ammunition.”

The National Defense Authorization Act, signed into law in November of 2015 by President Barack Obama, includes several NRA-backed provisions including one that prohibits the EPA from banning lead ammunition under the Toxic Substances Control Act. The EPA confirmed that the TSCA reform bill passed earlier this year would not alter that lack of authority.

The industry appears to actively lobby on the issue at the state level as well. The NSSF’s spending in California, for example, spiked to more than $350,000 in 2013, according to data from the National Institute on Money in State Politics, while consistently staying below $50,000 during preceding and subsequent years. That same year, a coalition of gun rights groups formed the Hunt for Truth Association to “debunk the myths and misinformation about lead ammunition.” California Assembly Bill 711, the ruling that propels the state towards a lead ammunition ban, was among gun-related legislation approved by Democratic Governor Jerry Brown in October 2013.

Minnesota’s Henderson hinted at less direct methods that may also be used by industry to fend off regulations on lead ammunition. While all major U.S. ammunition manufacturers have begun making non-lead ammunition, he said, “The NRA hangs over their shoulders, daring them to promote their own products.”

Henderson helped to organize a roundtable discussion on the transition from lead to copper ammunition last August in Minnesota. He noted that he had invited a representative from Hornady to share information on the company’s new line of non-lead bullets. And the representative agreed to attend. However, Henderson recalled hearing from him a few days before the meeting. “He called and apologized because one of his superiors told him he would be fired if he showed up at our meeting,” said Henderson. (Hornady did not respond to a request for comment on their GMX rifle ammunition or the meeting.)

The defense strategies — from battling back legislation to interjecting questions over the science to framing the issue as a threat to the Second Amendment — appeared familiar to David Rosner, co-director of the Center for the History & Ethics of Public Health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. “So many of the tactics look just like what other portions of the lead industry did to confuse us about lead paint, pipes and smelters: Raise doubt about the ‘validity’ of the science and say we just need much more information,” said Rosner. “After that, the industry just said the information gathered was just not good enough because there are too many confounding factors and too many sources to blame our product.”

This playbook, perhaps drafted by lead paint manufacturers in the early 20th century, seems to have been revised and expanded over the decades by other industries that, too, have been forced on the defensive. Internal tobacco industry documents, for example, revealed how companies purposefully confused the public by manufacturing controversy. “Spread doubt over strong scientific evidence and the public won’t know what to believe,” one document advised. For decades, the industry continued to argue that there was no proof that cigarette smoking caused harmful effects and that the science purporting such hazards was shoddy or incomplete. They cherry-picked favorable studies and funded their own research to dispute links. The deceit and denial successfully delayed regulations. The flame retardant industry has reportedly enlisted similar tools to preserve its lucrative market when confronted by incriminating scientific studies and the threat of legislation.

A new study at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, is hoping to shed some light on individual hunters’ attitudes and beliefs with regard to lead bullets. John Organ, chief of the Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Units for the U.S. Geological Survey and the study’s lead investigator, says this would include an examination of where they get their information. “We are approaching this from an objective perspective — trying to understand what would influence hunter behavior and what would change hunter behavior,” Organ said.

Donald J. Trump made a campaign stop at the 2016 NSSF Shot Show, where he posed for a photo with Keane. The gun industry lobbies hard to protect the use of lead ammunition.

But that study is just getting underway, and it remains difficult, overall, to know just how big game hunters, police officers, and the public navigate the many conflicting arguments around lead ammunition. “For a lot of people, the only exposure they get around this issue is from groups saying basically that the science is all junk,” says Brown. “So it’s challenging to come back and present research to a group that’s been told this research is no good.”

What’s clear is that the 11th-hour directive to phase out lead shot on federal lands, which was issued by Obama’s outgoing Fish & Wildlife Service director, Daniel M. Ashe, two weeks ago, has been met with a fair amount of outrage within the industry, as well as from the association representing state wildlife agencies, who complained loudly that they were not consulted ahead of the order. With President Trump receiving prominent endorsements from groups like the National Rifle Association, the National Shooting Sports Foundation, and the Fraternal Order of Police during his bid for the White House, it seems unlikely that the convictions of lead ammunition enthusiasts will be challenged by the new directive for long.

