Does electromagnetic radiation from cell phones pose a public health risk? To some people, the question seems paranoid. To others, convinced that their devices are proven hazards, the question seems dangerously naïve. And therein lies a vexing challenge for science journalists: How do you cover an issue when the stakes for human health seem so high, scientific questions still linger, and passions run so deep?

THE TRACKER

The Science Press Under the Microscope.

At issue here is the low-energy radiation emitted by cell phones and other personal electronics. These kinds of electromagnetic fields don’t directly damage bonds in DNA, and the Federal Communications Commission, the Food and Drug Administration, and other government agencies generally consider them safe at the levels associated with cell phones. “The majority of studies published have failed to show an association between exposure to radiofrequency from a cell phone and health problems,” the FDA states unequivocally on its website.

It’s true, of course, that some individual studies have suggested potential links between this sort of radiation and a range of health problems. And in the next few weeks, the U.S. National Toxicology Program, part of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, is expected to release the final results of a $25 million study of the effects of cell phone radiofrequency radiation on rats. Preliminary results from the study, released in May of 2016, suggested a link between cell phone radiation and tumor formation.

At the same time, it’s possible to find data suggesting low-level risks from many things, ranging from fluoride to vaccines, even though there is little aggregate evidence of a public health crisis. And it’s worth noting that the NTP study also inspired skepticism from some scientists.

Still, as more people — and more and more children — spend time with cell phones, the murky margins of scientific evidence and lingering uncertainty are very likely to stir more concern and debate. And for reporters who step into this conversation and raise advocates’ ire, the backlash can be swift and robust. That response was on display last month, after the California Department of Public Health released new guidelines for “individuals and families who want to decrease their exposure to the radio frequency energy emitted from cell phones.”

In response, the magazine Popular Science ran a story under the headline “There’s no evidence that cell phones pose a public health risk, no matter what California says.” In the piece, Popular Science reporter Sara Chodosh gave a rundown of why it’s so difficult to study the safety of phones, concluding: “There’s no evidence that cell phones are dangerous to your health. Period.” She also accused the State of California of fear-mongering about phone safety, and ended her piece by telling readers, “Heck, you could duct-tape [your phone] to your face if you so choose.”

Shortly afterward, in a brief segment on the public radio show Science Friday, host Ira Flatow and his guest, Popular Science senior editor Sophie Bushwick, built on Chodosh’s story. “There’s no strong evidence to suggest that these devices aren’t safe,” said Flatow. “It’s creating a lot of fear around an issue that we’re not sure people actually need to be afraid of,” Bushwick explained on air.

Within days, activists began writing to Science Friday, accusing the show of spreading misinformation, endangering public health, and dramatically misrepresenting the science. The activists connected through email lists, and many of the irate messages seemed to follow a pre-written template. (One email writer in Maryland, for example, after receiving a query from Undark, admitted that she had not actually listened to the Science Friday show.)

But the email messages — dozens of which were copied to staff at Undark — also included personalized, furious commentary on Flatow and Bushwick’s conversation. “I will not mince words. Your radio program about cell phones and the [California Department of Public Health] document was appalling,” began a message from Ellie Marks, a longtime advocate for safety warnings on cell phones and the founder and director of the California Brain Tumor Association. When I called up Marks, who became interested in this issue after her husband was diagnosed with brain cancer in 2008, she took particular issue with the tone of the coverage. “There’s an extensive amount of science on this. And Popular Science and [Science Friday] ignored that — to the point of sarcasm,” Marks said. “Saying that it’s okay to duct tape your phone to your face? I mean, even if you look at the user manual, they all tell you that you should not put a phone to your body!”

During our conversation, Marks suggested — without offering evidence — that both national cancer statistics and the Popular Science article could have been influenced by industry pressure. “We feel that they use people — they have certain people that they use to get their message out,” she said.

