In a World That Still Traps Animals, Can Science Limit Suffering?

An old coyote, a female, lived for years in the Sonoran Desert, in south-central Arizona. She would have subsisted on small mammals, insects, cactus fruit, and lizards. The spines of desert plants lodged themselves beneath her skin, and, with the years, her teeth grew worn.

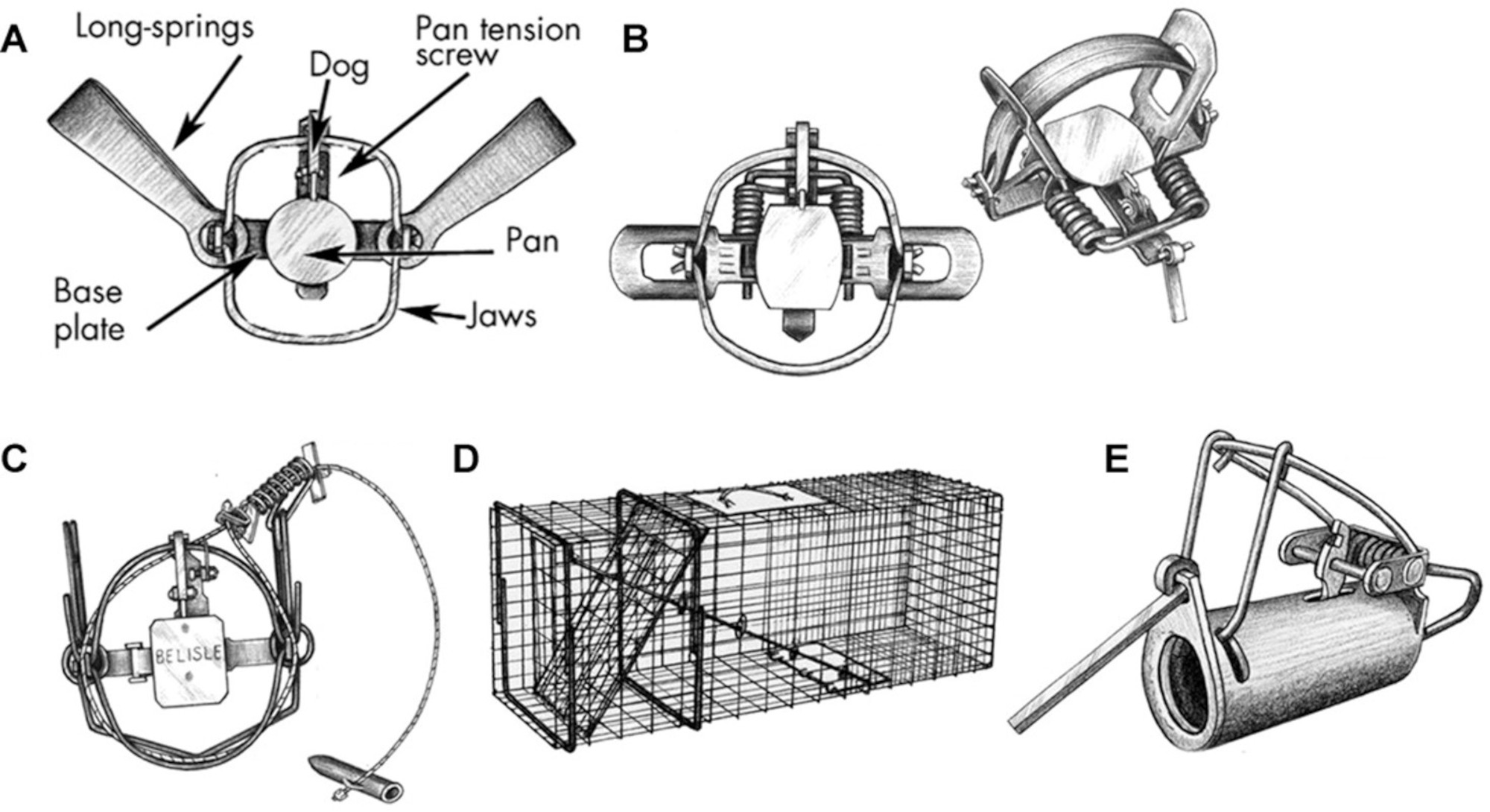

Sometime on the night of November 3, 2020, while crossing a sheep ranch outside Casa Grande, the coyote stepped on a 24-ounce metal puck equipped with a pair of powerful music-wire springs. The trap was a 450 offset jaw model, manufactured by Minnesota Trapline Products and built, according to the company’s website, “to hold the meanest, nastiest coyote.” When her front right paw landed on the device’s metal pan, a pair of smooth-edged jaws snapped onto her sinewy ankle and held her fast.

In the morning, the trapper, a biologist, arrived. He took notes on the animal’s condition, and he shot her in the head.

In the 2018-2019 trapping season, licensed trappers caught more than 2.7 million furbearing animals — a category that includes coyotes, beavers, raccoons, mink, and wolves. They use devices like the Minnesota Brand 450, as well as traps that snare animals in loops of cable, or break their necks with the force of powerful springs, or hold them underwater to die. Many trappers skin the animals to use or sell the fur. Others, often working in pest or invasive species control, may just dispose of the remains. Occasionally, trappers eat the animals they catch.

The Casa Grande coyote, though, was bound for a walk-in freezer in Wisconsin. Months later, a researcher would slice the skin off its body, and a wildlife veterinarian would spend around an hour inspecting the animal, cataloging any injuries caused by the trap. Another researcher would then feed those results into a dataset, part of a 25-years-and-running effort to quantify the damage that specific traps inflict on animal bodies.

People have trapped animals for millennia, seeking both fur and food. In North America, where fur propelled 17th century European profit-seekers into the continent’s vast interior, wild pelts were grossing an estimated $200 million per year as recently as 1983. (Adjusting for inflation, that’s more than $500 million today.) Faced with slumping global sales, the market has cratered in recent years. Guy Groenewold of Groenewold Fur and Wool Company, the country’s largest wild fur buyer, estimates the North American wild fur market is today worth around $25 million.

Still, around 175,000 Americans trap, according to one 2015 estimate, and trappers continue to gather at annual rendezvous and maintain what some describe as a vibrant, if endangered, subculture. Trapping for pest control and to limit invasive species remains common, too, both in the U.S. and abroad. In 2020 alone, for example, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s wildlife control division trapped and killed 22,067 beavers and 18,545 coyotes, according to federal data.

