Randall Jordan-Aparo, Darren Rainey, and Latandra Ellington are not household names. But like Michael Brown, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor, they were killed by law enforcement officers.

Not police officers, but corrections officers.

No dataset tracks the number of people in prison who die at the hands of those hired to keep them safe. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that between 2012 and 2016 — the most recent data available — approximately 128 state and federal prisoners died from homicide or accidents per year. The agency does not separately report incidents involving prison staff versus prisoner-on-prisoner violence. This is also likely to be an undercount since many investigations of suspicious deaths in prison are done internally by corrections departments.

In the absence of detailed and reliable data, what we do have are accounts of sadistic and retaliatory violence by prison guards against people in prison. According to investigations by the Miami Herald, corrections officers gassed Randall Jordan-Aparo as he begged for help, likely killed Latandra Ellington for speaking out about sexual abuse, and scalded Darren Rainey to death in the shower.

Just as insidious are routine “use of force” incidents that are clearly excessive. In June, for example, Florida corrections officers beat Christopher Howell to death while removing him from his cell after he reportedly “refused a command.”

Although it doesn’t receive the same national media attention as police brutality, there is an ongoing humanitarian crisis in U.S. prisons. As a sociologist, I have researched and written extensively on the history of state prisons — which hold two-thirds of people incarcerated in the U.S. — and the causes of mass incarceration.

Similar to excessive police force, brutality by prison officers is part of systemic state violence against people of color, and Black people specifically. As I explain in my book, “Building the Prison State: Race and the Politics of Mass Incarceration,” racist ideas about irredeemable “criminals” helped convince state legislators to spend approximately $70 billion to build 1,000 prisons in the 1980s and 1990s. By 2007, operating expenses for state corrections departments had increased 250 percent to $56 billion a year.

After the election of President Barack Obama, a wave of White racial resentment galvanized by the Tea Party movement swept business-backed fiscal conservatives into state houses across the country. As promised, governors and state legislatures began to defund a variety of state agencies and programs. Where politicians had once protected already underresourced departments of corrections from spending cuts, they now began to delay maintenance on prison facilities and strip state prisons of educational programs down to what one Florida state legislator called “bare and naked incarceration.”

