In Ukraine, a Long Road to Rebuild the Scientific Community

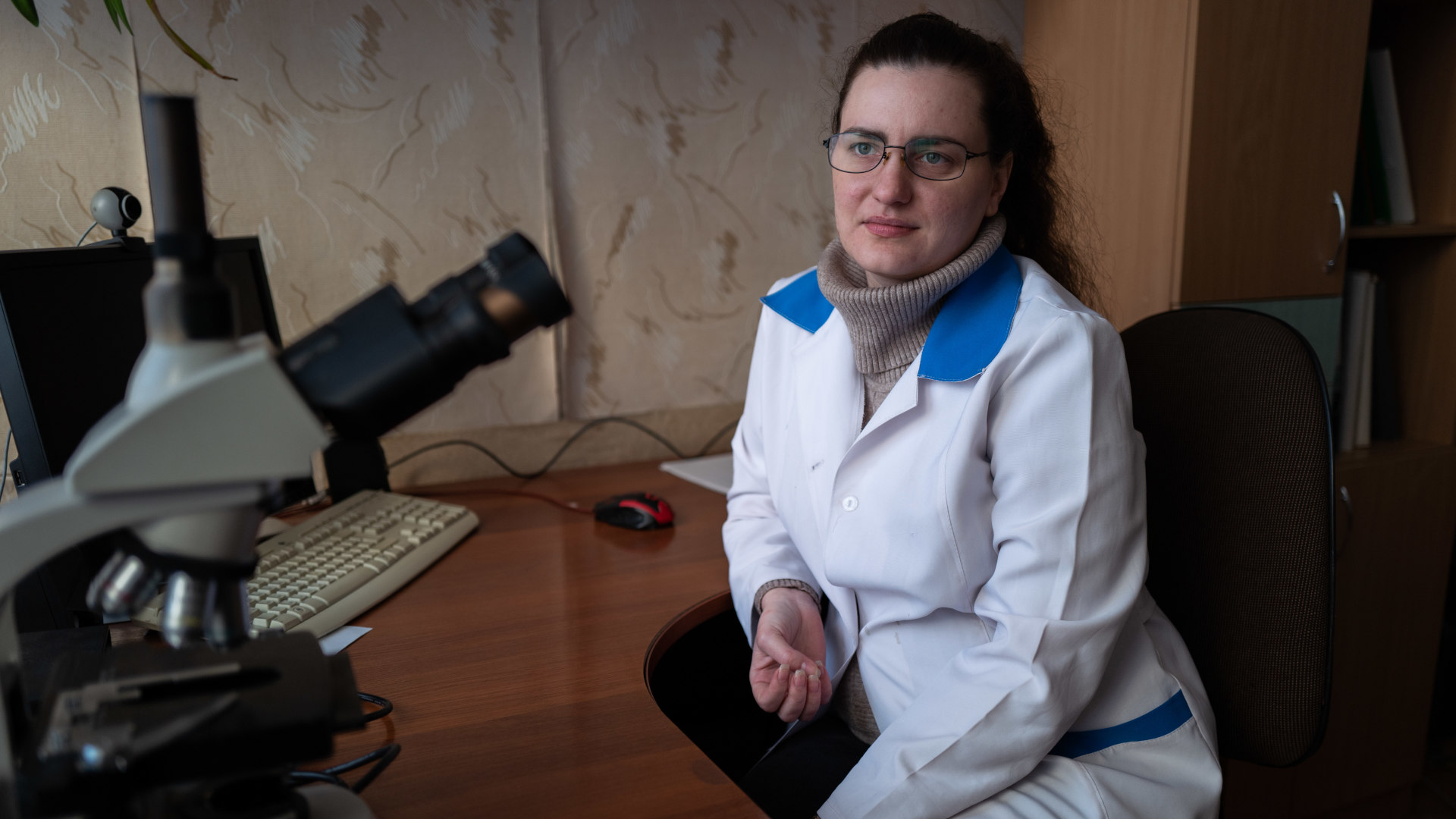

On the morning of Feb. 24, 2022, 32-year-old Yana Hvozdiuk, a scientist in Kharkiv, awoke to the sounds of war. “When I realized what was happening,” she said, “I immediately called my mother.” Hvozdiuk’s mother told her to to pack up her things and come to her house. She then tried to convince her to leave Kharkiv.

