Kidney Dialysis Is a Booming Business. Is it Also a Rigged One?

Jo Karabasz knew her dialysis clinic well. Before switching to at-home treatment this summer, the former high school English teacher spent five and a half years visiting some of the dozens of DaVita dialysis clinics that dot the Northern California landscape. Her beige chair in the front corner of one clinic, where she attended appointments three times a week, quickly became her home away from home.

Since she was diagnosed with kidney failure in 2015, Karabasz has had around 820 in-center treatments, where a hemodialysis machine does the job her kidneys no longer could, filtering waste and excess fluid from her bloodstream. (She says she nicknamed her machine “Rocco, My Robot Kidney.”) Each treatment takes about four hours, which translates to around 4.5 months of Karabasz’s life spent in a dialysis clinic chair.

PROFIT & LOSS: THE COMPLETE SERIES

Intro | The Market | The Conflicts | The Disparities | The Waiting | The Alternatives

Holidays, wildfires, earthquakes — she says none are as important as her dialysis. Even a single missed dialysis treatment can create major health problems. If Karabasz were to miss two treatments, she could be dead before the third, as fluid would accumulate in her body and make it hard to breathe. In her last days, she could experience vomiting and confusion before her heart eventually stopped beating.

Karabasz says she’s handled a lot in her 58 years of life, but when it comes to her dialysis, she needs things to go smoothly. “Just don’t fuss with me,” she said.

So when one of the DaVita staff told Karabasz in the spring of 2019 that a new California bill could jeopardize the financial assistance she received from the American Kidney Fund (AKF), the nonprofit that helps to pay for her treatments, she felt the floor drop out from under her. “I just sat there in stark terror. Like, you have got to be kidding. Why are they doing that?” Karabasz said. “Why does the California Legislature care if the Kidney Fund helps me?”

They cared, proponents of the bill say, because they believed companies like Denver-based DaVita were gaming the system. Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 290 (AB 290) in October 2019. The bill requires dialysis centers to charge Medicare rates, or a rate determined by a dispute resolution process, for those receiving financial assistance from the American Kidney Fund. It also mandates that the charity furnish the names of all the people it is supporting to insurers. Shortly after the bill passed, Karabasz received a letter from the AKF saying that it would no longer be paying her premium assistance because it viewed AB 290 as being in conflict with its federal operating guidelines.

According to a January 2019 press release from legislator Jim Wood, the Santa Rosa Democrat who introduced AB 290, the bill was designed specifically to prevent companies like DaVita from “increasing their already excessive corporate profits through a scheme to bankroll patients’ health care premiums.” Democratic Sen. Connie Leyva proposed a similar bill in 2018 that was vetoed by then-Gov. Jerry Brown.

The scheme, according to Wood and other critics, works something like this: Nearly everyone in the U.S. with end-stage renal disease is eligible for coverage by Medicare, even if they are under age 65. The federal program pays a fixed cost of about $240 per treatment. Patients receiving Medicare pay an annual deductible, after which they continue to be responsible for a 20 percent co-payment, or about $48, for each visit.

Patients with private insurance, however — including those with health benefits paid for by their employers — are a different story. Those insurance companies must negotiate payments with for-profit dialysis centers, and research has suggested that the centers have an edge in those negotiations — one they use to jack up prices. One research letter, published last year in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Internal Medicine, found that private insurers paid, on average, over $1,000 per treatment — roughly four times Medicare’s fixed costs.

One possible reason: More than 80 percent of dialysis patients receive their treatments from either DaVita or Fresenius Medical Care, which is headquartered in Germany, giving the two companies upwards of 80 percent of the $24.7 billion American dialysis market — and significant influence over the prices charged to private insurers. What’s more, both are widely known to donate hundreds of millions of dollars to the American Kidney Fund, covering the vast majority of the nonprofit’s budget. That’s a problem, according to Wood. With the help of the American Kidney Fund, after all, more patients are able to stay on private insurance longer, so both companies have an incentive to keep the AKF well-funded. More patients with private insurance means DaVita and Fresenius can bill much higher prices for their dialysis services — and pad their own bottom lines.