The Environmental Health Trust, a Wyoming-based nonprofit, has criticized the Science Friday segment and called on Popular Science to retract its original piece, offering a point-by-point challenge to large sections of the article. “This is a classic example, if you get a naïve reporter who doesn’t know much about the issue, and you give them the information that comes straight from the industry propaganda,” said Devra Davis, an epidemiologist and the founder of EHT, in an interview with Undark.

Davis, who has written books about tobacco and cell phone safety, described the Popular Science article as “a remarkable piece of disinformation,” and expressed disappointment that Science Friday had picked it up. “That was really a tragedy, as far as I’m concerned, and really irresponsible on their part,” Davis said.

It’s certainly true that Davis and other advocates can point to numerous peer reviewed studies suggesting a possible link between non-ionizing radiation — of the kind emitted by cell phones and other personal electronics — and a host of health conditions, including miscarriage, glioma, neurological problems, and male infertility.

And it’s not necessarily the case, as the Popular Science article and other coverage sometimes suggests, that because these sorts of non-ionizing radiation cannot break the bonds in DNA, they cannot have an impact at the cellular level. “We know they interact with biological tissue. Period,” said Jerry Phillips, a biochemist at the University of Colorado-Colorado Springs who has published extensively on the effects of such radiation on cells. “We don’t know what the nature of that interaction is, number one. And number two is, we still don’t have an idea of what the active component is, or components are, because we don’t have a clue as to what constitutes a dose.”

For Davis, this kind of uncertainty is worrying. “We are currently in the middle of the largest experiment in human history, for which people have never given consent,” she said.