Although many other Ukrainians were in fact leaving, Hvozdiuk did not heed the advice. Instead, the researcher decided to continue her work at the Institute for Problems of Cryobiology and Cryomedicine of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, a sprawling complex on Kharkiv’s western outskirts that focuses on the ways in which low temperatures affect living things.

When she first spoke with Undark in January nearly a year after the invasion, Hvozdiuk sat at a desk in her small, spartan second floor office. Under her lab coat, she wore a thick sweater — the building’s heating systems were badly damaged by shelling, and the institute still can’t afford the necessary repairs. She worked remotely writing articles for the first few months of the war and returned to the damaged office in May 2022.

Kharkiv is home to roughly 1.4 million people and is located less than 25 miles from the Russian border. For decades, the city was the heart of Ukranian’s thriving scientific community, home to dozens of national research institutions and the country’s oldest universities. Because of its proximity to the border with Russia, Kharkiv was also one of the hardest-hit cities at the beginning of the Russian invasion. From late Feburary to May 2022, the city endured heavy bombardment from Russian rockets and artillery; today, destroyed and damaged buildings are everywhere and in the central square, a Russian rocket protrudes from the ground, left in place as a memorial.

More than a year after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Kharkiv and other cities are slowly returning to life. Despite this, nearly 6 million Ukrainians remain refugees in Europe as of mid-June, according to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees. In June 2022, in anticipation of what such an exodus could do to the scientific community in Ukraine, a coalition of international scientific academies issued a joint letter outlining a 10-point plan to rebuild the country’s scientific workforce and infrastructure. But so far, for many Ukrainian scientific institutions, enticing their best and brightest to return to a country still at war is proving difficult.

According to internal figures gathered by the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, roughly 15 percent of Ukraine’s scientists have left. In a wartime economy, there is virtually no money to rebuild damaged institutions. And if the young scientists who fled do not return home, Ukraine is at risk of losing an entire generation of talent. If this happens, Hvozdiuk says that recovery will take a very long time.

Hvozdiuk told Undark in follow-up Telegram messages that she thinks she made the right choice to stay in Ukraine, but life in her birth country has not been easy. “I can honestly say that I kindly envied people who were able to leave everything and everyone,” she wrote.

Professor Oleksandr Petrenko is a colleague of Hvoziuk, and the director of the Institute for Problems of Cryobiology and Cryomedicine, where he’s worked for more than 40 years. Sitting in his high-ceilinged office in Kharkiv in January, he said that one of his biggest challenges is retaining young, motivated staff like Hvoziuk.

Petrenko estimates that about 80 percent of young scientists and researchers have left Ukraine since the war started. Of the staff that his own institute lost, some still haven’t come back. Work at the institute hasn’t been restored completely yet, he said.

Many of the scientists who left were able to find positions in nearby countries like Poland at the beginning of the war, often with the assistance of international grants and programs. Now, even though some institutions in Ukraine are reopening, Petrenko said, the scientists who went abroad “prolong these job opportunities” and are not returning.

Because so many young researchers have left, Petrenko added, one of the biggest challenges will be bridging the generational gap. He says that his institute is now focusing on promoting educational programs to entice both new and former students into the fold, despite the low number of students currently in the city. Petrenko aims to make the most of the knowledge and experience of the staff who remain — roughly 120 of whom are eligible to teach — and to ensure that their knowledge is passed on.

Directors like Petrenko face another challenge: funding. An open letter issued by members of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine stated that “all Ukrainian institutions are cut off from international grant programs and the Ukrainian government has considerably cut the science funding programs, thus we can’t allocate money to maintain the design and construction operations, as well as maintenance, replacement or upgrade of our equipment.” Although Petrenko told Undark that he’s now focused on making positions at the institute as attractive as possible, the lack of money makes it difficult to lure people back. In March of 2022, he announced a fundraising effort to help his staff to, among other things, rebuild their homes and continue their scientific projects.