According to Wood, for every dollar DaVita or Fresenius donates to the American Kidney Fund, they get roughly $3.50 in return from private insurers. No wonder, then, that the two dialysis giants, which together earned about $2.2 billion in net income in 2019, reportedly donated $247 million to the nonprofit organization in 2018 — roughly 80 percent of the fund’s annual budget that year. (AKF’s own financial documents do not name the companies outright, instead referring to two unnamed corporations. When asked to confirm the identity of these donors, Tamara Ruggiero, a spokesperson for the organization, said the AKF was barred from doing so by rules established by the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services — ironically to “ensure that patients are not unduly influenced in their choice of dialysis providers.”)

Wood has called this an all-out scam, but Fund representatives have pushed back against such characterizations, saying that the new law would make it impossible for them to aid California residents. Only an 11th-hour preliminary injunction — granted in December of 2019 by a U.S. district court in response to motions from the Fund, as well as from DaVita and Fresenius, among other petitioners — saved Karabasz’s monthly assistance.

Representatives of both Fresenius and DaVita declined repeated requests to make company officials available for an on-the-record interview for this story. In a prepared statement supplied by Alicia Patterson, a DaVita communications manager, the company suggested that Wood’s bill would deny thousands of Californians crucial health care assistance. “We will continue to advocate against this harmful law, while at the same time remain focused on providing high-quality care for our patients,” the company said. And in a statement attributed to Fresenius spokesperson Brad Puffer, that company said it aims to provide care to all patients regardless of insurance provider, and that the injunction blocking implementation of AB 290 was instrumental in allowing patients to continue accessing the care they need. “The ongoing focus on this issue does nothing to help improve overall patient care,” Puffer added, “and our goal to help more people gain access to transplant and home dialysis treatment.”

No final ruling on the legislation has yet been made, leaving the ultimate fate of the American Kidney Fund’s financial support in California in limbo — something that LaVarne Burton, the president and chief executive of the American Kidney Fund, suggests is part of the problem. Burton said that her organization had repeatedly asked the legislators, “If you don’t want the American Kidney Fund to assist these patients, what are you going to do to make sure that they get access to health care?

“There was never a plan,” she said.

For patients like Karabasz, these concerns are far removed from the ongoing, immediate need for dialysis. Karabasz says she doesn’t deny that DaVita might be benefitting from their donations to the Kidney Fund, but then, so is she. And she could not, she insists, afford her insurance premiums without their help, meaning that losing American Kidney Fund assistance would be a matter of life and death.

Health economist Paul Eliason of Brigham Young University argues that remedying the conflicts of interest inherent in the relationship between the Fund and for-profit dialysis clinics would clearly benefit society at large in terms of lower health care costs, at least in the short-term. But he added, it remains to be seen whether these conflicts actually harm patients.

“I do think that by limiting profits to these companies, you’ll actually probably see less growth of the big chains — DaVita, Fresenius — in California,” Eliason said. “And that’s going to be good in some ways and bad in some ways. I think that will probably mean there will be less access to care and patients may have to travel farther and be treated in more crowded facilities.”

In 2016, nearly 125,000 Americans started treatment for end-stage renal disease. Whether due to a genetic disorder like polycystic kidney disease or the result of damage from diabetes and high blood pressure, a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease means that the kidneys struggle to filter waste and extra water from the blood. Until the kidneys fail completely, many people have no symptoms that anything is wrong. At this stage, chronic kidney disease can only be diagnosed by a blood or urine test.

For Bernard Zachary, 51, of Modesto, California, who spent his adult life working in construction, heading to the doctor when he was feeling fine seemed like an invitation for trouble. “I was always working and I was always told to get a doctor’s appointment, and I didn’t want to create a doctor bill or anything,” he said.

