It is generally best to reject out of hand any conspiracy theory that assumes more than three people have kept something secret. Which may be why a large fraction of the biomedical community rejects the suggestion that a lab leak out of the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) could have been the source of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that has caused the Covid-19 pandemic.

But the lab-leak hypothesis is not a typical conspiracy theory; the very circumstances of the event and its extraordinary location near the WIV give it prima facie support. Because the world of viruses, bats, and pandemic infection is intrinsically strange to most people, how about if I explain this with an analogy?

Let’s say, for instance that a Florida panther rampaged through the South Bronx, injuring many people. It would be immediately reasonable to wonder: How could that possibly happen? Florida panthers don’t live anywhere near the Bronx and aren’t normally so ferocious.

Concern might be further increased if local officials — who have authority over the zoo — attempted to hide or mischaracterize the initial rampage, or tried to claim that the rampage had occurred in a completely different country. Why would they do that if there was nothing to hide?

Obviously, zoo officials would be concerned that they would be blamed. If they were confident the Florida panther wasn’t theirs, the logical path forward would be to hold an immediate press conference and invite a blue-ribbon committee to come as soon as possible to thoroughly inspect the zoo. That committee might determine that all panthers were accounted for, and that no breeding program could account for additional cats.

If zoo officials did just the opposite — if they engaged in a ham-handed refusal to allow an immediate and independent investigation — the logical conclusion would be that it was even more likely the panther had come from that institution.

“But wait,” zoo officials could say. “While we do have Florida panthers here, the one that rampaged the city had a genetic makeup different from the ones we house.”

OK, that would be a persuasive argument.

That is, unless additional investigation revealed that the zoo had a breeding program intended to develop more fearsome Florida panthers. And that the genetic makeup of the panther in question was actually pretty similar to ones the zoo housed.

At that point, the zoo would likely have to relent and allow an outside group of investigators in for an inspection. However, it would not be reassuring if the zookeepers stipulated that the composition of the investigation team would be controlled by the same local officials who had initially tried to cover up the rampage. It would be even worse if the local officials delayed the inspection for almost a year — more than enough time to change all the locks and edit the breeding books.

With the situation spiraling out of control, the zoo might make a final public relations argument. “But wait,” they might say. “We just checked and this is not a completely different type of panther; it’s similar to those crossbred with Texas cougars. We didn’t breed it here. It must have bred naturally.” This would be a strong argument, were it not for the fact that the zoo had been sending collecting parties to Florida and Texas for years.

If it then turned out that a special delegation had visited the zoo two years before the panther rampage and reported concerns that there were inadequate safety provisions that could lead to a panther escape, at that point even skeptical people might be persuaded that this wasn’t just an all-smoke-no-fire situation.

