In Cape Cod, New Efforts to Coexist With Sharks

On a windy morning in March, two older surfers at LeCount Hollow Beach, on Cape Cod, look out at the gray Atlantic. They are scanning the water closest to shore for seals, with whom they increasingly have to share the frigid water, which can dip as low as 37 degrees Fahrenheit in winter. The seals are a growing demographic. They have been rebounding since the 1970s, after almost being hunted to extinction. They are recolonizing what was once their native habitat, migrating seasonally up and down the coast. The surfers, too, have started to migrate, with many now surfing exclusively in the winter — not to avoid the crowds in this popular summer tourist destination, but to avoid another growing demographic: great white sharks.

One of the surfers, Charles Cole, who goes by Ch’arlie or Ch, has a long flowing beard bleached a light yellow from years of sea and sun. He has been surfing here off the coast of Massachusetts since the 1960s. “There used to be one or two sharks every summer,” he says. Now there are too many to even count. Cole has painted the bottom of his kneeboard with alternating stripes of white, black, and gray — a signal to let the sharks know he isn’t a seal. But just in case, his surf leash attached to the back of the board has a mechanical ratcheting buckle for tightening. “I bought one of these because it’s a tourniquet,” says Cole. Devices like this are usually used to stop heavy bleeding after traumatic injuries from gunfire, road accidents — and shark bites.

Even with these precautionary measures in place, Cole says he won’t go out if the water appears too “sharky” — a sixth sense he has developed to tell him if sharks are present. And from about July to October, during peak shark season for what has now become one of the greatest concentrations of great white sharks in the world, the waters are very, very sharky.

For ecologists, the return of the sharks is hailed as a cascading conservation success story. Protection of Cape Cod’s unique seashore and the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act are credited with the return of the region’s gray seals — a preferred food source for great white sharks. The seals’ main stomping ground is the eastern shoreline of the Outer Cape, which extends like a forearm from the peninsula’s southern elbow to its northern fist. Here, 3,000 miles of open ocean, wind, and waves ram into the land, forming dramatic dunes that can reach 100 feet and attract millions of visitors every year. As the seal population has grown, so has the number of sharks and shark interactions, causing the Outer Cape’s four small towns and the National Park Service to grapple with competing demands of conservation and public safety.

Many societies have coexisted with large apex predators for centuries, but Western countries have tended to favor either eradication or separation. In Western Europe, for example, bears and gray wolves were largely exterminated by the late 19th century, and even though wolves have successfully returned, countries such as France, Norway, and Finland still routinely cull them. Separation looks a little different: In the United States, grizzly bears are largely tolerated within designated wildlife reserves and national parks, but if they go outside those boundaries, they risk being relocated or euthanized.

As one of the ocean’s top apex predators, great whites have been the target of intense management plans. Countries around the world have spent millions of dollars to install nets, barriers, and bait-lines to keep sharks away from humans, with mixed success. But now, increasingly sophisticated satellite and tracking technology might offer new, more detailed insight into how sharks behave. Among other things, researchers are creating a tool to predict the presence of sharks in the water. “Like a weather forecasting system just for sharks,” says Greg Skomal, a senior scientist at the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and a leading shark researcher.

That tool is what’s known as a heat map — a color-coded graphical representation of data. In this case, the goal is to map shark swimming behaviors and their relationship to environmental conditions, like water temperature, tides, and even lunar cycles. Researchers hope this heat map will give beachgoers and public safety officials the ability to predict the likelihood of a shark swimming near the shore. It’s not just a novel experiment for understanding shark behavior. Some researchers see it as emblematic of a growing shift in conservation science, as well as in Western societies, to finding more equitable ways of living with wild animals. In Cape Cod, being able to predict the presence of sharks in the water could allow beachgoers to coexist with the 2.5-ton animals whose ancestors have dominated the ocean for 450 million years.

Sharks were once abundant in the Northwest Atlantic. Almost 200 years ago, Henry David Thoreau took a series of trips from his home, about 20 miles west of Boston, to the windswept landscapes of Cape Cod. In his book about the region, he observed that no one swam on the eastern side “on account of the undertow and the rumor of sharks.” Thoreau recounts a local’s story of using oxen to drag a 14-foot “regular man-eating shark” he had killed out of the ocean. The author even spots a possible shark swimming not far from shore.

