Paris has long been the dream of many a tourist. In the 17th century, it would have been a nightmare.

WHAT I LEFT OUT is a recurring feature in which book authors are invited to share anecdotes and narratives that, for whatever reason, did not make it into their final manuscript. In this installment, Holly Tucker shares a story left out of her new book “City of Light, City of Poison: Murder, Magic, and the First Police Chief of Paris.”

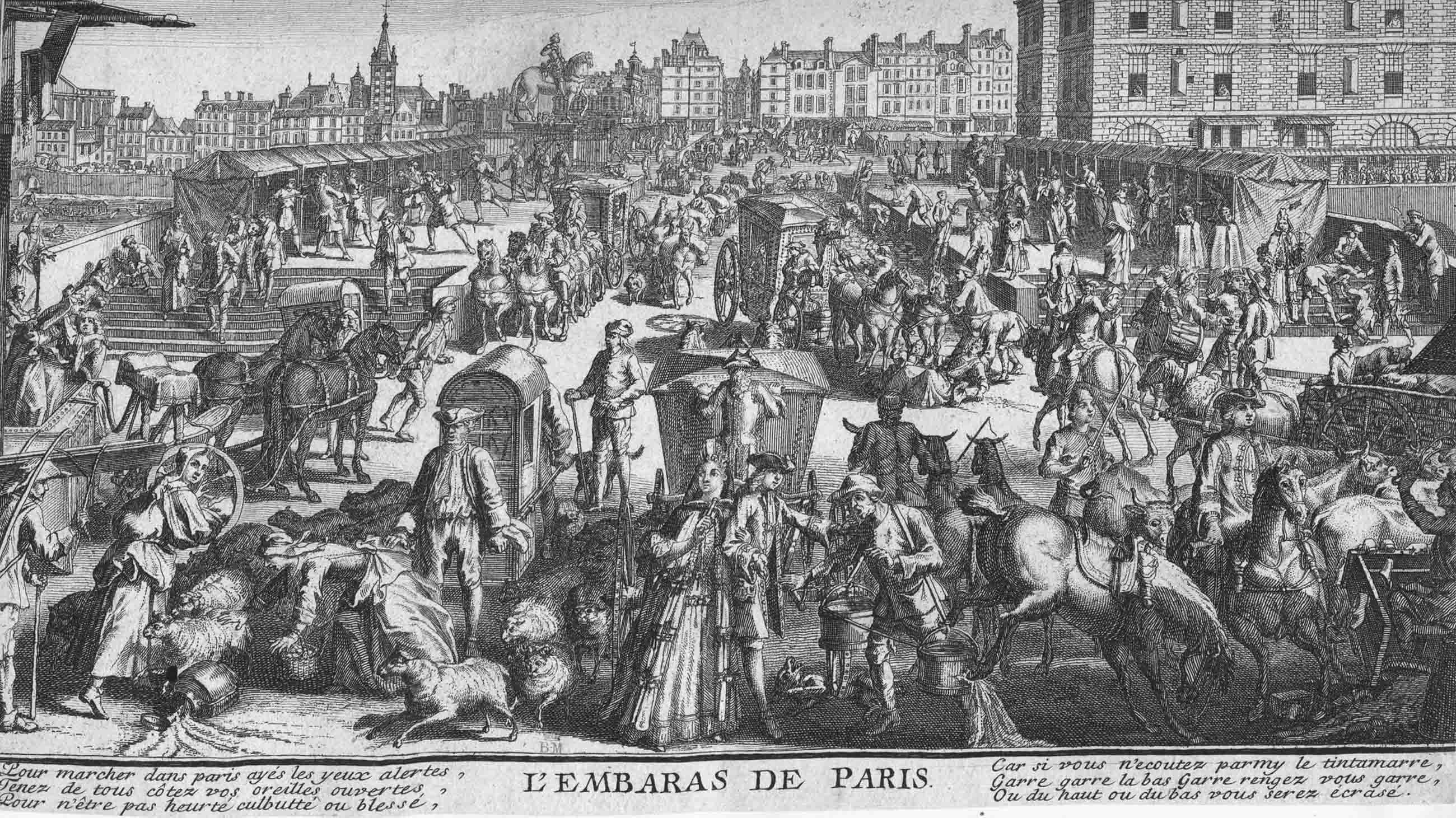

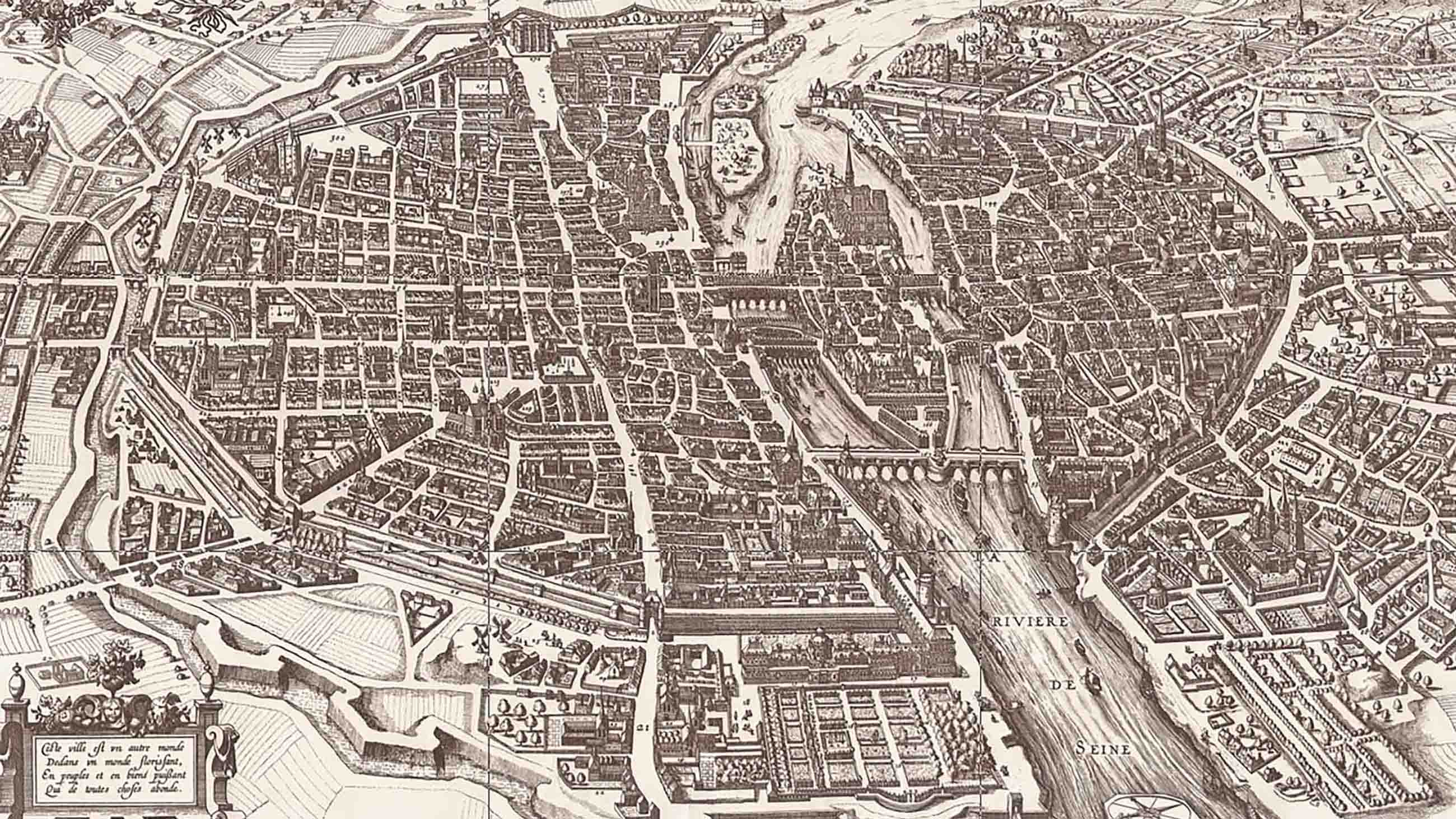

Slosh from chamber pots thrown from windows mixed with dirt in the city’s unpaved streets to form a sulfurous-smelling stew. On Thursdays and Fridays, Parisians had no choice but to walk through inches of thickened blood that slaughterhouses tossed into streets with names like Cow Foot (Rue du Pied-de-Boeuf) and Tripe (Rue de la Triperie), turning the mud in those neighborhoods permanently red.

The filth of Paris was inescapable. It attached itself ruthlessly to clothes, the sides of buildings, and the insides of nostrils. “Paris is always dirty,” a British visitor observed. “By perpetual motion dirt is beaten into such a thick black unctuous oil, that where it sticks, no art can wash it off. … Besides the stain this dirt leaves, it gives also so strong a scent, that it may be smelt many miles off.”