Neveau, standing under the American flag we’d pledged allegiance to that morning, admits that he might be inclined to shoot a certain type of bullet just because he’s told not to. “I’m not a big environmentalist or a liberal, and I don’t want to be pushed,” he says. What he does want, he says, is a bullet that will mushroom and kill an animal fast. To that end, he certainly wants it to also shoot straight. Neveau tried several different copper bullets on the range and found his bullet holes grouped within one inch of each other. “You’re always looking for less than one inch,” he says.

Lynne Peeples writes about science, health and the environment from her home office in Seattle. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Reuters, Popular Science, Environmental Health News, and Audubon Magazine, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Part of the problem may be laws that are written that would make it difficult to produce lead free pistol bullets:

Armor Piercing is defined:

A projectile or projectile core which may be used in a handgun and which is constructed entirely (excluding the presence of traces of other substances) from one or a combination of tungsten alloys, steel, iron, brass, bronze, beryllium copper, or depleted uranium; or

A full jacketed projectile larger than .22 caliber designed and intended for use in a handgun and whose jacket has a weight of more than 25 percent of the total weight of the projectile

The second definition is the problem, as basically anything apart from the lead core is designated as the jacket. Repealing or rewriting this law so that it isn’t based on bullet composition would help.

Personally I would love to see a polymer type bullet for target shooting.

I agree with you

I’m not sure if rational arguments in support of lead are actually being sought or not, but I think what is missing here are two things, first a sense of scale and second, an explanation as to why lead is difficult for hunters to swallow. As to scale, the amount of lead fragments or scattered tiny lead shot is minuscule. Given how healthy eagle populations are, I doubt the gut piles are a significant factor in Eagle mortality, but if they are, then why not ban the discarding of gut piles? Let’s say you have to pack it out with you. Also, there are massive amounts of lead on construction sites and in decaying structures, why is there no concern over those? Finally, why can’t hunters give up lead? Because the alternatives (bismuth and tungsten – steel is not a suitable substitute, it doesn’t kill animals cleanly and it will not compress to go through older gun barrels) are more expensive by a factor of 10. And in many cases, there are no suitable non toxic loads at suitably low pressures for older guns. Hunters do more for species and land conservation than anyone; perhaps if those concerned about lead spoke with hunters and worked together toward feasible substitutes and timelines, everyone might be happy?

I always was concerned in this subject and still am, thanks for posting.

Yes, the toxic ammunition is a threat to wildlife that consumes the remains of animals shot by hunters.

BS. You will be long dead before lead bullets are gone. There are billions in homes across the world. People will make them and shoot them for the next 50 years or more. This is the first step of the slippery slope of banning guns and cartridges. Ammunition used for hunting vs the rest of shooting is like saying Off road truck crashes need to be stopped while on road is 5000 times that. No one is going to use copper bullets that are very expensive compared to lead plinking bullets for range shooting, plinking on the farm or country or back yard shooting. From lead .177 pellets to shotgun and pistol shooting the vast majority are mostly lead.

In the bigger scheme of things, considering Monsanto Corporation’s millions of gallons of glyphosphate herbicides, massive applications of insecticide, Aspertame, Sucralose widely distributed into the food supply, along with wind mills killing millions of birds annually, massive bird kill-offs from microwaves, this discussion is barely a pin prick into the real overwhelming sources of environmental toxicity. There are places in Oregon where mercury as well as lead are naturally occurring elements in the lakes and streams.

