I’d had intestinal distress before, but never like this. I was excreting not just waste, but blood and bits of my colon’s lining — up to 30 times per day. My abdominal pain hit deeper and felt less productive than the pain of giving birth, epidural-free, to my second child. Even shingles, which stung like a dental drill against my face, paled in comparison. Such was the agony of Clostridium difficile.

VIEWPOINTS

Partner content, op-eds, and Undark editorials.

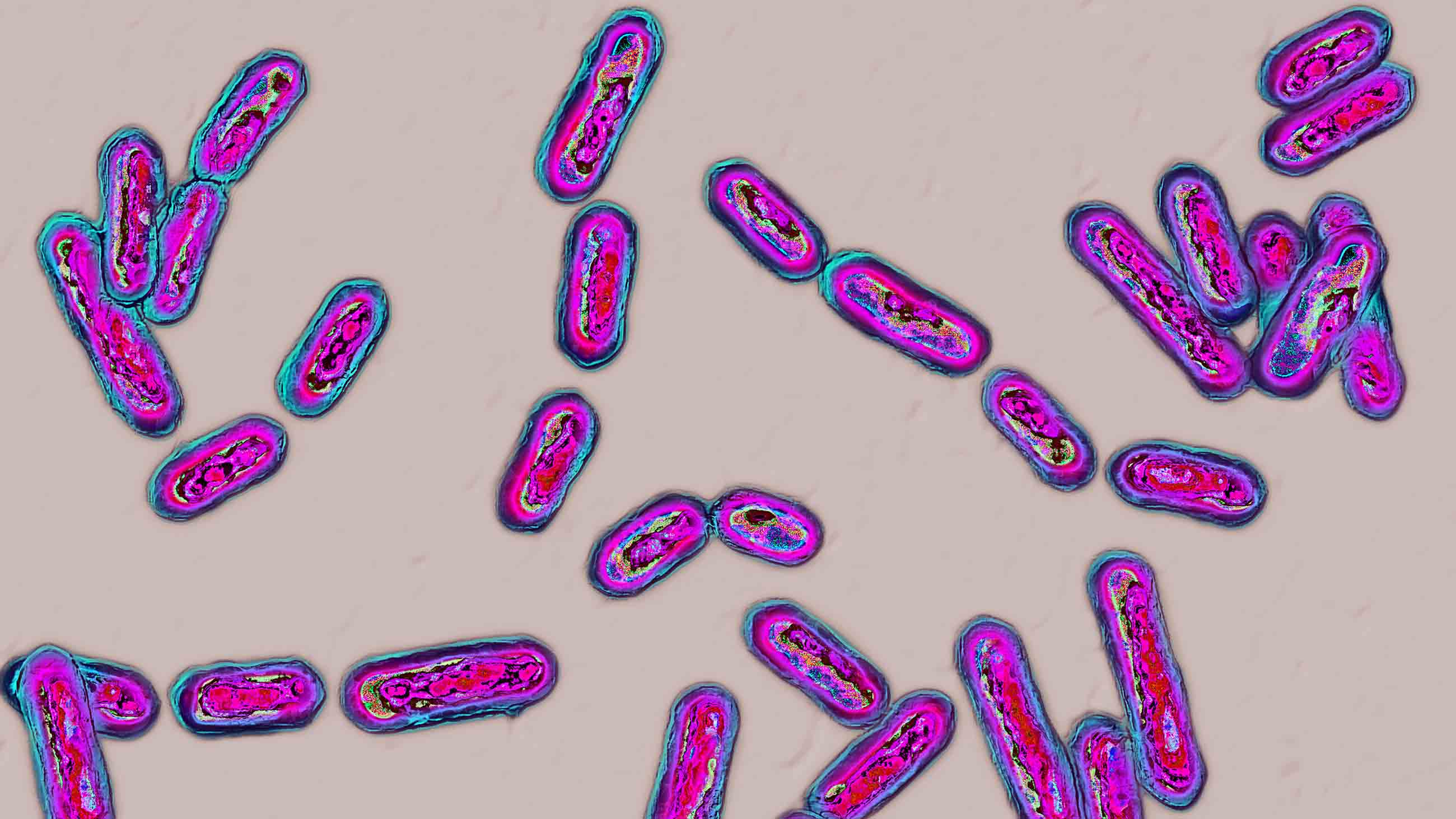

Commonly known as C. diff., Clostridium difficile is an antibiotic-resistant superbug carried by approximately 5 percent of the adult population. The harmful gut bacterium is normally kept in check by other, good bacteria in the gut’s microbiome. But when the microbial balance is upset — for example, by a dose of antibiotics — C. diff. can gain a foothold. Left to multiply unchecked, it may kill its human host.

In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that 14,000 Americans die each year from C. diff. Thanks to an ill-considered decision by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and the willful ignorance of a string of doctors charged with my care, I was nearly one of them.

Things started innocently enough. In early 2013, my doctor diagnosed me with a bacterial infection and prescribed an antibiotic. I had lived antibiotic-free for nearly four decades — a streak I was not inclined to break. But my doctor insisted on antibiotics, and I reluctantly complied.

Soon after, my stomach turned against me. I went to an emergency room and was sent home with a prescription for vancomycin, an antibiotic reserved for serious bacterial infections. But the drug proved little match for the microbes that had bum-rushed my colon. My weight and fluid loss accelerated. My colon risked perforation.

Because C. diff. spores can live for months on bedrails, doorknobs, and linens and easily shrug off common detergents and sanitizers, my master bathroom became my biohazard containment unit. There, I alternated between sitting on the toilet and lying on the floor. My husband, Esteban, brought me supplies and emotional support. My two children, 9 and 11, had been instructed to stay away. I missed them.

Desperate, I looked for C. diff. cures and treatments on my phone. That’s when I learned about fecal microbial transplants, in which stool from a healthy donor is infused into the gut of a sick patient, to restore microbial balance.