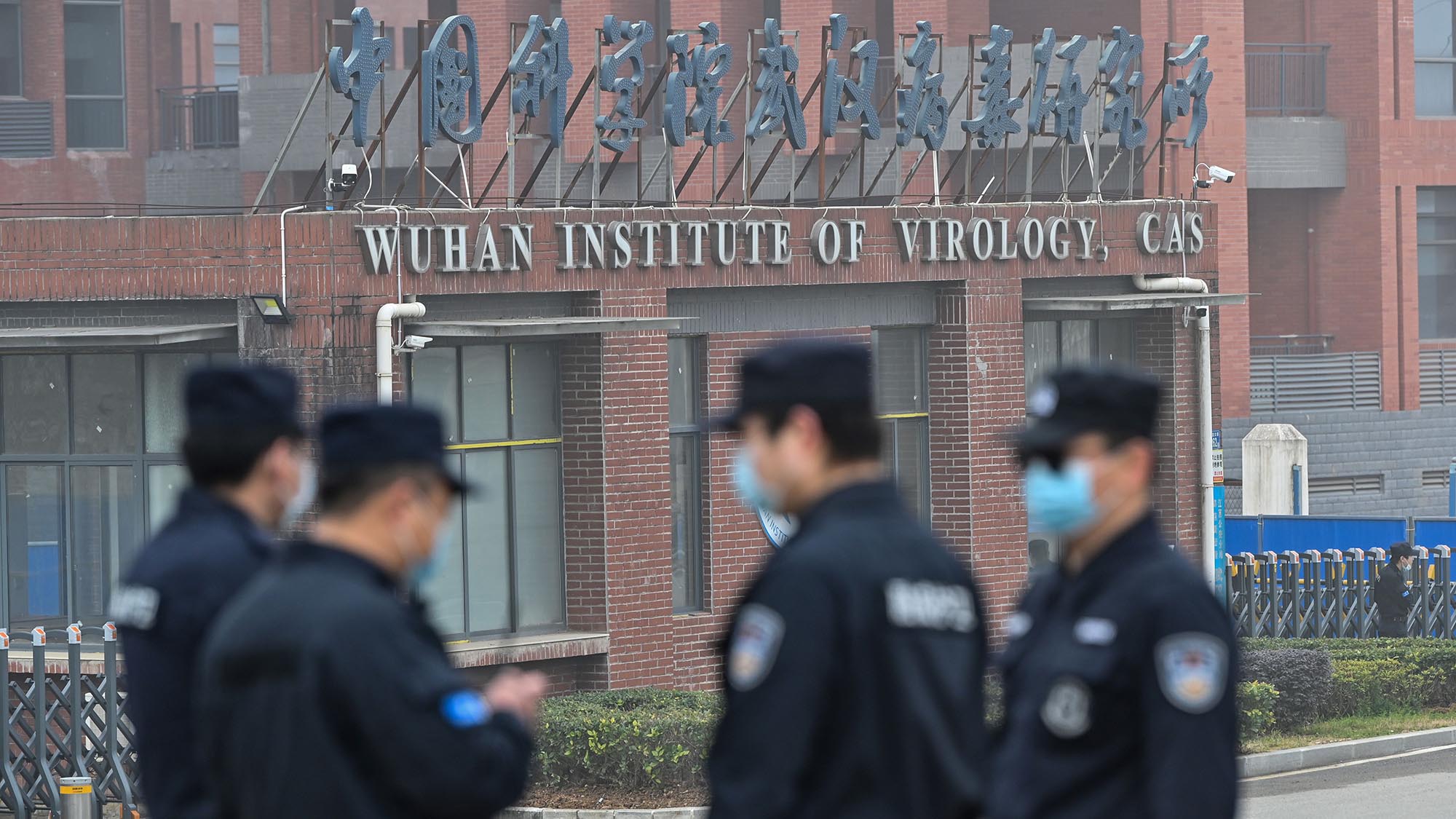

Every analogy has its limits, of course, but this one is grounded in reality and an extraordinary set of coincidences. The WIV is around 10 miles from the site of the initial outbreak in Wuhan, whereas the natural coronavirus variants that most closely resemble SARS-CoV-2 come from a region in South West China more than 900 miles away. The WIV runs the world’s leading effort geared toward collecting wild coronaviruses from that region, and they are reported to have tinkered with the wild viruses to develop potent new strains. Two years before the onset of the pandemic, U.S. diplomatic scientists visited WIV and sent back strongly worded reports to the State Department warning of inadequate safety conditions. And when a delegation from the World Health Organization visited the institute earlier this year, Wuhan officials limited the team’s makeup and restricted their access.

| For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive. |

Although it is possible that we will someday sort this out, it is unlikely. The only way to do that, now that the Institute itself may have been scrubbed, would be to escort all of the involved WIV officials and their families safely out of China so that they can be interviewed in a setting where they can speak freely. That’s not going to happen.

But there is one thing that I believe we can assert definitively: The statement by a WHO official that “it was very unlikely that anything could escape from such a place” is wrong to a profound degree. It doesn’t take a human factors expert to understand that asking people to work with dangerous materials as part of their day-to-day routine for years at a time makes a safety lapse almost inevitable. Policies governing institutes like WIV should be designed with Murphy’s Law as an inescapable truth, not an afterthought.

All that said, it is still pretty likely that Covid-19 was a spillover event from nature, and we should be humbled that it didn’t kill nearly everyone. But we also shouldn’t dismiss the possibility of a lab leak as mere conspiracy theory. Clearly, our estimates of risk were catastrophically wrong, as we had been warned many times. We need to separate ourselves from the natural reservoirs of novel infectious diseases to the greatest extent possible.

