Almost 90 percent of scientists believe that genetically modified foods are entirely safe. Yet, just 37 percent of the general public think these foods are safe to eat. Why are so few on board with the scientific consensus? Are they just anti-science?

In “Glyphosate and the Swirl: An Agroindustrial Chemical on the Move,” medical anthropologist Vincanne Adams deciphers competing claims about the history and epidemiological impact of glyphosate, the main ingredient in Roundup, the powerful herbicide patented by the agrochemical giant Monsanto that is commonly used to grow genetically modified foods. Depending on where you look for evidence, glyphosate either poses no harm to humans or is the root cause of a public health crisis. In the process of analyzing the uncertainty about glyphosate’s safety, Adams leverages the debate to interrogate what scientific consensus even means as a concept.

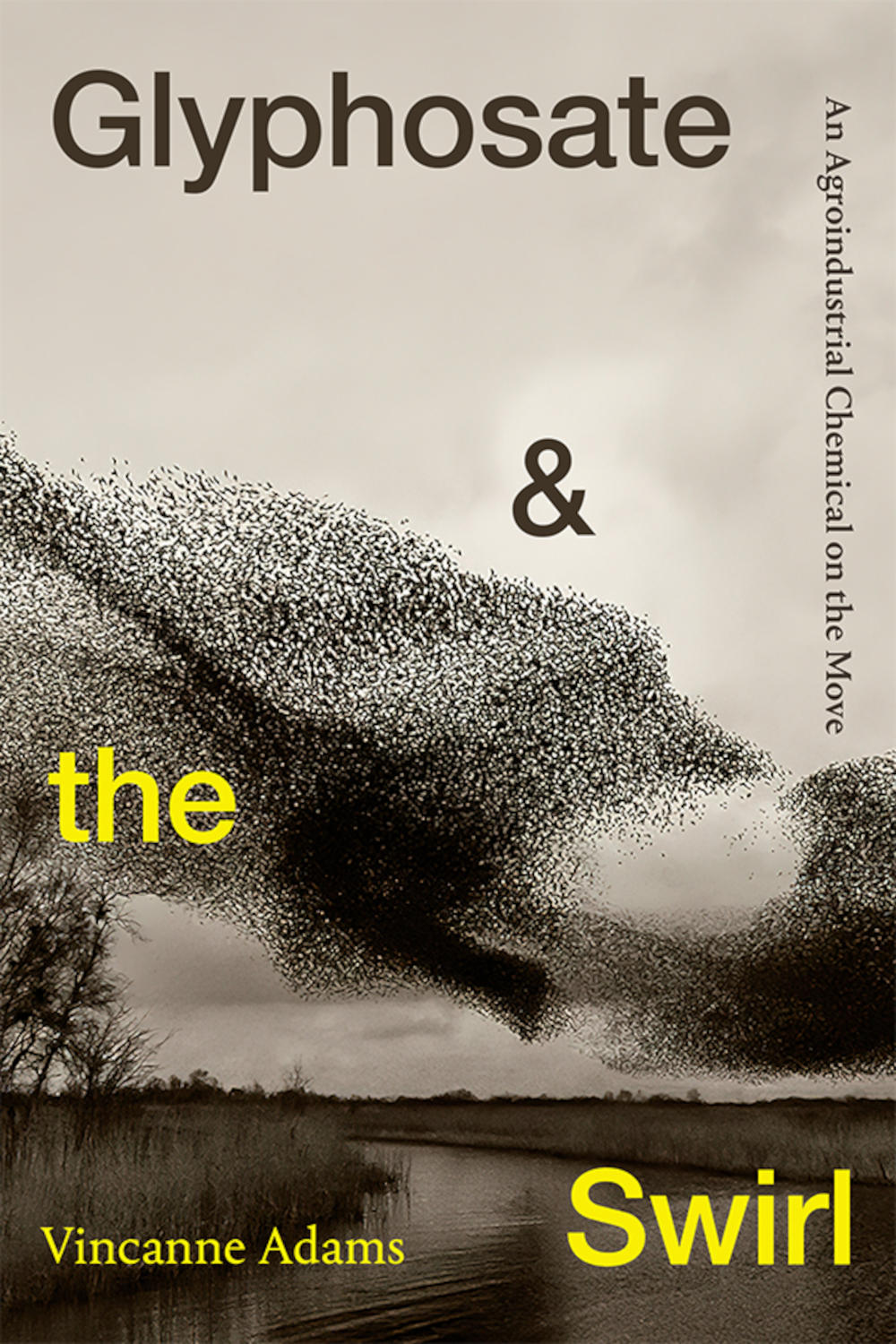

BOOK REVIEW — “Glyphosate and the Swirl: An Agroindustrial Chemical on the Move,” by Vincanne Adams (Duke University Press Books, 184 pages).