Big tobacco’s tactics parallel lead bullet manufactures actions? The two issues are completely different and the divergence explains why hunters will never back lead bans. I am stunned that the reporter failed to realize that, despite tobacco companies claims of tobacco’s safety, no citizen could ignore tobacco’s ill effects. This is not true of lead from bullets. The science regarding Condor lead blood levels still lacks proof that the lead was from hunter’s bullets, only claims that the isotopes match are offered as proof. It’s well known that they match many other potential sources as well. In hope of finding the true effect of lead, I perhaps someone will research the following: I’ve shot ground squirrels in alfalfa fields for many years. On average, I will kill 250 in an afternoon. The local raptors and seagulls react to gunfire as a dinner bell, arriving within minutes to dine and squabble over the lead shot squirrels. When the lead ban issue began to ratchet up, shooters began to pay attention to the gulls, because of their markings make it easy to identify individual birds. I have personally seen a dominant, voracious gull return for three years. This gull had consumed hundreds of carcass and never displayed sign of lead poisoning. In fact, I have never witnessed any bird suffering from lead ingestion. How can this be? It’s nothing new. No dead, lead poisoned waterfowl were found during the research that prompted the Federal ban. In fact, high tension power lines continue to kill many times more raptors than can be attributed to lead. The science on lead is based on projections- educated guesses being made by experts with a bias against hunting. If lead toxicity was the issue behind the California ban, why is target shooting exempt?

Also noteworthy is shotgun ammunition, which has a fairly long (recent) history in restriction of use for hunting (also some states/regions that limit hunting to only shotguns, though there’s been some revision of that more recently, but it’s one of the major reasons deer slugs and shotgun hunting are popular vs the generally more efficient and appealing deer rifles). However, there haven’t been any general bans on lead ammunition, just restrictions on when and where it can be used, thus not adding to the cost of target shooting, practice, or home/personal defense (or law enforcement/security). Plus, lead shot is hard lead alloy, and retains its mass very well, though birdshot is so fine/small that it’s going to get spread around. (using birdshot on pests/varmints would have been a major source of contamination further up the food chain)

And so far, restrictions on what ammo and weapons can be used for hunting in certain regions have been more sensible, rational, reasonable, and even when not actually ecologically sound or practical (ie based on false beliefs or bad politics) they’re at least moderate enough to not be horrific. (or something they’re reasonably effective at conservation/moderation of over-hunting, but are less ideal than more nuanced approaches … things like shotgun hunting seasons or ammo restrictions based purely on bullet diameter are indeed problematic: for example, if you wanted a reasonably effective, non-fragmenting substitute to a jacketed hollow point, one option would be a small bore, very long, relatively heavy bullet that would tumble substantially on impact … the same idea applied periodically to military bullet designs to maximize wounding potential without breaking the Hague Convention … meanwhile, police forces generally use hollow point ammo for its greater efficacy and are mandated to use such in some jurisdictions … sort of like with Tear Gas: an illegal chemical weapon if used in war, but rather commonly used by police, prisons, and security forces or even for personal self defense)

There’s also potential for much cheaper, lead-free ammo than solid copper or brass, or those using even more expensive metals like bismuth or tungsten. Mild steel and zinc cores for cheap, lead-free bullets should be viable for plenty of cases where lead’s sheer density isn’t required (which covers quite a few rifle rounds, particularly those common with military cartridges: and Russian/Eastern Bloc milsurp ammo is already usually steel-jacketed, steel-cored, with a little bit of lead used for balancing and as a binder, and some, like 7.64x54R even typically employ an air gap). For a wide variety of hunting-relevant cartridges, using somewhat longer bullets of lighter core alloys would result in good ballistics and low cost of materials, and would be adapting already common manufacturing methods. Meanwhile, hybrid construction methods could be used for existing hollow point designs with the bulk of material being a steel or zinc insert and a softer metal (like tin or a tin alloy) could be used at the tip to expand fairly similarly to lead alloys. (tin is expensive and would be uneconomical to use for bulk filler material, but fine for just the tip and probably better performing … or simpler/cheaper to manufacture than some specialized expanding copper hollow points, plus could definitely be used as softpoints where copper wouldn’t work at all)