Published in 1865, the book, titled “Cape Cod,” gives a glimpse of the region before governments in New England wiped out the seal population by offering a bounty on seal noses, after inaccurately blaming them for declining fish stocks. As many as 135,000 seals were killed between 1888 to 1962, according to some estimates. By the time the Marine Mammal Protection Act was enacted in 1972, seals had been all but exterminated. Since then, though, the seals have returned in the tens of thousands to Cape Cod, a small slice of the roughly 450,000 gray seals that now live in the Northwest Atlantic.

Sharks, too, were nearly wiped out. The loss of their primary food source combined with a deadly mixture of trophy hunting, culling, and industrial fishing led to the near extirpation of coastal shark species. And as coastal development ramped up across the country and human-shark interactions increased, so did the perception that sharks were dangerous to humans. This spurred an increase in programs aimed at managing human-shark conflicts, often through lethal means. For example, the state government of Hawaii spent more than $300,000 on shark control programs between 1959 and 1976, killing almost 5,000 sharks in the process.

In the Northwest Atlantic, shark populations hit a dizzying low. By 2003, a few years after fishing for great whites was officially banned, their population had declined by as much as 75 percent in the previous 15 years. The species has since rebounded; Cape Cod has become the world’s newest hotspot, with great white sharks steadily returning since at least 2009, when the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries began to consistently tag them. “A lot of people recognize it as a conservation success story,” says Megan Winton, a research scientist at the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, an organization dedicated to research, public safety, and conservation of great white sharks. “But now the community is really trying to figure out how to coexist, as people who like to use the water.”

Heather Doyle looks out at the ocean from the Newcomb Hollow Beach parking lot, which is covered in sand from a late winter storm. A few miles to the south, in 2017, her friend’s paddleboard was bitten by a shark just 90 feet from shore. “That was a big eye opener for everybody,” says Doyle. The following year, a few miles to the north of Newcomb Hollow Beach, a doctor was bit in the torso and leg. He survived; but then a month later, another shark fatally wounded college student Arthur Medici. Doyle points down the shore: a small, inconspicuous cross commemorating Medici teeters at the edge of a dune.

Medici’s death was the first shark fatality in Massachusetts since 1936. “We’re on a trajectory, right?” says Doyle. “It was three bites in 14 months.” After her friend’s paddleboard scare, Doyle co-founded Cape Cod Ocean Community, a community group that eventually became a nonprofit dedicated to increasing public safety. The group has helped connect pilots with lifeguards to alert them to possible sharks. It has raised funds for drones and giant car-sized balloons with high-definition cameras that could spot sharks, and it has advocated for devices such as the Clever Buoy, a marine monitoring and alert system that detects large marine life in the water.

But a six-month study commissioned by the Outer Cape towns and released in October 2019 looked at the efficacy of more than two dozen shark mitigation strategies, including the Clever Buoy, as well as nets, virtual barriers, electromagnet devices to deter sharks, and drones, among others. The report ultimately concluded that most either didn’t have enough evidence they actually worked, had limited efficacy, or wouldn’t work on Cape Cod’s shoreline — except one: modifying human behavior.

This has been the primary way that public safety officials have mitigated shark risk over the past eight to nine years, said Suzanne Grout Thomas, director of community services for Wellfleet, a fishing town about 15 miles from the tip of Cape Cod. Since Medici’s death, towns have stepped up their protocols, limiting how far out people can swim and closing beaches to swimming sometimes several times a day. Lifeguards and even some members of the public are trained in “stop the bleed” practices for bites, while signs warn about the presence of sharks. “Our biggest contribution to this is educating the general public as to how sharks can be anticipated to behave,” says Thomas. And she already sees signs it is working. People swim closer to shore, or don’t swim at all, and they react faster when the lifeguards blow their whistles to clear the water.

Last summer, Wellfleet had two buoys that sent a signal to lifeguards. If a tagged shark came within 200 yards, they could call swimmers out of the water. “There were hundreds and hundreds of sharks that pinged those buoys last summer,” says Thomas. Her goal is to have one at every beach.

But this approach, she acknowledges, has its limitations. Not every great white shark is tagged, and cellphone network service at the Outer Cape beaches is still spotty at best, meaning any live notification systems are difficult to share widely.

As researchers and residents consider the best mitigation strategies, one strategy — culling — has stayed off the table. That’s an approach some countries have tried. Western Australia, for example, implemented a regional policy in 2012 to track, catch, and destroy sharks that have posed an “imminent threat” to beachgoers. But according to the International Shark Attack File, a global database, shark attacks in Western Australia have been on a downward trend, but in the past couple years have spiked again. While estimating the effects is difficult, many experts still say culling projects don’t work.

