Keeping the Lights On at Ukraine’s Research Nuclear Reactor

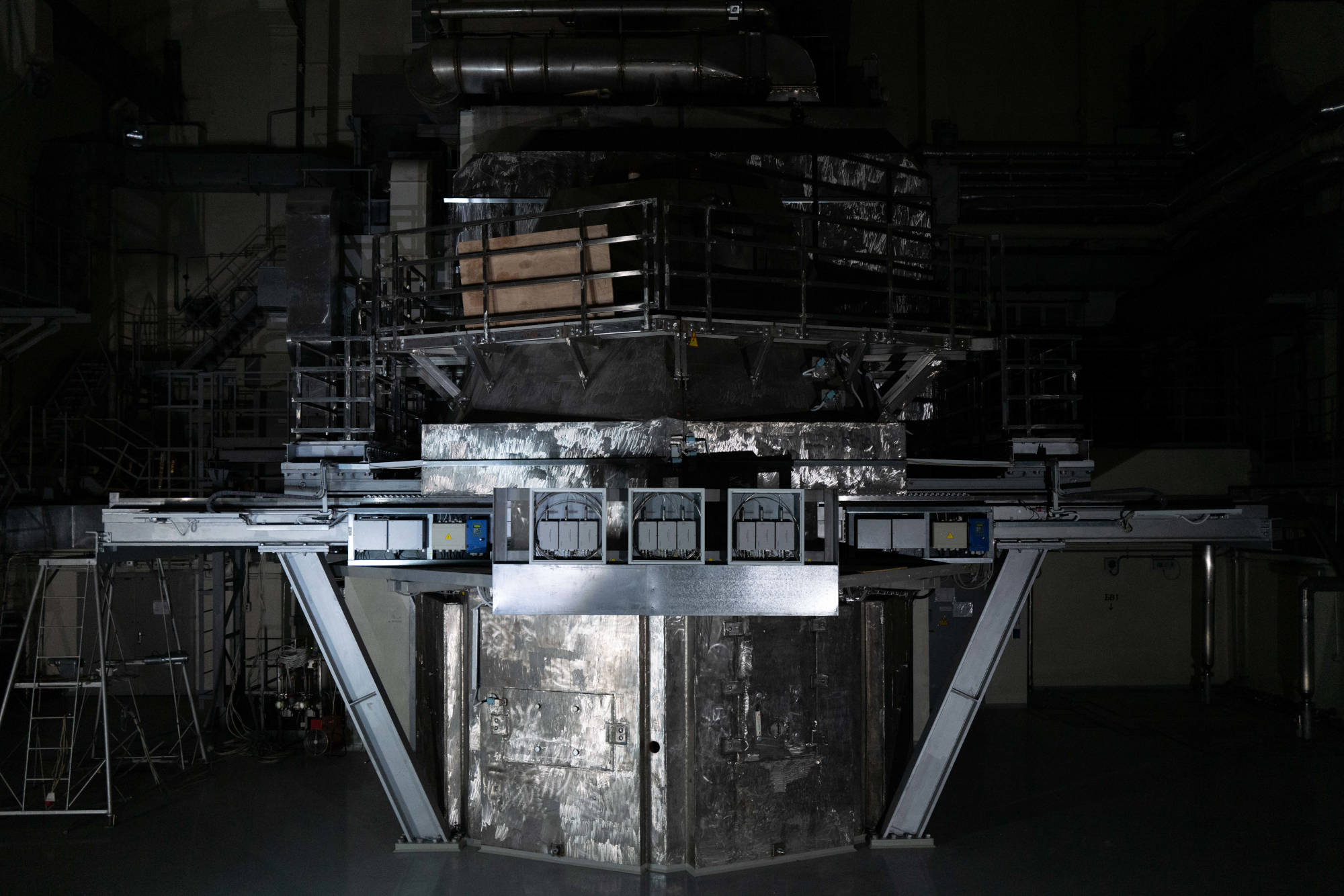

In the pre-dawn hours of March 6, 2022, a Russian rocket struck a large, white-and-gray-sided building in the eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv. Although the building could easily be mistaken for a warehouse from the outside, inside it contained a nuclear research reactor known as a neutron source. Neutron sources are often used for medical research — in this case to create an isotope commonly used to diagnose certain forms of cancer — and this one helps train Ukraine’s nuclear scientists and technicians.