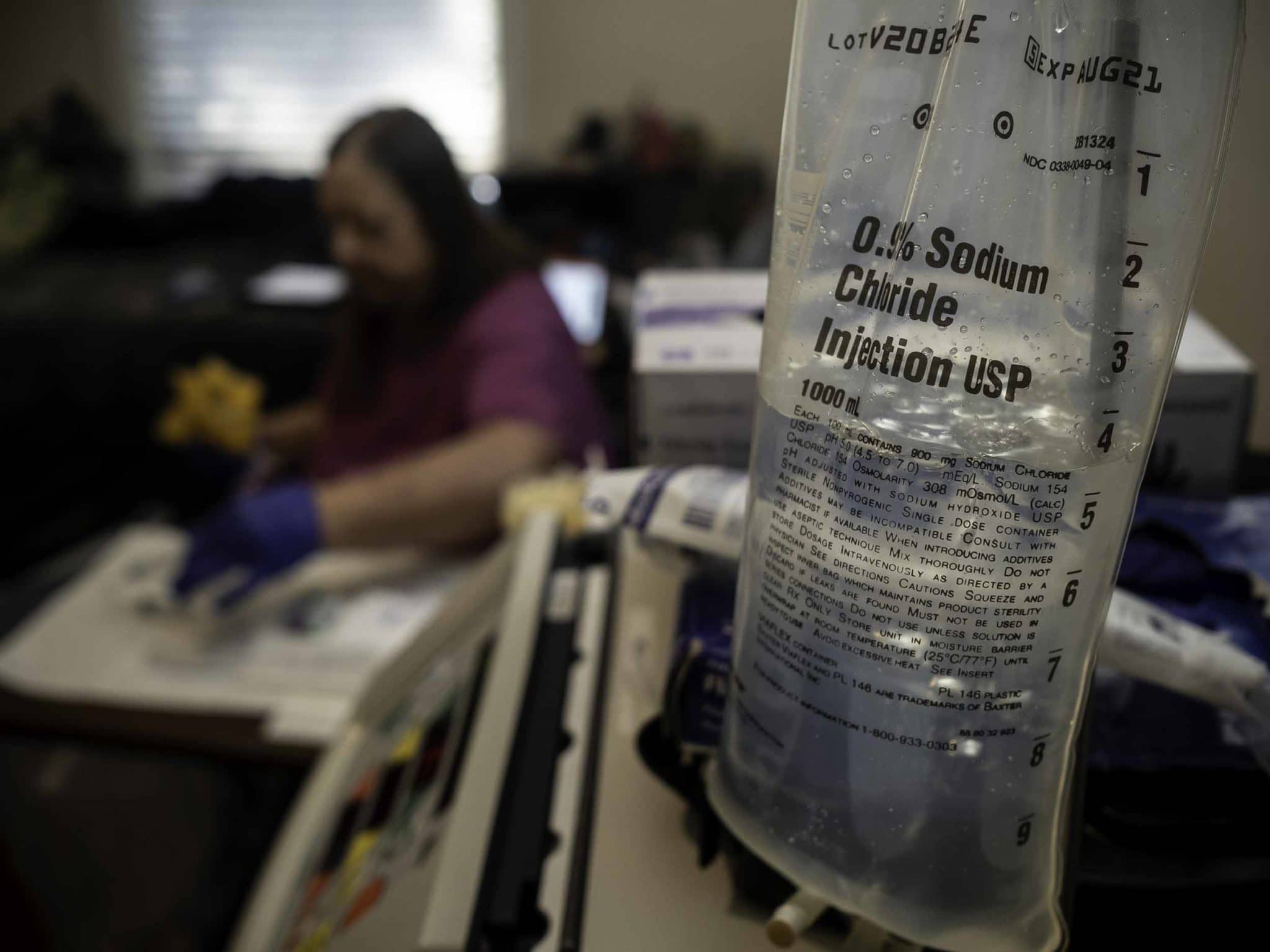

But in February 2016, after dealing with persistent swelling in his feet, Zachary headed to the hospital. Tests showed he had high blood pressure and that his kidneys had failed. Zachary needed dialysis right away. He opted for a treatment called peritoneal dialysis, which uses the blood vessels in the abdomen and a cleaning fluid called dialysate. This allows Zachary to do his treatments at home every night while he sleeps, rather than going to a clinic several times each week.

