In Clashes Over Cannabis, Race, and Water, Hard Data Is Scarce

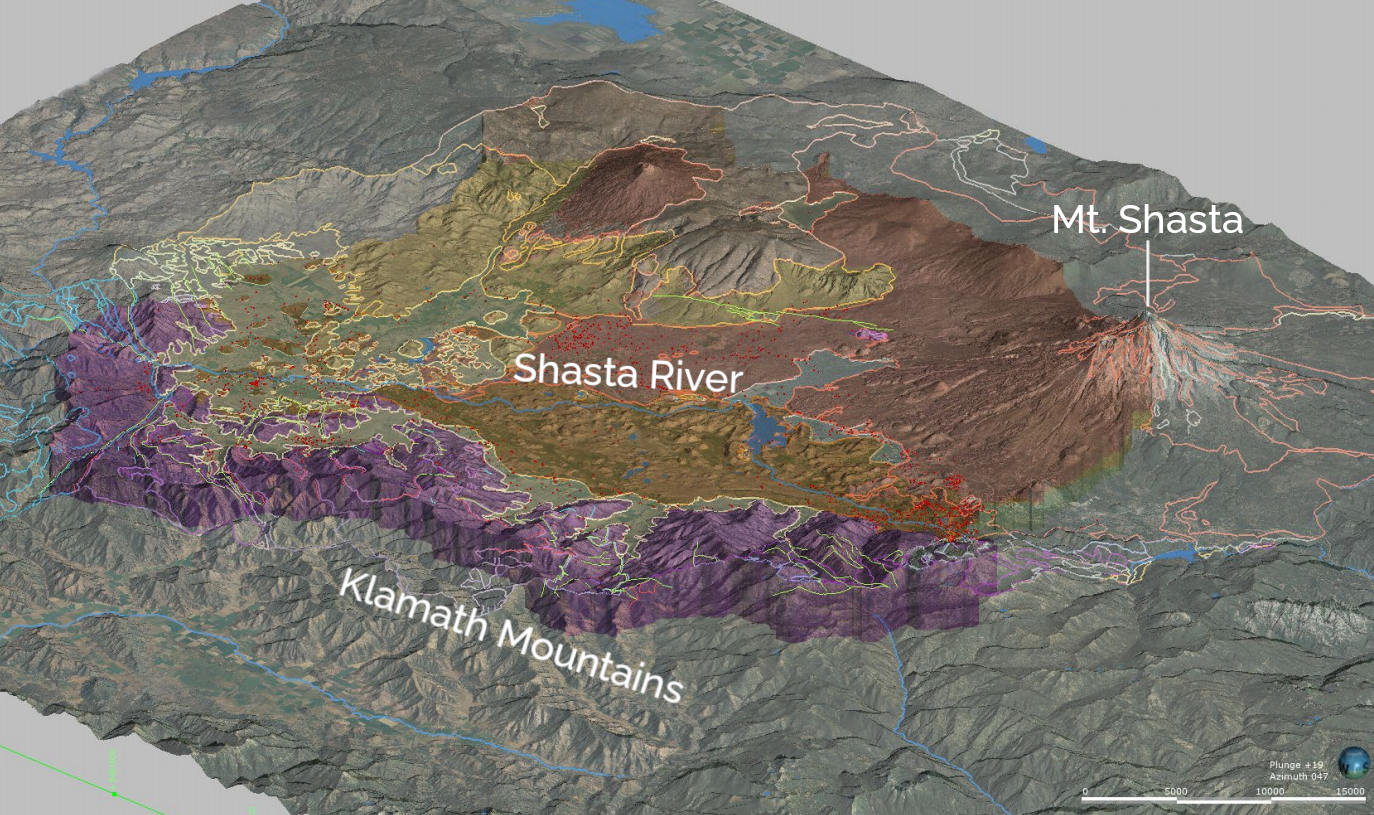

Tucked between two mountain ranges in Northern California’s Siskiyou County, the Shasta Valley is as complex as it is impressive. Brad Gooch, a hydrogeologist, is still amazed by the landscape nearly four years after first visiting the area. But it’s not because of Mount Shasta, a volcano looming 14,000 feet over forest and farmland. Rather, Gooch is confounded at how little is known about the natural resources that lie beneath the valley.