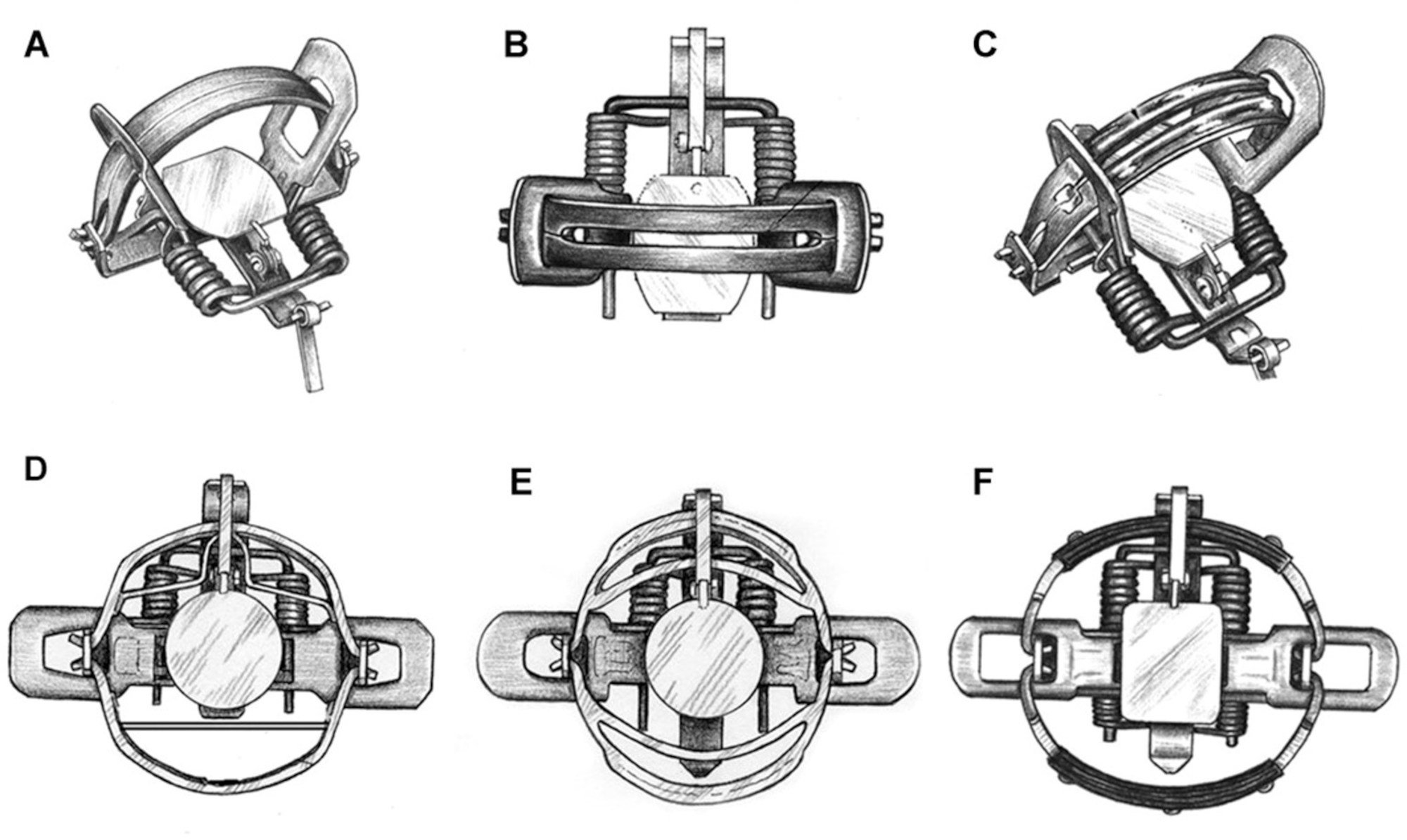

But since at least the late 19th century, some people have expressed concern about the pain that animals experience in traps. So in the 1970s and ‘80s, scientists in several countries, backed by funding from governments and the fur industry, began studying the mechanics of animal traps — and the damages they impart — in detail. How long does it take for animals in lethal traps to die? Are some trapping methods better than others? And in traps that aim to restrain animals, rather than kill them outright, what kinds of injuries do they sustain?

In pursuit of those questions, researchers have drowned beavers, necropsied wolves, and probed the eyeballs of dying cats. They have developed an internationally recognized scoring system to chart the severity of trap-induced injuries, and they have established standard ways to gauge when an animal reaches the threshold of death.

Today, experts in the U.S., Canada, New Zealand, Russia, and other countries continue to analyze trap performance. Their work receives little public attention, and the data is rarely published. But regulators take the findings and use them to develop trapping rules and guidelines that, at least in theory, govern the killing of millions of animals worldwide each year.

The U.S. trap research program launched in 1997, under the auspices of the nonprofit Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, which represents the interests of North American fish and wildlife regulators. According to the program’s leader, Bryant White, the initiative has studied close to 10,000 dead furbearers, evaluated more than 130 traps, and enlisted the help of around 2,000 volunteers. So far, White said, the U.S. effort has cost around $15 million, mostly from federal funding. White describes it as “the largest trap research project ever conducted.”

The results inform standards called the Best Management Practices for Trapping in the United States, or BMPs — essentially, a seal of approval saying that certain devices offer an effective, efficient, and relatively humane way to trap a particular species of animal. Trapping advocates say programs like the BMPs have made trapping more humane, and that they demonstrate that trapping can be a modern, responsible way to manage wildlife populations and harvest fur.

But the perception of all this research is fiercely polarized, as with most things involving trapping. Many Americans continue to think of the practice as wholly unnecessary, and local disputes — such as the March 2021 revelation that Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte had illegally trapped and killed a black wolf near Yellowstone National Park — can swiftly spiral into referenda on the ethics of trapping. State legislatures perennially field bills that would restrict the practice, with occasional victories: In 2019, for example, the state of California barred recreational and commercial trapping. One pending bill in the U.S. House of Representatives (which appears to have little chance of passing) would ban certain traps on some federal lands; legislation proposed in October 2021, with similar odds, aims to restrict the use of specific devices, including the kind of trap used on that Arizona sheep ranch.

Gov. Greg Gianforte, shown here at a 2018 event, received a written warning after illegally trapping a black wolf last year.

Visual: Photo by William Campbell/Corbis via Getty Images

The scientific field itself is also riven by divisions. An insurgent group of wildlife biologists, led by the French-Canadian trapping expert Gilbert Proulx, is now challenging influential international standards, arguing that they’ve done little to protect animal welfare. Two years ago, Proulx and three colleagues published a paper contending that those standards “perpetuate animal pain and suffering on an enormous scale.” In November, Proulx convened a group of scientists for a virtual conference on how to improve mammal trapping.

Little of this is likely to satisfy animal rights advocates, some of whom see the very practice of trapping an animal as inherently cruel, regardless of the trap’s performance. And, as the broader culture grows more sensitive to the suffering of certain animals, it raises questions about how much animal pain societies should accept — and what science can, or cannot, offer in pursuit of that elusive question.

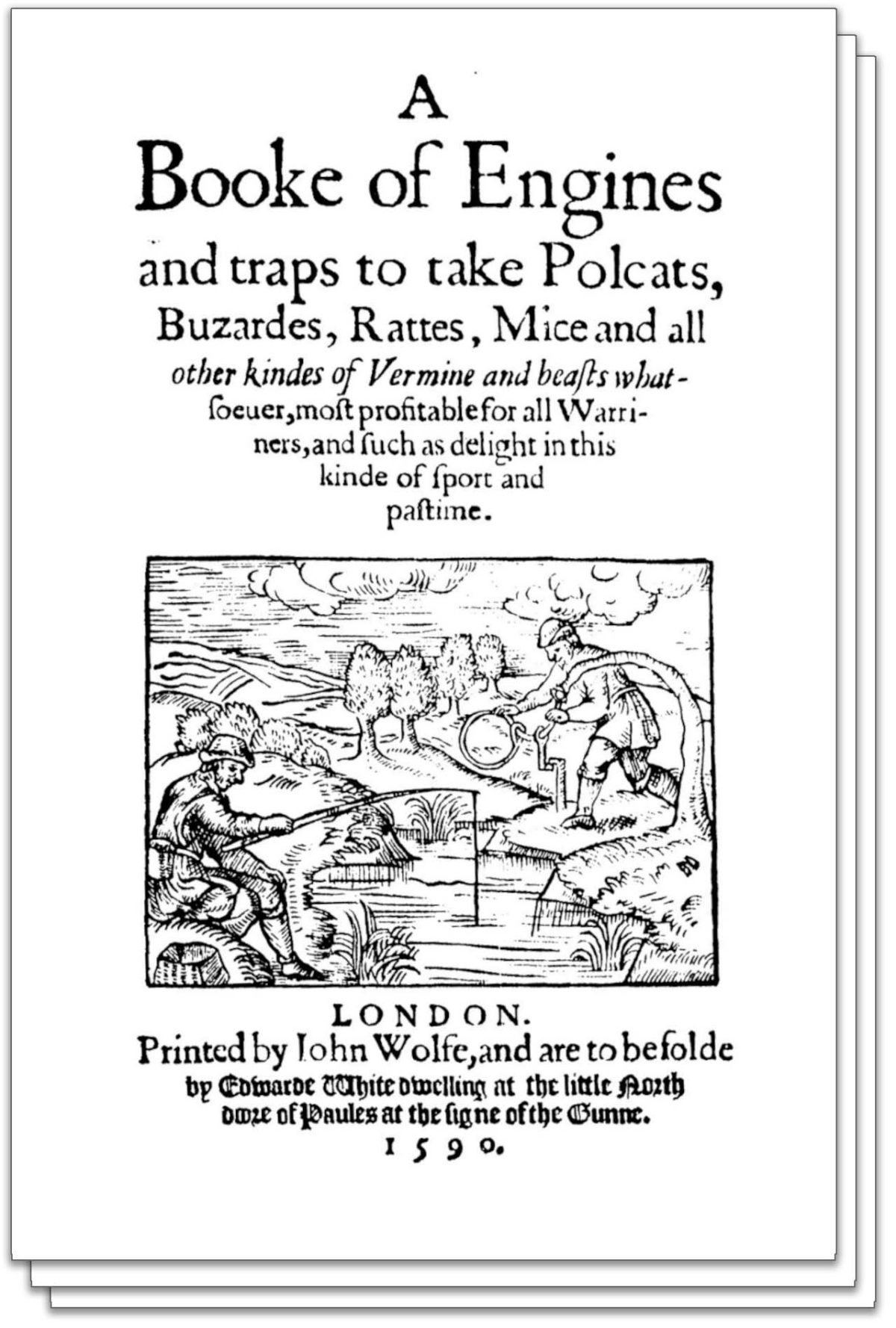

Over the years, people have come up with a diverse and sometimes ingenious array of tools to catch animals and hold them still: traps that pin down bears with heavy stones, snare the necks of ground squirrels, or use sticky lime to bog down birds on baited branches. In one classic treatise on the practice published in 1590 — fully entitled “A Booke of Engines and Traps to Take Polcats, Buzardes, Rattes, Mice and All Other Kindes of Vermine and Beasts Whatsoever, Most Profitable for All Warriners, and Such as Delight in this Kind of Sport and Pastime” — the English writer Leonard Mascall details one trap that strangles mice inside small holes, and another that looks like a three-pronged fish hook hanging from a tree. (A fox, Mascall claimed, will leap into the air to grab bait off the trap, “and when he catches the hooke in his mouth, he cannot deliver himselfe thereof.”)