DaVita provides the equipment and medical support for his dialysis.

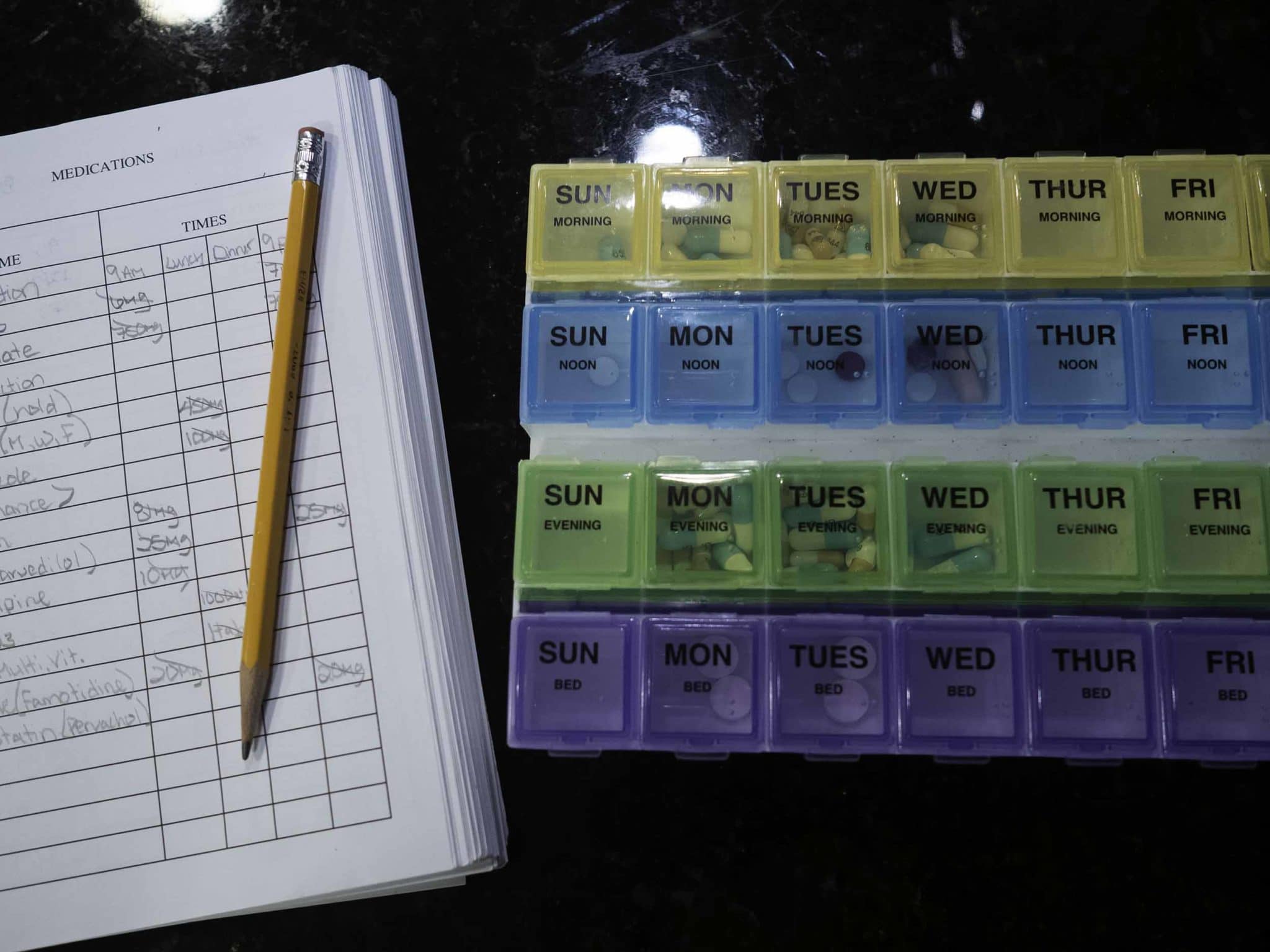

Studies suggest that somewhere between 23 and 38 percent of people with kidney failure “crash” onto dialysis like Zachary, meaning they start it in an unplanned way, with little or no prior care from a kidney specialist. Many of these individuals are too sick to work full-time at this point. Others, like Zachary, could potentially remain employed but dialysis gets in the way. The physical labor of his construction job would dislodge his dialysis catheter, so he had to quit. Karabasz knew for years that her kidneys were failing and left her job preemptively to pursue tutoring with her husband. As it does for so many Americans, the loss of their jobs meant the loss of employer-sponsored health insurance.