Although the procedure has only recently gained popularity in the U.S., it’s been around for ages. Academics at Nanjing Medical University in China and the University of Maryland School of Medicine noted in 2012 that fecal transplants were performed in 4th century China, during the Jin dynasty. The authors wrote that the first Chinese emergency medicine book, “Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang” (or, “Handy Therapy for Emergencies”) stated that patients dying from severe diarrhea could be cured with a swallow of a human feces suspension.

Not until 1958 did the procedure appear in modern scientific literature, in the journal Surgery. Over the decades that followed, the ancient remedy repeatedly demonstrated its mettle. In 2012, Larry Brandt of New York City’s Montefiore Medical Center wrote that fecal transplantation “has been shown in numerous case series to be a rapidly acting… safe… and highly effective… therapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection.” Nine times out of 10, he found, the stool infusions vanquished even the most stubborn C. diff. infections — sometimes in a matter of hours. One research trial comparing the efficacies of fecal transplantation and vancomycin in patients with recurring C. diff. had to be stopped for ethical reasons, when it became clear that participants assigned to the fecal transplant group were recovering while those in the vancomycin group worsened.

As I learned all this from my bathroom quarantine, I was unaware that the FDA was then moving forward with a ruling that would make it nearly impossible for people like me to access the scatological remedy: The agency had decided to classify human stool as an “investigational new drug,” which would effectively bring fecal transplantation to a halt in the U.S.

The FDA’s rationale was thin, at best. As Brown University and MIT researchers argued in a Nature commentary, conventional drugs “are produced under controlled conditions with consistent, known ingredients. Stool is a variable, complex mixture of microbes, metabolites and human cells. It cannot be characterized to the rigorous standards applied to conventional drugs.”

Nevertheless, a handful of doctors navigated the new regulatory hurdle and continued to perform fecal transplants in clinical trials. So, when I called around about the possibility of treating my C. diff. with a fecal microbial transplant, a sensible doctor might have offered to refer me to one of those approved practitioners. Instead, everyone I talked to refused to even entertain the idea, seemingly out of disgust.

“Yuck, you don’t want that. Just stay on the vancomycin,” my first doctor told me. A second, a gastroenterologist, simply substituted “gross” for “yuck.” A third, more tactful, expressed relief that FDA policy absolved him from having to offer the procedure.