Most of the current solid copper designs are overpriced, extravagant, high-end market gimmicks and good, mass market lead-free alternatives are few and far between. (I will say the lead-free copper-powder plastic/polymer bullets in .22lr are pretty decent and not horribly expensive for the moderate ranges they’re designed for, and trading penetration or expansion/fragmentation high velocity hydrostatic shock is pretty well suited to small game hunting and varminting) I would like to see Aguila try something with a long, lead-free bullet based on the deimensions of their heavy their SSS round. (poly-coated or lubricated die-cast zinc would probably work, and solid, swaged copper probably would as well, and both would probably stabilize better than their subsonic lead counterpart) Die-cast zinc would seem an obvious cheap, .22 LR possibility for light bullets, but I haven’t seen it tried commercially. (tin alloys yes, but those are more expensive than copper by a wide margin and poorly executed so far on top of that … but die-cast zinc should be pretty damn cheap and the only real special requirement would be sufficient lubricating coating or poly-coating to avoid zinc fouling the barrel … soft lead is also a problem for that, hence .22lr being heavily coated already, but different formulations might be required for the much harder nature of zinc, and poly-coating might be a better option to avoid barrel wear … then again, I’d think zinc-on-steel would wear less than steel-on-steel, which is what most cheap, FMJ ammo is in other calibers … I’d also expect Agulia to jump on the die-cast zinc bullet train first … possibly contracting to some Mexican Toy manufactuer for initial production, given … cheap, die-cast zinc toys made in mexico are fairly common)

Use of certain types of bullets/ammunition should be more the point, that and re-examining existing restrictions that make lead pollution and contamination worse, particularly those aimed at minimizing suffering and maximizing clean kills. (hollow point bullets are far more effective at killing than FMJs, or hard cast solid lead alloy ones, but they also contaminate a lot more of the meat … be it for human consumption or varmint carcasses left uncollected) OTOH, there also quite easily could be more optimized bullets designed with more appropriate lead alloys designed not to fragment, but to properly expand (true controlled expansion types), plus the older, but less effective softpoint bullet designs (popular 100 years ago and still moderately popular today) don’t tend to explode/fragment either.

Those still interested in ‘exploding varmints’ would be left to using lead-free ammo designed to segment/fragment on impact, which already exist in copper, brass, and polymer composite bullets. (though really, solids and FMJs on small game and various rodent and rabbit varmints are more reasonable)

The remainder would just be solid, soft lead .22 LR, which can’t really change for the bulk of bullets as they’re cheap, practice/plinking ammo as well as small game ammo. It would make more sense for shooters to collect their kills and supply their own targets/backstops to collect their lead when target shooting on federal land. (setting up backstops is already required for safety reasons in CA, so that’s pretty well covered).

The use of hollow point and segmented bullets in .22lr, particularly the hypervelocity sort are the really problematic ones for conatminating things with fragments. (ie even if carcasses were left, scavengers would be much less likely to eat a solid. 40-ish grain pellet of lead than they’d be to eat tiny fragments … and likewise anyone interested in using squirrel or rabbit meat for food really wouldn’t want those fragments or the totally shredded meat such bullets leave, even with the low power of a .22) Same goes for jacketed hollow points in .17 caliber rimfire cartridges: they contaminate things and destroy meat. (in those cases, FMJs are quire good on their own, and the velocity of those small, light projectiles is enough to cause a lot of cavitation)

Additionally, cheap, generic, practice ammo and military surplus are all FMJ, and even with lead cores, they won’t be doing much contamination. They’re going to be mostly used for target shooting and not hunting, and tend to overprenetrate/pass through game as such, plus the jacket greatly slows any leaching of lead into the environment if left in the ground. (also if consumed … though much less likely for a fairly large, solid/hard copper/steel jacketed chunk of metal to be eaten)

Solid, hard-case, flat-nosed bullets common in brush hunting also won’t be doing much contamination and are well suited to reasonably efficient kill shots (flat-noses are good even without expansion) albeit not generally suited to long-range shooting … but ideal for brush as they tend to punch through branches and such without deflecting.

