Science and technology often seem to be cogs in a relentless wheel of progress: Someone discovers something, a contraption incorporates the idea, and business prospers. Then someone improves on that idea, and the new things replace the old ones. But wine, it turns out, is a subject that doesn’t neatly fit that chronological model.

WHAT I LEFT OUT is a recurring feature in which book authors are invited to share anecdotes and narratives that, for whatever reason, did not make it into their final manuscripts. In this installment, Kevin Begos shares a story that was left out of “Tasting the Past: The Science of Flavor and the Search for the Origins of Wine,” published this week by Algonquin Books.

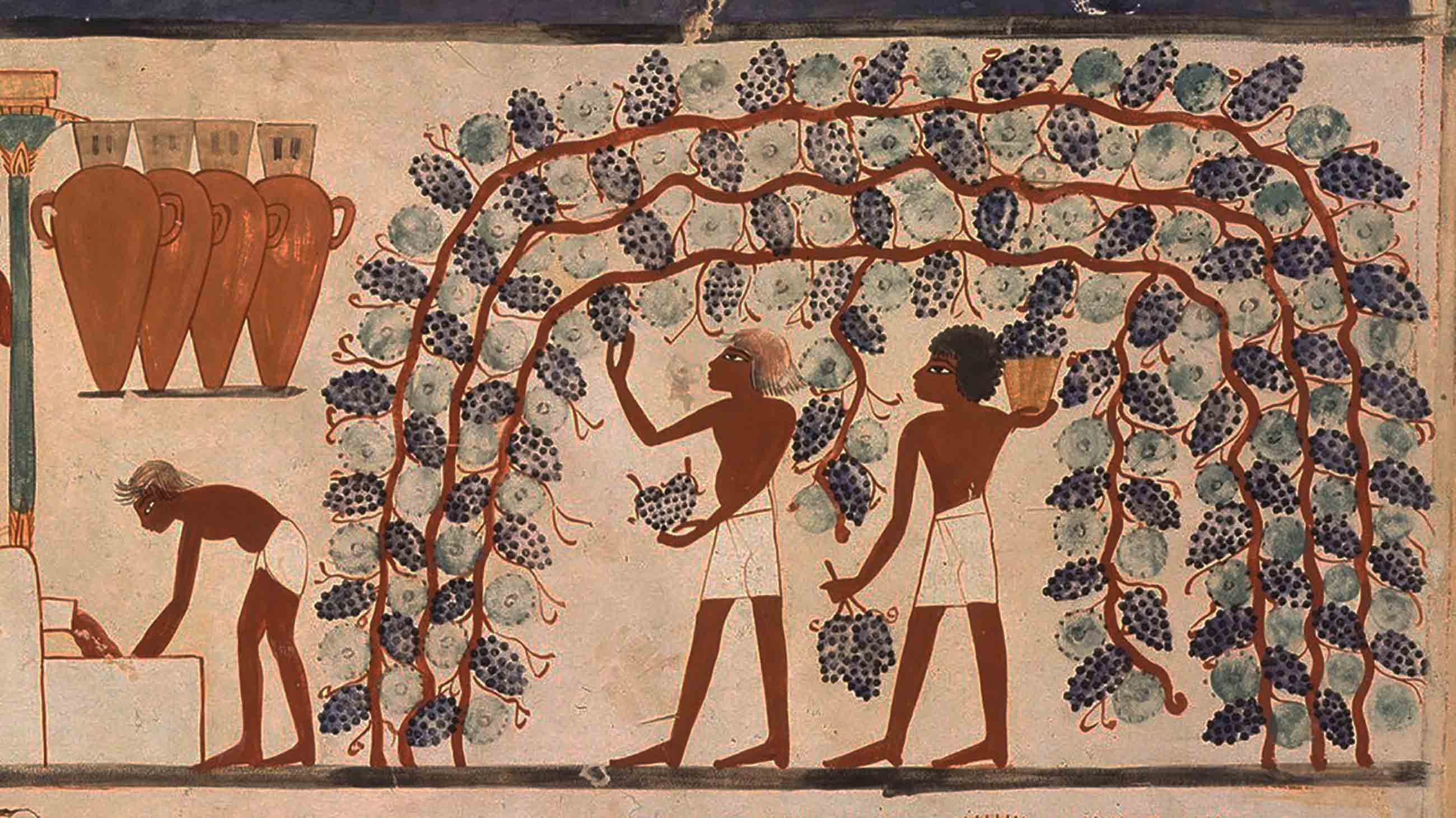

About 6,000 years ago, people in the Levant (a region that today includes much or all of Israel, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, and the Palestinian territories) began to domesticate olives and grapes. The wild fruits tended to be small and bitter, but over the next few millennia people began to notice and cultivate trees or vines with larger, tastier fruits. Phoenician traders spread these varieties far and wide, transforming natural bounties into global industries; vast quantities of oil and wine were exported throughout the Mediterranean.

