Enrico Fermi lived and breathed physics. As a youngster in Italy, Ph.D. not yet in hand, he taught himself the novel theories of quantum physics and relativity. As he lay in a hospital bed nearing death from stomach cancer in 1954, at the too young age of 53, he kept a tally of the fluids his body was absorbing by counting off the drops of his intravenous drip while looking at a stopwatch. In between, he changed the world.

BOOK REVIEW — “The Last Man Who Knew Everything: The Life and Times of Enrico Fermi, Father of the Nuclear Age,” by David Schwartz (Basic Books, 480 pages).

David Schwartz, the author of this authoritative new biography, tells us that at least two of Fermi’s colleagues thought of him as “the last man who knew everything” (hence the book’s title). This was not literally true, of course. Of the arts, music, literature, and history he knew little; he wasn’t even particularly knowledgeable about science, beyond physics. But within his domain, he was the master: He knew everything there was to know about the workings of the physical world, at a time when such knowledge could (just barely) be contained in one individual’s brain.

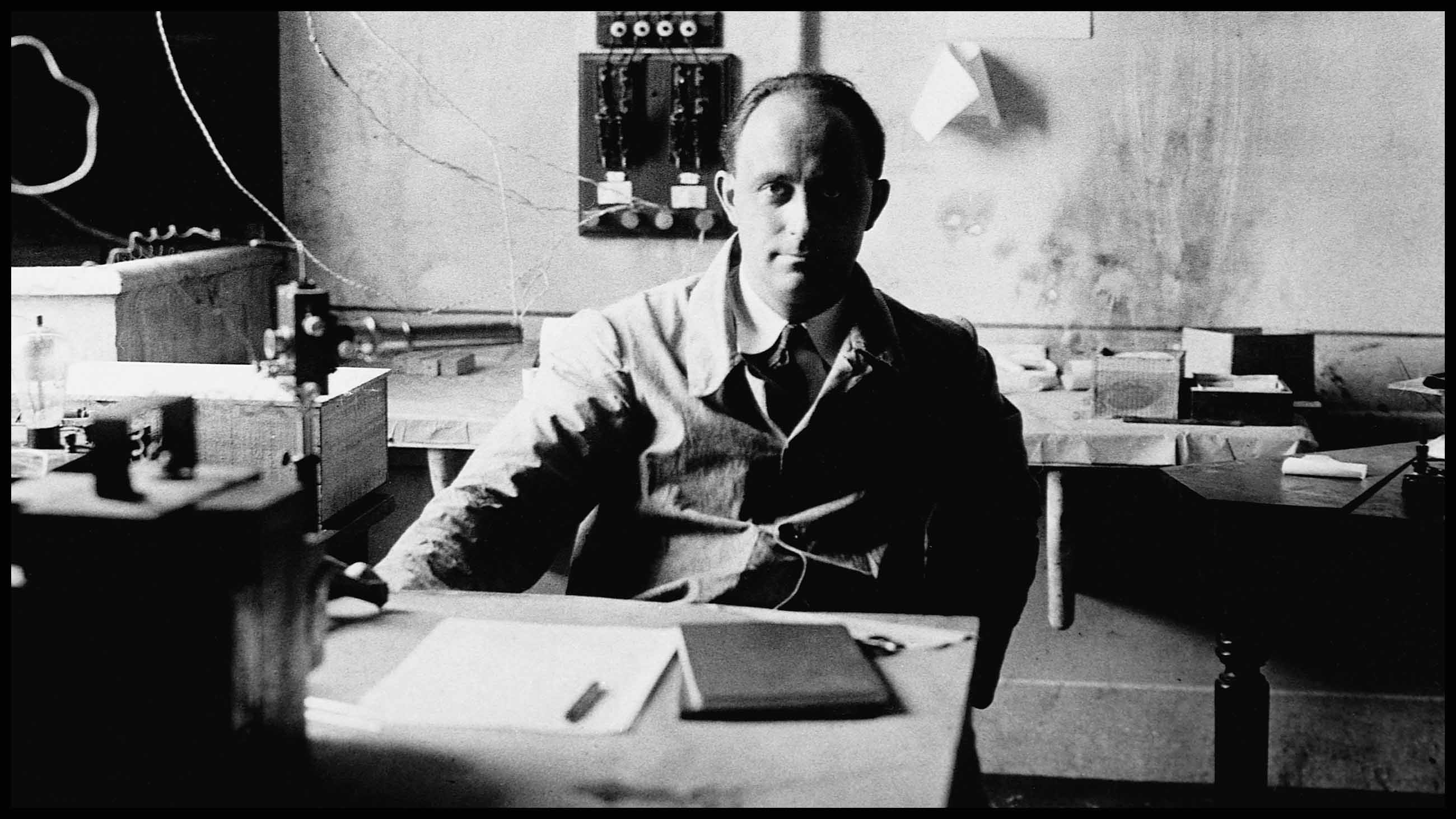

Though already drawn to physics as a child, his immersion in study may have been accelerated by the untimely death of his adored older brother, Giulio, when Enrico was 13. Around the same time, he learned the techniques of projective geometry. As an undergraduate, he required so little effort to ace his courses that there was time left to read physics journals in the library. He was a diligent experimentalist and a formidable theorist, equally at home in both worlds. He was often seen clutching a slide rule. What he learned he eagerly taught to others. He loved being in front of the blackboard; he was passionate about instructing the next generation of physicists. (Five of his students would go on to win Nobel Prizes.)