And as far as ground contamination, I’d actually think .22lr would be the biggest contributor (outside of civil war era minie balls in the South), and that’d be an issue of people not setting up their own backstops to collect their lead … and, of course, .22 being the cheap, common, superfluous cartridge most popular the world over for target/recreational shooting and practice. (again, this would be solved, legally speaking, by requiring backstops to collect the lead when not shooting at public or private ranges)

I also assume .223 ammo was used for the test, so a common, but particularly bad example as far as hollow point bullet designs go. (a small, high velocity bullet with soft lead providing exceptionally poor mechanical stability and strength at those dimensions … also illegal to use for deer hunting in several states, while well designed softpoints and hollow points in typical .308 or the formerly dominant soft/flat points of .30-30 used for medium game hunting in the US should not behave like that … same for .35 Remington)

Banning lead and lead alloys entirely would be a poor solution for such. (restricted use in Condor zones in CA was a pretty reasonable move, though) We need a LOT more public education on guns, responsible use of guns, responsible hunting, gun safety, etc … but I won’t hold my breath there. (between the decline/elimination of things like Driver’s ed and Shop Class in public schools, at least in California, I’m not optimistic in a government-furnished solution and am more hopeful for independent, grassroots movements on the internet to help educate coming generations)

Okay I see no scientific studies. You need control groups and endless unbiased data taking. These scientist seem to have an agenda. They are only taking data and conjecture made on assumptions. And a consensus does not make something true.And why do gut piles have so much lead in them? What type of gut piles are they. and finding lead in birds does not mean it came from bullets. MOST ANIMALS 99% that i shoot have no wounds in the guts. this all stinks.

I cry total BS. This is just an other attack on guns, hunting and firearms in general. The goal is, if you can’t ban the gun, make the ammo so expensive or unable to purchase, as they are doing here in commie-fonia, without burdensome and oppressive govt regulations. We here in the “golden state” can now no longer purchase ammo online unless it is shipped to an authorized dealer, who in the near future will have to preform a backround check and keep a photographic record of all ammo transactions. They all will charge a fee making it MORE even expensive.

All of you in the still free states of America beware!! If you are not carful and fight this type of oppression in your state, you too will be californicated!!!

Good article…but not great. It completely misses the major discussion point of the effectiveness of lead versus non-lead ammunition for hunting. I have used non-lead ammo extensively (required where I hunt) and the performance compared to lead ammo for both accuracy and lethality on animals are pathetic. My personal experience does not support the ammo manufacturer’s and gun writer’s claims (who sponsors gun writers?). I would gladly adopt non-lead ammo once the performance meets or, preferably, exceeds the performance of lead ammo. Until then, my responsibility to humanely dispatch and recover the animals I am hunting equals or exceeds the potential impact of the lead I shoot.

“Even with a price gap, advocates note that ammunition accounts for a small proportion of the overall cost of hunting, especially for big game hunters who may shoot only a couple bullets a year.”

Fair ’nuff. But many shooters don’t hunt at all. I am one of them. And the cost of ammunition is easily the most expensive component in my shooting. I typically go through thousands of rounds of ammunition a year. A 20% (or more) increase in my costs is significant indeed.

All this “science” to tell us that lead bullets kill?

We like lead bullets because they’re more accurate. They function quite reliably. And are cheap.

Plus they kill.

With regards to lead in the environment. On the entirety of Earth lead is a naturally occurring element. Our use of it is of little consequence. Whether or not man has ever existed lead will still have been here. Everywhere. Stop pretending that man is having a bigger effect on earth than what we really are.

We dig lead concentrations from deep in the earth, make it into products that get dispersed quickly around the world to degrade as pollution that is very toxic. When the earth does this naturally, the timespan is very slow compared to the rate at which we humans dig it up. Over eons, organisms evolve defensive biology to cope with ambient levels, but greatly increased levels of lead overwhelm biologic defenses like a tidal wave of toxic effects. We have increased the exposures greatly, and the biology has not had time to adjust. Lead is devastating to current life quality.