Dr. Norman Paradis is a professor of medicine at Dartmouth College.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

This is getting old. As old as it was 16 months ago…. jfc it’s been that long already…

1. It’s irrelevant if an infected animal in a lab went to a wet market, or an infected animal in a forest went to a wet market. The result is the exact same and the causes are very similar amounts of recklessness.

2. Fairly close cousins have been found in nature. The issue isn’t that the lab was studying these cousins (which they should, China bore the majority of the damage from MERS and SARS-1). The issue is that we don’t study them enough. There are thousands, millions perhaps, of Coronavirus strains mutating everyday in the wild. And we only know a tiny fraction of them, because animal viruses aren’t a well funded or popular field. And mostly focused on farm animals.

3. Yes, all labs globally should be better. And they probably all have changed, worldwide. The CCP is going to crack down harder than anyone since the entire fiasco seriously damaged China’s reputation and economy. Already suffering from Xinjiang and Hong Kong political problems from 2019. China has a huge victim complex, has a culture of secrecy, and of course ain’t gonna trust any outsiders to do full investigations and make them lose even more face.

But the theory does not need to be true for any of the labs worldwide to improve. It’s already happened.

So again, it doesn’t matter.

Sure, it’d be nice to know for 100% certain, but science and info leaks move super slowly. Medical knowledge has advanced more in 1 year than it has in the last 5. Give it 3 more years, and we’ll probably find “the missing link”.

True: We don’t have the facts to decide for either hypothesis, and yes, the Wuhan Institute of Virology looks like a suitable culprit. However, we do know for a fact that zoonotic viral infections have occurred multiple times in the past – including the previous two Coronaviruses (SARS, MERS), and are all but certain to occur again in the future. We also have strong indications [Emergence of genomic diversity and recurrent mutations in SARS-CoV-2, Lucy van Dorp et al.] that SARS-CoV-2 has been human-hosted as early as October ’19 (two months before it got detected), which is plenty of time for the infection to travel before it spread and became known in Wuhan; therefore, the 900 miles are no strong indication.

It does seem very possible that the virus was identified in Wuhan rather than originating there. It is a crowded port city.

Based on the new data from China and the WHO that tens of thousands of wild animals were sampled with no sign of SARS2-like viruses it is becoming ever more implausible that ‘nature’ was the source and ever more likely that it was some kind of biosafety lapse.

We have also proposed the following series of events:

https://www.independentsciencenews.org/commentaries/a-proposed-origin-for-sars-cov-2-and-the-covid-19-pandemic/

Excellent.

I guess Trump being an early adopter of the theory of a lab problem discredited the idea to the degree no one wanted to pick it up. But that’s obviously irresponsible, if Trump said the Earth circled the Sun we wouldn’t all abandon a heliocentric world view. Glad this doctor had the rationality to approach this question again regardless of politics. There are Level 4 labs all over the world and ignoring the potential global danger of risky or incompetent behavior by their operators is insane. When there’s good reason to think 3 million people may have died this year because of a lab error, we need to pay attention to that.

This article deserves to be widely read. It’s quite brilliant in how it pushes back against those who dismiss the lab-leak hypothesis as a crackpot conspiracy. There is a reasonable possibility that the pandemic started with an accidental leak from a lab that was storing and researching coronaviruses. And there’s also a reasonable possibility it has natural origins. The reference to natural origins at the end of the article is well-judged because the current commonsense position is to keep an open mind and call for investigations of both hypotheses — lab-leak and natural zoonosis.

There were only four known endemic coronaviruses before the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Just four. SARS-CoV-2 will be the fifth. Historically, coronavirus pandemics have been rare. We know for sure that one of two incredibly low probability events happened — lab-leak or natural zoonosis. Which one happened is still to be confirmed. So neither should be dismissed, and both should be investigated.

I was astounded that you ended this discussion with the disclaimer that “it is still pretty likely that Covid-19 was a spillover event from nature.” Considering that the entire thrust of the article was that the first likelihood was a lab leak rather than a natural phenomenon, it smacked of a grand CYA maneuver, as if you feared that having stated the obvious would prove too costly.

I agree. I found this writing compelling and convincing up until that last statement which almost invalidates the whole thing.

Exactly.