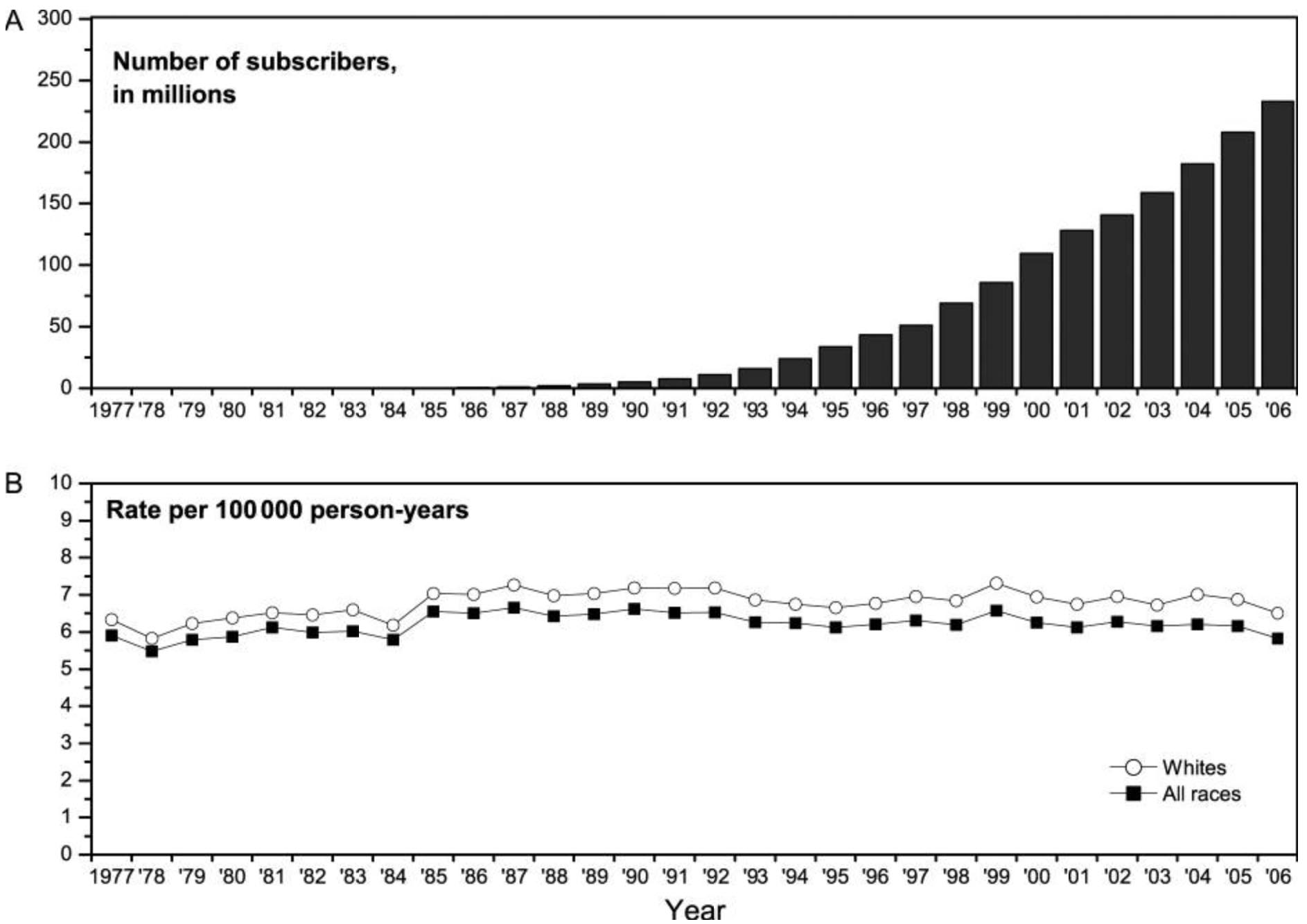

Not everyone is convinced, though, that these findings add up to anything remotely like a full-blown public health emergency. Much of the most-cited research in this field has been performed on rats or tissue cultures, not human beings. Large epidemiological studies can suggest correlations, but they struggle to establish clear lines of causation. And perhaps most tellingly, nearly two decades after the widespread introduction of cell phones in industrialized countries, brain cancer rates have not spiked.

“There’s nothing much happening with brain cancer. It’s just flat. The same rates per 100,000 people are getting brain cancer today as they were before cell phones,” said Simon Chapman, an emeritus professor at the University of Sydney School of Public Health and the lead author of a 2016 study of the relationship between cell phone adoption and brain cancer rates in Australia. “I’m not seeing any major international or national cancer bodies who can gather together the best evidence, the best experts, and publish consensus statements saying that this is something the public should be worried about,” Chapman told Undark.

“The only groups waving the red flag and saying ‘stop’ are fringe groups, people like Devra Davis and her group of cohorts,” he added. For her part, Davis simply counters that brain tumors take a long time to develop — and there is evidence that glioma rates are, in fact, beginning to rise.

Science Friday’s Flatow did not respond to multiple requests for comment, though in an email to one of his many agitated email correspondents, which was forwarded to Undark, the host indicated that upon release of the looming National Toxicology Program report, Science Friday plans to “revisit the issue in depth, as we have done in the past.” In a phone interview, Rachel Feltman, the science editor at Popular Science, stood by the magazine’s story. “All the reputable health agencies have looked at the available studies and the available evidence and concluded that cellphones almost certainly are not a health risk,” Feltman said.

“I think we make it very clear in our piece that, yes, there are individual studies that can be interpreted that way,” she added. “But when you look at the body of evidence as a whole, the scientific consensus is clear.”

In some ways, the disagreement here seems to hinge on how different stakeholders understand the word “evidence,” and how much of it they believe is necessary to present an actual risk. Does “evidence” simply mean that there is some reputable research out there that points, however tentatively, to a possible effect or impact — and if so, is that by itself something to fret over? Or does “evidence” mean, as Feltman suggests, that a clear scientific consensus has coalesced around one particular conclusion or another?

These aren’t, of course, strictly scientific questions. They’re moral and political — and even emotional and psychological ones, too. And all of that cuts to the heart of a quandary facing science journalists everywhere: On questions of scientific uncertainty and health, what does the public need to know? Should the press, in covering cell phone safety, give equal weight to every incremental study suggesting some possible health risk — or provide a platform for worried advocates each time such a study turns up in the scientific literature? Such a world would be a paralyzing and fearful place. And of course, some preliminary scientific concerns do prove overblown in the fullness of time.