Outstanding reporting! As a strong and longtime gun rights enthusiast, it’s refreshing to see a journalist write so articulately and evenhandedly on a firearms issue. This is exactly the kind of reporting that needs to diffuse into the general press, which routinely screws up–or worse, slants–any story having to do with guns. As for the content, I don’t hunt and so have no danger of eating lead particles. But I shoot at ranges, using lead bullets. This article convinces me it’s time to wear a mask or respirator while shooting, to not breathe in the vaporized lead. Thanks to publisher Deborah Blum for starting a science magazine that appeals to readers without advanced degrees in science and math. UNDARK rocks!

KEEP DRINKING THAT KOOLAID

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10393-016-1177-x

Health and Environmental Risks from Lead-based Ammunition: Science Versus Socio-Politics

Despite overwhelming scientific evidence and increasing policy imperatives, nationally regulated bans on the use of lead shotgun and rifle ammunition are few. North American and European arms industries have developed non-toxic shot and bullets that are as effective and comparably priced as their lead counterparts (Thomas 2015). Our understanding of the deleterious impacts of this form of lead exposure on wildlife and humans will change little with further scientific research, no more evidence is required. The same rationales that were used to remove lead from gasoline, paints, and household items should be applied to lead-based hunting ammunition, nationally and internationally. This is now a socio-political issue.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/wol1/doi/10.1002/wsb.731/full

Metal Deposition of Copper and Lead Bullets in Moose Harvested in Fennoscandia

ABSTRACT Fragments from bullets used for moose (Alces alces) hunting contaminate meat, gut piles, and

offal and expose humans and scavengers to lead and copper. We sampled bullets (n¼1,655) retrieved from

harvested moose in Fennoscandia (Finland, Sweden, and Norway) to measure loss of lead and copper.

Concordant questionnaires (n¼5,255) supplied ballistic information to complete this task. Hunters

preferred lead-based bullets (90%) to copper bullets (10%). Three caliber classes were preferred: 7.62mm

(69%), 9.3mm (12%), and 6.5mm (12%). Bullets passed completely through calves (76%) more frequently

compared to yearlings (63%) or adults (47%). Metal deposition per bullet type (bonded lead core, lead core,

and copper) did not vary among moose age classes (calves, yearlings, and adults). Average metal loss per bullet

type was 3.0 g, 2.6 g, and 0.5 g for lead-core, bonded lead-core, and copper bullets, respectively. This

corresponded to 18–26, 10–25, and 0–15% metal loss for lead-core, bonded lead-core, and copper bullets,

respectively. Based on the harvest of 166,000 moose in Fennoscandia during the 2013/2014 hunting season,

we estimated that lead-based bullets deposited 690 kg of lead in moose carcasses, compared with 21 kg of

copper from copper bullets. Bone impact increased, whereas longer shooting distances decreased, lead loss

from lead-based bullets. These factors did not influence loss of copper from copper bullets. In conclusion, a

significant amount of toxic lead from lead-based bullets is deposited in the tissue of harvested moose, which

may affect the health of humans and scavengers that ingest it. By switching to copper bullets, Fennoscandian

hunters can eliminate a significant source of lead exposure in humans and scavengers.

Very nice article. I’ve seen many other sources of similar info but this one has caused me to give some serious thought to the issue. I will do some personal research on my own & I DO have lead-free bullets in my inventory of reloading components & will certainly use them for hunting.

In my experience most rifle bullets pass through the targeted game so one could get the impression that there are no remnants left behind; apparently not the case. Good work!

Yes, lead is a very soft toxic metal… it rubs off as it passes through, and fragments easily.