Indigenous people in the Americas had been trapping for generations when, in the 17th century, European traders fanned out across North America to acquire the pelts of beaver and other animals, hoping to feed a seemingly bottomless demand for fur in Europe. As Europeans themselves began trapping more in the 18th century, many lugged bulky steel devices across the landscape, designed to clamp animals’ legs in their powerful jaws. The trappers’ methods could be violent but effective.

The early animal welfare movement in the U.S., said historian Janet Davis, focused on working animals like horses and mules. But eventually some advocates did turn their attention to trapping, which was often caricatured as a cruel pastime of poor country people. In 1925, a group of American animal advocates formed the Anti-Steel Trap League. The group pushed for legislation to ban those heavy metal traps, and anti-trapping advocates did have some early success: The first humane trapping legislation in the U.S. dates to 1928, when the South Carolina legislature banned steel traps.

The cover page of Leonard Mascall’s classic treatise on animal trapping, published in 1590.

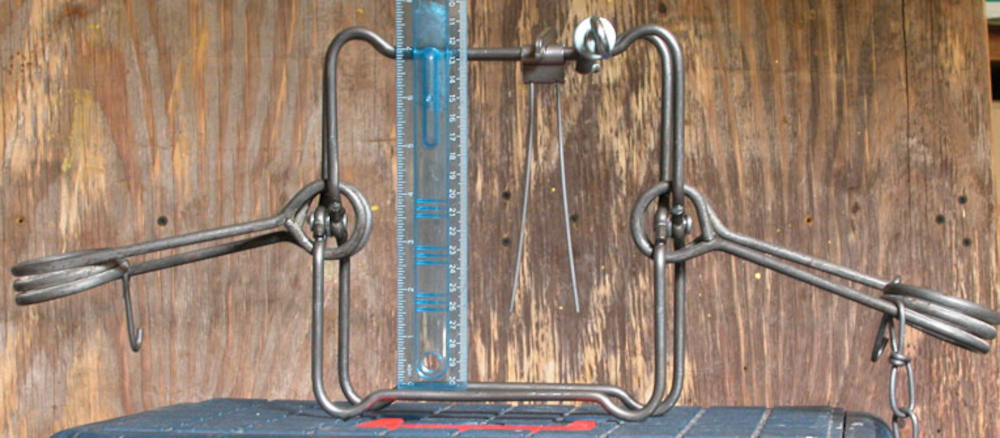

Advocates also began offering rewards for traps that caught animals with fewer or no injuries. A 1934 issue of the Anti-Steel Trap League News praises a man named Vernon Bailey for designing a device that, he claimed, could snag an animal’s foot more gently than the steel-jawed devices. The invention earned him praise (and perhaps a monetary award) from the league. North of the border, a young trapper in Canada’s remote Northwest Territories, Frank Conibear, had been feeling frustrated — and disturbed — by the chewed-off animal limbs he sometimes found left behind in his traps. In 1929, he began prototyping a new device, drawing inspiration from old-fashioned egg beaters and his mother’s embroidery hoops. After years of improvements, the Conibear body-gripping trap debuted in 1958. The device looks deceptively delicate, almost like something you could fashion from a pair of sturdy wire coat hangers. When triggered, it clamps down on an animal’s neck or torso, essentially crushing it to death. The device soon gained a reputation as a lighter, faster-killing, and more humane alternative to many existing traps, and today, body-gripping traps are among the most popular devices on the U.S market, often used to kill beavers, otters, and other aquatic furbearers.

By the 1970s, though, public opposition to trapping was intensifying in the U.S. and other countries. It was a pivotal moment for animal welfare activism. The philosopher Peter Singer published his groundbreaking book, “Animal Liberation,” in 1975, arguing that animals have rights, and that most humans are guilty of speciesism. Five years later, Ingrid Newkirk and Alex Pacheco founded People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, or PETA, which soon made headlines for its investigations and stunt-based campaigns.

Bruce Warburton, a trapper and biologist in New Zealand, was among the first scientists to publish research into humane traps. He began the work, he recalled in an interview with Undark, after the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals expressed concern about traps used to catch invasive possums. The SPCA said a certain new trap was more humane. Experts weren’t sure. Warburton volunteered to settle the question. In an early published paper on trap performance, he tests out seven kinds of traps, catching possums and taking fairly basic notes: In a live trap, how often was the animal injured, and how badly? In a killing trap, did the device seem to strike the animal in the right spot to kill it quickly? (The live traps left possums with “cut skin or fractured bone” around 70 percent of the time, Warburton found; the killing traps’ performance was mixed, but two models consistently clamped down on the animals’ heads or necks.)

Other teams were finding ways to identify more concrete numbers. In 1981, a Canadian committee recommended that animals caught in killing traps should lose consciousness within three minutes. Around that time, a pair of scientists at Ontario’s University of Guelph obtained several dozen wild-caught mink, muskrats, and beavers. They surgically implanted heart-rate and brain-wave monitors into each animal. The researchers also constructed a 3,200-gallon tank of water, equipped with a small platform, and placed two Panasonic video cameras next to the tank. They set traps that, when triggered, drove or held an animal irreversibly underwater.

One by one, the researchers put the animals in the tank. One by one, they entered the trap and plunged beneath the surface. As each animal drowned, the researchers monitored its heartbeat and brainwaves, trying to pinpoint the exact moments at which the animal stopped struggling, its brain activity ceased, and its heart stopped beating.

The mink and muskrats mostly appeared to lose consciousness within a few minutes of entering the traps. Beaver held on longer: On average, they struggled underwater for a full eight minutes, maintained brain activity for nine minutes, and exhibited a heartbeat for a quarter of an hour. One animal, labeled B25, struggled for nearly 13 minutes, and had a measurable heartbeat for 20. For mink and muskrat, the researchers concluded, drowning traps “fell within the tentative criteria of humaneness” established by the Canadian committee.

But for beaver, the researchers concluded, dying in a Conibear trap was probably better than running out of oxygen beneath the water’s surface.

As the Guelph researchers were drowning beavers, a small group of biologists was beginning to tackle a bigger question: Was it actually possible to scientifically study animal suffering?

At the time, some scientists were skeptical that animals had thoughts or felt pain at all — at least in a way comparable to human beings. Even among those who believed that animals could suffer, the new field faced doubters. “There may be other people, particularly scientists, who feel that it is quite impossible to study animal suffering in an objective scientific way,” Oxford University zoologist Marian Stamp Dawkins wrote in her 1980 book, “Animal Suffering.” But Dawkins would go on to argue that it was apparent to many people that animals had feelings. And even though animal pain can seem inherently subjective, she wrote, scientists could not simply opt out of studying it. In “Animal Suffering,” Dawkins called on researchers to use a range of methods to gauge how an animal experienced a particular stimulus. “We have to look, as it were, through many windows into a room that may look slightly different through each one,” she wrote.

The emerging field of animal welfare science soon developed a battery of metrics. Scientists chronicled injury to the body, of course. But they also recorded the levels of stress hormones in the blood and changes to heart rates. Researchers parsed animals’ choices to get hints at their preferences. In one 1986 study, for example, scientists restrained ewes using a device called a squeeze-tilt table, as well as by passing a strong, immobilizing electrical current through their bodies. When presented with a choice between the two methods, the sheep exhibited a preference for the squeeze-tilt table, suggesting that the electricity caused them greater distress.