As it turns out, such responses weren’t out of the ordinary. “There is a clear discordance between physician beliefs about [fecal transplants] and patient willingness to accept [fecal transplants] as a treatment,” wrote a team of U.S. and Canadian physicians, after surveying more than 100 physicians about their attitudes toward the procedure. On average, physician respondents rated all aspects of the procedure to be “at least somewhat unappealing,” whereas patients had demonstrated a clear willingness to accept the C. diff. treatment.

Gastroenterologist Ciarán Kelly mused in a 2013 editorial that the unappealing aesthetics of fecal microbial transplantation might be one of the main reasons it hadn’t become routine therapy for C. diff. infections. In 2012, Brandt wrote that prospective transplant recipients were being discouraged by the “intransient negativism” of physicians, who described the procedure as “quackery,” “a joke,” and “snake oil” — despite its track record in case series.

And so it happened that when my C. diff. roared back, worse than before, after the end of my 10-day vancomycin course, my doctor’s response was to simply prescribe more vancomycin. With each subsequent treatment, however, my likelihood of recovery dropped dramatically. I started the ordeal with an approximately 70 percent chance of recovery. After months of failed antibiotic treatments, my chances had sunk below 10 percent.

My last trip to the emergency room was a grim formality. The C. diff. battle now raged beyond my colon. “You may want to tell loved ones about your dire circumstances,” my gastroenterologist said. It dawned on me that my doctor would sooner let me die than discuss a fecal transplant. That’s when I decided to do the transplant myself.

This was in the dark ages of fecal microbial transplantation, before the procedure became ingrained in the American psyche. But there were a handful of websites that offered advice on do-it-yourself fecal transplants. Some were more questionable than others. One dubiously suggested using pet feces for the donor sample.

But even with an appropriate two-legged donor, the procedure would carry risks of infections and the possibility of other adverse outcomes. My friends cautioned me against “going rogue” with an “extreme,” “unapproved” treatment. But to me, the gamble was worth taking.

A New England Journal of Medicine article offered some procedural clues. For instance, my ideal donor would have a microbiome that was untainted by antibiotics. That ruled out Esteban, who had recently been administered antibiotics during an eye surgery. Ultimately, I turned to my 11-year-old daughter.

She responded openly and inquisitively, asking more questions than any of my doctors had. “Is this like in Clash of Clans when you have no troops left in your clan castle and you need someone else to donate some?” she said, referring to a popular multi-player video game.

Yes, it’s exactly like that.

She agreed to do it, and at around 10 pm on a Tuesday, Esteban collected the sample. He dropped it into a blender, added saline, blended it, strained it, and poured the concoction into an enema bottle, as I lay depleted on the floor. My gut drank up the infusion as if it were dying of thirst. My colon, after five months of near-constant spasms, recovered in one transformative instant. Overnight, I went from having 30 bowel movements a day to having one. For breakfast the next morning, I ate a quesadilla loaded with black beans, cheese, salsa, lettuce, and guacamole. I’ve had no recurrence of C. diff. since.

Within a month of my five-month ordeal, the FDA announced a “compassionate use” exception to the restriction on fecal transplants, which gave physicians more freedom to offer the procedure to C. diff. patients. Within a year, MIT opened the first public stool bank, and the Cleveland Clinic named fecal transplantation a “Medical Innovation of 2014.” Today, the stigma around fecal transplants has mostly worn off. A recent doctor, upon hearing my story, joked with a colleague that I’d had a fecal transplant “before they were cool.”

I am glad that patients now have wider access to this life-saving treatment. Still, I remain wary of doctors and policymakers who once withheld that access from me and thousands of others like me. Their irrational aversion to feces — the biological agent that we all produce —nearly killed me.

Susan D’Agostino is in the MA in Science Writing program at Johns Hopkins University and is a Taylor/Blakeslee fellow of the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Chuck Gosh, I’m sure you mean well, but I don’t think it’s reasonable to suggest a conspiracy on the part of the medical community. I don’t doubt that there are some greedy individuals from CEO’s to doctors who prefer the status quo, but most of the individuals in the medical community are ethical.