“It baffles me, to be honest,” he says.

The dearth of knowledge is perhaps most pronounced when it comes to what scientists call the hydrogeology of the groundwater basin –– how exactly water moves through the volcanic rock below the ground. The movement of that water is the economic linchpin of the valley, with cattle ranchers, alfalfa farmers, cannabis growers, and others all depending on it. And thousands of residents also depend on the groundwater for their homes.

To fill the knowledge gap, Gooch and a team of other hydrogeologists from the University of California, Davis and Larry Walker Associates, an environmental engineering and consulting firm, were hired to help fulfill the requirements of California’s landmark Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), which Governor Jerry Brown signed into law in 2014. The scientists’ task: to build a three-dimensional model of the county’s groundwater basin to help estimate changes in water levels and quality. The model would also inform the local Groundwater Sustainability Plan, which is mandated by SGMA and has to be submitted to the state’s Department of Water Resources by January 2022. “California has been the Wild West for groundwater,” says Gooch. “Drill it and pump it, it’s all yours. Go for it. That’s why SGMA was so important and long overdue.”

As it stands, the Western United States is in the throes of an era-defining megadrought, and in dry years, groundwater basins fill nearly half of California’s water needs, picking up the slack from reservoirs and other surface water sources that have fallen to historically low levels. The frequency of dry years since 1999 is “astonishing,” says University of California, Davis hydrologist Thomas Harter, who has worked in Siskiyou County for two decades. The issue isn’t going away anytime soon. As the climate warms, precipitation patterns will fundamentally change in the region, according to experts. Shasta Valley will likely see longer periods of drought and decreased snowpack in the nearby mountains.

Now, after another exceptionally dry year, more heated clashes over Shasta Valley’s water have emerged, often pitting White residents against the thousands of Hmong American families that have settled into a collection of tightly packed lots in the arid eastern region of the valley since the mid-2010s. Members of a Southeast Asian ethnic group that immigrated to the U.S. in the decades following the Vietnam War, these Hmong American families came to Siskiyou County from other parts of California and across the country. Many of the them now make a living growing cannabis in greenhouses, trucking in groundwater purchased from nearby farmers. Although California voters made the recreational use of cannabis legal in the state in 2016, Siskiyou County has banned cannabis farms and the activities that sustain them through a series of ordinances. But the cannabis greenhouses have nonetheless proliferated, both among the Hmong American community and other groups that have moved in.

Last year, the county filed two lawsuits on behalf of a group of mostly White residents whose wells had gone dry, alleging that a few farmers selling water to the cannabis growers in the subdivision are “depleting precious groundwater resources,” and jeopardizing the lawful use of water for thousands of other residents.

But advocates for the Hmong families, who now make up the majority of Mount Shasta Vista residents, say the allegations stem from a long history of racial discord and discrimination. The lawsuits’ intent, the advocates say, was not to address the rapid development of illegal cannabis, but to force the community — which includes many people who do not grow commercial cannabis, and others who don’t grow the plant at all — to leave. In May of this year, the Siskiyou County Board of Supervisors banned trucks carrying more than 100 gallons of water from certain county roads surrounding the Mount Shasta Vista subdivision — cutting off not only the greenhouses, but also many of the Hmong families who rely on the water trucks to live, raise animals, and grow vegetables on the arid land. The Hmong American community and their allies have responded with protests and boycotts. In June, lawyers representing members of the Hmong community filed a lawsuit against the county alleging discrimination based on race.

One thing missing from the roiling dispute, however, is scientific evidence that the cannabis farmers are truly running the wells dry. It’s a problem that stretches beyond the county borders, given that California has a multibillion dollar underground pot market that is currently larger than the legal one. But to understand the potential hazards of cannabis growing in the Mount Shasta Valley subdivision, the county faces a unique challenge: No one, not even the hydrogeologists, really knows how much water is being used.

Building a model of the Shasta Valley water basin is not a simple task. The unseen landscape Gooch and his colleagues study is a jigsaw puzzle of volcanic rock that makes up a third of the valley and lies directly under the region’s wells and cannabis farms. Fractures and long lava tubes run through a younger basalt layer, forming what Gooch calls a “superhighway” for groundwater.