Now, technological advances and a growing understanding of animal intelligence are giving researchers hope that another management option may be on the table, one that seeks to understand, rather than modify, shark behavior.

The ocean floor of the Cape is an immense patchwork of sandbars, shoals, and deep trenches. Sharks have learned how to navigate this underwater labyrinth. They now hunt in what some call “the trough,” a deep area of water that forms like the letter C between the outer sandbar and the beach. Because seals are often found in these shallow waters close to the shore, the sharks have learned how to attack laterally, rather than ambush from below. In fact, unlike in other areas of the world, sharks on Cape Cod spend around half of their time in water shallower than 15 feet, according to a recent study that analyzed data collected about eight great whites.

“It was really powerful for us to be able to come up with a number to tell people,” says Winton, the shark researcher who co-authored the study along with Skomal. “It really helps increase awareness of these animals and their presence.”

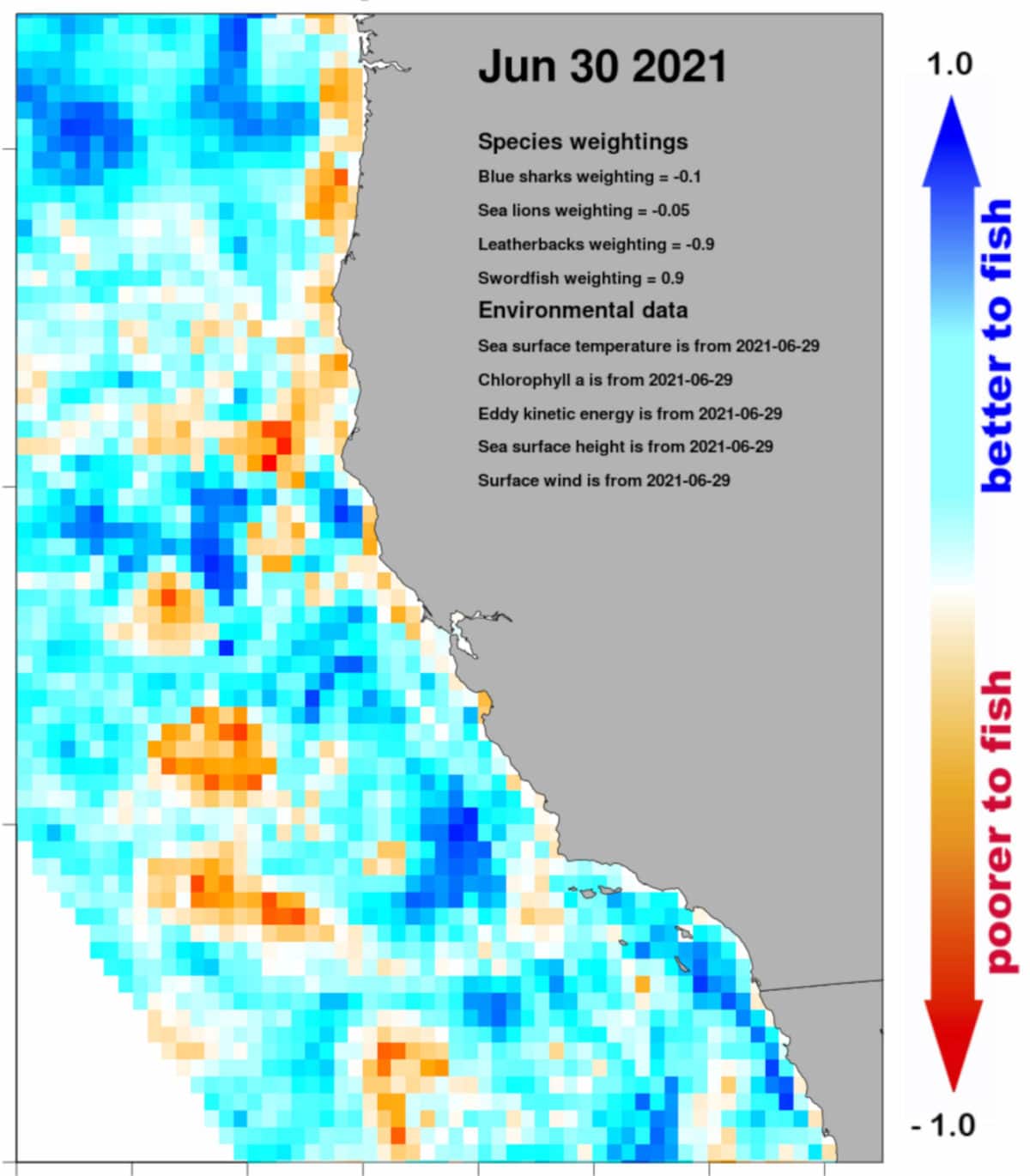

Winton and her colleagues hope to take this data point and layer it onto other data points about shark behavior and environmental conditions. The goal is to create a dynamic heat map akin to a weather forecast that can indicate the probability of a great white shark in the water, similar to maps used by commercial fishermen to indicate fish abundance. This, in turn, would help beach managers and would-be swimmers assess the risk of going in the water.

This fishing heat map, called EcoCast, tracks fish abundance off of the coast of California. Similar maps are in the works to forecast “sharky” waters.

Visual: EcoCast / NOAA

To estimate the great white shark population, Winton has already spent years following the sharks around Cape Cod in a boat, getting close enough to take videos of their unique scars and other identifiers with a GoPro stuck to the end of a painter’s pole. She and her research team have sifted through more than 3,000 videos and identified more than 400 individual sharks, often by their unique scars or fins, along with another possible 104 that require additional documentation to confirm.

She has also collaborated with colleagues and organizations that collect data from other kinds of devices: Acoustic telemetry, pop-up-satellite tags, smart position and temperature (SPOT) transmitting tags, and underwater drones. Each device gives scientists a unique data set. Acoustic tags, for example, emit a high frequency sound that is picked up by hundreds of receivers in Massachusetts coastal waters. Researchers can then use these to study where great white sharks spend their time, when they arrive, and when they leave. The researchers can track individuals in the water, as well as where the sharks travel from year to year. And as the scientists collect more data, they can figure out not only which sharks are doing what, but also whether their behavior is changing over time. The long-term goal is to use all these devices to produce heat maps on an automated daily basis for towns and public safety officials. A hotter color around a specific beach or area would signify a higher likelihood of running into a great white.