Although King Louis XIV had set his sights on building Versailles, his finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert pushed for new efforts to clean up the country’s capital. It was time, Colbert argued, to “purge the city of what was causing its disorders.”

In the fall of 1666, a group of 16 men streamed into the palatial home of Pierre Séguier, the royal chancellor, on the Rue de Grenelle for the first meeting of the committee. They gathered in the immense second-floor gallery, which boasted some of the most elaborate architectural detailing in Europe. One side of the meeting hall was lined with soaring windows topped with colorful midcentury frescoes in elegant plaster frames called gypseries. A long table covered with rich purple felt dominated the center of the room. Colbert sat at the head of the table, Séguier at the other end. Colbert’s uncle, the irascible Henri Pussort, was at the finance minister’s side. Thirteen other committee members, handpicked by Colbert and Séguier, filled the remaining seats at the table.

The men quickly settled on the major areas of concern: gun violence, access to drinking water, price gouging on essential provisions (bread, meat, and of course, wine), brothels and prostitution, and prison conditions. But one problem took precedence over all else: the city’s notorious, stinking mud.

For centuries, royal edicts attempted to cajole residents to take better care of shared public thoroughfares. In 1563, Charles IX had ordered that “with no exception,” every property owner must tidy up in front of his own residence at precisely six o’clock every morning and again at three in the afternoon. Homeowners were to amass all “mud, trash, and other filth” against the wall of the building or in a basket until the trash collector arrived. The edict also forbade inhabitants to throw any household or human waste out the window and into the street. This, too, should be neatly swept toward the walls or kept in a basket. Citizens were alerted to the edicts by postings in public squares and announcements throughout the city by town criers. Violators would be fined.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s minister of finance. (Visual: Philippe de Champaigne, 1655; Metropolitan Museum of Art/Wikimedia Commons.)

But as the continuing filth of the streets revealed, fines were no deterrent. A 1608 edict was even more specific: Instead of simply pushing the dirt toward the walls of buildings, inhabitants were ordered to work together as a brigade, twice a day, to push detritus from the front of their homes toward the river. After each dumping of “urine, cooking grease, and bathwater,” they were to rinse the street with at least two buckets of clear water. And just as butchers were forbidden to leave animal excrement in public passageways, residents were forbidden to leave their own human waste in the streets. In 1637, 1638, 1650, and 1660, still more edicts were issued. All reiterated the same ineffective regulations. Paris streets still oozed vile muck.

