Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has lasted for more than two years and counting. This assault on the sovereignty of Ukraine and its people continues to disrupt every aspect of civilian life. Much of the war’s damage is plain to see: lives that have been lost, wounds (physical and psychological) that will never fully heal, cultural heritage that has been destroyed. But there are other losses that are harder to keep track of — including some unfolding silently in the shadows of Russia’s military operation. Among them: the large-scale plunder of fossils from Crimea.

In 2018, a cave full of Stone Age fossils was discovered near Zuya village in occupied Crimea. Ever since, scientists affiliated with Russian institutions have been excavating fossils in Taurida Cave, transferring them to Russia, and publishing studies on them. The discoveries include bears, saber-toothed cats, antelopes, and many other animals. Multiple such studies declare that these fossils originated from Crimea in Russia. The Russian Science Foundation supports research in Taurida Cave through a three-year project. Some studies that have European co-authors declare funding by the European Union. But so far, dozens of publications on fossils from Taurida Cave have come out, and none of the papers I reviewed have co-authors affiliated with a Ukrainian institution.

The authors publish in English for an international scientific audience — and in international journals. A significant share of the publications appears in Doklady Biological Sciences. This Russian-based journal is published by Springer Nature, one of the world’s largest academic publishers. Springer’s portfolio also contains other journals that have featured studies on fossils from Crimea, including the Paleontological Journal (another Russian-based journal) and the Journal of Mammalian Evolution.

In addition, Taylor & Francis, another major academic publisher, hosts several journals in which articles on fossils from Taurida Cave have appeared (Historical Biology and the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, for example). The operation of these journals is governed by Taylor & Francis’ editorial policies, which state that the publisher “respects its authors’ decisions regarding the designations of territories in its published material. Taylor & Francis’ policy is to take a neutral stance in relation to territorial disputes or jurisdictional claims in its published content, including in maps and institutional affiliations.”

Dozens of publications on fossils from Taurida Cave have come out, and none of the papers I reviewed have coauthors affiliated with a Ukrainian institution.

Mark Robinson, a media relations manager for Taylor & Francis, said in an email message that authors submitting to any of the publisher’s journals are required to follow its editorial policies and ethical guidelines — including the requirement to follow all relevant laws. “We will look into the issue you raise,” Robinson added, “to see whether there has been any breach of those standards.”

Representatives of Springer Nature did not respond directly to similar questions, but the dynamic seems clear: Russian scientists have thus far been able to excavate fossils from occupied Crimea, and then publish their research in international journals — despite the apparent provenance of these specimens.

Ever since Russia’s assault on Crimea in 2014, the legal status of the peninsula is that of an occupied territory. It still belongs to Ukraine but is “actually placed under the authority of the hostile army,” according to the 1907 Hague Regulations. Consequently, Russia as the occupying power has certain obligations regarding territory which it temporarily controls. For instance, international law prohibits the seizure of enemy property unless required by military necessity. Because a law enacted by Ukraine in 1994 declares the subsoil to be “the exclusive property of the Ukrainian people” and permits geological study only upon authorization, this makes fossils from Taurida Cave enemy property without military use which Russia cannot lawfully appropriate.

Another set of relevant rules is contained in the 1954 Hague Convention. Russia and Ukraine have both ratified the treaty, which requires parties to prohibit, prevent, or put a stop to “any form of theft, pillage or misappropriation” of cultural property. Moreover, the Additional Protocol to the Convention requires states to prevent the export of cultural property from a territory under their occupation. Because Ukrainian law considers fossils as cultural property, Russia thus violates several legal obligations as an occupying power through both the extraction and the export of fossils from Taurida Cave.

Historically, paleontologists have often benefitted from colonial and imperial projects and conducted research in territories under foreign domination. Only in the last few years has the discipline begun to confront legal and ethical issues in their field. A catalyzing controversy surrounding Myanmar amber with fossil inclusions rose to prominence in 2019. This material is scientifically invaluable but comes at a terrible human price as it is mined amidst armed conflict using forced labor. Scientists’ ethical dilemma is clear: Can the insights gathered from studying Myanmar amber justify the contribution it makes to human suffering? Discussions about this question took place in letters to the editor of academic journals, papers, and podcasts.

Russia violates several legal obligations as an occupying power through both the extraction and the export of fossils from Taurida Cave.

In contrast, I have seen no such constructive controversy around these Crimean fossils. The scientific community is silent, and the public is unaware. This is regrettable as many pressing ethical questions require our attention. Consider those Russian scientists who study Crimean fossils: Is what they are doing right? Would it even make a difference if they refused to study specimens from Crimea? Are there any ways for them to mitigate the harm which fossil theft causes? These are fundamental questions of science under authoritarian rule: too wide to be answered here and yet too acute to be ignored by the scientific community.

The same goes for all those involved in the publication of studies on stolen fossils, such as the scientists who judge the quality of such manuscripts in the peer-review procedure and those who, as editors, decide whether an article is published. Should the scientific merit of a manuscript alone inform their decisions? Is it acceptable for them to hide behind editorial policies that allow Vladimir Putin’s neo-imperial project to seep into academic publications? What is their responsibility in light of legal and ethical concerns about research submitted to them for publication?

There is also a more general lesson to be learned: We — individual researchers, journal reviewers and editors, science enthusiasts, visitors to natural history museums — all need to start caring about where a scientific specimen came from. Admittedly, everybody benefits from the knowledge that we gain if any scientist studies a fossil — especially when the results are published in an open access journal.