At the same time these researchers were exploring the subjective experiences of animals, the trap research field was pushing toward a more mechanistic way of evaluating animal welfare. In 1983, Canada formally established a new trap research program. Three years later, at the request of Canada and several other countries, the International Organization for Standardization started the process of developing humane trapping standards. (Confusingly, the organization goes by the not-so-standard abbreviation ISO, rather than IOS.)

Headquartered in Geneva, ISO standardizes everything from the dimensions of cotton bales to the proper transport of uncrewed spacecraft. “I would give credit to Canada for thinking in those quantitative engineering terms,” said Gordon Batcheller, a retired wildlife biologist for the state of New York and a U.S. delegate to the ISO process. “After all,” he continued, “a trap is a mechanical device that has mechanical characteristics. What gets tricky is it’s being used for a biological system, namely an animal.”

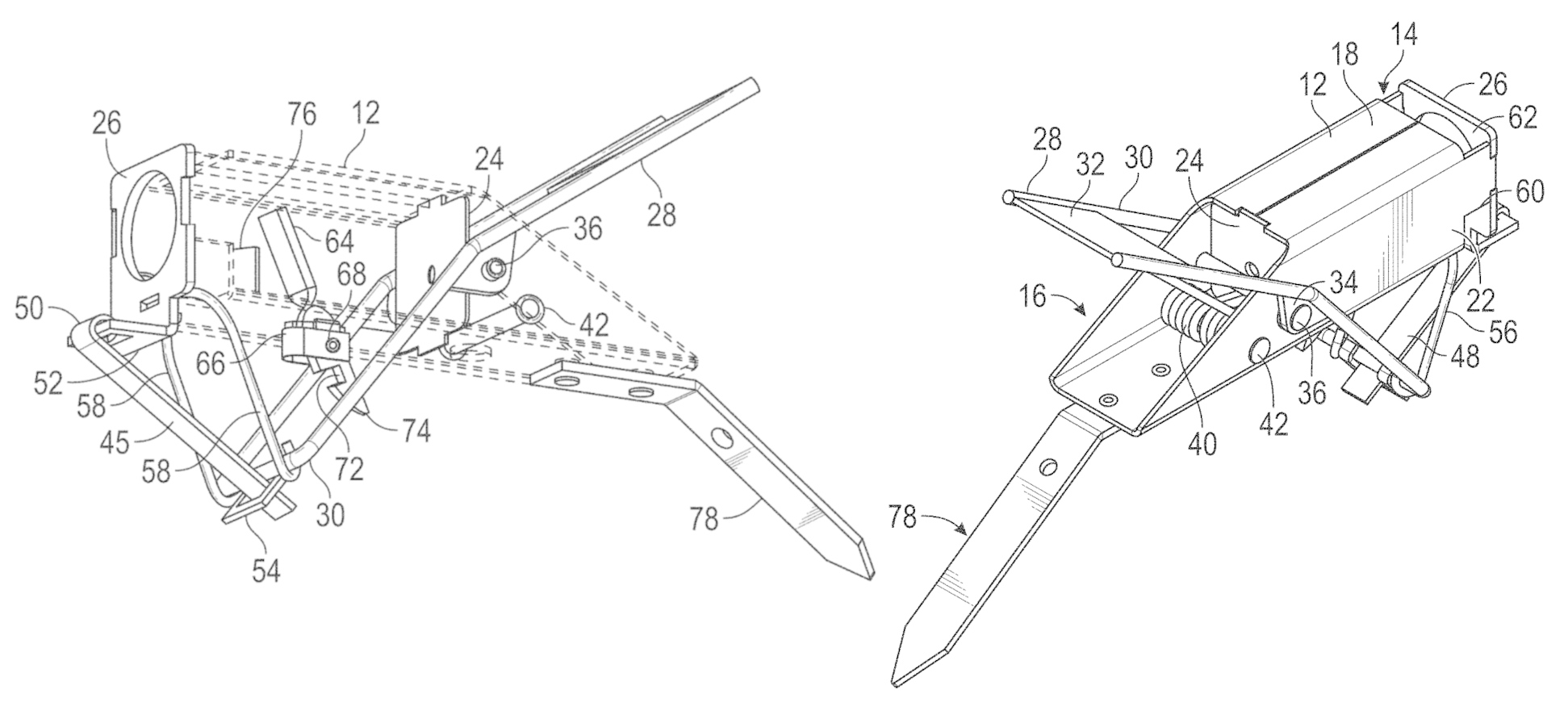

Delegates met for years, trying to hash out a uniform way to judge trap performance. As their deliberations continued, the stakes grew higher. In 1991, the European Union passed legislation that would eventually ban the import of fur from countries that permitted foothold traps, which advocates often describe as particularly cruel. (Even the name is contested: Animal rights advocates tend to call them leghold traps, while trappers and many biologists usually refer to them as foothold traps.) The U.S., Canada, and Russia — all major fur producers, and all places where trappers enthusiastically deployed such devices — reacted with alarm. After some diplomatic wrangling, the E.U. offered its trade partners an alternative: They could keep using foothold traps, provided they followed “internationally agreed humane trapping standards.” But no such standards existed.

Eyes turned to ISO. “All of a sudden, the work of ISO became extremely high profile,” recalled Batcheller. The talks, though, were running into obstacles. Donald Broom, an animal welfare scientist at the University of Cambridge who served as an advisor to the ISO process, recalled that some experts disagreed over even the fundamental question of whether animals feel pain. “There were scientists present who would not accept that there was any real sense of pain in the animals which were being trapped,” he said. “So it was as divisive as that.”

Talks finally stalled, Batcheller and other participants recalled, over how to define “humane.” Eventually, the delegates reached a compromise: The committee would lay out a unified system for measuring harm. But it would not tell individual countries how to apply it.

For kill traps, the ISO group decided, the key metric would be time to irreversible unconsciousness, or TIU. For restraining traps, the committee compiled a list of 34 different injuries, assigning each a trauma score based on its perceived severity. Under the ISO system, a lost claw counts for 2 points. Severance of a minor tendon or ligament is 25 points. A simple rib fracture counts for 30. The committee reserved a score of 100 points for the most severe outcomes — a spinal cord injury, a lost limb, blindness, death.

But, crucially, the committee did not actually determine when a trauma score or TIU crossed the line from humane to inhumane. They left that instead to individual countries, which began acting even before ISO published its final standard. In 1997, Canada, Russia, and the E.U. finalized a treaty called the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards, or AIHTS. That treaty set thresholds for injury severity in the case of restraining traps and maximum time to unconsciousness for kill traps. And it required each party to set up “appropriate processes for certifying traps in accordance with the standards.”

U.S. regulators were also feeling pressure. In the 1990s, advocates in several states managed to get anti-trapping referendums onto ballots. Some passed. Many wildlife managers saw trapping as a crucial tool for managing wildlife populations, and they grew alarmed. Batcheller and other biologists, he said, came to believe they had to respond to the pushback. “We know that Americans greatly value wildlife, and they have concerns about how animals are treated,” he said. “That’s clear and that’s legitimate, and we needed to address that.”

They had one problem: Joining a treaty developed by Canada, Russia, and the E.U. was out of the question. While the U.S. federal government can sign treaties, it wields little control over trapping laws, leaving those regulations to each of the 50 states, as well as independent tribal authorities. Getting them all in line would be impossible. Instead, the U.S. developed a sister process to the AIHTS, called the Best Management Practices. Under this process, the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies would test traps, and then issue nonbinding recommendations. States could use those recommendations to inform their regulations, and regulators would encourage trappers to voluntarily purchase BMP-approved traps.

The U.S. and the E.U. reached a separate diplomatic agreement, premised on the BMPs, that allowed fur to flow from American trappers to European markets. The Americans and the Canadians started working closely together and sharing data: Canada would test kill traps at an existing research facility in Alberta. The U.S., meanwhile, would focus on traps that restrain, but don’t kill, their quarry.

Trappers sometimes shy away from public scrutiny, and finding data on trap researchers’ work can be difficult. The Canadian trap research program, which is partially funded by Canadian taxpayers, has not published a peer-reviewed paper since 2001, and does not release data on how traps perform, other than the final list of approved devices, because of proprietary issues with trap manufacturers. In Russia, which ratified the AIHTS in 2008, a press officer for the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment said the trap research program existed, but that it had yet to publish any results.

