Scientific collections housed by museums and other institutions — such as dinosaur fossils in storage boxes, their inked labels, and even 3D scans related to them — are recognized as cultural heritage by modern tradition and international law. Countries that have recently gained or restored independence share a particularly acute feeling of commitment to the heritage embodied in these collections and worry about its fragility.

It is no accident that a colonizing force sometimes tries to steal this heritage through cultural or physical appropriation — in a way of contesting that society’s identity. My fellow researchers and I in Ukraine have heard many stories about statues, pictures, or even mummies taken as war trophies in the past several hundred years, but we did not expect this in the 21st century. Nevertheless, this is precisely what we have witnessed during Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine.

Ukraine is a big country with a long history and centuries-old universities, public libraries, and research centers. Not surprisingly, Ukrainian scientific collections are diverse: They include cultural and natural objects which are permanent and usable in everyday research, as well as live lab cultures and specimens from wild and domesticated plants and animals. Institutions involved in preserving this diverse heritage include museums, libraries, archives, protected areas, universities, and research institutions scattered across the country. Ukrainian researchers have contributed to physics, biology, chemistry, earth and planetary sciences, and archaeology by extensively using existing collections and archives and adding enormous numbers of new items to this rich heritage.

However, decades of economic turmoil and outdated policies eventually led to the erosion of infrastructure and collection management practices. Emergency plans for protecting collections dated back to the Cold War era of Soviet dominance. Policies for digitizing and cataloging them were inconsistent. Training was mostly impractical and mismatched to the new challenges of collection preservation. Most importantly, war itself was not considered by Ukrainian society as even a hypothetical threat 10 years ago, and the probability of an attack by Russia could only be suggested as an absurd scenario. However, this happened, and Russia attacked Ukraine in 2014, invading Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk areas, only to come back in 2022 with a country-wide invasion.

Several independent research efforts have suggested that we are facing an elaborately planned act of cultural genocide.