The neutron source is located at the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, the former home of one of the Soviet Union’s first nuclear weapons development laboratories. The neutron source was funded and constructed under a 2010 deal between Ukraine and the United States in which the former agreed to remove Soviet-era nuclear fuel stockpiles in return for support for domestic nuclear power and research programs.

Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, around 2,000 people worked at the institute. Mykola Shulga, KIPT’s director, told Undark that more than 750 staff members have since fled, some to other parts of Ukraine, and some to Europe.

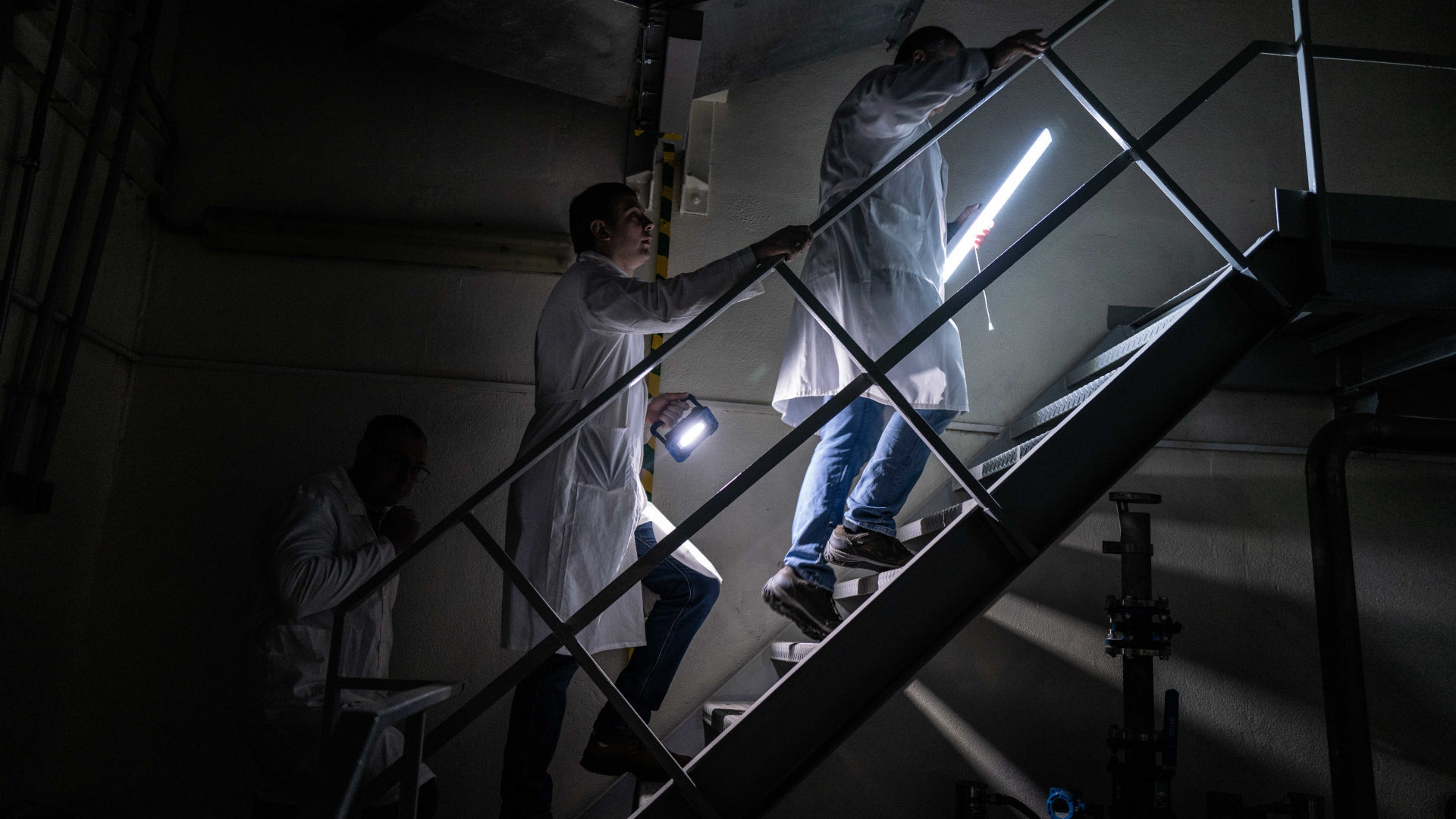

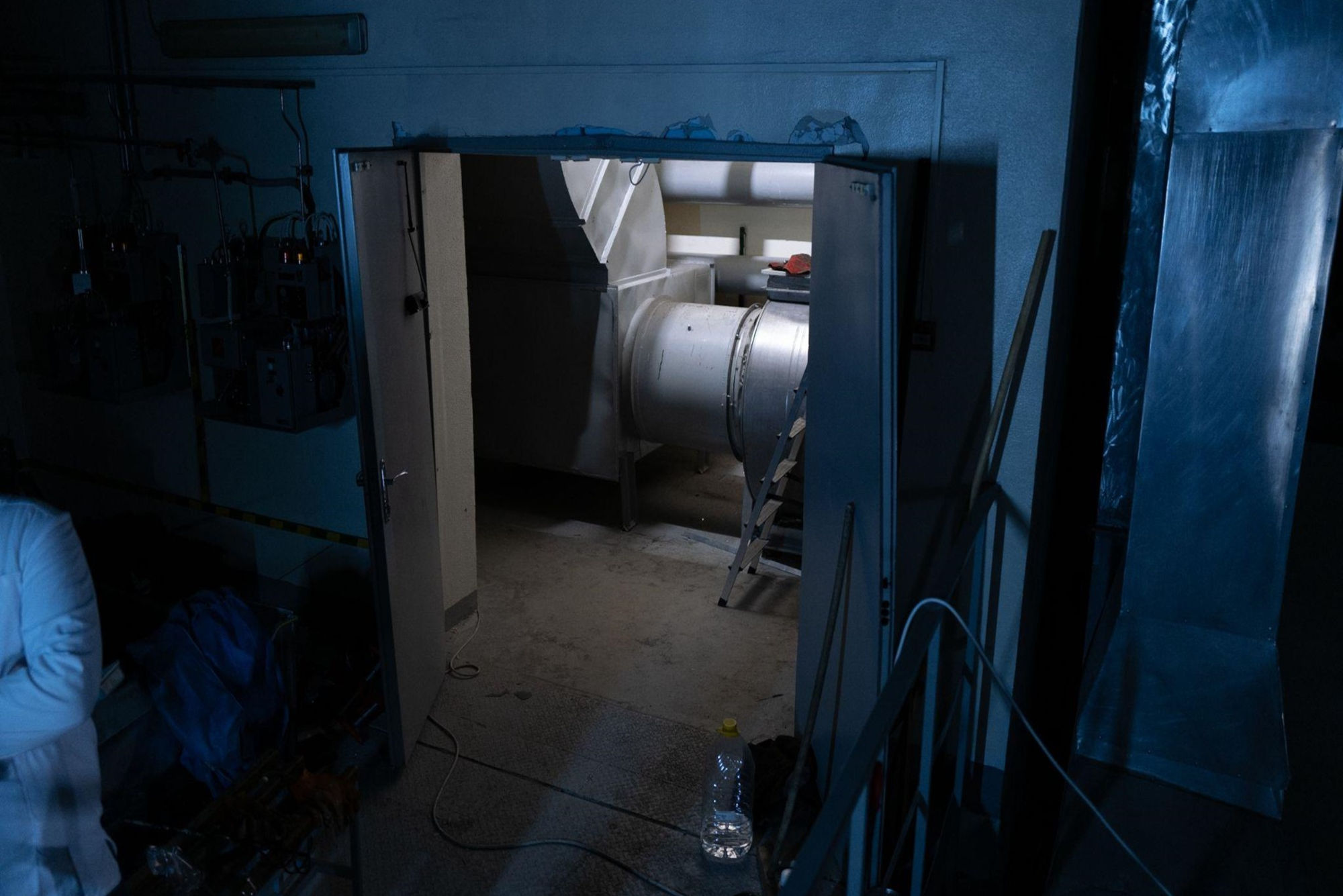

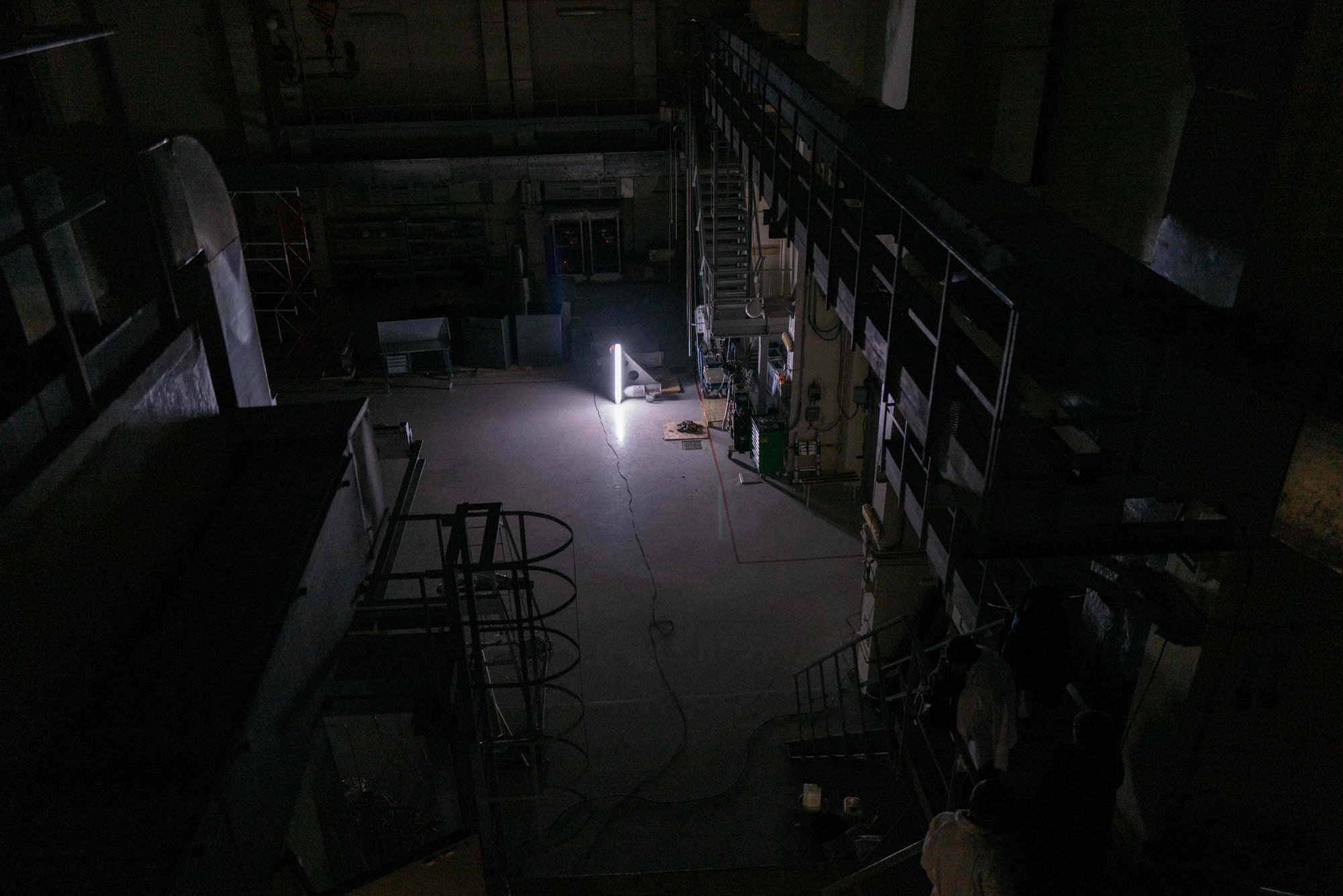

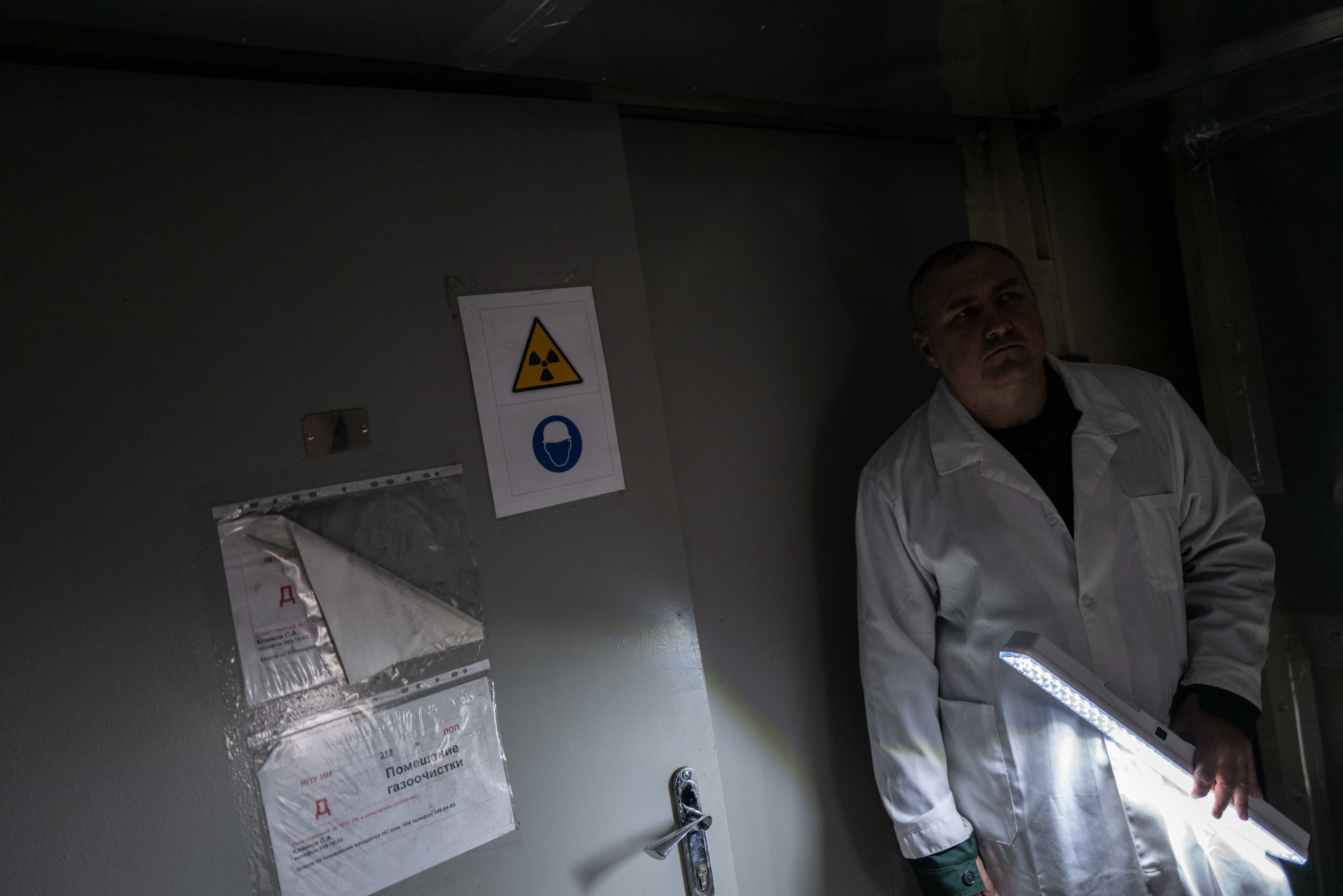

Although the reactor itself was not damaged in the 2022 attack, several key parts of the facility were, including a power transformer critical to its continued operation. When Undark was granted access to the facility in February 2023, technicians were also busy repairing an air filtration system that had been destroyed by the rocket’s shockwave.