Colbert began the meeting by presenting a Monsieur Galliot, an enterprising commissioner in the Marais quarter who had offered to take over the responsibility for street cleaning. It would be an immense task. Galliot said he would need to coordinate with each of the city’s 47 other commissioners to organize teams of men to shovel the worst of the filth out of the narrow streets in their quarters. Horses and carts would then be needed to transport the mud either to the Seine, where it could be dumped, or to the main gates of Paris, where it could be left outside the city walls. If the fall rains began before the cleanup was done (as they no doubt would), Galliot would have to begin the process anew.

Once the worst of the mud had been removed, Galliot explained, the commissioners would find it much easier to fine homeowners and shopkeepers if they refused to keep the spaces in front of their properties clean. In theory, the cleanup would be financed by the fines that each commissioner collected from residents who violated the mud laws. (Of course, this assumed that the commissioners were actually collecting fines and putting the money to its intended use, rather than pocketing for themselves.)

Galliot’s promises were huge, but his price was fair. At the urging of the Colbert committee, the commissioners unanimously agreed to turn the responsibility over to him.

Three weeks later, there was little evidence of progress. Not wanting to suffer the king’s wrath, committee members quickly lost patience. Speculation swirled among them that the city commissioners were putting obstacles in Galliot’s way because they were outraged that he was receiving preferential treatment and handsome payment for his efforts. To this, Colbert replied dryly that if the commissioners expected payment, they should do a better job of collecting the mud fines from inhabitants who refused to abide by the wishes of the king.

The Saint-Germain quarter, which sat directly across the river from the king’s palace at the Louvre, was the dirtiest of all. The committee interviewed representatives from the neighborhood to understand better where the problem lay. The quarter’s treasurer objected that street cleaning should not be the responsibility of individual neighborhoods; if this was something the king wanted, then it was something for which the king would have to pay.

Groans of frustration and cries of anger sounded through the room. The treasurer was ordered to assemble the area commissioner and a large group of “notable bourgeois” to rethink their stance.

On Nov. 10, 1666, the committee met once again, this time with all 48 commissioners in attendance, perched in low chairs around the periphery of the council table. The tension was palpable. Many attendees avoided eye contact with one another by admiring Séguier’s porcelain collection or the large ebony cabinet that held the busts of ancient emperors. If it did not occur to the commissioners looking at these decapitated heads of great men that their own heads would next be on the block, it should have.

Opening the meeting, Séguier surveyed the assembled commissioners. Eyes narrowed, he told them the king would soon tour the streets of his city, on foot, to inspect their work. Colbert’s uncle, the unyielding Pussort, reminded the commissioners that Galliot’s proposal was consistent with the king’s wishes. And Colbert produced a list of commissioners who were now formally assigned to assist Galliot: They were to return to Séguier’s home the next day to receive official instructions from Galliot, in the presence of Colbert himself.

The commissioners got the message. Paris’s streets began to clear. While the king never made good on his threat to tour them on foot, a contemporary observer was able to report just a few weeks after Colbert’s intervention that the streets “had never been so beautiful.”

But it did not last. A “cabal” against Galliot broke out among the commissioners, and soon the streets were as impassable as ever — in fact, in some quarters, they were even worse. Dirt, dung, food, and filth sat stinking at ankle-deep levels. The commissioners had gone on strike.

In December 1666, a group of angry commissioners demanded an audience with Colbert’s committee. But as they waited outside, Colbert dug in his heels. “The public will be served,” he spat, and anyone who did not obey would be swiftly dismissed. Séguier signaled reluctantly for the doors to be opened and the commissioners filed in. Shoulders squared defensively under their finely tailored tunics, they remained standing along the periphery of the committee table. “Please begin by explaining why you have requested this meeting,” the chancellor asked calmly.

Commissioner Le Cerf stepped forward and read aloud a formal complaint against not only Galliot, but also the committee itself for overstepping its bounds in matters of city oversight. It was signed by 36 of the 48 commissioners.