Under normal conditions, Petrenko’s institution relies on government funding not just for scientific programs, but also for maintainence. With the Ukrainian national budget aligned almost entirely with the costs of national defense, there is precious little to spare for the repair of scientific institutions.

But there is plenty of damage in need of attention. On March 6, 2022, for instance, a Russian rocket struck a building that houses a nuclear research reactor at the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, one of Ukraine’s most highly regarded research institutions. The explosion destroyed vital parts of the institute — including a power transformer critical to the reactor’s operation — and necessitated months of painstaking repairs. At the State Scientific Institution “Institute of Single Crystals” of National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in Kharkiv’s academic district, Russian shelling damaged a pharmceutical production facility. And Petrenko’s own institution was hit hard, too, blowing out windows, damaging plumbing and heating systems, and destroying irreplaceable biological samples.

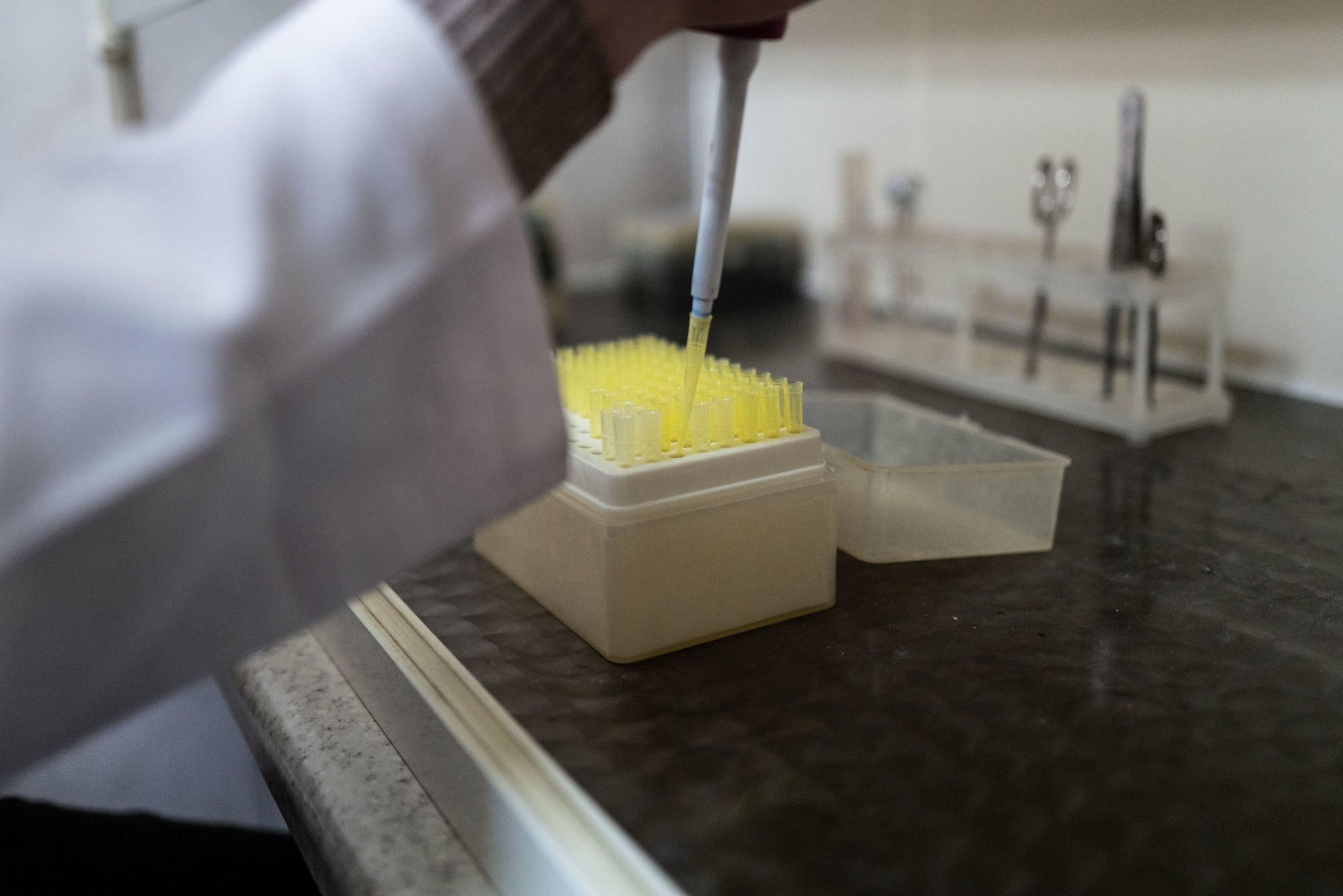

Hvoziuk’s decision to stay in Ukraine and continue her work was influenced, in part, by the potential of her research to help Ukrainians survive in a war zone: She’s developing a new method to preserve blood donations at very low temperatures, or cryogenically, so that they can be stored for longer and transported across greater distances without expensive refrigeration.

She hopes to help Ukraine “significantly increase the stocks of donated blood, which is so necessary today on the Ukrainian front.”

A few months after the war began, the broader scientific community sought ways to support Ukrainian scientists. On June 2, 2022, for example, the coalition of seven science academies from Europe and North America that issued the letter with the 10-point plan met in Warsaw, Poland, to coordinate how they could support Ukrainian science and innovation, both inside and outside of the country.

One relevant program called SEED — Scientists and Engineers in Exile or Displaced — has its origins in the American withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, when the U.S. National Academy of Sciences wanted to help evacuate and relocate a small group of at-risk Afghan scientists.

Soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences refocused and expanded the scope of SEED to help Ukrainian scientists. Now, the aim is to provide “a mechanism to help relocate these refugees and their families temporarily in neighboring countries and to connect them with research institutions so that they can continue to be part of the international science community,” according to the U.S. National Academy of Sciences President Marcia McNutt in a post on the Academy’s website.