Indeed, because end-stage renal disease was so often accompanied by unemployment, Congress passed a law in 1972 that made patients who also qualified for social security eligible for Medicare three months after diagnosis, even if they were under 65, the age when Medicare typically kicks in. An amendment to a later act required that everyone with end-stage renal disease use Medicare as their primary insurance 30 months after diagnosis. Given that only one-third of those on dialysis survive for five years, those first 30 months are where companies like DaVita and Fresenius earn their profits — and it’s the key window they spend millions fighting for. According to data supplied by AKF, roughly a quarter of its insurance assistance recipients were on employer-provided or otherwise private insurance in 2019.

At first, Karabasz and her husband managed to scrape together nearly $835 per month to continue with her existing Kaiser Permanente insurance from teaching, but the financial strain caused her depression to spiral. Maybe, she says she began thinking, her family would be better off without her. A social worker at her dialysis center noticed her low moods and increasing despondence, and Karabasz eventually confessed everything. The social worker paused, then asked if she’d heard about the American Kidney Fund.

Founded in 1971, the AKF began as a small group of people raising money for a friend who needed help paying for dialysis. In the nearly half-century since, it has become one of the country’s largest nonprofit organizations, providing funds to dialysis patients to defray the costs of insurance premiums and other associated expenses. To date, Burton says, the organization has been able to assist everyone who meets its eligibility requirements, which is currently households whose income doesn’t exceed expenses by more than $600 per month, and whose assets total no more than $7,000, not including a patient’s primary vehicle and home, retirement accounts, and basic household items.

Karabasz easily met those requirements and began receiving help almost immediately. To her, it changed everything. “I was very grateful to them and felt confident and secure with them,” she said. “So it seemed that getting help to pay that bill was what was going to work for me. Thank God that that help was available.”

Karabasz is one of more than 80,000 low-income Americans — 3,700 of whom are in California — who receive help from the American Kidney Fund each year. On the surface, the arrangement seems copacetic: a charity helping low-income chronic disease patients receive life-saving treatment. But both lawsuits and the California legislation have challenged this rosy view of the Fund and its work.

In the 1970s, when the AKF was founded, outpatient dialysis was fairly new and the industry was small. Medicare coverage expanded the number of people who could afford dialysis, and increases in the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension, along with an aging population, meant that the number of people who needed dialysis also rose. In 2018, more than 500,000 Americans were receiving some sort of dialysis treatment, according to data from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). At first, many providers were small and independently owned. Beginning in the late 1990s, two early leaders in dialysis, DaVita and Fresenius, began to buy out smaller clinics.

University of Chicago economist Thomas Wollmann, photographed in a recent video call. Wollmann says he knows of one area in Texas that has two dialysis clinics right next to each other. “If one buys the other one, that’s devastating to competition,” he said, “because it’s basically a merchant monopoly.”

By gobbling up individual clinics, one by one, the companies could avoid federal oversight of corporate mergers, which generally only kick in when an acquisition is valued over a certain amount. Before 2001, that threshold was $15 million. Today, it sits at $94 million.

The problem, points out University of Chicago economist Thomas Wollmann, is that dialysis clinics serve a local clientele. Plenty of competition in New York doesn’t tell you anything about the situation in South Dakota. Wollmann says he knows of one area in Texas, for example, that has two dialysis clinics right next to each other but nothing else for 60 miles in any direction. Each clinic may only be valued at $3 million or $5 million, which is far below the number the Federal Trade Commission is worried about.