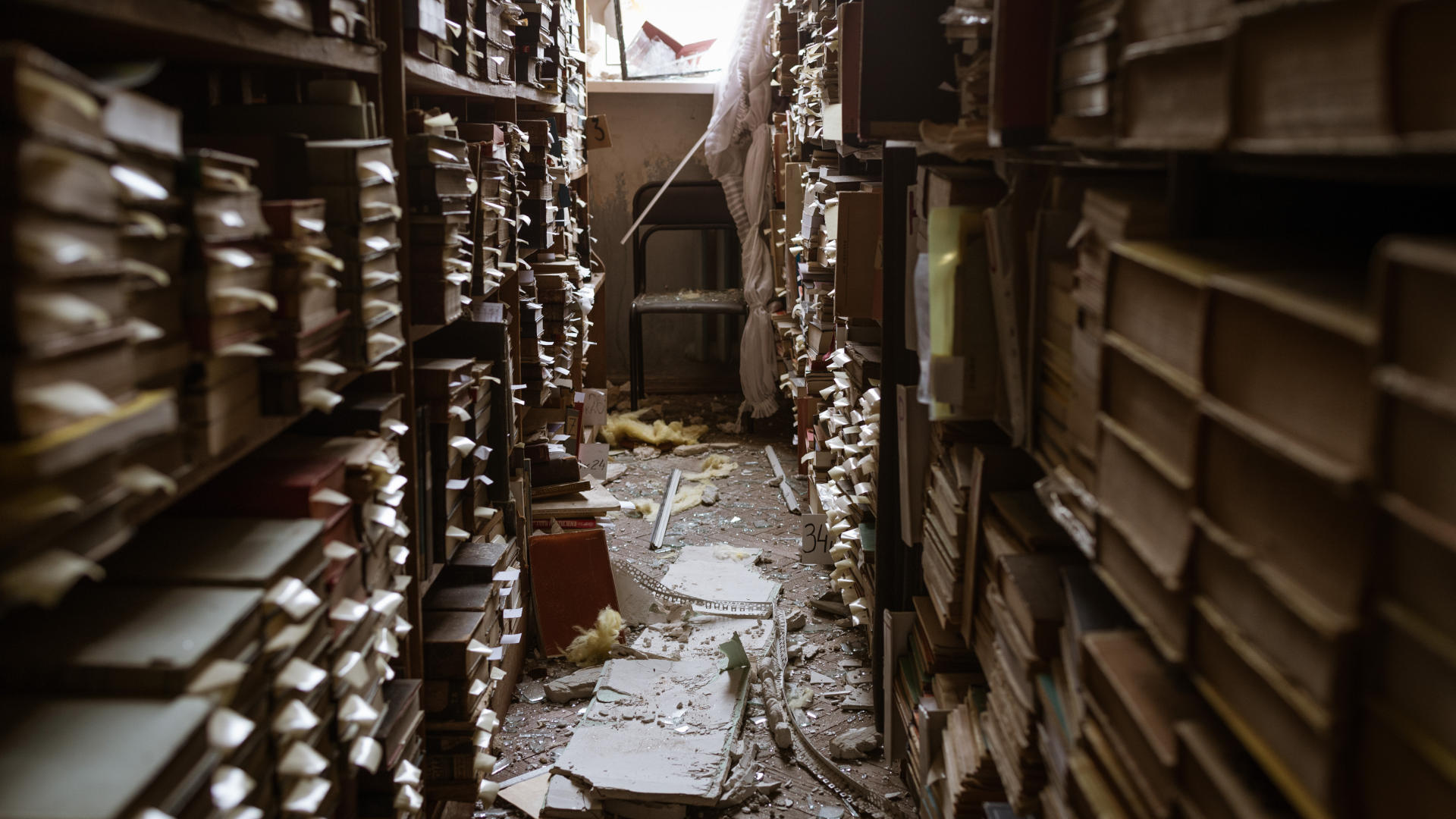

I had the misfortune to experience the 2014 attack as a collection curator at V.I. Vernadsky Taurida National University in Simferopol, Crimea, and I had to leave after it was occupied by the Russian army. And now, under the most recent attack, I was forced to save collections and data archives from bombs and missiles. First, the Russian leaders and intellectuals contested the identity of the Ukrainian nation, claiming it as a part of Russia or, together with Russia, part of a supposed Eurasian civilization. Then Russian soldiers and officials invaded Ukraine and started looting museums, flooding archives, bombing collection-holding institutions with missiles, excavating antiquities, mutilating historical pieces, and worst — kidnapping curators. Several independent research efforts, including a multidisciplinary study by a team of which I am a member, suggested that we are facing an elaborately planned act of cultural genocide.