Research and testing is still being conducted, the use of FMT has been increasing, the US has a public stool bank, while Europe has multiple banks. Moreover, there is also research on cultured bacteria as a standardized, safer and more effective approach to FMT.

Progress is often frustratingly slow, even for promising treatments, but there doesn’t seem to be any serious conspiracy at play.

My father had a fecal transplant in October 2017 at a hospital in the SF Bay Area after several hospital visits for C. diff. During the hospitalization in which he received the transplant he had started bleeding from the colon as described in Susan’s article, which at age 86 posed a whole other set of trade-offs and considerations. The transplant procedure was explained as still under FDA investigation but that my father’s circumstances indicated he was a good candidate. Generally the medical staff, and infectious disease specialists in particular, spoke quite hopefully and positively about the procedure, although of course they could not speak to my father’s chances of recovery. (However, the palliative care team was vocally skeptical without much basis, which appalled me.)

After a month in the hospital, including one week in ICU, my father pulled through. He is now back to golfing and making supervised visits the gym on a regular schedule (!).

Susan, Great debut article in Undark! Your story was incredible when I first heard it. Raising awareness about C. Diff and all it’s adverse effects on health is very important. Overuse of antibiotics is a knee jerk reaction that is deeply entrenched in American medicine but happily the tide is slowly turning on that. With the proper support our immune systems are designed to fight many infections. It is now very apparent that inappropriate use of antmicrobials has resulted in the propagation of very resistant microbes. Fecal transplant is a perfect example of supporting the immune system with a healthy outcome and you are living proof!

Wow! I had no idea so many people would respond to my “rant.” Here are some additional resources (and more rant):

Taymount Clinic videos:

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=taymount+clinic

Probiotics are better than nothing. But most probiotics sold in capsules are actually just milk microbes. Read the label. Why not just go right to the source? All that other stuff in there makes the whole package work better.

Raw Milk Finder:

https://www.realmilk.com/real-milk-finder/

Raw milk is sold in grocery stores in many states, delivered only to members of a “club” (cow-share contracts permit delivery of your milk from your leased cow, they don’t “sell” milk) in other states, and thoroughly illegal in Kentucky and Louisiana. It’s not cheap, it’s not easy to find in many areas, but it’s something that my wife and her good friend cannot do without. The days of them hopelessly doubled-over in pain in bed for three days straight are gone. Polished off her rosacea, too (another auto-immune disorder). Bonus.

Lol, when anyone asks where I get the milk, I tell them I get it off the back of a truck in a church parking lot. All true.

What my wife and her friend (and so many other people) were experiencing was an allergic reaction. A rash in the lining of their small intestine (or on the face for rosacea).

We plan vacations and trips around bringing raw milk with us in the car, staying in motels with a refrigerator (or putting it in the motel’s food refrigerator) and a cooler with cold packs or ice or finding it near our destination. It keeps for 2 weeks as long as you keep it cold. Easiest places to find it in stores for us are CA, OR, WA, FL.

If you must, consider taking an oral antihistamine at the first signs of distress to calm your immune response. This is a band-aid approach but is better than suffering. This basically “dumbs down” your immune system. Not a good idea long-term, but it’s exactly what most new expensive miracle drugs do. That’s why they have so many warnings about infection, foreign travel, tuberculosis, fungus, etc.

Don’t tell your friends and family you’re drinking raw milk. They’ll tell you that you’re crazy. Share with other sufferers. Your doctor may or may not have an opinion and will probably not want to get involved.

A gallon of pasteurized milk costs around $3. A gallon of raw milk costs around $7-$14 and as much as $6/quart for goat milk ($24/gallon). Goat milk and cow’s milk are both good for you. Still cheaper than drugs. Always start out slowly — you’re modifying your gut microbiome. Throw away your Lactase. Once you’ve re-introduced the microbes you need to digest milk, you may be able to enjoy store-bought ice cream and milkshakes again.