In the beginning, the program was largely focused on providing assistance to researchers who had already been displaced and were residing in other countries, said Vaughan Turekian, a former science and technology adviser to the U.S. Secretary of State, who currently serves as executive director of the Policy and Global Affairs Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Turekian was heavily involved in the original SEED program, and is now an advocate for increasing its scope in Ukraine.

But now, the goal is shifting again, Turekian said, because if the Ukrainian scientific community is to survive and thrive in the long term, those who remain on the ground need the most support. “Our focus is really to help support the researchers who are still inside Ukraine,” he said. “And build up their connection with those outside.”

From a practical standpoint, ongoing attacks against Ukrainian cities have limited the options of governments and scientific bodies looking to assist Ukrainian scientists. “The focus in the near term has to be about building human capital and capacity because the infrastructure is going to be much, much harder in the near term until there is reduced concerns about ongoing bombings and attacks,” he said. “You don’t want to put in a mass spectrometry lab if you have no access to reliable energy or water.”

The war in Ukraine is far from over. From Kyiv to Kharkiv, Russian drones and cruise-missile strikes continue to hit civilian targets on a near-weekly basis. Air raid sirens scream through the night. In eastern Ukraine, fighting has devolved into a war of attrition; still, with no clear end in sight, for regular Ukrainians, life must go on.

In follow-up messages sent over Telegram from Kharkiv, Hvozdiuk told Undark that the war has upended her outlook on both her life and her work. “Our values have changed a lot, we began to value time, relatives, friends more, there was a great desire to help and work for the development of Ukraine,” she wrote.

For Ukrainian scientists and their institutions, the road to recovery will be long and difficult. “We will have a lot of work. To replace the scientists who do not return, it will be necessary to train a worthy replacement,” she wrote. “I really hope that our state will begin to pay more attention to our science and our developments, most of which are directly related to the war and could be used today.”

Despite the circumstances, Hvozkiuk told Undark that she will stay in Ukraine.

Note: Numerous interviews for this story were conducted with the help of Yulia Zubova, who aided with translation during conversations with Ukrainian speakers. She also provided logistical support and supplemental reporting.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

It’s not a problem. I’m a Ph.D. of Materials Science and now an officer of Ukrainian Army. I will return to my favorite researches just after Victory.

Ukraine will win

Everything will be 450!