While he made important contributions to astrophysics, particle physics, and statistical mechanics, it is his role in harnessing the energy of matter itself — the energy locked inside the atom — that dominates any discussion of Fermi’s legacy. He was in his early 20s when, in an analysis of Einstein’s theory of special relativity, he noted that if one “could liberate the energy contained in one gram of matter” it would yield “more energy than exerted by a thousand horses working continuously over three years.” He added that it was unlikely this could be achieved in practice in the near future — just as well, since “an explosion of such an awesome amount of energy would blow to pieces the physicist who had the misfortune of finding a way to produce it.” Schwartz notes that at this early stage in his career, Fermi could not have imagined that he would in fact be that physicist.

Fermi came of age just as relativity and quantum theory were rewriting physics; he was born at just the right time to ride this new wave of learning and to play a leading role in the transformation. It was, however, not a good time to be an Italian physicist, especially one with a Jewish wife. As Schwartz explains, Fermi had a complex relationship with the fascist government of Benito Mussolini. He relied on government funding, and “was certainly willing to play Mussolini’s game, lending his name and his scientific prestige to the new fascist institution.” He notes that Fermi “was personally conservative and may at some level have approved of the stability that Mussolini brought to Italy, despite the regime’s use of thuggery and violence.” Fermi either backed the regime or at least made a point of appearing to back it; in return “his work was supported without interference.”

At first, Laura’s religion was a non-issue. Italy did not have the kind of deep-seated anti-Semitism that permeated German culture; many prominent Jewish families were considered as thoroughly Italian as their Catholic neighbors, and many Italian Jews supported Mussolini. In fact, the main reason the Fermis didn’t move to the United States earlier — there were multiple offers — is that Laura felt a deep attachment to her home country, and to Rome in particular. However, as the bond between Mussolini and Hitler strengthened, and Italy increasingly fell under Berlin’s control, she relented; the family moved to New York in 1938, stopping in Stockholm for Fermi to receive his Nobel Prize. As an added precaution, Laura converted to Catholicism to avoid any problems during their passage through Germany. (Laura’s father, Augusto Capon, who had been an admiral in the Italian navy, was eventually deported to Auschwitz, where he perished in 1943.)

In the 1930s, Fermi had already begun to investigate the peculiar properties of what we now call the weak nuclear force, the force that governs certain kinds of radioactive decay. Of particular interest was the idea of a nuclear chain reaction. When heavy, unstable atoms (such as certain isotopes of uranium) decayed, neutrons were released; and those neutrons in turn could trigger further reactions, possibly without end (or at least until the available nuclear material was used up). Although the idea of a chain reaction had been put forward by the Hungarian scientist Leó Szilárd in 1933, it was a trio of scientists, Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner, and Fritz Strassmann, who first showed that one could use fission to spark the chain reaction. By the time Fermi took up his new job at Columbia University, it was clear — at least to him and his inner circle, if not yet to the larger physics community — that scientists would soon learn how to create a new and terrible kind of explosive device by harnessing the chain reaction. It was simply a question of which nation’s scientists would succeed first.

The story of the Manhattan Project is well known, but considering its historical significance, another take on it — in this case, from Fermi’s point of view — is welcome. This is the book’s middle, and certainly most riveting, section. Events unfold quickly. On December 2, 1942, Fermi — now working at the University of Chicago — achieves the first artificial, sustained nuclear fission reaction in a squash court underneath the bleachers of the campus’s old football stadium. (A 12-foot-tall abstract bronze sculpture by Henry Moore now marks the spot.) Fermi, in spite of technically being an “enemy alien” in the eyes of the U.S. government, becomes a key player in its top-secret effort to create an atomic bomb. And yet the FBI kept a file on him, just as the Italian secret police had done in his home country.

Aside from illuminating the life of the great scientist, the book provides a welcome look at Laura Fermi, born Laura Capon, who would eventually establish herself as a writer; her first book, “Atoms in the Family,” was published shortly before Fermi’s death. One gets the impression of a more or less happy marriage, even if Laura was the target of much teasing and numerous childish pranks by Enrico and his friends, especially in their younger days. Although she was never far from her husband’s side, Schwartz makes it clear that Laura was kept in the dark during the Manhattan Project years; only after the atomic bombing of Japan, when the work was no longer a secret (or as much of a secret), did she learn what her husband had been up to.

As for Fermi himself, though his genius is not in question, he remains something of an enigma. Did the moral implications of the bomb weigh on him? Decisions on whether and where to drop the bomb were out of his hands, but one wonders if he felt some small fraction of the pain of those incinerated at Hiroshima and Nagasaki — or the even greater pain of those who survived. It’s not as though Fermi wasn’t a “people person” — those around him described him as warm, congenial, funny. But it was the world of physics, not the human world, that commanded his attention.

In Schwartz’s telling, Fermi had something of a fatalistic view of humankind. We would always fight; we would always build new weapons resulting in ever-increasing carnage. If Fermi was an enigma, so is the Chicago memorial. Its rounded top suggests a skull or perhaps a mushroom cloud. But Moore noted that the lower part of the monument has the look of a cathedral, “with sort of a hopefulness for mankind.”

Dan Falk (@danfalk) is a science journalist based in Toronto. His books include “The Science of Shakespeare” and “In Search of Time.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Also read 25 Interesting Facts About Enrico Fermi here: https://geniusmaco.com.ng/archives/25309