“It’s some of the most complex geology that we have” in California, says Laura Foglia, a senior engineer at Larry Walker Associates and an adjunct professor at the University of California, Davis, who is leading the technical team advising the Shasta Valley committee. “It’s really difficult to predict the source of water and where this water is going. It’s because there are so many features in the geology that we don’t know and will never find out.”

Complicating matters, miles of impermeable hard rock jut up from below. And the valley’s rolling hills are actually remnants from 300,000 years ago, when the entire north side of Mount Shasta collapsed and spilled outwards. “It throws a huge wrench into the whole valley, you know, in a valley already full of wrenches,” says Gooch. “Basically, it’s created a whole bunch of microcosms of hydrology that makes it close to impossible to really comprehend. And, certainly, much less to model.”

Despite the complexity, the team managed to build a working model of the valley in the spring, utilizing half a century’s worth of well records from local drillers, geologic research from the mid-20th century, and surface water maps.

While the model is quite sophisticated, the data being fed into it is spotty. To produce anything other than generalizations, the researchers say, will take decades of additional monitoring.

Although the model is a work in progress, it still produces a rough estimate of the basin’s water budget and can, hypothetically, simulate various practical scenarios like drought, pollution, or groundwater depletion. A computer crunches the trove of public well-monitoring data, water flow levels from nearby rivers, and annual weather data such as rainfall. Additionally, the model uses satellite data to measure elevation changes, allowing the team to see if the ground is sinking due to groundwater depletion, and to track land use changes, like evaporation from crops and changes in soil moisture. It all runs through the three-dimensional geological map the team created.

It also comes just in time. SGMA’s deadline for the valley’s first iteration of the Groundwater Sustainability Plan is November; after review, it will go into effect next year.

The plan will likely cover a range of water uses and address a number of environmental issues, including streamflow and salmon habitat. But it is cannabis that has taken center stage in the valley. Amid the controversy over groundwater pumping, Foglia and her team are trying to maintain a just-the-facts approach while they push towards a more holistic plan. “We need good quality data to really fully nail down what the impacts are and where, because we don’t want to make it up without even having the data,” she says. “The model can help you, but the model is as good as the data that you use.”

Data points are sparse for cannabis. State officials only track a limited number of wells in the area twice a year, making variation due to whatever cause difficult to monitor, says Foglia. Any additional pumping would inevitably alter groundwater levels, but specifics on how much, and by whom, remain murky. “To fully understand the impact of the pumping, we would need at least monthly data in some of the groundwater levels,” she adds. “If we know, we know; if we don’t know, we are very open and say, we cannot 100-percent say that this is the reason.”

Illicit cannabis cultivation isn’t new to Siskiyou County. The plant has been grown in the area since at least the late 1960s, says Margiana Petersen-Rockney, a doctoral candidate in environmental policy and management at the University of California, Berkeley, who, along with a colleague, published ethnographic research on cannabis farmers in the county in 2019. “There have been White guys growing weed up in the hills for many, many decades,” she adds, “and nobody batted an eye.”

While cannabis may not be new to the area, most of the region’s agriculture — which includes farms that date back a century — had been dominated by ranching and hay production. Now, according to some estimates, there are at least twice as many cannabis cultivators as there are non-cannabis farmers and ranchers. The county sheriff’s office estimates that there are now 5,000 to 6,000 greenhouses operating in the arid eastern part of the valley alone.

For some residents, the highly visible changes challenge the area’s traditional mode of agriculture and historical ideas about farming, says Petersen-Rockney. The changes also threaten a static, nostalgic conception of rural identity, she adds, resulting in a refusal to accept cannabis farming as agriculture or its Hmong American cultivators as legitimate farmers and lawful residents. “There’s a real fear that this group, if they vote as a group, can bring political change to the county,” she says. The county’s board of supervisors and the sheriff’s office maintain that tensions over the cannabis farms relate to the legality of the crop and the environmental damage of the illegal and unregulated industry, not racial animus. But relations between local law enforcement and the Hmong community deteriorated further in June when a Hmong father of three was shot and killed by officers during the evacuation of Mount Shasta Vista caused by the Lava Fire burning in the region.