The people who have the best health care plans are those likely to suffer the most. Frequent doctor visits means more antibiotics. That doesn’t count the mini-doses we get from beef, chicken, turkey, etc. Over half of the antibiotics sold in the U.S. are fed to livestock. It makes them fatter and lowers contagious infections.

Speaking of growing fatter, did you ever wonder how someone who weighs 700 pounds could possibly find enough hours in the day to eat that much food? They can’t. Their gut microbe makeup is slanted toward absorbing more calories from their food. The really crazy part is that the microbes in your gut affect your brain chemistry. I’ve read that there’s more brain chemistry (serotonin, dopamine, epinephrine, etc.) in your gut than in your brain. It’s called your “second brain” and it gives you your gut reaction and intuition. The microbes in your gut want to live and thrive. They will tell your brain what to crave — it’s what they crave. Once you sway your microbiome to flourish on sweets by eating them too often, they’ll tweak your brain to chase sweets. Or vegetables. Or fats. Or whatever you’ve overdone. Or just as the result of trashing whole varieties of microbes with oral broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Lab trials with mice have found that fat mice get thin and thin mice get fat when they swap some stool. Human obesity trials are underway. Some may be slanted toward failure, for obvious reasons. A cheap pill that really causes you to lose weight? Who would that upset?

I’ve also read that some microbes have the ability to turn some genes on and off in your DNA.

So you’ve been eating a lot of (some foodstuff). The microbes that favor that food multiply. They modify your brain chemistry to eat even more of that food. Then they edit your DNA to absorb more from that foodstuff (technically, it looks like they tweak dormant genes). Still wonder why so many Americans are overweight? This is why diets don’t work; they don’t get to the source of obesity — the lack of diversity in your gut.

Think of gut microbiome diversity as if it were a rainforest. The more variety, the healthier it is. No “one thing” can take over because there are so many different species to keep everything in check. We suffer because our diversity is limited and lost.

Fortunately, unlike the extinction of species in a rainforest, we can have FMT’s. See:

https://www.google.com/search?newwindow=1&ei=ZvHuW-SpPKG5gget37K4Aw&q=fmt+fecal&oq=fmt+fecal&gs_l=psy-ab.3…32660.34578..34994…0.0..0.137.696.2j4……0….1..gws-wiz…….0j0i71j0i67j0i20i263j0i22i30.PdhlT35_8bk

If you’re going to get a round of antibiotics, you might consider “stool banking.” Same as donating your blood for your upcoming surgery. In my opinion, any doctor that gives you a round of antibiotics without banking your stool or making some plan to replace the valuable microbes he just trashed is negligence.

Some doctors have access to freeze-dried stool for transplant:

https://www.openbiome.org/about-fmt/

ANY donor should be properly screened for diseases, parasites, etc. No sense compounding your problems.

The safest FMT at home is Poop Pills from a safe donor:

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=poop+pills

and:

https://www.google.com/search?newwindow=1&ei=jPHuW9TuEeON_QbYg63gCA&q=poop+pills&oq=poop+pills&gs_l=psy-ab.3..0l2j0i67j0l7.270133.271997..273598…0.0..0.179.1308.0j10……0….1..gws-wiz…….0i71j35i39j0i131j0i131i10.7jGBNgmW5Lk

Poop pills are basically two layers of gelatin capsule dipped in melted beeswax to remain intact until they’re far along your digestive tract. You really don’t want stool in your stomach — it doesn’t belong there.

Speaking of which, fibromyalgia and IBS are becoming recognized as the right microbe in the wrong place. The name is SIBO — Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth.

https://www.google.com/search?newwindow=1&ei=0_PuW-rBH9Ca_Qb6n4yQCQ&q=sibo+fibromyalgia&oq=sibo+fi&gs_l=psy-ab.3.1.0l5j0i10l5.1917343.1922796..1925448…1.0..0.149.1068.0j8……0….1..gws-wiz…..6..0i71j0i131j0i7i30j35i39j0i67j0i131i67j0i20i263.823ipYs9pbc