In an email, Daniela Stoycheva, a press officer for the European Commission, declined to provide on-the-record answers to questions from Undark, or to make anyone available for an on-the-record interview. The E.U. does not have a unified trap testing system, instead leaving that responsibility to individual member states. (Some E.U. member states, such as Sweden, have implemented trap testing protocols, although it’s unclear how many national trap testing systems are currently functioning.)

For years, the U.S.-based Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies didn’t publish much data either. But last winter, the association’s Trapping Policy Program Manager for the last two decades, Bryant White, along with Batcheller and 12 other coauthors, published a long, peer-reviewed report on the first 22 years of Best Management Practices research, offering granular data on the performance of individual traps. The data paints a varied picture: For some animals, like red foxes, many traps performed well, with a dozen comfortably receiving the greenlight. For other animals, many traps performed poorly — foothold traps for striped skunks, for example, consistently caused severe injuries in tests. Cage traps tended to perform better than traps that seize the animal’s foot, and smaller animals often sustained more injuries than large ones. The researchers also evaluated how often a trap, when activated, actually catches and holds its target animal, and how often traps catch non-furbearers, including pets. Overall, 40 percent of traps tested for a particular species have failed.

The paper speaks to White’s somewhat unenviable role of bringing science to bear on a contentious topic with deep passions and cross-cutting interests. Each year, White and a team of advisers select a group of traps to test, and animals to test them on, based on reports from trappers and researchers. White then tracks down expert trappers, and each winter during trapping season, they go into the field alongside a research technician and set the traps. The animals they catch are typically shot with a .22, frozen, and shipped to Wisconsin via UPS.

In phone conversations last spring, White was frank about the challenges of implementing a trap research program, and happy to share details about his past two decades of work. The program has been criticized by both animal advocates and trappers. Many among the former see any kind of trapping as a non-starter, worthy only of an outright ban. Meanwhile, trappers have sometimes viewed the BMPs as potentially paving the way to just that, at least for some devices. “The trapper organizations were some of our biggest opponents, actually,” said White, who grew up south of Nashville hunting and fishing himself, “because they felt like this was government regulation that was unnecessary.”

Still, the Best Management Practices are not binding, and over time, White and other BMP affiliates say, those relationships have warmed — despite the 40 percent failure rate. “It does highlight that these standards are fairly stringent,” White said. “I hope what happens is that the traps that aren’t meeting the standard are going to fall into disuse at some point, that trappers are going to look at those and decide, yeah, I want to use the best thing I can.”

During the trapping season each winter, White continues to send out trapper-technician pairs. In the summer, a group of veterinary pathologists and wildlife biologists gather to necropsy the past winter’s haul. In recent years, the necropsies have taken place in Ashland, Wisconsin, at a Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources facility just a few blocks from the shores of Lake Superior.

“I call it the necropsy party,” White said.

The animals for the 2021 necropsy party arrived on a Sunday, in enormous blue coolers: 28 coyotes, 42 raccoons, and 8 bobcats, along with a few gray fox, a handful of Nebraska badgers, and one ringtail — a small omnivore, resembling a lemur, that someone had caught in New Mexico.

By 8:00 a.m. on Tuesday, coffee was bubbling in an urn, and more than a dozen coyotes were thawing on a gray tarp. A breeze from two small fans ruffled their fur, and the air smelled faintly of dog. White and a few other workers were finishing converting the large garage — used to store and service government vehicles — into a necropsy and fur processing shop. They had covered the floors with tarps, and spread out knives, loppers, and combs on wooden work tables. There was sawdust on hand, to sop up blood and stick to stray globs of fat. They had also set up three examination tables, each made of hard white plastic and furnished with a small drain for excess fluid.

The three veterinarians had not yet arrived. “When they show up here, the noise level will go up a couple decibels,” said John Olson, a retired furbearer biologist for Wisconsin, as he stood by the thawing tarp. He wasn’t wrong: The vets arrived together, in scrubs, and began loudly greeting and hugging colleagues. Olson calls them “the Three Amigos”: Lindsey Long, a wildlife veterinarian for the state of Wisconsin, with an upper Midwest accent and a small piercing in one nostril; Dan Grove, with the University of Tennessee, bearded and tall; and Kelly Straka, at the time a wildlife veterinarian for Michigan, enthusiastic and quick to share details about canid teeth or raccoon joint flexion.

A crew of 19 had assembled by 9:00 a.m., and in a brief introduction, White described the process. Everything began with personnel identified as “skinners,” who would select an animal from the tarp and heave it onto a table. A veterinarian would then perform an external examination, checking for lacerations, broken bones, damaged fur, and other external signs of injury, and dictating observations to an assistant. Once the vet finished the external inspection, the skinner would gently comb through the animal’s fur with a metal instrument to remove dust and matted blood. Then, the skinner would make an incision in the fur and beginning cutting it away from the body, often while the vets stood by, watching for signs of damage on the gradually exposed flesh.

Eventually, the skinners would deliver the body itself, often skinned except for the lower legs and skull, to the necropsy tables. The pelt would go to a station in the back of the garage, where a seasoned Wisconsin trapper in a camo polo shirt, Dennis Brady, oversaw the preparation of the furs. There, fleshers, using long curved blades, would rub the remaining fat and connective tissue off the inside of the pelt. Brady, wielding a staple gun, would then stretch and affix the fur to thin wooden boards, where it would dry. The Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies makes the furs available to wildlife agencies across the country for educational purposes.

As each skinned animal arrived on the necropsy tables, the vets inspected the tissues for signs of damage. To keep the process blinded, they knew only that the coyotes had been trapped by the foot, and whether it was a front- or hind-leg catch. Nobody told them which paw had been snagged, and none of the vets knew the model of trap under review. At times, a necropsy could take on the feel of a crime scene investigation. Was the line of hemorrhaging along one coyote’s side somehow related to the trap that caught its leg, or had it been caused by a shard from the .22-caliber bullet used to put it down? (Verdict: bullet.) Had another coyote’s hind leg broken before it died, or had it snapped somewhere in transit? (The lack of swelling indicated a posthumous fracture.) And what, exactly, had left such deep gouges in the hind leg of a trapped bobcat? (No one was sure; perhaps another bobcat?)

Straka seemed to be everywhere — inspecting animals assigned to her, popping in on other necropsies to see what they were turning up. Straka grew up in Minnesota; she has the outline of Lake Superior tattooed on one bicep. During the necropsying, she kept her blond hair pulled back with a stretchy purple headband and wore a pair of yellow rainboots decorated with cartoon chickens. She switched modes quickly: “How you doing little buddy?” she said one morning, gently running her hands over a coyote, before telling her assistant to note “a superficial abrasion on the lateral aspect of the right fifth metacarpal, approximately three centimeters in length.”

Straka was working as a wildlife veterinarian in Missouri when she met White, who soon recruited her to help with the necropsies. She was trained for BMP assessments by two older veterinarians, working alongside them to inspect animals. At the time of the necropsy event last July, she worked for the state of Michigan, monitoring tuberculosis in deer and overseeing a laboratory tracking animal diseases. (In September, Straka became the wildlife section manager for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.)

Trapping, Straka acknowledged, seems cruel to some people — but, she argued, it’s also a vital technique for controlling the populations of animals that, otherwise, would grow unsustainably. “Knowing that this is a technique that we need to manage populations, I want to be able to use the skills that I’ve been taught, the education I have, to make sure that it’s done as humanely as possible,” she said while she inspected the paws of a raccoon for signs of abrasion.

Because all the coyotes had been caught with foothold traps, those necropsies focused on the paws. By the time the animals arrived at the tables, most had been skinned down to their lower legs. Thin and muscled, they looked like flayed whippets. Sometimes, the trap had left visible abrasions on the outside of the foot. Other times, the damage seemed minimal until the vets peeled back the fur, exposing the delta of tendons and muscles that fan out beneath the skin. In some animals, the tissue was a healthy pink, the tendons taut and white. In others, the exposed flesh was dark with blood, the tendons damaged.

On the morning of the second day of necropsies, Straka was busy with a coyote that seemed to have sustained no injuries at all. Nearby, Grove was flummoxed: Even after cutting into the animal’s paws, he could not tell which had been in the trap.