In 2016, the state of California legalized recreational cannabis, but it left it up to counties and other local authorities to write their own rules. In response to the influx of new growers, Siskiyou County passed a suite of restrictions covering unincorporated areas like Mount Shasta Vista, including a ban on growing more than a few cannabis plants outdoors and enhanced penalties and enforcement for code violations such as growing unlocked, visible cannabis. The penalties ranged from fines to seizures of property. Faced with a prohibitively expensive bar, Hmong American cultivators were in nearly “universal noncompliance” with the codes, says Petersen-Rockney, and in 2019 the county instituted a permanent ban commercial cannabis activity in unincorporated areas. The sheriff’s office was responsible for handling most of the violations, resulting in heavy law enforcement actions and crop seizures.

More recently, the county has tried to curb the cannabis farms by restricting groundwater use. In January 2020, the County passed a state of emergency declaration alleging “3 million gallons of water is being expended daily” by cannabis growers on their crops, an estimate the sheriff’s office later bumped up to 9.6 million gallons per day. Last August, officials banned groundwater extraction for watering cannabis, prohibiting the few wells that largely supply the farms from distributing water to the cannabis farms, followed a few months later by the prohibition of water trucks from certain county roads.

These more recent bans are now part of the draft of the valley’s Groundwater Sustainability Plan that was posted for public comment earlier this month. Consequently, the Hmong American community sees its water access as under threat, says Peter Thao, a community advocate who moved to the region in 2016. The groundwater, while technically nonpotable, is still used by many for daily use, such as bathing or watering animals and vegetable gardens. Some, according to a recent lawsuit, relied on it for drinking. Regarding the cannabis regulations, “they don’t want to enforce the law, but want to turn off the water,” he says. “We’re just going to be slowly dying out here because we don’t have water –– and if it’s going to cost a life out here, because somebody died because of dehydration, who is going to be accountable for that?”

In late April, despite lingering uncertainties, the technical team presented their model during a three-hour-long advisory committee meeting over Zoom. “Don’t be shocked,” Foglia joked as they prepared the presentation after a long discussion. “Maybe everybody will wake up now.” Cab Esposito, a groundwater hydrologist with Larry Walker Associates in charge of the modeling, opened a PowerPoint with images of the first public simulation of cannabis cultivation — not the greenhouses from the Mount Shasta Vista subdivision specifically, but a hypothetical scenario.

Esposito painted a bleak picture. The simulation was based on three estimates of additional groundwater pumping from a randomized set of fictional wells, which were superimposed on historical water-use data. Each scenario showed, to varying degrees, that cannabis depleted the groundwater. This seemed to justify the county’s cannabis-related restrictions and the claims in its lawsuits.

But the water-use data for the hypothetical cannabis cultivation hadn’t come from the scientists. “These are ballpark numbers that we’ve been working to develop based on information from the sheriff’s department,” Esposito said during the presentation. The numbers were based on the estimated total number of plants in the area, which the sheriff’s office claims to be two million. The goal, Esposito added, was “to try and estimate how much additional water is being used within that area.”

However, according to Ethan Brown, a geologist with the Shasta Valley Resource Conservation District, data on illegal plants are notoriously difficult to estimate –– something other experts echo. Shasta Valley has particularly sparse cannabis data and “the fact that that’s not regulated doesn’t really help,” says Brown, “because there’s just really not a good number for how many total plants.” Another uncertainty is how much water growers use per plant, since the details depend, in part, on climate, plant size, and whether the crop is grown indoors or outdoors.

Aside from contested estimates, the simulation had another problem: Scientists usually model the water used in agriculture by estimating how much evaporates from the plants and the soil — water that would eventually return to the groundwater basin. But the model scenario assumed a dramatic, and unlikely, case in which the water used for cannabis left the groundwater basin entirely. The purpose of the scientist’s simulation, they say, was to visualize, though not necessarily predict, what would happen to groundwater levels if that much water was eventually removed from the aquifer. A true-to-life estimation would require much more information. “For regular agricultural uses,” Foglia says, “we absolutely calculate how much water is returning into the groundwater through recharge. This kind of needs to be considered a special case, because we don’t know much about these applications and how it returns to the groundwater or not.”

According to the scientists, there is no consensus on the final figure. “What we have for cannabis are only estimates,” Foglia wrote in an email to Undark.