But “if one buys the other one, that’s devastating to competition because it’s basically a merchant monopoly,” Wollmann said. According to a recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper he authored, of the 4,000 facility acquisitions dialysis providers proposed between 1997 and 2017, about half were exempt from reporting.

As large chains, DaVita and Fresenius have more ability to negotiate prices down for drugs and other needed supplies. This has increased their profit margins and made them able to buy up even more mom-and-pop clinics. Today, the two companies own some 70 percent of U.S. dialysis clinics.

The dramatic drop in competition, research suggests, was amplified by declines in quality of care. An analysis of 1,200 acquisitions over 12 years, conducted by Brigham Young’s Eliason and colleagues, showed that large chains replaced high-skilled and high-cost nurses with cheaper technicians and increased the patient load of each employee by 11.7 percent. That analysis, published in November 2019 in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, showed that the number of patients treated at each dialysis station also rose by 4.5 percent. As a result, patient care quality dropped. They found fewer kidney transplants, higher rates of hospitalization, and lower rates of overall survival among dialysis patients at for-profit clinics.

“What we’re seeing in the market, I think, does have an influence on the care patients receive,” said Kevin Erickson, a nephrologist and health policy expert at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Dialysis centers acquired by large chains, Eliason and his colleagues’ research found, also used larger amounts of expensive, injectable drugs used to treat anemia, as most chronic kidney disease patients have a reduced ability to produce new red blood cells. Like all drugs, these injectables can have side effects, including increased risk of heart attack and death, especially when patients receive too high of a dose. According to a 2005 financial document from DaVita, these injectables, along with vitamin supplements, formed 40 percent of the company’s total dialysis revenue. Eliason and colleagues found that the doses of one such drug, Epogen — or epoetin alfa, as it’s called generically — increased by 129 percent after an independent clinic was acquired by a large chain.

“We’re able to look at the same patient in the same facility before and after it’s acquired by one of these big companies, and we see that for that patient, their [Epogen] doses just skyrocket,” Eliason said.

But in 2011, when Medicare implemented a system that lumped payment for dialysis in with the drugs used during treatment (thus removing the financial incentive to over-prescribe), dosing of epoetin alfa plummeted.

The need for and use of expensive prescription medication is just one reason that treating end-stage renal disease is so costly. In 2018, according to the USRDS, Medicare paid $31.3 billion in fee-for-service expenditures — where the government pays providers separately for each service provided — to treat the more than 500,000 dialysis patients in the U.S. Although kidney failure patients comprise just around 1 percent Medicare’s fee-for-service population, they represent 7.2 percent of such Medicare expenditures. The high medical costs of people with kidney failure is one of the reasons that Burton suspects the insurance industry supported AB 290, since it would mean they had to pay less to dialysis centers. And of course, offloading expensive kidney disease patients onto government insurance would increase their own profit margins.

When insurers set their premiums, she said, “they’ve already factored in that they will have people with kidney failure, with cancer, with heart disease who are more expensive. If they can factor that into their premium and then get those people off of their insurance, their profits go up even more.”

But it was the use of American Kidney Fund assistance to potentially bolster the profit margins of the dialysis companies that first triggered the fight in the California legislature.

There are currently more outpatient dialysis clinics in the United States than there are Burger King restaurants, and the prevalence of these clinics confirms to critics like Wood that dialysis is a massive and, from his perspective, inordinately profitable business. “Profiteering at the expense of patients and the public is immoral and it should be seen only for what it is — a self-serving scam,” he noted in a press release in January of last year.

In that release, Wood stated that the donations DaVita and Fresenius make to the American Kidney Fund are used to steer patients toward higher-premium commercial insurance plans. Since these insurance plans give dialysis clinics like DaVita and Fresenius more money per treatment than Medicaid and Medicare, getting as many privately insured patients as possible directly benefits their bottom line.

Erickson had a similar perspective. “My guess is there is a large, strong incentive for any dialysis organization, whether it’s profit or nonprofit,” he said, “to attract patients who are privately insured, where they can potentially receive those higher private insurance reimbursements for up to 30 months.”

