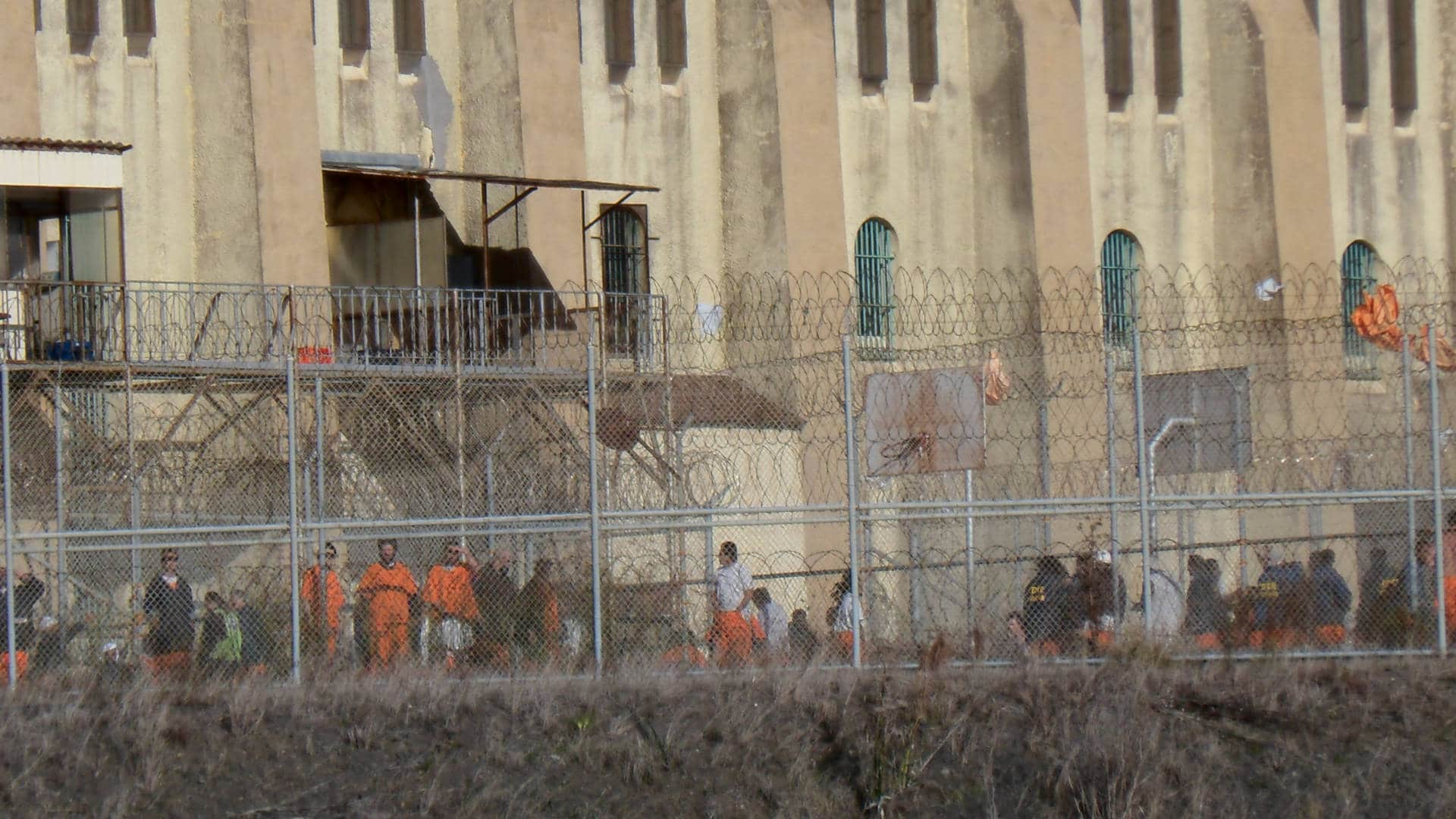

Politicians in the United States have chosen for decades to spend trillions of dollars to manage poverty, addiction, and homelessness via policing and prisons. As a result, around 20 percent of the world’s incarcerated people are held in one of the world’s wealthiest nations — despite it containing less than 5 percent of the global population. And as millions of people have been forcibly cycled through America’s punishment system over the years, it has etched deep harms into their bodies, psyches, and social lives — harms that continue to haunt them long after they have been released from custody.