When Le Cerf finished, Colbert delivered his icy response. “This committee will not suffer the commissioners assembling to take resolutions that are contrary to those that have been made in this council.” On his signal, a guard briskly opened the door to the gallery and escorted them out.

Colbert had already decided what would happen next. Galliot, whom Colbert praised for his hard work and dedication despite the difficult challenges he faced, would continue his efforts. As for the others, he ordered that the most senior members of the cabal — the four most responsible for inciting the “sedition” — be promptly arrested. It was not practical to strip the other 32 commissioners of their duties if there was to be any hope of clearing the streets, but the message had been sent loud and clear: There would be no mercy for dissenters. A week later, Pussort reported with “much pleasure” that the remaining commissioners were requesting the king’s “humble forgiveness” for their behavior.

The committee continued its work in relative peace and quiet over the months that followed. The commissioners’ revolt, however, had provided important insights into the bureaucratic obstacles to imposing some sort of order on an unruly city. Paris could no longer be entrusted to the commissioners, especially if the committee wanted to make progress on the many other troubles that plagued the city.

Nicolas de la Reynie, Paris’s first police chief. (Visual: chapitre.com/ Wikimedia Commons.)

On March 15, 1667, on the urging of Colbert’s committee, the king created the position of Lieutenant General of Police. This person would possess far-reaching powers. He was to oversee “city safety, gun control as proscribed by royal ordinances, street cleaning, flood, and fire control.”

On Colbert’s watch, the police chief would have oversight of the city’s major markets as well as control of any unsanctioned gatherings in Paris. He would also have full oversight of the prisons at the Châtelet complex. The edict left no potential for further controversy with the commissioners. The “commissioners … will be subject to the orders and mandates of the Civil Lieutenant of the police.”

The challenge lay in finding someone who was not so ingrained in the system, someone with the creativity and determination to rethink a system that was clearly not working. As Colbert scanned the list, one man’s name rose to the top. Nicolas de la Reynie had earned a reputation as a hard-hitting lawyer from Bordeaux, with little patience for sloppiness. He had stood firm in his support for the king during a perilous uprising of the nobility two decades earlier. Louis XIV swiftly approved Colbert’s recommendation, declaring that he could think of “no better man or a more hardworking magistrate” for the job.

La Reynie dove full force into cleaning up the city. He imposed a “mud tax” on every Parisian who had a home or a business in the city. The tax was intended to offset the substantial costs related to street maintenance. There were swift and steep penalties for late payment or refusal to pay, including the immediate confiscation of the inhabitant’s furniture.

The police chief also required inhabitants to pitch in personally. At seven o’clock each morning, hundreds of men soon moved through the city ringing bells to announce it was time for street cleaning. Parisians young and old, some still rubbing the sleep from their eyes, stumbled out of their houses, brooms in hand, to sweep the filth in front of their homes into the middle of the street. Thousands of trash collectors followed behind them to haul the refuse outside the city walls.

To aid street-cleaning efforts, new ordinances forbade residents to tie animals outside their homes or leave the carcasses of dead beasts in public pathways. A first offense earned a fine; a second resulted in a beating.

La Reynie soon learned with frustration that what residents could no longer throw into the streets they kept in their houses. A commissioner surveying the neighborhoods north of the Louvre described the “infection and stink” permeating the insides of homes that were full of “fecal material and dead animals, a putrefaction that was as large in their homes as it was in the countryside.”

Still, La Reynie claimed victory over filth three months after his appointment, claiming that “horses are slipping around on the pavement because the streets are so clean now.”

An exaggeration, perhaps. But perhaps forgivable, considering that the world’s first modern police chief owed his rise, at least indirectly, to the once intractable buildup of filth in the streets. Now, if only his successors could get a handle on the enduring problem of dog waste — which unwary tourists are still having to scrape from their shoes more than three centuries later.

Holly Tucker is a professor of French and Italian and is in the Center for Biomedical Ethics and Society at Vanderbilt University. Her previous book was “Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution.”