How are you? Seriously, how are you feeling? Chances are you could be better. You are probably not actually sick — no need to deploy the fearsome weaponry of modern medical care — but a few details of your physical being could be improved. Perhaps you sleep poorly, or your back aches and your energy is down, or your neck is stiff, your skin is dull, and your bowels are a little weird.

BOOK REVIEW — “The Kelloggs: The Battling Brothers of Battle Creek,” by Howard Markel (Pantheon, 544 pages).

Complaints like yours have long fueled the careers of those who yearn to help. Your discomforts may be small in the scheme of things, but they still matter enough that you would doubtless pay well for all improvements, both in dividends of gratitude and in cold cash. And where there is adulation or money to be had, history’s entrepreneurs come flocking.

In our time, we have Dr. Oz, Gwyneth Paltrow, and all the various purveyors of diets, vitamins, elastic garments, and exercise equipment. Back more than a century ago, the fatigued and constipated could turn to the brothers Kellogg, a wildly effective wellness team whose intertwined paths from rags to riches and back around again animate Dr. Howard Markel’s latest foray into medical history.

John and Will Kellogg were born in Michigan in the ten years leading up to the Civil War to devout Seventh-Day Adventists living in anticipation of the imminent end of the world. Early on, the brothers saw the disappointments and impermanence of the flesh for themselves: Six of 16 Kellogg siblings and halfsiblings died in childhood, and both boys, though destined to live into their 90s, were plagued by chronic medical problems. John had recurrent tuberculosis, colitis, and an anal fissure that made the consistency of his bowel movements a lifelong obsession. Will, eight years younger, had severe malaria as a child and lost most of his teeth by age 20.

Personal experience with debility and discomfort led to an equal familiarity with the healing arts of the time, mostly a collection of blunt tools wielded by uninspiring, poorly trained practitioners. The orthodox medicine of the time was so relentlessly scary and ineffective that almost any alternative looked appealing by comparison. For young John Kellogg, the clear choice was hydropathy, a doctrine embraced by his mother based on the gentle healing powers of water in both bath and beverage form. At age 20, John matriculated at Dr. Russell Trall’s Hygeio Therapeutic College in Florence, New Jersey, to learn what he could and bring relief to others.

By the last decade of the century, he had succeeded beyond all expectations, as the chief of the Battle Creek “Sanitarium” (a word he himself coined). His “San” offered thousands of patrons per year luxurious accommodations with central heating, a whole-grain-based vegetarian diet, more than 50 kinds of baths, fresh air, sunshine, physical activity, “electrotherapeutic treatments,” and even orthodox medical care — for after Dr. Kellogg graduated from Trall’s water college, he earned regular medical credentials and became an accomplished surgeon. He ministered to guests personally, lectured all over the world, and wrote tirelessly on the health perils of meat, tobacco, coffee, tea, alcohol, tight clothing, and all forms of sexual activity. In his spare time, he tinkered with health food recipes in the San’s kitchen.

Meanwhile, trotting behind John, taking notes and ever at his command, his little brother Will was the San’s details guy, the business-trained factotum who made the place operate.