Just last week, NPR’s Science Friday had a segment on the changes that occur when healthy people from other countries come to America. They eventually suffer from the same diversity losses that all Americans have. Successive generations are affected even more.

https://www.sciencefriday.com/segments/wherever-my-microbiome-may-roam/

As for the worst thing you can do to a newborn, C-Section birth seems to be at the top of the list. Mom’s birth canal gets modified a few weeks before birth to mimic the microbes in her gut. The newborn is awash in these microbes, and transfers them to mom’s breast, where they continue to dose him at every feeding. Also, babies are born face-down, which exposes them directly to the microbes near her anus. All totally harmless and vital to the newborn’s developing immune system. And then they get raw milk. (The first feedings also contain colostrum, a vital nutrient not found in infant formula.) A C-Section baby has skin-type microbes in their gut, from the adults that handle them. They start out at a loss, and develop autism, altered brain development, asthma, bee sting allergies, nut allergies, dust mite allergies, pet hair allergies, and the list goes on and on. (I know, I know. I’m gonna get some real haters on the autism remark. Do the math. It’s not vaccines; it’s the people who have the best access to vaccines. People with terrific health care plans. People with deluxe access to C-Sections and antibiotics and hand sanitizer and ultra-clean homes. And certainly no playing in the dirt in the back yard. Don’t get me wrong, parasites and contagious diseases live in animal poop in the back yard. But lots of harmless microbes live there, too.)

If these links don’t work, just look at them closely and you’ll see where to go and what to search for. If you’re a little PC-savvy, you can click-and-drag over the entire string, simultaneously press CTRL key and the C key on your keyboard to copy (called a HotKey), click on the URL address on a new tab to highlight it, press CTRL and V to paste, then Enter to go to that page.

Love Chuck’s rant, almost as good as the article itself.

I would have preferred more detail in how exactly this was done, where did you get the saline from etc? It seems hard to believe that this could be cured with one FMT session.

Clinics here in the UK want you to have up to about 10 sessions, each of which is very expensive, so someone doing this at home is gold, but more details are needed for us scaredy cats who want to try this but need a bit more info.

Chuck Gosh, sooooo, are you telling us that drinking raw milk will fix the bad bugs in my gut? I need to know all I can about this please!!! I have had C diff four times and just completing my last go around of Vanc with little hope of keeping the C diff at bay!!!!

Have found only two Docs that will do a FMT in Houston, Tx and it will cost me thounds of $$$. But i guess that will be better than death

Susan thanks sooo much for telling us your story and what you delt with to get well

Susan, excellent article. It’s so frustrating when the medical community throws around the word “quackery” inappropriately – and usually it just means they’re not current on the research in their field.

It is a common practice employed by Vets in bovine practice.PP

Probiotics and probiotic foods don’t work? Why?

I enjoyed reading Chuck’s comments, but would like to remind him (and everyone who writes about bacteria) that the word is PLURAL so one should refer to “a bacterium” !

I had CDiff 4 years ago after rounds of antibiotics for sinus infection and a final tragic round of antibiotics from a gastroenterologist who prescribed yet more antibiotics for

“overgrowth of bacteria” in my bowels. My primary care doctor prescribed Vanco and “ poo-pooed” me when I resisted. I have very serious reactions to certain antibiotics and am afflicted with hearing problems. Terrified of the Vancomycin side effects

including ototoxicity, I forged on alone in search of a fecal transplant. Miraculously ( because of my hearing issues and antibiotics dilemma) I fit the parameters for an “FDA approved study” in my hometown and had a transplant 2 weeks later. The kind doctor who performed the procedure patted my arm before the procedure and told me he was going to cure me. He told me the odds of the transplant vs antibiotics and that the transplant would win. He was right. The next DAY I was cured. After months of feeling run down and 2 bouts of CDiff I was normal again. The only “side effect” I experienced was that my own poo smelled a bit different now that I was happily harboring a healthy donor’s microbes. But I wouldn’t trade it for the world. I know it saved my life. Since then a friend of a friend had CDiff and I helped her find a donor transplant at a clinic in Vhicago because she had never heard of this procedure. She was headed for her deathbed yet her doctors failed to mention the lifesaving procedure.