It doesn’t take a lot of people to make a big difference. A 2019 analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine by researchers including Gerald Kominski, a health policy professor at UCLA, showed how even a small number of privately insured patients could bolster the industry. In 2017, commercial insurance paid DaVita an average of $1,041 per dialysis treatment, compared to $248 for government insurance. That adds up to $148,722 each year for a privately insured patient versus $35,424 for one on Medicare or Medicaid, the study showed. Although this study didn’t look into financial assistance from the AKF and why dialysis corporations might donate, Kominski suggests that the motivation is apparent. “My guess is that they get a very large return on their investment,” he said, “— many, many dollars back for every dollar they spend in premium support.”

Having to pay providers so much extra money for the same care should leave commercial insurers in the red, but that’s not the case, Kominski explains. Private insurance also wants to maximize profits, but they can use different strategies to increase revenue, such as increasing premiums. Reimbursing at higher rates isn’t a problem for commercial insurers because they don’t face the same pressures as public insurance to keep costs low. Instead, they can just extract more money from their customers in the form of higher premiums.

Noting the rising cost of health care as a persistent problem, Wood’s communication director, Cathy Mudge, wrote in an email that the assembly member has worked on other legislation to curtail it. With AB 290, she wrote, the aim is to rein in the excessive profits that dialysis corporations like DaVita and Fresenius are making at the expense of the general public.

The legislation would force everyone to play by the same rules by requiring recipients of American Kidney Fund grants to have their dialysis reimbursed at Medicare rates, even if they have private insurance. Although AKF says dialysis clinics have no influence over which patients receive its assistance, a whistleblower lawsuit unsealed in Massachusetts in August 2019 supported Wood’s assertions that DaVita, Fresenius, and others were using AKF for their own financial gains. And with so much of the dialysis market controlled by these two large corporations, they don’t need to do very much to benefit from their AKF donations. Simple probability says that anyone on dialysis is likely to be served by a DaVita or Fresenius clinic because they control so many facilities, Eliason says.

Of AB 290’s stalling, Wood wrote in a statement provided to Undark: “This injunction and the year-long delay of the court case are consequential because it emboldens the corporate duopoly of Fresenius and DaVita to continue to gouge the health care system to increase their profits.”

The high financial stakes of California’s efforts to regulate the dialysis marketplace have been apparent in the amounts spent by lobbyists. Records from the California Secretary of State showed that dialysis corporations forked over upwards of $110 million via the California Dialysis Council in 2018. The spending spree began with 2018’s Proposition 8, which sought to cap dialysis profits at 15 percent above the cost of care, and continued into the debate over AB 290. They provided even more by bankrolling an industry-backed group called Dialysis is Life Support, which created videos and ran ads on CNN and other outlets.

Kathy Fairbanks, a spokesperson for the organization, says that the companies were just looking out for their patients. When asked whether corporate lobbying could really be motivated by goodwill alone, Fairbanks suggested the question was “cynical,” adding that “if the end result is that patients will be better off with the defeat of AB 290, that really from our perspective, that’s the end goal.”

Whatever the reality, the relationship between the American Kidney Fund and major for-profit dialysis providers seemed destined for greater oversight in the passage of AB 290 — though the Fund and its supporters saw at least one avenue to fight back: When former President Bill Clinton signed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) into law, it included rules that barred treatment providers from waiving co-insurance and deductible costs for patients on Medicare or Medicaid, or providing “items and services for free or for other than fair market value,” while allowing for various exceptions. To ensure that grant-making organizations like the AKF didn’t run afoul of these new rules, the Fund asked the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General to review its practices. In a 1997 advisory opinion, the OIG stated that the Fund could continue to accept donations from dialysis providers as long as it didn’t use information about donation amounts, nor which company’s clinics a patient was utilizing, as criteria for distributing assistance. The AKF says it has strictly operated under this guidance since it was issued and does not provide the names of patients who receive assistance to its donors or to insurers.