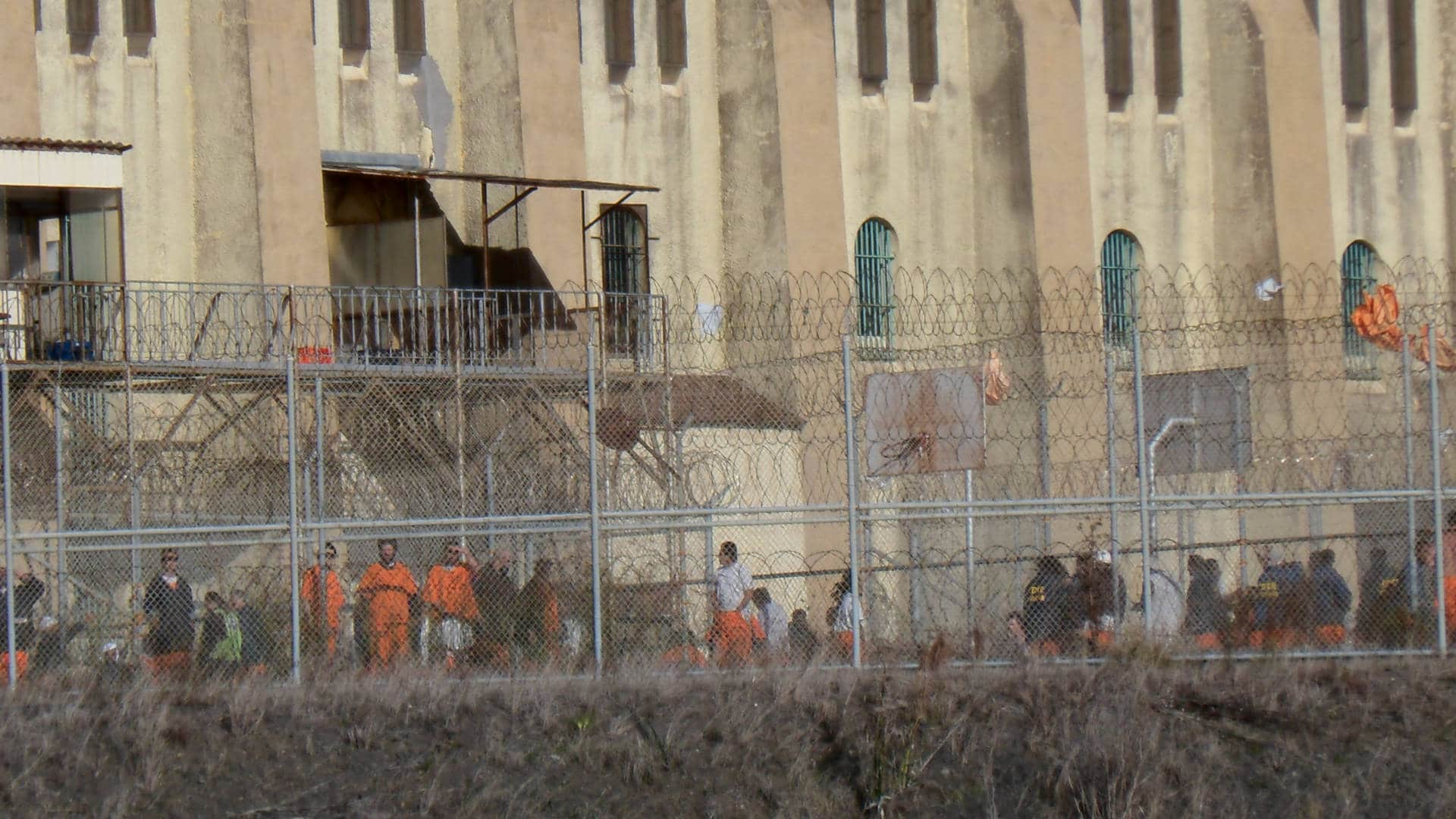

As a result, state prisons today are severely underfunded, understaffed, overcrowded, and deteriorating.

In Florida, the state I have researched most extensively, fiscal austerity hit the Department of Corrections early, under the leadership of Gov. Jeb Bush, and continued long after he left office in 2007. The Miami Herald chronicled the decline. In 2012, after five years without a raise, the state cut thousands of corrections officer positions by moving from an eight- to a 12-hour shift. By 2017, the Herald reported, the state could not fill 2,500 corrections officer positions left open because of high turnover and low pay. And, in 2019, the new Florida Department of Corrections Secretary warned that years of budget cuts and legislative indifference have created a system at the brink of a “death spiral.”

The consequences of understaffing are compounded by prison overcrowding. According to an analysis by ProPublica of federal data, between 2011 and 2018, 32 states closed one or more prisons, without corresponding reductions to the state’s overall prison population. This year, as coronavirus hit, at least 16 state prison systems — in every region except the Northeast — had seriously overcrowded prisons, according to local news reports.

Most departments of corrections contract with private companies to provide health care in state prisons. The rising cost of medical care and reduced state budgets squeezed these companies’ profit margins. As a result, the existing barely adequate health care in prisons deteriorated. At Ely State Prison in Nevada, for example, there was no full time physician on staff for 1,000 male prisoners. According to one medical expert, the medical neglect he saw amounted to a “callous disregard for human life and human suffering.” Since 2010, courts have ordered at least 10 state departments of corrections to fix substandard health care in the states’ prisons. In 2018, a U.S. District Court fined the Arizona Department of Corrections for “not taking its obligation seriously” as people in prison continued to die from medical neglect.

Prison overcrowding, inadequate prison health care, and a lack of infrastructure to manage the outbreak of disease has led to an alarming number of Covid-19 cases in state prisons. In San Quentin State Prison, just outside of San Francisco, more than one-third of prisoners have tested positive for Covid-19. According to The New York Times, in mid-June the five largest known clusters of the virus were inside correctional institutions.

Since the first week of May when prisons recorded a high of 87 prisoner deaths, as of mid-July every week on average 42 people die in prison of Covid-19.