The harms of incarceration include economic costs, long-term housing and employment disadvantages, social injury, psychological trauma from rampant human rights abuses, and chronic health care neglect. One measure of the collective impact of these harms is life expectancy: A study of parolees in New York estimated that, on average, incarcerated people were deprived of two years of life expectancy for each year they were locked up; another estimated that a 45-year-old who has been incarcerated in the U.S. can expect to live four to five years less than they would have had they never been imprisoned.

But numbers like these only scratch the surface of the damage incarceration leaves in its wide-rippling wake. That’s because biomedical and social conditions are always intertwined, which means that they implicate not just individuals but communities. As a result, harms inflicted on incarcerated individuals undermine the health and safety of their families, neighborhoods, counties, and, ultimately, the whole country. America’s mass incarceration problem is a massive public health threat to us all.

Millions of families who have endured the incarceration of a loved one are already intimately acquainted with this fact. Recent research found that siblings, children, and parents of the incarcerated themselves lose 2.6 years of life expectancy relative to peers who have not had family members taken away by the American legal system. Notably, these human costs fall heaviest on communities of color, especially Black communities, whose ongoing systematic legal and economic oppression effectively amounts to a race tax, paid not just in dollars but also in years of life.

But in a country where there are as many people who live with criminal records as there are people with college degrees, the harms of incarceration don’t stop at the family; neither do they stop with overpoliced communities of color. Recently, public health researchers have begun using the tools of epidemiology and econometrics to trace the ways carceral injury spreads to the general public, and to document the extent of its reach. Two important studies published in the last year, for example, show that higher incarceration rates drive significant increases in community-wide mortality –– due to causes including infectious disease, chronic lower respiratory disease, overdose, heart disease, diabetes, and suicide.

This is because, as carceral-community epidemiology makes clear, incarcerated people are always in biosocial interrelation with outside communities, such that correctional health and community health cannot be effectively studied or addressed in isolation from one another. The consequences of abusive conditions in jails and prisons therefore inevitably boomerang back to harm the rest of society. So, for example, when incarcerated people are subjected to overcrowding and neglect that foster the rapid spread of infectious diseases, jails and prisons are made into epidemic engines that multiply and spread sickness and death throughout broader communities.

|

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive. |

The Covid-19 pandemic has put this reality of carceral-community epidemiology into stark relief. Several of the earliest Covid-19 outbreaks in the world occurred in Chinese prisons. By the end of February 2020, Wuhan prisons, for example, contained nearly half of the city’s known Covid-19 cases. Soon thereafter, outbreaks began appearing in jails and prisons worldwide. Public health experts sounded alarms that the world’s largest system of incarceration — America’s — posed a major threat to public health and global biosecurity. Unfortunately, U.S. public health officials and policymakers responded by mostly turning a blind eye.

As a consequence, in March 2020, one of the biggest outbreaks in the U.S. began at Cook County Jail in Chicago. Within weeks, nearly 16 percent of the thousands of community cases statewide in Illinois were attributable to spread from the jail, according to analyses conducted by a colleague and myself. By April 2021, 661,000 cases of Covid-19 had been documented inside U.S. jails and prisons. Today, due to data obstruction by prison administrators and dysfunctional reporting systems, no one knows for sure how many people have become sick or have died inside these institutions. But one thing is certain: However many infections and deaths there have been on the inside, carceral facilities have given rise to many times more on the outside. Millions of cases and tens of thousands of Covid-19 deaths across the U.S. have been driven by outbreaks that spread from jails and prisons into surrounding communities.