( I ended up leaving my primary care doctor after his callous attitude towards me even after the successful transplant. )

The 1,200.00 prescription of Vanco is still sitting in a box on a on back shelf because before I took it I decided to “heal thyself.” So Big Drug cashed in on me but I didn’t go all the way with them. Shame shame on FDA who shares the same bed as Big Drug. More people are dying of CDiff than MRSA these days and people continue to die because of politicing and profits over people. My procedure cost me a mere $200.00 out of pocket and my insurance covered the rest which was equal to the cost of a colonoscopy. I pray others have the resources to and courage to save their own lives. We all need to recognize that if our doctors “poo- poos” us about CDiff- we should flush them down the toilet. My prayers to all and their families who are battling CDiff. Only through our voices will we make a difference. And telling my story is a tiny step in doing that.

Big Ag runs the Dept of Agriculture. Big Pharma runs the FDA. The private prison system will soon be running parts of the Justice Dept and ICE. This is capitalism in the USA.

Hi Chuck

Interesting insight. I kinda like your take and personally believe in that line of thinking.

Its obvious you have done quite a bit of research. Any blog where you discuss such content.

Will be interested.

Thanks

DS

It just goes to show that we, individually, are in charge of our own health. You can’t depend on a harassed and overworked doctor to figure out during your 15 minute appointment how to treat something so complex. I have multiple ailments and research everything and ask my doctor as a trusted advisor about treatments. If s/he won’t listen, I get a different doctor.

My grandfather, who was a doctor abot a century ago dealt with cholera epidemics. He used to tell me how the water in cholera contaminated wells used to gradually become safe to drink. He used to explain that this was due to “phage”- organisms that fed on cholera vibrio bacteria. In fact he also talked about himself and a few others administering highly diluted cholera stools (which were very watery anyway) to patients. Many recovered, but they did this out in remote villages – not in any hospital, so it did not qualify as an experiment.

I found the article fascinating – almost my grandfather talking.

You are so brave to have undertaken this on your own! Brava!

Informative article.. and dear Chuck Ghosh, thanks a lot for the additional info. True! It’s so hard these days to find a good doctor that thinks about the well-being of their patients instead of filling up their own pockets with blood money. Same goes for our big corporations and politicians/policy makers

Two responses and a suggestion . . . (sorry for the lengthy rant, but people’s lives are on the line).

First, the reason we’re disgusted by poop is the smell of cadaverine. A by-product of a specific bacteria, it’s the scent of a cadaver. That microbe is already in everyone’s gut but never gets a chance to flourish (same situation as c. diff.) until something dies. It’s also a scent found in poop. We are genetically taught to run the other way when we smell cadaverine.

Second, the behind-the-scenes reason the medical community is unwilling to give fecal transplant a fair trial is that it may well cure over a thousand “diseases.” Auto-immune disorders are caused by your own immune system attacking your body. Your immune system is “trained” by the assortment of ~35,000 different microbes in your gut that it sees every day — they attack anything new that’s not found there. Consider it a harmless chronic infection. After a lifetime that includes a dozen rounds of antibiotics, some college-age drinking binges and the following loose damaged stool, too much hand sanitizer that accomplishes nothing unless you’re in a disease ward, and a nearly sterile environment that never allowed you to obtain the harmless colon microbial diversity your body craves, you’re left with a mix of 20,000 or so that doesn’t give your trigger-happy immune system much choice but to start attacking all kinds of harmless objects and their foreign microbes (meaning pollen, perfume, FD&C yellow #5, milk, wheat, and “you”).

The prospect of swapping out a drug that treats your “incurable” auto-immune condition (for $20,000+ a year in insurance payments — just Google “how much does [any drug you see advertised on TV] cost”) with a single treatment that costs a few hundred bucks and a few hours of your time is more than any self-respecting pharmaceutical CEO can stand.

Type II diabetes is not caused by your pancreas failing; it’s caused by your own immune system attacking your pancreas. Asthma is unpleasant, but the immune response from your own body can quickly bring death.