|

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive. |

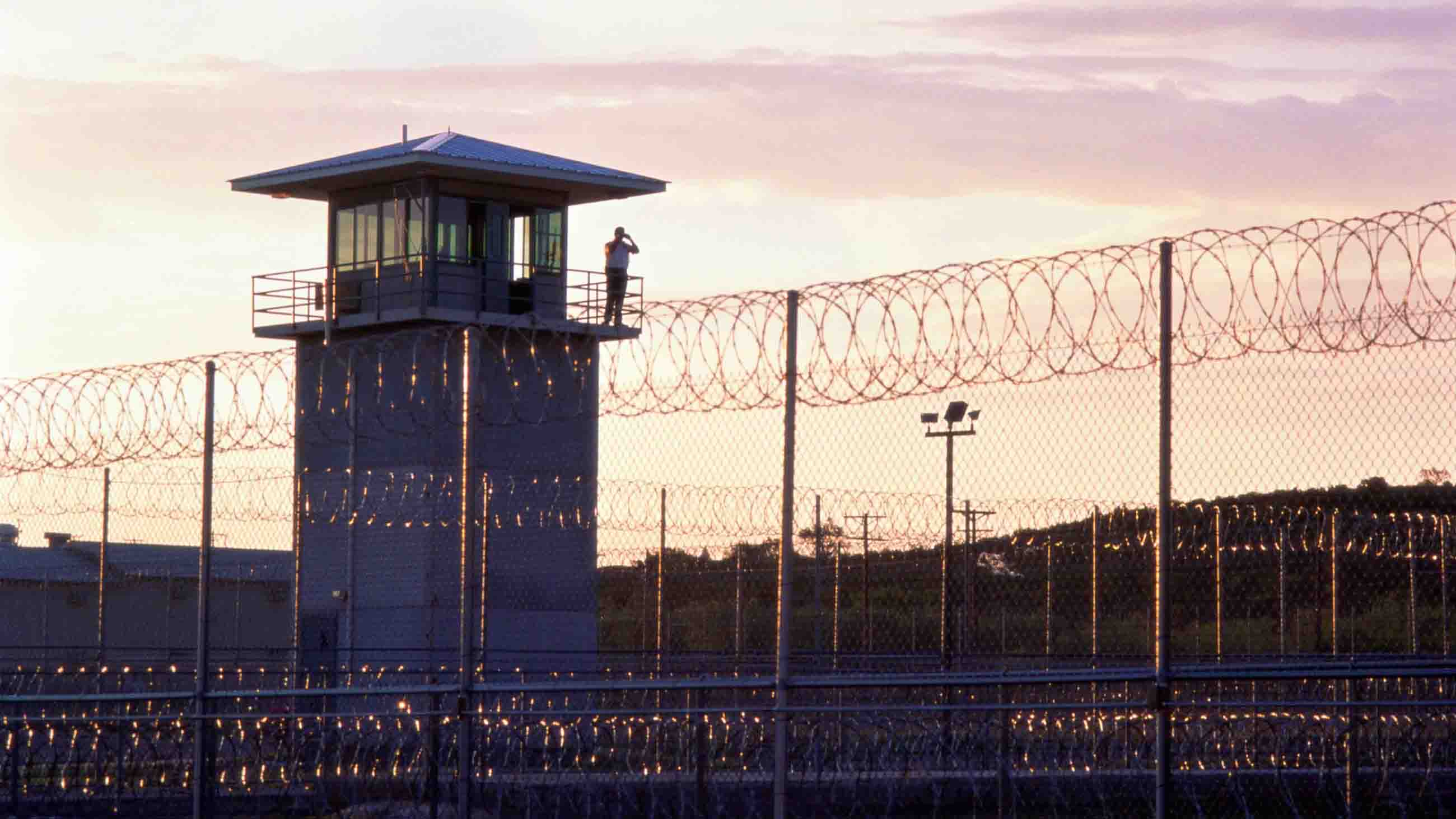

When prisons are understaffed, offer no programming and provide inadequate mental health care, maintaining order becomes more difficult. The use of solitary confinement increases. Resentment builds. Studies show that officers who work in chaotic and hostile work environments are more likely to adopt an “us vs. them” mentality and resort to retaliatory violence.

Prison officers’ acts of violence are often not reported. The blue code of silence that people associate with police applies equally to corrections officers. Prison staff that come forward are threatened and harassed. And, even more than police departments, prisons are not transparent. It is often only through local news media investigations that we hear these stories.

Corrections officers are rarely held accountable through civil lawsuits or criminal prosecution for their acts. The Miami-Dade County prosecutor Katherine Fernandez Rundle, who faces a real challenger in the upcoming primary for the first time since she was elected in 1993, declined to prosecute the prison officers who locked Darren Rainey in a scalding hot shower and left him there to die. The family of Rainey, a middle-age Black man with a diagnosed mental illness, later settled a civil rights lawsuit against the Florida Department of Corrections for $4.5 million.

Governors and state legislators have little political incentive to improve prison conditions. Sadistic, violent, and other unconscionable acts by corrections officers against people in prison don’t provoke the same public outrage as police murders of people in their homes and communities. Under the system of mass incarceration, those we have marked as “criminals” are denied not only their civil rights but their humanity.![]()

Heather Schoenfeld is an associate professor of sociology and law at Boston University. She is the author of “Building the Prison State: Race and the Politics of Mass Incarceration.”

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.