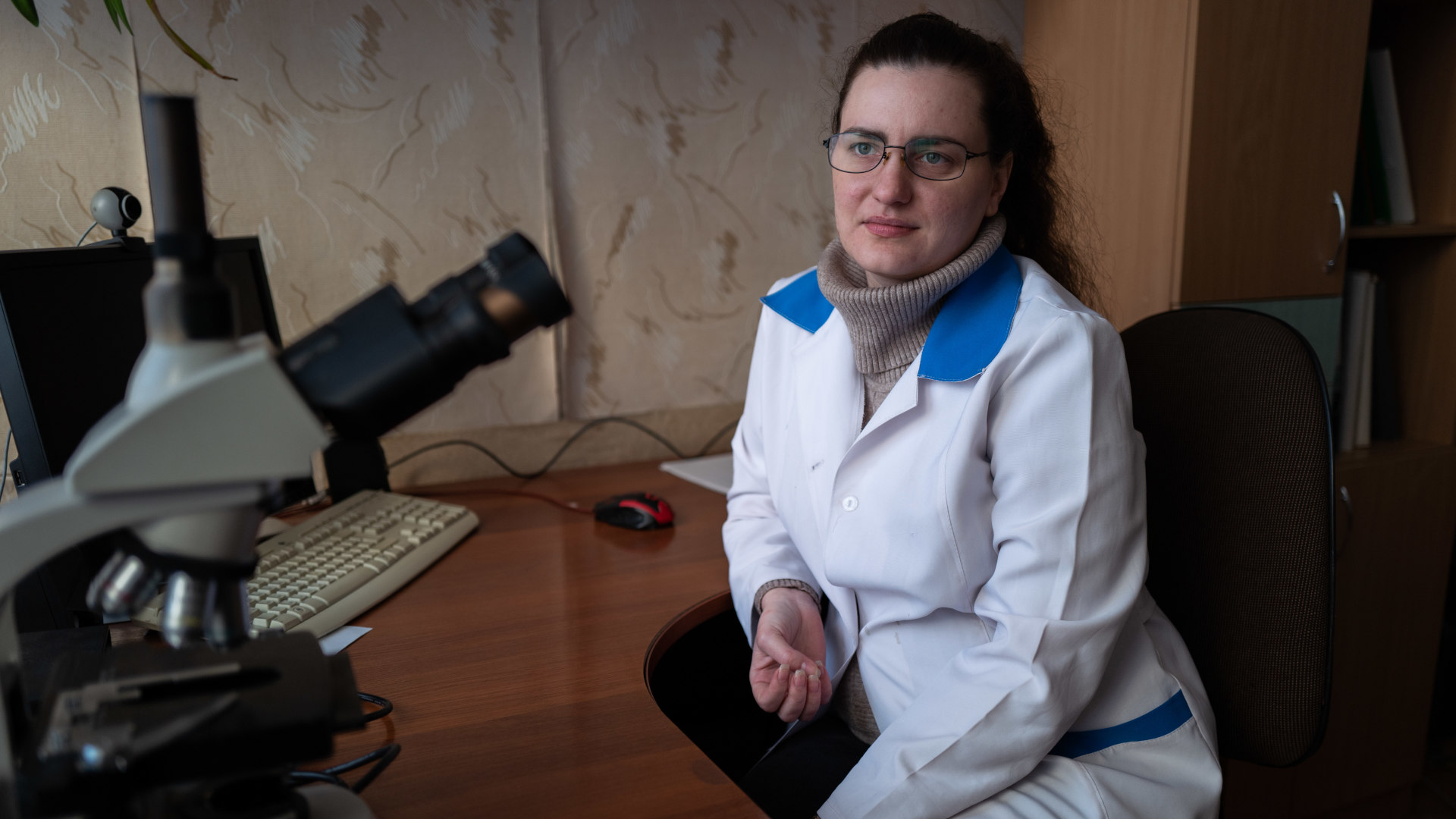

Faced with the Russian army, institutions were struggling to save lives rather than collections. Rescuing collections, either by hiding them in shelters or evacuating them to safer areas of the country, mostly became a personal initiative of directors, curators, researchers, and ordinary citizens. In some institutions, collections were preserved because curators lived in the collection rooms for weeks or months. The civic sector — consisting of numerous grassroots initiatives, nongovernmental organizations, and volunteers — took action across the country, and professional solidarity and support from colleagues abroad were helpful in preserving collections and data and literally saving lives.

Importantly, some of the activities, which had started from the creation of a nation-wide inventory of collections, had been launched in response to the first Russian attack in 2014. Progress made since then in collection management, emergency planning, digitization, and public representation was primarily due to the civic effort. In this way, the primary response of citizens built some capacity, which saved much of Ukrainian society and heritage in 2022.

In a recent white paper for Science at Risk, a project to document and communicate the effects of Russia’s military aggression on Ukrainian science and to suggest preservation and rebuilding action, my colleagues and I made recommendations for how to preserve museum, library, archival, and scientific collections during the war. We based them on interviews with collection managers, curators, researchers, NGO activists, and extensive analytical work previously made by several teams in Ukraine on past global conflicts. For professionals involved in collection management, we recommended cooperating with the authorities in the identification and rescue of collections, documenting losses, defining priority criteria for collection rescue, establishing and sharing safe storage facilities, and using open storage of materials and data, among other recommendations.

Rescuing heritage of all sorts — including scientific ones — is necessary for survival of the society under attack.

For decision-makers from local communities and for funding and development agencies, we suggested making heritage preservation a priority for raising and allocating funds, diversifying forms of support, prioritizing support for in-country collection preservation, and harmonizing legal frameworks and practical implementation as long-term priorities.

Finally, we suggested a brief road map for governments, echoing previous Ukrainian professional discussions on the strategy for saving heritage during war: define heritage preservation as integral to national safety and security policy, create dedicated units for heritage protection and rescue, criminalize attacks against cultural heritage, prepare an international tribunal on responsibility for heritage destruction and restitution, and repatriate inalienable heritage items.

The opinion shared by many members of professional communities who became the witnesses of this war is that heritage and culture as a whole may become a battlefield — not only symbolically, but in a very physical and ruinous way. Heritage can be a direct target of an attacker. Rescuing heritage of all sorts (including scientific ones) in multiple ways and on multiple levels is necessary for survival of the society under attack.

Pavel Gol’din is an expert in marine biology and vertebrate paleontology and a curator of research collections at the I.I. Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.