Even glyphosate’s origin story is contested, according to Adams, with one version crediting chemist Henri Martin with crafting the chemical in his laboratory in Switzerland in 1950. Glyphosate later made its way to Monsanto in the 1960s via a series of business acquisitions. In another telling, Monsanto scientist John Franz was working with several chemicals while trying to develop a water-softening product that could be repurposed as an herbicide. He found glyphosate to be particularly effective at killing plants by blocking a key metabolic process.

Monsanto began using glyphosate in the 1970s. Most herbicides at the time worked by creating a chemical barrier on the surface of the soil that killed weeds as they sprouted through. Roundup, however, is applied after weeds start to grow, and in contrast to other herbicides that selectively kill weeds but leave crops unharmed, farmers had to be careful with the indiscriminate effects of Roundup use.

Monsanto also began to invest in research on genetic engineering in agriculture and farming. Plants could be modified to ripen without softening, to have higher nutrient content, to resist frost, and to be tolerant to insects and viruses. Despite the company’s efforts to portray itself “as both defender of the environment and friend of farmers,” Adams writes, enhancements in nutrition, flavor, and size were marginal in its investment in genetically modified crops.

Instead, Monsanto focused on creating a genetic modification that would create plants that could withstand multiple applications of Roundup throughout the planting season. This enabled the company to make a fortune selling both seeds and herbicides, which farmers could spray with abandon. After introducing genetically modified soybeans to the American market in 1996, Monsanto launched Roundup Ready beets, corn, and cotton. Now, genetically engineered varieties comprise more than 90 percent of the major crops in the U.S.

Over time, the proliferation of genetically modified crops has led to glyphosate being found in soils, water sources, air, food, and even breast milk and urine, Adams writes. At the same time, ambiguities about the implications of glyphosate’s potency and pervasiveness have been the subject of a fierce, decades-long debate about chemicals and harm.

Adams characterizes this debate as “the swirl,” a condition in which certainty is continually contested, divided, and multiplied. This uncertainty is partly a function of the way glyphosate spreads unevenly in environments and bodies: Chemicals in foods are “digestive interlopers,” she writes, clustering and potentially damaging tissues and physiological systems throughout the body.

Adams recounts the stories of several patients who came to her through her neighbor Michelle Perro’s pediatric clinic. Perro (with whom Adams wrote the 2017 book “What’s Making Our Children Sick?”) worked with children struggling with severe chronic health problems that other doctors had been unable to explain or cure. She observed that after reducing glyphosate-rich foods from their diets, children with debilitating digestive problems saw their diarrhea, bloating, and constipation disappear.

While Perro claims to have identified and tried to treat what she thinks are glyphosate’s multiple effects, some of her colleagues have called her clinical ideas speculative, and even Adams acknowledges that she could not attribute the patients’ improvements to dietary changes alone, as opposed to pharmaceutical remedies. Nonetheless, she writes, “The facts and the clinical perceptions that Michelle brings to bear on behalf of her patients reveal an attunement to and a comfort with the perpetual motion of different formations of the swirl.”

The truth is, there is no scientific consensus, according to Adams. Evidence does not just accumulate. Rather, she notes, scientists, industry, and government weave evidence together and put data and findings from disparate studies into conversation with each other.

Adams looks at large reports and reviews on glyphosate, for example, which take results and data from many independent studies to get a robust view of the evidence. She compares two studies published in 2016, one a consensus report based on hundreds of peer-reviewed publications conducted by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, the other a review drawing from 80 publications and written by a team of environmental scientists, biologists, and medical researchers in the journal Environmental Health. The consensus report concludes that genetically engineered foods and pesticides are safe for human consumption, while the review article argues that scientific evidence shows that glyphosate poses serious health risks to humans and animals.

How is it possible that the studies came to such starkly different conclusions about the health risks of glyphosate?