In between them, Lindsey Long, the Wisconsin veterinarian, was working on the Sonoran coyote, which had been finally thawed, weighed (just 20.8 pounds, the same as some of the raccoons), and skinned. The catch had gone poorly: She had chewed her own paw in the trap. Frozen, shipped, and thawed, the limb now ended in a dark pulp of dried blood and hair. Slicing into the connective tissue with a scalpel, Long carefully peeled back the skin from the leg, working her way down the limb into the damaged area.

Trapped animals sometimes mutilate themselves when the trap cuts off blood — and sensation — to part of a limb. But such self-mutilation is rare in coyotes. A passing skinner looked in on the necropsy, and asked a question: Could the animal feel her paw the whole time she chewed it? Maybe, Long replied. It was hard to tell.

Earlier, White, who had trapped this particular animal himself, had come by. The coyote, he recalled, had tried to bite him when he first came upon it in the trap; she seemed almost berserk. In all his years of trapping, he had never seen one like it.

“That’s the kind,” he said, “that make you feel terrible.”

Such outcomes may be rare. But there’s extensive dispute over what to make of those kinds of severe injuries — and when they should disqualify a trap. Under the BMP process, researchers generally must necropsy a minimum of 20 animals before rating any particular device. No more than 30 percent of them can have injuries classed as “moderately severe” or “severe.” And once researchers tally up any lacerations, lost claws, or broken bones, the average injury score for all the animals necropsied needs to be 55 or lower. That means a trap can still pass despite a handful of bad outcomes. At least in theory, a device that causes 15 animals only mild bruising, and leaves 5 with broken bones and organ damage, could still squeak through.

To many trapping critics, those thresholds are far too lax. The problem with the BMPs, said Camilla Fox, executive director of the nonprofit Project Coyote, is “the amount of animal suffering that they still allow.” Fox wrote critically about the International Organization for Standardization process and related research as a co-author of a 2004 book, “Cull of the Wild.” The BMPs, she told Undark, are “woefully insufficient and fail to adequately address basic animal welfare standards.”

Some advocates also question the basic premise of such research. “As an animal advocate, I’m inherently uncomfortable talking about humane traps, trap testing, the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards, because I feel that it’s semantics,” said Lesley Fox, executive director of The Fur-Bearers, an animal advocacy organization in Canada. (Lesley Fox is not related to Camilla Fox.) Any trapping, she said, poses a basic moral problem for her. “We’re of the view that you could catch wildlife with pillows,” she said, “and a wild animal does not want to be restrained.”

For many wildlife biologists, those kinds of arguments can sound unrealistic. Even the best-designed traps will fail occasionally, they say. And trapping is an inevitable part of researching and managing ecosystems.

Their case goes like this: Human activities have dramatically altered natural landscapes, leading to explosions in the populations of certain species. Meanwhile, many people want to live close to nature, which leads to inevitable conflicts between, say, a human’s desire to have a passable driveway, and a beaver’s desire to dam the adjacent creek. To keep coyotes from overrunning cities, beavers from taking over backyards, and populations of raccoons from spiking in the suburbs, someone needs to manage their populations.

Americans can have a difficult time accepting that nature — or what we call nature — takes its current form through the routine interventions of well-trained technocrats. For many wildlife biologists, wildlife veterinarians, and others, though, this is simply a part of their professional work.

Sitting at his necropsy table in Ashland, Grove reflected on those broader stakes. A wildlife veterinarian for the Tennessee Wildlife Resource Agency, Grove grew up in Knoxville and did a stint as a wildlife veterinarian in North Dakota; he says he still has a knot of scar tissue on his chest after he fell off a pile of dead moose and onto a rack of deer antlers while working in a cold storage unit. “As a veterinarian, you go into veterinary medicine to help animals,” he said. What the public may not always understand, he continued, is that sometimes killing individual animals is necessary to allow the population as a whole to thrive. “I hate to say it that way,” he said. “But the reality is [that] wildlife management relies on population management.”

As he spoke, the necropsy team moved on from coyotes to raccoons — most of them plump specimens from Iowa, caught in loops of cable that cinch around an animal’s neck or midriff and hold it still. Beneath the skin, the cords had left faint furrows in some animals’ thick white fat.

While there’s currently little market for raccoon fur, there’s demand for trapping them. The animals can carry rabies, and, due to the decline of many of their natural predators, their population has exploded across North America. Unchecked, raccoon numbers sometimes boom and bust: big population peaks, followed by viral epidemics and waves of raccoon death. They’re considered pests by many people, and wildlife managers say they rely on trappers, in part, to keep raccoon numbers from climbing too fast. In the 2018-2019 season, licensed trappers killed more than 647,000 raccoons, according to data from the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, making them the most-trapped species of furbearer in the U.S.

Grove gestured toward a raccoon lying on the necropsy table, its skin cut away from the fatty flesh and pulled up over its head, like an inverted dress. “This individual, to me, represents what’s going to happen to the next 50 animals that get trapped with this trap. And so that’s what I’m concerned about,” he said. “Yes, we have sacrificed this one individual, but we may have just saved 300 individuals that may have been injured by that trap.”

Not everyone agrees that widespread trapping is essential for population control. Some scientists and advocates dispute that coyote-killing programs are actually effective at keeping their numbers down. Thomas Serfass, an otter researcher at Frostburg State University, in Maryland, argued that furbearer biologists sometimes understate the natural checks and balances that limit wildlife populations — and sometimes overstate the harm that animals cause, in order, he said, to promote trapping. “My biggest concern is portraying the animal as a natural resource, as a nuisance, to justify an activity,” Serfass said.

Serfass and other researchers also doubt that programs like the BMPs are the best way to assess the experience of animals in traps. Some of their concerns revolve around the programs’ focus on physical injury, rather than other forms of suffering. “Injury is an important thing, and it does give you useful information, but it’s far from being the only thing,” said Donald Broom, the Cambridge animal behavior researcher who participated in the ISO process. The vulnerability and exposure of being in a trap, Broom said, could actually exceed the physical harm. “If you’re extremely frightened,” he said, “that’s in general worse than being somewhat injured.”

As a result, Broom said, “If you try to do everything in terms of how much injury, then you would miss some of the important things.” Existing traps standards, he said, were written in the 1990s and largely overlooked other ways that traps may cause harm. “We now do know much more about the diverse ways in which suffering can occur, than was known when the standards were first being written,” Broom said.

Other researchers argue that the standards don’t even go far enough to prevent physical injuries. Chief among those critics is Gilbert Proulx, the French-Canadian trap researcher who used to run Canada’s trap research program. Proulx grew up in the Laurentian Mountains of Quebec, the son and grandson of butchers. The family raised pigs and rabbits, and they ran a slaughterhouse. By age 6, he recalled, he was helping debone carcasses on the shop floor.

Proulx loved animals. As a child, he live-trapped red squirrels and chipmunks, constructing his own devices out of wooden boxes. He didn’t want to kill the creatures; he wanted to see them up close. Even then, he knew he wanted to study wildlife for his career. In 1985, 31 years old and equipped with a Ph.D. in zoology, Proulx was asked to lead Canada’s fledgling humane trap research program.

French-Canadian trap researcher Gilbert Proulx now staunchly criticizes existing traps standards, arguing that they’ve done little to protect animal welfare.

Visual: Courtesy of Gilbert Proulx

Working from a facility in Vegreville, Alberta, about 60 miles east of Edmonton on the Canadian Prairies, Proulx and a small group of colleagues employed a three-stage protocol to test killing traps. One paper from that time, testing the Conibear 120 body-gripping trap on pine marten, lays out their methods: In the first stage of the study, Proulx and two colleagues filmed live marten triggering Conibear traps, which had been modified so that they did not close completely. The animals could escape unharmed, and the researchers could analyze the footage to project where, exactly, the metal bar of the Conibear would have struck. The data gave them confidence that the trap would reliably strike marten in the head or neck region, raising the likelihood of a quick kill.

A few weeks later, the team sedated six marten with ketamine, stuck each animal’s head into the trap, triggered it, and timed how long it took the trap-whacked marten to become irreversibly unconscious. Then, finally, they placed the trap in enclosures with fully alert, mobile martens. When an animal would trigger the trap, a technician would sprint over to the enclosure and time how long the animal took to lose consciousness.

Proulx tested traps on raccoon and mink. He ran red foxes through spring-loaded snares, and tried to modify devices to kill more quickly and reliably. “We truly had a top-notch research team,” Proulx recalled. “We were not in the business to pass traps at all costs. But if they were good, we certainly wanted the world to know about it.” (Today, trap testing programs in New Zealand and Sweden use similar protocols to rate killing traps, and a research team convened by the German government recently proposed applying it to rat and mouse traps.)