At the same time, it’s sobering to think of a world where the public is simply assured that everything is definitely okay — at least until a consensus forms and enough scientists get together and tell them that it’s not. Science is littered with examples of toxins and pollutants that were long thought to be safe, or at least not demonstrably dangerous — tobacco, lead paint, or even the radium-laced products for which this very publication is named — only to be revealed later as hazardous.

So are studies that suggest a possible risk from the low-energy radiation emanating from cell phones and other tools of modern life something to worry about — particularly against the backdrop of far more numerous studies that, at least to date, have found no real cause for concern? Probably not — until they are. And it’s that sort of fuzziness — always just shy of absolute certainty — that makes reporting on the issue so dicey.

“If a single study shows a result of something, that’s not quite the same as saying there’s evidence that that thing is true,” PopSci’s Feltman said. “It means one study suggested that there might be evidence that that thing was true.”

That’s exactly right. But it’s also cold comfort for folks like Ellie Marks, who are unshakably convinced that technology makers — and the press — are ignoring too many of those single studies.

“No one is saying give up your cell phone,” Marks said. “We want people to make informed decisions for themselves and their families about something that even children are using.”

Michael Schulson is an American freelance writer covering science, religion, technology, and ethics. His work has been published by Pacific Standard magazine, Aeon, New York magazine, and The Washington Post, among other outlets, and he writes the Matters of Fact and Tracker columns for Undark.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

If Jerry Phillips cannot tell how non-ionising radiation affects biological tissue-how can he know it does? there must have to be some observable change .

The cell phone radiation is real. We are surrounded by phones. Everybody has 2 phones, 1 for work, 1 table, 1 wifi tv, we want wifi to improve our life but I’m afraid that will be dangerous for our health. You can find out more: https://emfshieldprotect.com/

This is far from over. Science is to find out the truth to the point that there are NO more questions to be asked and nothing (at the time of the subject being tested) can dispute the findings. But when new ways of testing are created, these subjects should be tested again to see if the findings change. Seeing that there are still questions and it has not been clearly defined to the point that no one can argue against it, the science is failing.

The real threat to public safety is the vocal minority of educated conspiracy theory believers and the many, many fake sites and fringe organizations that feed their paranoia. Just read the comments for this article. People are posting their excuses for ignoring evidence they don’t like (government is in the pocket of industry, universities are in n the pocket of industry, etc, etc). It’s a sad and, unfortunately for us, dangerous trend that is leading to actual policy. People who believe in chemtrails are pressuring officials to deny climate change or get permission to send their unvaccinated children to public schools.

One of the problems we have nowadays is that the FCC, the FDA and other government agencies have proven themselves to be little more than paid whores for the industries they’re supposed to be regulating. So whatever they say on a particular subject is suspect. (This opinion is from a left-leaning electronics engineer.)

The mobile phone cause addiction for sure, now I use it only when no other options, with shielding between the phone and me to eliminate direct EMF radiation and with air-tubes (http://emfclothing.com/en/accessories/347-radiation-free-air-tube-headset-airobic-sport.html)

ALL the main regulatory bodies without exception have fulsome pious-sounding phrases about following the preacuationary principle – not even mentioned in the article above-.

At he same time the above waffle about “consenseus” is complete nonsense. That is politics and buraucracy not science. In science (if it still exists anywhere on the planet) ONE STUDY showing harmful effects from microwaves scotches for all time the thesis the industry and governments rely on, that said radiation is harmless., There is not ONE such paper, there are not even hundreds, there are many thousands. Of just one paper one can say : “Right, now we know the thesis of non-harm has been scotched for all time – unless the paper was poorly designed or badly carried out or incorrectly recorded and analysed. That those negative condition should hold for thousands of papers going back many decades from many countries, from every continent on the planet but Antarctica, covering many different body systems and levels of inquiry – viz epidemiological, histological, disease , neurological, chemically-based, electrically-base etc etc etc – is completely an utterly impossible.