As far as Winton knows, she and her colleagues are the first to develop this type of map of sharks’ behavior, and she hopes it will be a useful tool for public safety. “This is a way to provide science-based information to people alerting them to when sharks are likely to be present,” she says.

Or as Cole might say, the map is just a scientific way to assess whether the ocean is “sharky” or not.

For now, residents and officials on Cape Cod interviewed for this article seem intent on figuring out ways to coexist with, rather than manage, the sharks — though not all of them used the term “coexistence.” That term has only recently gained prominence among Western academics and conservationists. At its core, coexistence describes a state in which humans and wildlife share the same landscape. And while that may sound Pollyanna-ish, scholars and policymakers don’t frame it as such. “Coexistence doesn’t require you to love your neighbor, or your enemy, or that marauding beast,” says Simon Pooley, a researcher at the University of London. “It requires you to figure out a way of existing in the same space and getting what you need.”

Pooley and other researchers maintain that promoting coexistence will be important for sustaining wild animal populations into the future. “Many of the places where these dangerous animals persist — they persist because there is coexistence in those places,” he says. This is especially apparent in Indigenous-managed lands that contain about 80 percent of global biodiversity, including vital habitats for predators like jaguars, polar bears, and lions. He himself studies communities in Western India that coexist with wild crocodile populations. And in India’s Sunderbans, a region of marshy land and mangrove forests populated by both humans and tigers, provides the largest remaining Bengal tiger habitat in the world.

Whether Cape Cod will become a model for coexistence is an open question. Currently there are no plans to put up barriers, or to bait and cull sharks, although a more heated debate has erupted around whether and how to deal with the tens of thousands of seals that have recolonized the Cape. Winton, who hopes to have beta versions of the predictive maps ready by the end of this year, is excited about the immense amount of data still out there that could be used to better understand sharks and their behavior.

“The more we learn about these animals, the more we just realize we’ve only started to scrape the surface understanding them,” she says. “I am just so excited for what the future holds — for not just shark science, for all of wildlife science.”

UPDATE: An earlier version of this article incorrectly described India’s Sunderbans region as being “further south” of coastal communities in Western India where crocodile populations are common. The Sunderbans are roughly 1,000 miles east of this location, on the Bay of Bengal.

Sarah Sax is an environmental journalist based out of Brooklyn who writes about the intersection of people, nature, and society. You can find her on Twitter @sarahl_sax.