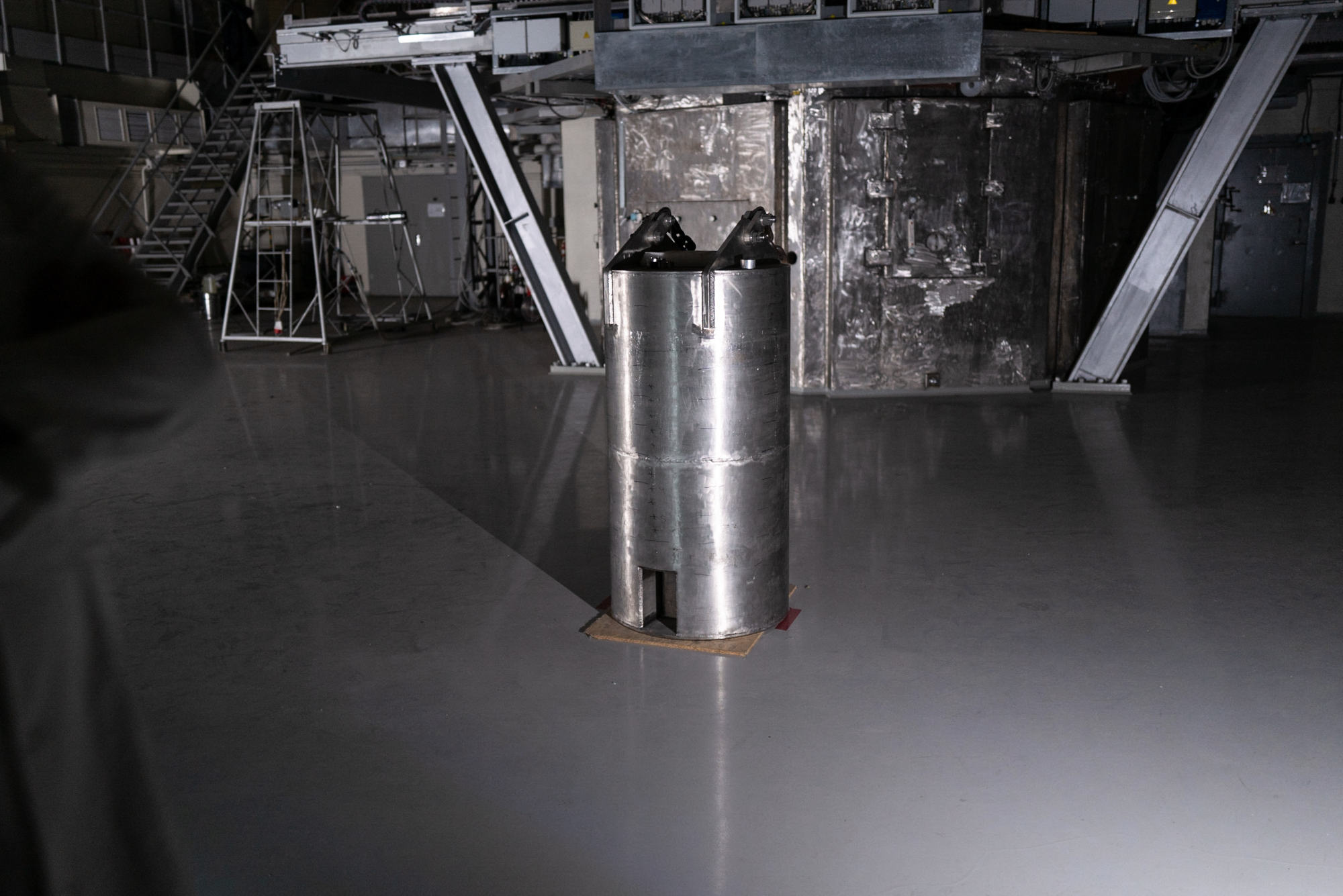

The neutron source uses a fraction of the nuclear fuel needed to power a standard nuclear reactor. But while most nuclear power plants use uranium containing between 3 and 5 percent of uranium-235, the isotope capable of sustaining a nuclear chain reaction, the neutron source’s fuel is enriched to 19.5 percent, putting it just under the threshold of being classified as highly enriched and close to weapons grade. Highly enriched uranium is considerably less stable, and therefore more dangerous from a nuclear security standpoint. Although the risk of an accident is low with such a small amount of fuel, a direct hit to the reactor or KIPT’s fuel storage could potentially release damaging amounts of radiation into the surrounding area, according to KIPT staff.

As the war in Ukraine continues into its second year, the challenges for scientists and staff at KIPT are not likely to abate soon. “Everything is now much more difficult than it was in normal life,” said Andrei Mytsykov, the neutron source’s head engineer, speaking through a translator. Despite their efforts, he added, staff at the facility don’t currently have the means to provide the levels of nuclear safety that international standards require.

Note: Numerous interviews for this story were conducted with the help of Yulia Zubova, who aided with translation during conversations with Ukrainian speakers. She also provided on-the-ground logistical support and supplemental reporting.