Upon learning that the paleomammalogist Ross D. E. MacPhee spends much of his time at field sites in Siberia and the Yukon, people often ask him if he has ever found a mammoth mummy. He confirms that he has and then braces for the inevitable follow-up question: “Did you eat it?”

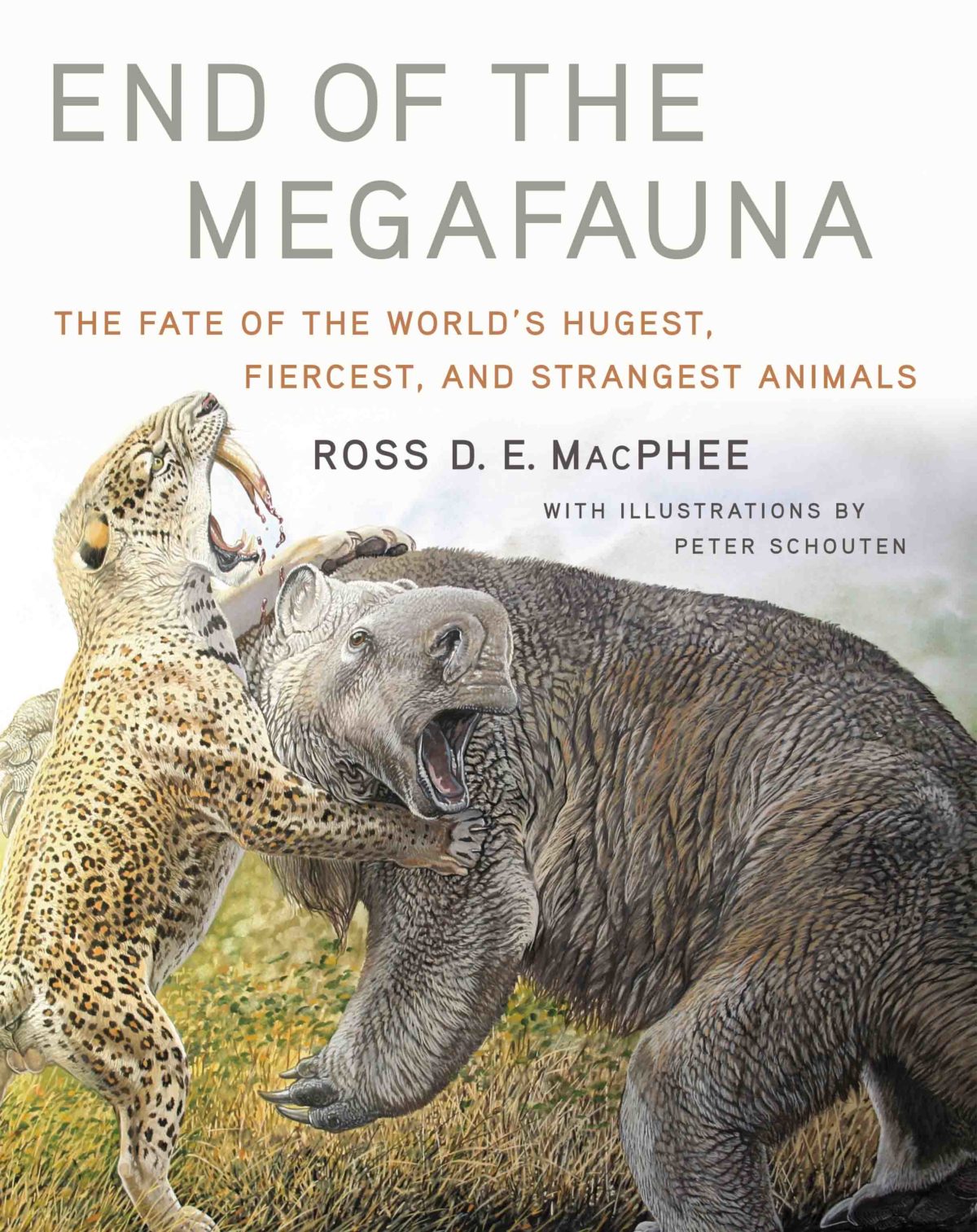

BOOK REVIEW — “End of the Megafauna: The Fate of the World’s Hugest, Fiercest, and Strangest Animals” by Ross D.E. MacPhee (W. W. Norton & Company, 256 pages).

In his new book, “End of the Megafauna: The Fate of the World’s Hugest, Fiercest, and Strangest Animals,” MacPhee sets the record straight: No, he has never eaten any of the mammoths he’s unearthed. Doing so, he points out, would be like sampling “that road pizza of a deer you saw on the side of the interstate last week,” and indeed, some of the tusked skulls he has examined have been “literally bursting with larval stages of Pleistocene flies and beetles.”

But the real meat of MacPhee’s book is not recounting his adventures during the 50-plus global expeditions he has led as a scientist with the American Museum of Natural History, but the debate at the heart of his field. Namely, what caused the relatively recent extinction of nearly every large terrestrial vertebrate on the planet, from South America’s 4,400-pound giant ground sloth to North America’s 2,000-pound short-faced bear?

Fifty-thousand years ago, giant owls, lemurs, elk, horses, armadillos, marsupials, cats, snakes, tortoises and many other behemoths roamed every continent but Antarctica. But then, in a blink of evolutionary time, virtually all but elephants, rhinos, and hippos disappeared. It is “the greatest of all extinction puzzles,” MacPhee writes, and teasing this mystery apart is the central theme of his book, which is gorgeously brought to life by the illustrator Peter Schouten.