Adams argues that it’s not enough to simply locate where the preponderance of evidence lies. Drawing conclusions based on “data generated from a rat or mouse study here and a soil study there, an epidemiological study here and a livestock study there” is like comparing apples to oranges, she writes. By packaging evidence from different (and sometimes noncomparable) research together, she writes, these studies “erase the specific ways in which each study defines its limitations or leaves open questions of reading the evidence otherwise.”

That’s not to say the authors of the two studies misconstrued the facts. Rather, Adams highlights the inherent instability in scientific consensus around glyphosate. The uncertainty pulls readers deeper into the swirl.

Monsanto has funded agroscience departments and research institutes across the United States, and the agrochemical industry has blurred “the lines between reliable and biased science” in such a way that “makes it impossible to either discredit or believe the scientific consensus,” she concludes.

In the process, Adams draws a connection between how Monsanto — which was bought by the German pharmaceutical company Bayer in 2018 — has enlisted glyphosate in pursuit of profits and expanded agricultural outputs, and the ways activist networks have wielded the chemical to hold these actors accountable for harm, with mixed success.

The glyphosate debate with all its uncertainties “invites us to get comfortable with the movements of the swirl,” Adams writes, “from the cellular all the way to the grand social and infrastructural arrangements of capitalism, research, regulation, clinical care, and so on.”

It’s hard not to think about the current debates over masking, vaccination, and the long-term health risks of contracting Covid-19 while reading her account of scientific consensus. In fact, Adams sees the swirl as having “particular saliency in our times,” given that “the production of a scientific consensus about so many things seems to be so urgent and yet so persistently up for grabs.”

Colleen Wood is a writer and educator based in New York City. Her work has appeared in The Diplomat, Foreign Policy, New Lines Magazine, and The Washington Post, among other outlets. Find her on Twitter @colleenwood_.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Correct, Chase. It perfectly illustrates the cherry-picking strategy that is a known component of science denial. Check out the FLICC pre-bunking that climate scientists explain for more details on how that works.

Also: F = fake experts. Perro in this case. C = conspiracy theories. It’s all here.

But this whole thing is clearly an attempt to undermine consensus. When you can’t win on consensus (just like climate deniers), the next best thing is to undermine it. Cast doubt on it, in various ways.

Unfortunately the perceived “white hats” of a Moms group provides cover for nonsense. It’s true on vaccines, 5G, GMOs, and it’s a shame Undark can’t recognize this.

Thanks for your comment, Mary. I also found it puzzling that Undark would permit a citation from MAA. There’s another study that claims to have found glyphosate in breast milk, “Determination of glyphosate in breast milk of lactating women in a rural area from Paraná state, Brazil,” whose methods have been criticized (convincingly, in my opinion) by the Genetic Literacy Project. Still, a citation from a 2022 study published in a peer-reviewed journal would have been easier to understand. It’s fine for this magazine to interrogate what exactly constitutes a scientific consensus, and even to acknowledge the “swirl,” but it should also strive to be as swirl-clarifying as possible, and revise against swirl-perpetuating sources, which the MAA “study” quite obviously is.

Michelle Perro is your hero? The same Michelle Perro you can read on RFKJr’s website in the article “Dr. Michelle Perro to Fellow Pediatricians: ‘Rise Up, Take a Stance’ Against COVID Vaccines for Kids”?

And if reading is too much for you, watch the videos she does with cranks like Stephanie Seneff and Joe Mercola. Go ahead. Search “Michelle Perro Mercola”. Delightful stuff.

I actually clicked the source of the claim for glyphosate in breast milk, because I know that literature well. I cannot believe you link to Moms Across America’s bogus claims. I watched a video of theirs where they lament about how 5G is burning everyone’s skin. But you can buy their tiny hydrogen to detox glyphosate from it. Too bad you couldn’t locate the peer-reviewed literature on that subject.

I was going to ask Undark why they bafflingly lower their standards on this issue all the time. Letting anti-vaxxer funded USRTK folks write without disclosing Mercola funding, and this stunning example of dropping your credibility shields.

But I realize now that this piece is chef’s-kiss perfect: an example of how otherwise legit sites become part of the swirl of garbage on this topic.

Chef’s kiss, Undark.

Perfectly illustrated, Undark.

Chemicals in foods are “digestive interlopers,” she writes, Every one knows foods are entirely made of chemicals. Period. Since the US is almost uniquely using GM modified food and the rest of the planet isn’t it should be easy to compare statistics with the rest of the world. Science. Not selected andecdotes.