In his papers from those days, Proulx vigorously defended trapping as an important source of income for thousands of Canadians, and as a tradition for the regions’ First Nations. But his relationship with his supervisors, Proulx said, soon soured. “There was a lot of political lobbying, a lot of interference,” he said, and he felt pressure to approve traps that he thought were unacceptable. In 1993, he left the program and became an independent researcher. By 1999, when Canada ratified the AIHTS, he had grown skeptical of the whole scene, and he felt the treaty set its standards too low. “As researchers, we thought that the people behind those standards and those research programs, they were concerned truly with animal welfare,” he said. “But it turned out they were concerned with saving a trade, which is the fur trade.”

Shortly after ratifying the AIHTS, Canada replaced its system for testing kill traps with computer models. Today, according to Pierre Canac-Marquis, a Quebecois trapper and biologist who has run Canada’s program for the past 26 years, they don’t use any animals at all in lethal trap testing: Technicians gather data on the mechanical properties of each trap, and then enter that into the computer, which runs 10,000 simulated strikes to predict how often the trap will kill its target quickly. “The results are so accurate that they’re even better than if you do a compound testing with live animals,” Canac-Marquis said, comparing the computer models to the kind of testing Proulx used to undertake.

Proulx — along with Warburton, in New Zealand — say those computer models can’t actually account for the idiosyncrasies of animal behavior. “They claim that they can test traps just by looking at the trap on the computer, which I know doesn’t work,” Proulx said. He also has little respect for the BMPs, although he agrees with the general process. The program should set higher standards for traps, he said — and U.S. regulations should mandate that trappers check their traps more frequently. If “you go on the sidewalk and you kick a dog, someone will report you to the cops, you will be arrested, you will be charged with animal cruelty,” said Proulx. “But a trapper can let an animal suffer for 12 hours in a snare or a trap, and it’s okay.”

Today, Proulx runs Alpha Wildlife Research and Management, an independent research firm in Alberta. He still traps, and he still sees himself as a supporter of trapping. But he has grown increasingly vocal with his concerns. The critique of the AIHTS he published in 2020, along with Serfass and two other collaborators, calls for a committee of experts to produce a new, more comprehensive, and more rigorous set of trapping standards. Among other things, they say those standards should extend to more species, set stricter time-to-unconsciousness limits for lethal traps, and include protocols for how to kill animals caught alive. Proulx told Undark he’s already working on drafting the document. The virtual conference he held in November — which included presentations from Broom and researchers from Europe, and which received sponsorship from a conservation nonprofit and a humane trapping organization — aimed to help lay the groundwork for that push.

Not everyone thinks Proulx’s recommendations are especially realistic. “It’s good at some point to have someone pushing from the outside,” said Canac-Marquis, but, he said, Proulx sometimes goes too far. (Rather than describing a dispute over principles, Canac-Marquis also suggested that Proulx’s refusal to cooperate with other stakeholders precipitated his departure from the Canadian trap testing program.) Warburton, who helped develop a respected trap research program in New Zealand, was asked to join Proulx as an author on the AIHTS-skeptical paper. He ultimately declined. “Science is one thing to inform decisions, but there’s economics, there’s practicality, and there’s politics,” he said. “I just felt it was not really being realistic.” (During a conversation in June, Warburton stressed that he had not read the final paper.)

Alongside the scientific dispute, Proulx raises one other concern: The programs in the U.S. and Canada don’t change trapping much on the ground. The U.S. program, he said, “is just a friendly recommendation.” In Canada, where traps must pass to be used legally, he said, regulators never actually check traplines. “Nobody enforces it, so the end result is the same in both cases: These animals suffer unnecessarily.” (Canac-Marquis disputed Proulx’s claims and said that Canadian conservation officers do enforce the use of certified traps.)

It’s not always clear that the BMPs have much influence on trappers. Manufacturers rarely, if ever, advertise that their traps have met BMP standards. In 2015, the fish and wildlife agency association commissioned a survey of more than 6,500 U.S. trappers, asking them about the tools they used, the animals they caught, and the frequency with which they trapped. At that point, the BMP program was nearly 20 years old. But only 42 percent of the trappers surveyed had even heard of it. Of those, only two-thirds said they were guided by the Best Management Practices. Taken together, those numbers suggest that fewer than one in three U.S. trappers deliberately follows BMP guidance in selecting traps. “What does that say about BMPs, and about [the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies], and about this whole very expensive process that took years to put in place?” asked Camilla Fox, the coyote advocate. “To me, there’s the two huge issues, which is, one, the inadequacy of the standards themselves, and, two, a complete failed process of any kind of real adoption of these very base standards.”

White said the program plans more outreach in the future, including a new series of educational videos and more publicity through manufacturers. But, he said, such figures also belie the extent to which trappers use approved devices, whether or not they know about the program. “Most of the animals being captured in the U.S. — somewhere around 80 percent — are being captured in BMP traps,” he said. He also contested that the welfare standard was too low. It had been set, White said, by veterinarians, and the American Association of Wildlife Veterinarians supports the program.

He and other trap researchers, in both Canada and the U.S., say trapping has become more humane since they began their work. And, as White and other BMP researchers note, academic scientists and government trappers are sometimes required to use BMP-certified traps. Today, among the traps recommended under the BMP program is Duffer’s Dog Proof Raccoon Trap, a metal cube with a 1.5-inch hole in one face, which retails for around $20; when the raccoon sticks its paw inside, the trap catches and holds it there, preventing the animal from leaving, and also from chewing its own paw. For beaver, the program recommends suitcase traps — large, folding cages, which can retail for as much as $600, that catch the rodents alive — as well as sets that hold beavers underwater to drown. And, for wolves, one approved trap is a larger version of the device used to catch the Sonoran coyote — the Minnesota Brand 750 Alaskan offset, a $35 foothold device with laminated jaws that spread the trap’s clamping force over a large surface area.

The National Trappers Association has expressed some support for the program. Still, winning compliance from individual trappers can offer challenges. One volunteer at the BMP necropsy event was Jonathan Gilbert, a biologist for the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, a consortium of 11 Ojibwe tribes. (Gilbert, who is White, is not himself a tribal member.) “We can do all the science we want, but unless we get people to use the traps that we’re approving, it’s all for naught,” Gilbert said. As part of his job, Gilbert runs trapper education for the tribes, and he speaks about BMPs. Trappers want to use less injurious devices, he said. But a trapline may require dozens of traps, and replacing old traps with BMP-approved equipment can be prohibitively expensive. For Native trappers, the tradition matters, too. Gilbert said people will tell him, “My grandad gave me, you know, 50 traps, and that’s what I want to use, is my grandad’s traps.”

Brady, the Wisconsin trapper, has heard similar complaints from older White trappers — but, he said, the BMPs are having an effect. “Some of the older generation trappers, they still don’t want nothing to do with it, simply because they got to change all their traps,” he said. “The younger ones are more likely to accept it.”

For years, it has been clear that humane trap research and international agreements alone cannot save the fur market. Sometimes, trappers and their allies characterize the backlash less as a moral or scientific debate, and more as a class dispute — one that pits affluent, urban animal rights advocates against the more rural, working-class people who trap and hunt. “I can’t find the words to fight back,” Zacharias Kunuk, an Inuit seal hunter, told The New York Times in 2003, describing attacks on the fur trade. “They are a bunch of Hollywood rich people who talk as if animals think like humans, when they don’t.”

The last few years have been especially hard for North American trappers. According to Groenewold, the wild fur buyer, the market for one-time mainstays like raccoon and muskrat is one-tenth the size it was a decade ago. A beaver pelt that would have sold for $25, he said, may now fetch $5. The problem rests with demand: “North America and Europe use almost no fur,” Groenewold said.

Groenewold’s business celebrated its 100th birthday last year. But he sounded pessimistic about the future — and uncertain that programs like the BMPs, which have been integrated into trapping public relations strategies for years, actually do much to convince people. “We’re never going to please a person who believes that no animal should ever be killed,” he said, arguing that advocates should instead try to appeal to environmentally conscious consumers in search of natural, biodegradable, climate-friendly clothing.

For now, at least, the decline continues. In 2019, North American Fur Auctions, filed for creditor protection in Ontario, under an arrangement akin to Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the U.S. A direct descendant of the storied Hudson’s Bay Company, the historic auction house had struggled to deal with declining fur prices and, one source said, chronic mismanagement. “It was a hard shocker,” said Brady, who said he spent more than a decade working in trapper relations for the company. “It ripped my heart out. My passion is fur.” He and hundreds of colleagues, he said, lost their jobs. Few, if any, trappers now make significant income from fur sales, although some still make a living as pest control specialists.