Why is it scarcely anyone can or will think straight?

As a medical anthropologist, I suggest that journalists interested in such issues also look past national boundaries and drink from the fountain of less industry-controlled scientists in Europe and elsewhere.

But that would defeat their purpose. If they did, what they would find is that there actually 1 large stidy do e by the industry in Europe, albeit on “handsets”, which actually expose users to higher levels of unmodulated EMF. That study found that there was no link with their use and brain tumors. The way they reached that conclusion? By designating the largest and group of users as “controls”. The other two larger studies done around the same time? They left the datasets “speak for themselves” and pointed out unequivocal link that scaled up with user hours.

Ellie, Theodora, Devra and others commenting on this issue may be struggling to understand the real meaning of the NTP rodent studies with respect to their conclusions on the levels of evidence found. The adjective most used to describe the findings is EQUIVOCAL. This word is not commonly used in daily conversations so it might be useful to know some of the synonyms which are more common. The top ten in my thesaurus are: doubtful, uncertain, ambiguous, ambivalent, dubious, evasive, muddled, puzzling, unclear and vague.

So, in this 10-year, 25 million dollar study – exposing rats to intensities of RF between 1,875% and 7,500% higher than FCC maximum permissible exposure for humans, which found than the level of evidence of adverse health effects was EQUIVOCAL – know that it means that it is UNCERTAIN, DUBIOUS, MUDDLED, UNCLEAR or VAGUE. Or, in other words – the jury is in – the exposures are safe – and it’s time to put away the fear-mongering and conspiracy theories and get on with your life.

Your article is an important step in a very necessary direction involving not only cancer induced (or not) by electromagnetic radiation but all scientific and medical issues about which our understanding proceeds more slowly than many people would like. That includes many issues (hot-button matters for many people) including but not at all limited to radiation-preserved fresh food, vaccines, GMO’s, and tick-borne infections about which less is known than would optimally be available.

The direction I’m referring to is an explicit acknowledgement that different people have different threat responses to uncertainty, so that what is anxiety-provoking for some is not anxiety-provoking for others. This is very much complicated by the fact (and it is a fact) that our scientific knowledge necessarily advances far more slowly than is comfortable for many anxiety-prone individuals. At the same time the evaporation of authority (another complicating factor) leads some responsible people to overstate the conclusory value of present-day knowledge out of fear for what they see as the endangerment of inarguable social values (herd immunity and prevention of harm, among others).

The science journalism community would do well to continuously acknowledge the fact that people have different comfort levels regarding scientific reassurances and that while some will be happy with announcements that no problems have been encountered “so far,” others will prefer to avoid still-questionable situations until greater certainty is available. In other words some (like myself) are willing to be guinea-pigs and some are not. There is no reason at all for scientists and those who speak for them not to acknowledge, accept and work with these differing levels of sensitivity.

Authoritarianism (regardless of our most recent election) is on the way out. This seems to be a continuing problem for many in our medical and scientific communities. Time to move on, people. Time to accept everyone as individuals with full agency and the right to make their own decisions regardless of your (our) opinion.

…CONTACT: Virginia Guidry, 919-541-5143,

HIGH EXPOSURE TO RADIOFREQUENCY RADIATION LINKED TO TUMOR ACTIVITY IN MALE RATS

High exposure to radiofrequency radiation (RFR) in rodents resulted in tumors in tissues surrounding nerves in the hearts of male rats, but not female rats or any mice, according to draft studies from the National Toxicology Program (NTP). The exposure levels used in the studies were equal to and higher than the highest level permitted for local tissue exposure in cell phone emissions today. Cell phones typically emit lower levels of RFR than the maximum level allowed. NTP’s draft conclusions were released today as two technical reports, one for rat studies and one for mouse studies. NTP will hold an external expert review of its complete findings from these rodent studies March 26-28. From NIH Report