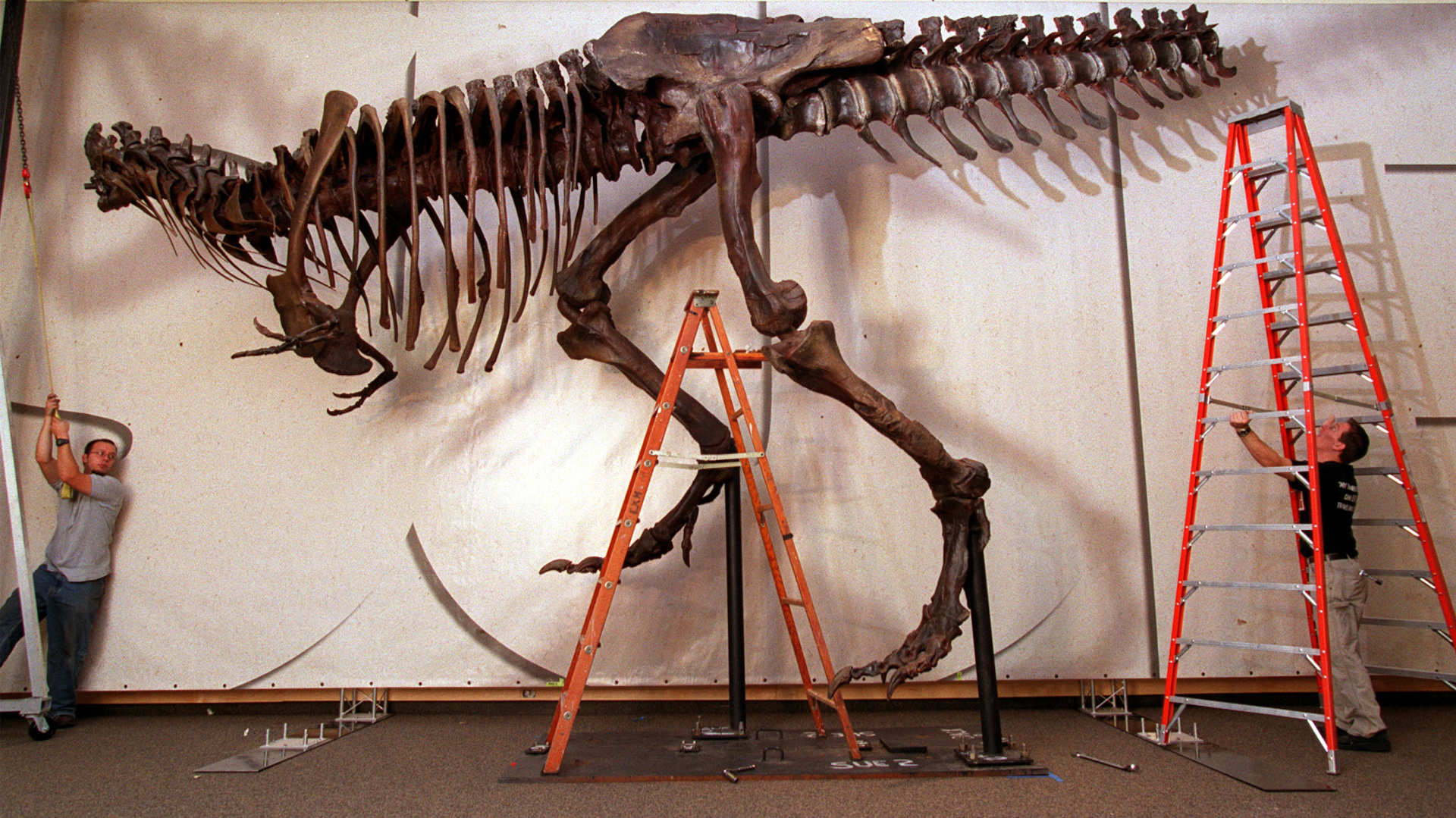

In contrast, the secondary gains from a specimen are often distributed in a highly inequitable manner. For example, those scientists who have the specimen get to publish papers on it. Publications and citations are the de facto currency of academia. Accordingly, this prospect often encourages unethical behavior among researchers. Similarly, charismatic specimens help institutions attract visitors, generate revenue, and promote tourism to a given area when publicly displayed. If fossils are stolen, all these benefits are withheld from researchers and institutions in the country of origin.

For academic publishing, this requires implementing a robust system of provenance declarations. The editorial policies of some publishers such as Nature Portfolio (a division of Springer Nature) or Taylor & Francis already take first steps in that direction. The abundance of publications on Crimean fossils shows, however, that these policies must become more rigorous and comprehensive — and that they must actually be implemented. Whenever scientists submit a study on specimens from abroad, editors should ask them to indicate where and when the materials were collected and when they were exported; present export permits, or demonstrate that no export permits were necessary; and confirm that the extraction and export complied with the applicable domestic and international legislation.

Scientists who have the specimen get to publish papers on it. Publications and citations are the de facto currency of academia. Accordingly, this prospect often encourages unethical behavior among researchers.

Editors must take such provenance declarations seriously: If the submitting authors fail to dispel doubts about whether their study was conducted legally and ethically, such a piece should not be published. Publication pressure is a powerful motivator for scientific misconduct, and editors and reviewers must do better in reducing such incentives. Caring about specimens’ provenance is one such way.

Admittedly, the theft of fossils is not even close to being the worst thing which Russia is doing in Ukraine. But as an issue of scientific ethics that goes widely unappreciated, it still warrants our attention. After all, we are witnessing the plunder of Ukraine’s paleontological heritage. Every fossil that is lost this way is one fewer specimen for Ukrainian graduate students to study and for Ukrainian children to marvel at in museums. And all of this happens through the complicity of individual researchers in a situation of unbearable injustice.

Paul P. Stewens is a legal researcher who specializes in law and paleontology and studies legal issues relating to the extraction, transfer, and ownership of fossils. His research has been featured in Science, The Economist, and a TEDx talk at the Geneva Graduate Institute.