This carceral boomerang effect is not new. Long before Covid-19, it had been observed in relation to HIV, tuberculosis, hepatitis C, influenza, and other infectious diseases. My colleagues saw it during prison-driven tuberculosis epidemics in post-Soviet Russia, after a substantial increase of the Russian incarceration rate in the 1990s helped fuel an explosion of drug-resistant tuberculosis across Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Studies have also repeatedly demonstrated links between incarceration rates and community-wide tuberculosis outbreaks in Brazil. And a 2020 study in Paraguay warned that higher incarceration rates were fueling TB spread within prisons that, in turn, threatened wider public health and jeopardized the nation’s tuberculosis control system.

By incubating and spreading disease, mass incarceration has long undermined public health for everyone. What’s new with Covid-19, then, is not how incarceration is harming us but rather the enormous scale and rapid pace at which it is doing so. And despite claims by politicians who seek to avoid responsibility for inaction, none of this was unforeseen.

Fortunately, as the more infectious omicron variant intensifies an ongoing pandemic, there is an immediately accessible solution to the flood of disease spread by mass incarceration: Release the hundreds of thousands of individuals who evidence shows pose no threat to public safety. Their continued confinement clearly makes no one safer.

If President Joe Biden, Attorney General Merrick Garland, the U.S. Congress, state governors, mayors, judges, sheriffs, and prison administrators find the courage to fulfill their duty to protect the public, thousands of needless deaths can still be prevented. Collectively, these officials have a vast array of policy options at their disposal, including executive orders; commutations; expanded use of clemency; federal, state, and local court orders that can release thousands of people; and changes to policing policies that can stop senseless arrests for low-level alleged crimes. Officials — from the local to the federal level — must stop feigning helplessness and use the levers of power available to them.

But the American public cannot wait on politicians who have — on a bipartisan basis — repeatedly exploited the politics of “crime paranoia,” insisted on pointless punishment, and prioritized political points over constituents’ lives. To confront our national carceral problem, we will need to build broad coalitions of activists, criminalized communities, labor unions, prison and jail staff, public defenders and prosecutors, public health and health care workers, and millions of formerly and currently incarcerated people. We must collectively force lawmakers to reject tepid incrementalism and to embrace bold steps to end mass punishment. These steps must include large-scale decarceration coupled with investments in systems for successful reentry, such as guaranteed housing, health care, and basic income, as a basic matter of both ethics and public health.

The abolition of America’s incarceration system –– and its replacement with infrastructures of support that are far more effective at preventing violence –– must be a centerpiece of sustained efforts to rebuild U.S. public health and global pandemic preparedness. Rather than spend some $200 billion each year on policing and punishment that inflict harm on the entire country, America’s lawmakers must redirect public investments towards building the systems of equality, economic security, and care required to ensure genuine public safety for everyone.

Eric Reinhart is an anthropologist of policing, prisons, and public health, a psychoanalyst, and resident physician at Northwestern University. He is also a lead researcher in the Data and Evidence for Justice Reform program at The World Bank Research Group. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of The World Bank. @_Eric_Reinhart

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

All of your arguments, albeit familiar, we’re cogent and well argued. May I gently suggest that you missed the one most cogent?

You failed to include in your language any suggestion that prison is a moral blight. I know that you will just say that it is not within the purview of an economist to recruit such language assuming that you are suggestible to the notion that there is a moral dimension to mass incarceration in the first place.

If it is a moral blight, then the only language that should be used, the only language that could ever possibly be effective is language which recognizes and addresses this hard fact.

Consider other examples. Would you begin to make an argument against slavery or somebody’s active program of ethnic cleansing by starting with a list of deleterious economic consequences, or by carefully explaining how such institutions cause the rest of society to be more susceptible to disease?

I should like to make the urgent case not just for better language but better framing. Many over the years have brilliantly written about prisons broader costs and the depredations visited upon the imprisoned and formerly imprisoned. No one really pays attention at this point even if it can be a reliable sinecure for a few academics.

Have you considered the possibility that there is a relationship between American prison on the one hand and our inability or unwillingness to recognize that the problem fundamentally owes to a debasement.