Any people that fish by using lead fishing sinkers are poisoning themselves, the fish, and supportive species by the pollution they cause. If legislators take their grandkids out to teach them how to fish, and handle their contaminated tackle boxes with bare hands are poisoning the people they love the most by contaminating their sandwiches, apples, cooler ice, boat bottoms, and the fish that are taken home and fed to the whole family. We poison what we love, out of ignorance, arrogance, and political refusal to read and understand the vast body scientific research that already is available about lead poisoning…. all because we just cannot bother to figure out how else to weight our fishing lines. The legislators prevent departments of environmental quality and health authorities from doing due dilligence because of ignorance, and fear of upsetting the industry lobbies that pay for their elections. A more sane future in our pacific northwest demands better accountability from us, to allow the children of our children, and their children to to be provided the beauty of the land and waters we have borrowed the from them. We must do a lot more to educate ourselves, drop our irresponsible fishing practices that cause lead pollution and harm across the land and waters. Go to a hardware store, buy a cheap lead check swab kit, test you tackle boxes, and learn how to fish without using lead to weight your lines. Be more responsible. Hunters and fishers, both, pollute the lands and waters they say they love. Ignorance is correctable, stupidity caused by chronic accumulative lead poisoning is not.

I read articles about lead often and not one has ever mentioned lead as a by-product of mining. In silver mining there is often a lot of lead for every little bit of silver. It has to go somewhere, and they chose to profit from it rather than go to the expense of properly disposing of it. So, the push to keep lead ammo comes from further back than ammo manufacturers and lead recyclers. Good work and keep digging!

The efficient functioning of our brain is our most essential and valuable characteristic, if you don’t have that, what have you really got? Chronic low dose repeated exposures are very harmful to exposed organisms. Vast quantities of research have been done, with plenty of overlapping and validating checks and balances to cover less than perfectly done areas of any individual papers. The validity of the totality of this body of scientific knowledge is overwhelmingly apparent to the research community. Lead is a toxicant that is accumulative in the bones after circulating in the blood as blood level. Blood lead is not a very good indicator of body burden accumulation, it is only an indication of recent exposures. You can have very high body burden but only low blood lead levels at any point in time. The bone lead is much more significant in the long run, because as organisms become stressed, from illness, old age, or pregnancy the body seeks to mobilize calcium out of the bone stores, but the lead comes out with it to recirculate and do damage at just the most vulnerable stressed times for the organisms. Exposed organisms often need two to four times the learning experiences to realize the consequences of their actions, a devastating effect of lead. Lead has very many adverse physiologic effects on many pathways in the body. Our brains are precious, it is crazy to argue for maintaining continued accumulation via preventable exposure scenarios. Lead makes us less able to think…. think about that!

As a student of public health, it is so nice to find articles that are well researched and include observations from all sides. This article was well written, well thought out, and the use of outside resources accentuated the validity of this topic. I will be using this article for a class assignment. Props to the author! I look forward to reading more about this topic in the weeks and months to come.

Wow. This packs a real punch — powerful and well-researched!!

D

Excellent article. Lead robs children of there potential – there is no good reason to use lead based ammunition.

Great in depth review of both sides. As a wildlife rehabber of 30 years … I wish we had access to lead blood level machines in those early days. Lead pellets would show up in x-rays of obviously gunshot animals… but it was much more difficult to isolate lead in animals that ingested pellets or fragments and we often assumed the animal got into rat poison or some agricultural agent.

My simple read on lead is that the paint companies and the gasoline companies did not go quietly into unleaded products …. BUT they eventually did because the science – and the potential lawsuits- were clear to them. They were spreading a dangerous toxin! How is it that the ammunition companies are exempt from liability for promoting the deposit of this toxin in public prairies, woodlots and riparian areas? Shouldn’t the “traditional ammunition” supporters be responsible for supplying lead testing machines to every wildlife rehab center? or at minimum admit that traditional ammo ( arrowheads) were lead free!

I am so moved to see a national discussion of the lead deposits on public lands before my Montana Representative Ryan Zinke becomes the next Secretary of the Interior that I started a change.org petition to show Representative Zinke see there is strong Montanan and nation wide support for common sense effort to replace lead with better alternatives! Keeping toxins out of our wildlife and wild places – and off our dinner plates, is not a second amendment issue! Please continue to fan the discussion and consider signing and sharing the petition.

Very thorough and excellent reporting. I miss the days of long pieces and solid research.