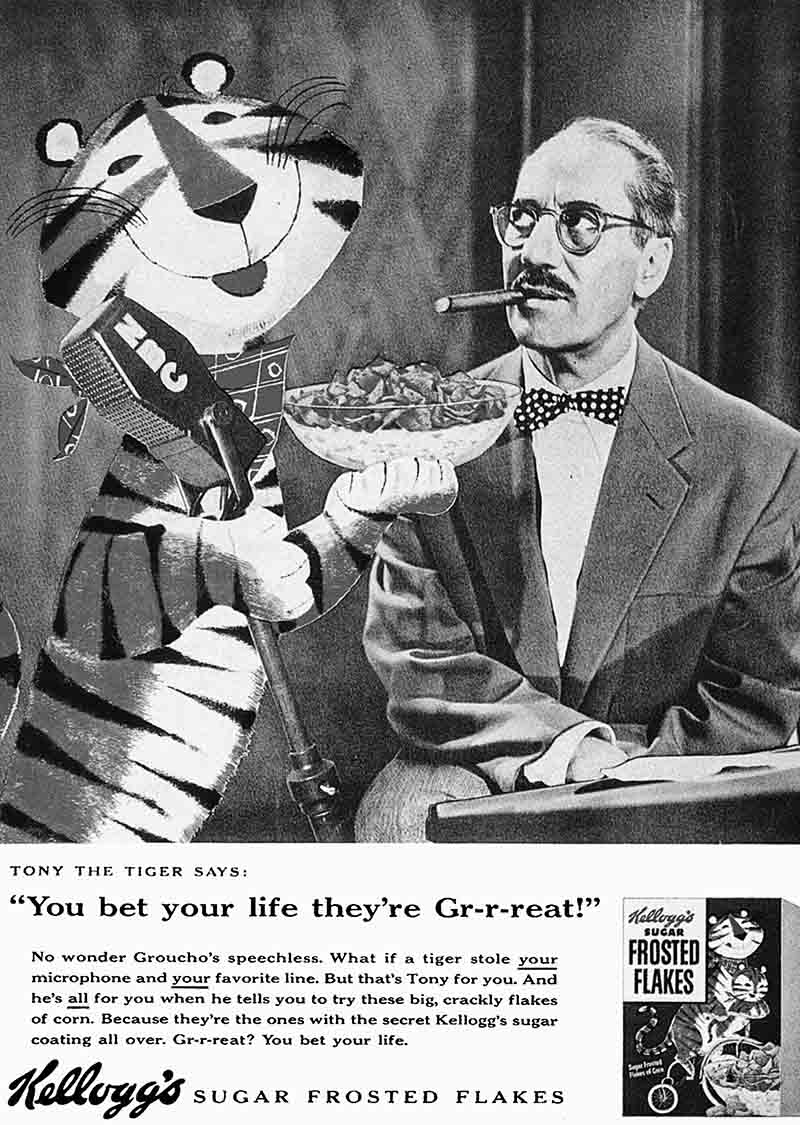

John was short, supremely self-confident, optimistic, charismatic, a natural leader. Will was quiet, insecure, emotionally stunted, and increasingly bitter at his secondary role in the operation. Just as Will’s resentment peaked, though, the two Kelloggs conceived and perfected several tasty forms of flaked cereal. Even now, it’s not entirely clear to whom the primary credit belongs, and the rights to the Kellogg’s Corn Flake drove an emotional and legal rift right through their partnership.

Ultimately it took the Michigan Supreme Court to grant Will primary use of the Kellogg brand name, as well as full control over the immensely successful cereal enterprise those first flakes spawned. Still, the brothers continued to spar about flakes, puffs, and fiber-rich granules in and out of court for the rest of their lives.

After 1902 they never worked together again, and neither brother managed nearly as well alone as they had as a team. Dr. John continued to attract the rich and famous to the San, but couldn’t keep the business in shape and eventually lost it to a group of investors. He aged into a garrulous, somewhat foolish figure who dabbled in racist eugenic theories, exercised plumply in a skimpy loincloth, and occasionally offered up a superbly textured bowel movement for public inspection.

Wealthy brother Will remained depressed, bitter, and isolated to the end of his days. He left posterity the ironic pair of legacies bearing his name: the shelves of highly processed, sugar-laden cereals routinely deplored by all health-conscious eaters; and the well-endowed W.K. Kellogg Foundation, whose grantees accomplish truly good works for children’s health.

Markel, a Michigan-born physician and professor at the University of Michigan, has never been the world’s smoothest writer. He struggles mightily to organize the details of his wonderful story, finally choosing a peculiarly circuitous path that spirals back and forth between brothers, issues, and events. The carsick reader will pine periodically for the style and humor of, say, T. Coraghessan Boyle, who novelized some details into a far smoother narrative in “The Road To Wellville,” published in 1993.

Even so, it’s worth sticking with Markel for the unvarnished confusions and contradictions of this prototypical wellness empire and the lessons it offers to the unwell of any era. Medicine and money, quackery and healing, philanthropy and Froot Loops — all are far more entangled than we like to believe.

Abigail Zuger is a physician in New York City and a longtime contributor to the science section of The New York Times.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Those are two fascinating brothers. Readers interested in how the story of Froot Loops and Cornflakes fits into the threads of vegetarian history might enjoy this episode of my radio history of vegetarianism:

http://theveganoption.org/2017/06/29/veghist-ep14-diet-reform-consumerism-lebensreform-ramachandra-guha-adam-shprintzen-sabarmati-ashram/

It deals with other consumerist vegetarians, like Chicago Universities’ vegetarian athletics team, and the support for vegetarianism amongst strands of the physical culture movement. As well as movements in the rest of the world – the “back to nature” movement in Europe, the French anarchist vegans, and Gandhi’s activism in India.