Two schools of thought have emerged to explain these losses. The first is based on climate change — of “nature turning on itself, impassively destroying life like some careless child breaking its toys, then moving on, oblivious,” MacPhee writes. The second points to human persecution, in which we fill the role of the careless child, “killing indiscriminately in the timeless garden of nature.”

The climate argument first emerged as the leading contender, but it falls short when applied across continents. As MacPhee points out, if global climate change forced the extinction of Australia’s megafauna 40,000 years ago, then why did Africa’s largely escape unscathed? Or why was there a 30,000-year gap between Australia’s megafauna extinctions and those in the New World? How come it was generally only the biggest of the big that went extinct — and why wouldn’t mammoths and moas have just walked a bit south or north as their choice habitats shifted with changing temperatures?

The human-caused extinction argument received a critical boost in the 1960s, when Paul Martin (1928-2010), a paleoecologist at the University of Arizona, applied radiocarbon dating to test that hypothesis. Following the arrival of humans, Martin found that islands lost their largest-bodied biodiversity within decades or centuries, while continents became giant-free within a millennium at most.

Martin devised an ecology-based explanation known as the overkill hypothesis. Typically, predators and prey engage in “the oldest interactive game on Earth,” MacPhee writes, a relationship “as intimate as a love affair.” Hunters and the hunted are finely tuned to each other, and their populations exist in a dynamic equilibrium that ensures mutual survival. Herbivores would eat themselves into starvation were it not for predators picking off the weaklings, and predators would equally starve if they suddenly gained an upper hand on every antelope, mouse, or bunny in their environment. Individuals might not win, but their populations do.

As humans fanned out across the Earth, however, Martin believed they stepped outside of nature’s delicate system of checks and balances. He imagined these savvy, newly arrived bipedal predators as carrying out a “blitzkrieg” on the naïve, hapless megafauna around them — an “intentionally haunting metaphor that suggests a relentless, almost fanatical devotion to annihilation,” MacPhee writes. Native fauna simply did not have the time to develop life-saving adaptive responses to this “culture-bearing, unimaginably dangerous” alien foe.

Martin’s break from climate change and his strong focus on human-caused loss of megafauna marked “a radical departure from orthodoxy,” as MacPhee writes, and at first, it seemed to hold up. Computer models supported his findings and increasingly sophisticated radiocarbon evidence did not refute them.

But as the years passed, holes in the theory began to emerge. For example, scientists now believe that humans arrived in North and South America much earlier than originally thought, meaning our species would have co-existed with megafauna well before the extinctions began. Other researchers found that Australia’s giant species seem to have been primarily forced out by increasing aridification rather than hunting (some researchers, however, believe that humans caused that aridification by setting fire to forests). And while some scientists remain committed to the climate change hypothesis, others argue that disease or a six-mile-wide comet striking the Earth are to blame.

MacPhee wades into the weeds of these and other scientific arguments, sometimes too deeply for the casual reader, and the lack of payoff at the end is a bit frustrating. We still have no definitive answer to what caused the megafauna to disappear, and quite possibly, we never will. But that’s where the science now stands.

Most likely, MacPhee offers, many near-time extinctions were caused by a perfect storm of cofactors, some of which we may not even be aware of yet. It’s also worth noting that ecologists and conservation biologists — those at the forefront of the current human-driven extinction crisis — tend to side with Martin. If people, for all our supposed enlightenment, continue to overexploit and damage our planet and the fellow creatures occupying it today, why wouldn’t we have done exactly the same tens of thousands of years ago? In short, MacPhee writes, these scientists “know what they see.”

Rachel Love Nuwer is an award-winning freelance science journalist whose writing has appeared in The New York Times, National Geographic, Scientific American, BBC Future, and elsewhere. She is the author of “Poached: Inside the Dark World of Wildlife Trafficking.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

A very small part of African megafauna is still with us. We are in the process of wiping it out in the timescale of a few decades (we would have already wiped out the African elephant if a move to preservation hadn’t gone in the other direction, and created reserve area specifically to save them. And that effort is currently in complete failure to save rhinos which are going extinct at an accelerated space. The elephant itself is again endangered and nothing garanties it won’t end up badly within the next 50 years).

Meanwhile the hunters with spears lived with that disappeared fauna for thousand of years. It’s disparition seems overnight only a geological scale, comparatively what we are doing currently with so many species is so fast it would be like a Thanos snap.

African megafauna still with us after another many more millenia , and human numbers at colossal levels in comparision to then, and a continent pillaged for resources on massive scale. And, look at the conflict/weaponry/hunting with rifles etc that’s raged there. Yet we are supposed to believe a tiny human population wiped these animals out virtually overnight with spears? Peoples, incidentally who by most known similar contemporary cultures hunt sustainably. And Inuit for eg still have megafauna like polar bear and musk ox. So how likely is Overkill? Its not hunters that wipe out animal populations – every wilderness with apex predators for eg is stewarded by a hunting culture.

His numbers and comeback should receive national

recognition. We meet people who have reached rock band. If

this occurs, clean up your quill or mouse and run for the hills!

Night Ministry in the creation would be a Christian Ministry.

I would loke to think future generations will be grateful for saving biodiversity and the environment- at least future generations of animals. But it occurs to me that they won’t know what they’ve lost. Each generation knows little about what used to be. Still what we are doing is not worthy of our better nature.

Horses, a big animal, survived in Asia where they were domesticated.

Horses went in extinct in North America where they weren’t.

Humans had the power to extinguish all horse lines, but didn’t.

Because we found a use for them. (other, than as prey).