Brain cancer incidence rates have continued to be flat for almost an additional decade past the chart shown in your article. See the latest chart from the National Cancer Institute which goes up to 2014. Rates have slightly decreased: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/brain.html

Hey Lorne,

I assume your business making wireless components is still going strong. Try reading the rest of the facts you omitted here as you have misstated the facts

PUBLIC RELEASE: 24-FEB-2016

Malignant brain tumors most common cause of cancer deaths in adolescents and young adults

American Brain Tumor Association funds first comprehensive study of 15-39 year-old population

AMERICAN BRAIN TUMOR ASSOCIATION

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2016-02/abta-mbt022216.php

Chicago, Ill., Feb. 24, 2016 – A new report published in the journal Neuro-Oncology and funded by the American Brain Tumor Association (ABTA) finds that malignant brain tumors are the most common cause of cancer-related deaths in adolescents and young adults aged 15-39 and the most common cancer occurring among 15-19 year olds.

The 50-page report, which utilized data from the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS) from 2008-2012, is the first in-depth statistical analysis of brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumors in adolescents and young adults (AYA). Statistics are provided on tumor type, tumor location and age group (15-19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34 and 35-39) for both malignant and non-malignant brain and CNS tumors.

https://forcedfluoridationfreedomfighters.com/a-preliminary-investigation-into-fluoride-accumulation-in-bone/

Anyone who thinks that delivering any medication by dumping it into public water supplies is scientific is scientifically illiterate. As for fluoride, it is highly toxic and a cumulative poison, like lead, arsenic, and mercury. I have asked many forced-fluoridation fanatics to tell me how much accumulated fluoride in the body they think is safe. So far not a single one of them has been able to answer the question. It is unlikely to just be a coincidence that the US, Australia, and Ireland, which have had high rates of forced-fluoridation for decades, also have high rates of joint problems, and poor health outcomes in general.

I spent an hour on the phone with Michael. He certainly cherry picked to put his slant on this piece. If this is truth, beauty and science I am a cow.

This is just more industry propaganda. There is an abundance of excellent peer reviewed published science showing the correlation between wireless radiation and brain tumors, thyroid cancer, salivary gland tumors, damage to fetuses, infertility, testicular cancer and more. I am neither a fear monger or a conspiracy theorist. I know the science, I know the collusion between the FCC, CTIA, and our federal legislators. And I know the victims. Rachel Feltman is incorrect. The last sentence is so true – Americans deserve to know the truth so they can use this as safely as possible. And that is what the California Department of Health has done. No one is saying stop using cell phones- but unless you are an idiot, please don’t duct tape it to your face.

How is Rachael Feltman to make this statement about “scientific consensus” quoted in the article above “yes, there are individual studies that can be interpreted that way,” she added. “But when you look at the body of evidence as a whole, the scientific consensus is clear.”

This is not true. In 2011, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer classified this radiation (RF) as a ‘possible carcinogen’ largely due to published scientific evidence of increased brain cancer in long-term heavy users of cell phones. “Heavy use” was defined as about 30 minutes per day.

Dr. Samet, Senior Scientist, Chair of the World Health Organization’s International Agency for the Research on Cancer 2011 EMF Group stated that “The IARC 2B classification implies an assurance of safety that cannot be offered—a particular concern, given the prospect that most of the world’s population will have lifelong exposure to radiofrequency electromagnetic fields” (Samet 2014). Even Emilie van Deventer, of the World Health Organization’s EMF Project, was quoted in The Daily Princetonian stating, “The data is gray. It’s not black and white…. There is no consensus, it’s true.”

Please see the Environmental Health Trust response and links to the scientific sources here https://ehtrust.org/retract-popular-science-article-cell-phones-arent-public-health-risk-no-matter-california-says/