When AB 290 required the AKF to provide a list of grantees to health insurance companies, Burton said this would directly violate the advisory opinion guidance and so they would have to stop helping California residents. “The legislature by their action gave us no choice,” Burton said. “In order to protect patients in California, and to protect the patients that we serve throughout the country, we had no choice but to go back and to file suit against the state of California.”

The problem with the 1997 guidance, according to Rep. Katie Porter, a congresswoman for California’s 45th District, is that the dialysis market looks vastly different now than it did back then. In a July 2019 letter, she urged Joanne Chiedi, then-acting inspector general for HHS, to suspend its guidance and conduct an investigation into the AKF’s relationship with dialysis providers. Some insurers already do know which of their customers receive premium assistance from the AKF, since the AKF directly pays the bills for some of its grantees. The organization says that this is done with patient knowledge and consent, unlike the list that would be required under AB 290. (The bill specifies that it would ensure its provisions are not in violation of any federal privacy law.)

In granting the preliminary injunction against AB 290 — two days before it was set to become law — Federal Judge David Carter of the Central District of California was apparently unconvinced. The state had not shown that American Kidney Fund assistance increases health care premiums, Carter held, nor had it shown any evidence of patient steering. The initial trial, scheduled for late spring, has been postponed and no final verdict has yet been reached.

All of this has left patients like 41-year-old Brian Carroll feeling caught between the AKF’s assistance and AB 290. Unable to work because of his kidney disease, a rare condition called focal segmental glomerulosclerosis that causes scar tissue to form in the kidneys, Carroll lost access to his private insurance. After going on Medicare and later seeking out his own secondary insurance, he was forced to move back in with his parents in December 2016 to afford his premium.

Carroll has since received a kidney transplant and hopes to soon be healthy enough to go back to work. While the assistance he receives from the American Kidney Fund will run out at the end of the month, he said, “every little bit helps.”

Although Carroll is grateful for the funding he’s received, the idea that DaVita and Fresenius can pad their bottom lines using the American Kidney Fund makes him livid. Unlike Karabasz, who blames AB 290 and those behind it for the uncertainty of her position, Carroll says some responsibility falls on the American Kidney Fund. “If you can still support 49 other states and dialysis patients, and you can’t support California, I don’t understand,” he said.

Even with the preliminary injunction in effect, Carroll says the fund had begun requiring more frequent paperwork to verify his income and dialysis status. Whereas he used to fill out forms once a year, he says he began having to complete the documentation every few months. “You always have that dark cloud of ‘Is this going to be the last time that they do this?’” he said reflecting on the assistance he’s received.

In DaVita’s emailed statement, the company said “Should Assembly Bill 290 be implemented, it will affect nearly 4,000 low-income, primarily minority, California dialysis patients who rely on charitable support to pay for their health care costs. We believe the law threatens to harm California citizens who need dialysis to survive and that it is unconstitutional; due to this we joined a legal challenge and are pleased the court issued a preliminary injunction preventing the implementation of AB 290.”

Erickson, meanwhile, argues that no decision around AB 290 will result in a perfect system. “As the government comes up with policies to try to regulate private insurance markets to keep prices down, there are trade-offs,” he said. “And, in this case, if a law like this does keep the prices of private insurance down, it might do so at the expense of some of the patients who would benefit from this financial support that they no longer have access to.”

Karabasz says she has no problem with DaVita making a profit. “I don’t have time for them to reorganize and rethink how it’s done,” she said. “I have two days. And if I don’t get my treatment in two days, my life is on the line.”

This series was supported in part by the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation.

Carrie Arnold is an award-winning freelance science journalist based in Virginia. In addition to Undark, her work has appeared with Scientific American, STAT, National Geographic, Wired, and The New York Times, among other publications.

Larry C. Price is a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning documentary photographer and multimedia journalist based in Dayton, Ohio. He previously produced award-winning photography and video footage for Undark’s Breathtaking series on air pollution, which won a George Polk Award for Environmental Reporting in 2018.

PROFIT & LOSS: THE COMPLETE SERIES

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Algo tendrá el agua cuando la bendicen.