Legislatures in several states have also moved to put further restrictions on trapping. In April 2021, New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham signed a law forbidding trapping on public lands. The decision alarmed trapping advocates, who sometimes describe themselves as part of an embattled, misunderstood minority. “Other groups, cultures, and races are prevailing in their quest for what they want because they are sticking together and showing unity,” National Trappers Association president John Daniel wrote in a letter to the membership in March, shortly before the New Mexico legislature passed the bill. “The trappers of New Mexico are on the brink of losing trapping,” he warned. “I sat and listened to our side present the better, stronger, more scientifically correct evidence, but the Committee majority had already been convinced, or in some case spent the time getting elected just to beat trapping.”

During the legislative dispute in New Mexico, opponents of trapping invoked the BMPs as an example of why they consider trapping to be inhumane. The BMP guidelines, wildlife biologist Robert Harrison wrote in an email to Undark, “allow for what I consider to be an unacceptable rate of serious or severe injuries to trapped animals.” Harrison, who was, until recently, a researcher at the University of New Mexico, supported the bill. “In my testimonies at legislative hearings and in other reports, I used the BMP guidelines as an example of the injury rates that trappers consider acceptable,” he added in his email.

Mary Katherine Ray, a retired teacher living in rural Socorro County, began organizing against trapping on public lands 18 years ago, after a trap nearly caught her dog. Programs like the BMPs, in her view, are intended “to pull the wool over everybody’s eyes,” by making trapping seem humane, rather than actually generate sound research. Asked about the traditional elements of trapping, she sounded skeptical. “There’s a lot of things that are tradition that are horrible,” she said, mentioning genocide, slavery, and polygamy. “Times change.”

Recently, some advocates have cited the BMP process in legal disputes. In 2019, The Fur-Bearers and other animal rights organizations filed a Federal Trade Commission complaint against the company Canada Goose, which trims its high-end jackets with wild-caught coyote fur. The complaint argued that Canada Goose had misled consumers by describing the use of BMP- and AIHTS-compliant traps as an example of “ethical sourcing.”

“These standards themselves,” the complaint reads, “permit a range of cruel practices that reasonable consumers would perceive as ‘neglect’ and ‘undue harm’ — not as ‘humane’ or ‘ethical.’” The action didn’t go anywhere, but in November 2020, the law firm behind the FTC complaint tried again, filing a class action suit against Canada Goose along similar grounds.

The lawsuit is still working its way through the courts. But the point may soon be moot. In June, Canada Goose, once a major buyer of wild North American fur, announced it will stop using new fur in any of its products.

To catch a beaver in the state of New York, most people would need to take an 8-hour long trapper education course, obtain a trapping license, select and set the trap in line with extensive regulations, and check the trap every 24 to 48 hours. To catch another sizeable rodent, the Norway rat, however, a New Yorker can go to the hardware store around the corner and purchase a glue board. The sticky square holds the animal until it dies from starvation, thirst, or exposure — or thrashes so hard that it suffocates itself in the sticky glue. Manufacturers suggest that, instead of ending the rodent’s life more quickly, users simply put the trap and the animal in the trash.

Glue boards are banned in some countries. The YouTube mouse trap reviewer Shawn Woods, who routinely kills animals on camera for millions of viewers, has described them as “just horrible.” But glue boards are almost entirely unregulated in the U.S. (Two major manufacturers, Tomcat and Catchmaster, did not respond to repeated questions about the traps’ humane impacts.)

Meanwhile, some 11 million pigs are slaughtered in the U.S. each month. Worldwide, egg farmers kill around 7 billion newborn chicks per year, often by gassing them or grinding them up in mechanical shredders. One animal rights group estimates that humans annually kill between 1 and 3 trillion fish. For all the public attention that furbearer trapping brings, its impact — on a few million animals per year in the U.S. — can seem relatively minor compared with other kinds of animal killing.

All of this can highlight what the psychologist Hal Herzog, in his 2010 book “Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat,” calls “the flagrant moral incoherence” of our culture’s treatment of animals. In an interview with Undark, Herzog recalled working at a university where some mice had escaped from the laboratories. “Mice in the lab had to go through all this rigamarole,” he said, referring to extensive protocols that govern the treatment of experimental animals, down to the precise minimum size of their enclosures and humidity in their air. Outside the lab, maintenance staff were catching them with glueboards. “They were animals that had been the good mice in the labs initially,” Herzog recalled.

In conversations about the ethics of trapping, trappers may invoke things like the Best Management Practices and animal welfare research — but they’re likelier to talk about the baseline brutality of the natural world, and to reflect on the inevitability of suffering. “Just think in terms of a coyote or a bobcat catching a rabbit and tearing it apart while it’s still alive,” said Jeremiah Wood, who runs traplines in northern Maine and founded the trapping website and podcast Trapping Today. “In a lot of ways, I feel as though what we’re doing, relative to what might be the way Mother Nature is, is very minimal.”

At the necropsy event, one of the skinners was Jenna Malinowski, a young Wisconsin state biologist and trapping advocate. Malinowski began trapping with her then-boyfriend (now husband) 10 years ago, while they were living in Idaho. She soon became adept, and today she traps regularly on the flowages around Mercer, Wisconsin, in the far northern part of the state. Recently, she launched a trapping camp for women interested in the sport.

Concerned about the environmental impacts of animal agriculture, Malinowski cut back on meat long ago. “I was vegetarian for seven years,” she said as she skinned a gray fox, slicing carefully through the connective tissue of its hind leg. Eventually, she decided to begin eating game she had hunted and trapped — first venison, but then beaver and muskrat and even, once, a bobcat. Malinowski can’t bring herself to eat raccoon regularly (“it’s too greasy”) but describes beaver as her favorite meal. “It’s local,” she said. “I know the water bodies that it comes out of, too.”

Malinowski finds killing difficult. But, she said, she’s also seen the brutal lives and deaths of wild animals. “Even if their population is low and they do have a natural death, it’s never going to be as quick and easy as using a BMP-approved trap, with dispatching approved by the veterinarian association,” she said.

With trapped animals, she said, “our animals get to be free their entire life. And then they have one bad day, which they would in the wild anyways.” But, she added, “Those farm-raised animals, their entire life sucks.” Today, other than game, Malinowski occasionally eats organic chickens that are raised in a backyard by friends. Other than that, she still avoids farmed meat.

For now, the Best Management Practices program continues. This summer, the necropsies will take place down in Madison, Wisconsin’s capital. White already has trappers in several states working to catch bobcats, gray fox, swift fox, more coyotes. This season, he is testing a high-tech trap that slings a loop of buried cable around a coyote’s neck. In September 2021, he said he was still going through the data from that year, but he had tallied up the trauma scores. All the traps did well, he said. They all seem like they will pass. In November, White confirmed it: All the traps had passed.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Research is very important to myself being a trapper for 52years .The more science based data we have the better us Trappers will be in the field

I really appreciated the deep history and perspectives explored here. I find myself somewhere in the middle; animal suffering should be limited as much as possible, but there are reasons to trap. Harvesting meat seems like the strongest, and I’m left thinking about whether collecting fur is sufficient. Jenna Malinowski’s perspective at the end resonated with me.

Sometimes an animal will chew it’s foot off to escape. What horrors humans commit so willfully and blindly. They simply don’t care.

When animals are held to the same standards of accountability as humans, I will support animal rights.

As for trapping, killing beavers this way cost my community around a few thousand per year. Without trapping, we’d spend $100K per year rebuilding the roads these rodents damage with their burrowing activities. Further, we keep homes and cropland from flooding.

Y’all pick. You want good roads and food or do you want critters like beavers, wild hogs, nutria? Do you want to sit outside without worry of being attacked by rabid coons, foxes, yotes, bobcats and skunks or do you want to allow these critters to breed (pre-infection) and dine on your pets, then get infected and spread the contagion?

People that trap animals aren’t either experts or researchers. They’e sadists and murderers. Mother Earth isn’t a biological niche for human beings.

Tim,

Thank you. We’ve seen an explosion of public sadism in recent years, such as children, even infants, being taken from their parents at the US southern border. They will be forever traumatized. VP Pence said, speaking for The Former Guy, said “cruelty is the point.” I