But at the meeting, some people wanted to use the partial water model to help stop the development of illegal cannabis. “The county is frustrated beyond belief at the legal process of trying to shut this down,” said Blair Hart, a rancher and Shasta Valley Groundwater Advisory Committee member. “The bureaucratic maze they have to go through to prosecute one case is unbelievable. We’ve got a mess.”

Steve Griset, an alfalfa farmer in Siskiyou County, says he sees the Hmong cannabis farmers and their families differently than how some other valley residents view them — not as criminals creating water scarcity, but a close-knit community wanting a livelihood and a place to call home. “Right in my backyard there are thousands and thousands of people that had moved in,” he says. “It really surprised me. I had never spoken to a Hmong person before I moved up here.”

Griset also saw a business opportunity and — like many of his neighbors — began selling excess water from his irrigating schedule to the growing settlement in 2016. “The way I look at it,” Griset says, “the water is going from agriculture to agriculture.”

But in the summer of 2020, the county sued Griset, pointing out that the water he was selling was going to what they considered to be an unlawful crop. The civil lawsuit alleges that he engaged in “wasteful” and “unreasonable” water use and implies that his operation may be causing other residents’ wells to run dry.

Demonstrating a direct link between groundwater depletion and cannabis is difficult, however, and the case is a good example of why focusing on science is so important, according to Gooch, who recently moved to a new position with the California Geological Survey and is no longer working on the Shasta Valley modeling. “We don’t know where these dry wells are, we only have general ideas,” he adds. “Because no one brought up information to analyze from a scientific perspective, it’s all conjecture and rumor. And unfortunately, we can’t do anything with that.”

After the county barred unpermitted transportation of groundwater on certain county roads and prohibited groundwater use for cannabis, and farmers like Griset stopped selling to water trucks, the Hmong American community was left without a main source of water and scrambling to organize against the prohibition. Community leaders have called the prohibition a human rights violation and public health crisis. Recently, the sheriff’s department has enforced the ordinance by impounding some water trucks and calling for community members with heavy machinery to help remove illegal cannabis farms.

Petersen-Rockney sees it as an age-old clash. “Water scarcity has pitted agriculture and Indigenous community livelihoods against each other for a long time,” she says. “Now, I think, a similar dynamic is happening where racialized othering is deepening conflict.”

The lack of good data on water use on the Shasta Valley cannabis farms doesn’t help. According to the technical team and an initial draft of the Groundwater Sustainability Plan, there is no immediate threat to overdrawing water from the basin, assuming there is no dramatic expansion of additional groundwater uses, which would include the cannabis greenhouses. The Groundwater Sustainability Agency plans to expand data monitoring to understand the existing growers’ groundwater use. How exactly they will do that, the technical team is not yet sure. “We have options, but we are not yet sure what will be possible when it comes to cannabis,” Foglia said in an email. “We will have to be creative to get to info that we need.”

But whether or not the water restrictions will remain in effect is uncertain, as many in the Hmong American community are demanding the immediate repeal of the ordinances. “The treatment that we are receiving here in this county will be heard in the local, state, and federal level,” Thao told a crowd of protestors in May outside the county courthouse, where Griset’s case was being heard. Earlier this month, the federal judge hearing the discrimination lawsuit filed on behalf of the Hmong community ordered the two sides into mediation to ensure that the Mount Shasta Vista subdivision had adequate water access while the court considers the broader issues.

When it comes to understanding the risk of cannabis to the basin, the expanded groundwater-monitoring network may eventually provide some clarity. But it will take time, the scientists say, pointing to the scheduled review of the management plan, which will happen every five years until 2042. “There’s really not a lot to do except make the best model we can and then hope that the people making the decisions for the future are making the best-informed decisions,” Gooch says. “Everyone wants to make the best informed decision. But it all starts with the data.”

UPDATE: A previous version of this piece incorrectly stated that Brad Gooch recently began a new position at the State Water Resources Control Board. His new job is with the California Geological Survey.

Theo Whitcomb (@theo_whitcomb) is a journalist based in Oregon. Currently an editorial intern with High Country News, he writes about natural resource politics and land-use in the the Klamath-Siskiyou region.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Wise stewardship of groundwater resources? Racism and nativism? One cannot tell without good data.