Imagine a hospital Emergency Room that suddenly had no asthma cases. Or diabetic crises. Or anaphylactic shock from a bee sting or food allergy. No life-threatening reactions to pet hair. Or fibromyalgia, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel disorder, Crohn’s disease, gluten intolerance, lactose intolerance, c. diff., and a thousand other incurable “diseases” that are completely non-contagious, have no cure, no known cause, and will require regular (expensive) drug dosages for the rest of your life just to treat the symptoms (along with many dangerous side-effects, including death). If you can find a drug that helps at all.

Fecal transplants will cure too many people. Overnight. That destroys the status quo. Overnight.

Now you have some idea why the FDA — which gets their budget from pharma companies to test new drugs — has no interest in fecal transplants, and in March, 2013, stopped them altogether. A massive outcry from the public caused them to reverse their edict a month later, but it’s still nearly impossible to find a doctor with the correct credentials to do a research “transplant” (yeah, classified as though you were getting a donor organ, when it’s actually somebody’s lunch, not their heart). A blender and funnel in your kitchen is a YouTube favorite topic. Watch Grandpa save Grandma’s life while their grandson shoots their first and only video for upload. Their doctors are aghast, but will lose their license if they get involved; all they can do is point them to the YT videos.

One of the problems is that you can’t patent poop, though the University of Guelph in Ontario is trying to mix up a standardized batch with their Re-Poopulator equipment. And, as mentioned above, an MIT spinoff makes freeze-dried overnight parcels available. But not to you and me.

Meanwhile, the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) tries to slow or stop fecal transplants while the NIH (National Institutes of Health) gives research money to universities to study them. Your tax dollars at work.

If you are suffering and are willing to part with $10,000 you can try Taymount Clinic north of London. YouTube videos of their cured IBS/IBD/UC/etc. patients tell you everything you need to know. It’s only about 2 grand for Brits, since their socialized (civilized?) health care system pays the rest, saving taxpayers untold sums in future expenses. These people are cured of a list of incurable diseases.

For the rest of us, try a few months drinking raw milk. It’s been a popular beverage for about 10,000 years, ever since people began farming. A few older societies exist solely on a variety of foods made exclusively from raw milk. It’s loaded with beneficial microbes that improve your immune system (that’s why we have always given it to all our babies). When you see a documentary showing people with a goat or a cow, they’re not keeping them around for the meat. Why do you think they have all those sacred cows in India? Check RealMilk.com for your area (get it? Real Milk?). Even if you’re allergic to milk, you’ll quickly discover you’re actually allergic to PASTEURIZED milk, which has had all its enzymes and microbes destroyed, making it much more difficult to digest. Raw milk spoils into lots of other dairy products. Pasteurized milk rots. You can thank your (name of your state goes here) Milk Producers Association for scaring you into thinking that obtaining milk directly from a farmer will kill you. Seriously, when was the last time you heard about someone getting sick from raw milk? 1933? Chicken, Chipotle’s, deli meats, peanut butter, spinach, ground beef — those are the foods that have the recalls because they poison people.

You eat raw foods all the time. Drinking pasteurized milk is a very new practice by humanity. All mammals (except people) drink raw milk, and they always will. They seem to be doing fine, and the fact that we’re here to talk about it means it wasn’t bad for us, either.

If you’re still grossed out by the idea of raw milk, give it time. If you’re suffering now, you will eventually get to the point where you’ll try anything to stop the pain. It’s your call.

This is a fabulous insight to the willingness of physicians to perhaps think out of the box. Due to the fact that physicians have over prescribed antibiotics the general population cannot combat the antibiotic resistant strains that have developed. I am a healthcare practitioner and understand this dilemma and it’s consequences. It is terribly disappointing that it comes back to “patient heal thyself”. But if that what it takes then one must do what they have to do. I firmly believe that physicians do not listen to patients anymore, apparently they know better.

How egotistical is that? Each one of us is well aware of our bodies and have a very keen sensibility to when something isn’t right. If one is a true scientist they would not brush away something they themselves don’t understand or comprehend but actively find a solution.