To learn more about this story, I visited Rafael Frankel. An expert on the history of wine and olive presses, he lives on Kibbutz Beit HaEmek, in northwest Israel — just under 10 miles from the Lebanese border, near the coastal cities of Tyre, Acre, and Haifa. The region was home to the Phoenicians, and thus at the heart of the forces that spread wine, oil, and ideas. Frankel was 86 when I interviewed him in 2015, and, he told me, “I’ve spent the last 40 years dreaming” about the presses those ancient producers used.

There is general scholarly agreement — recently supported by DNA analysis — that primitive winemaking began about 8,000 years ago in the Caucasus region, somewhere between northern Iran and eastern Turkey. Yet the oldest confirmed evidence of production — a 6,000-year-old site inside an Armenian cave — was set up to produce only a few gallons, most likely for ritual use (the cave was also a burial site).

It was the Hittites and the Egyptians who learned to exploit the magic of fermentation — yeasts transforming grape juice into alcohol — on a large scale. They planted enormous vineyards and refined methods to produce, store, and transport wine. The knowledge spread from East to West; organized winemaking didn’t reach France until about 500 B.C. (Yes, the French are new kids on the block.)

Frankel was attracted to the subject because archaeologists have found so many varieties of presses in the Levant. One might have expected the most primitive presses to be the oldest, with a steady progression of newer models over the centuries. But as he studied various sites, he slowly came to a startling conclusion: The age of the presses didn’t seem to correlate with technological advances; in some parts of the Levant, older technologies persisted long after they had become obsolete elsewhere.

The most primitive form of wine press wasn’t actually a press, even though the Hebrew word “gat” is often translated that way. “I think the term is misleading,” Frankel said. “Because it isn’t a press — it is a flat treading floor,” in which workers pressed the grapes with their feet and the juices flowed down to a vat. The earliest examples in Israel date to about 4000 B.C.

Soon olive and wine producers began using large wooden levers weighted with stones to extract even more oil and juice, and there were variations in the types of stone mortises that enabled the whole mechanism to work. They later added screws to squeeze out every drop of juice (the earliest screws were wooden, too). The traditional archaeological method would have been to organize the wine press research by date, from the oldest to the newest. But the maps Frankel made told a different story.

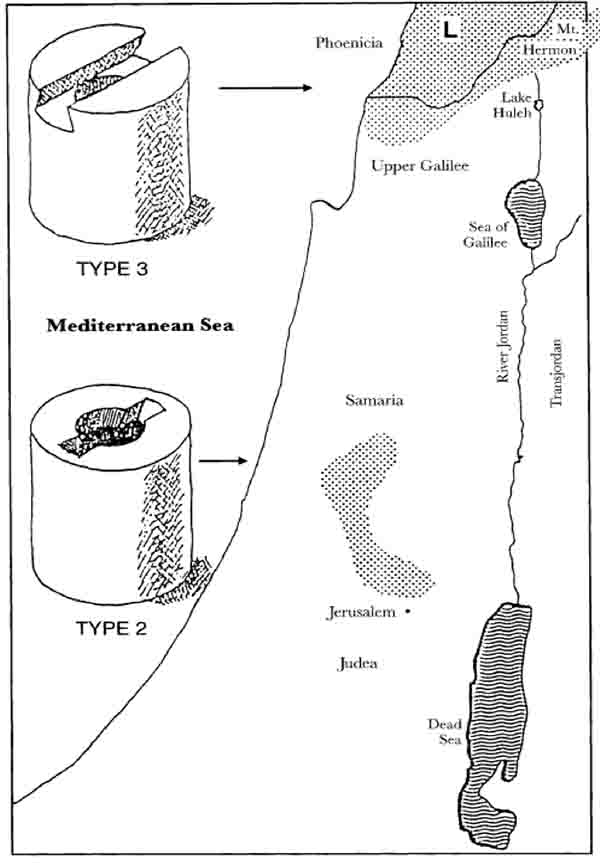

“What I found was, even in a little country like Israel, … there are differences between the different regions,” he said. And those differences were absolute: For example, people who used what Frankel calls a Type 3 design were all in the north, and those who used a Type 2 were in the south. Local traditions took precedence over technological advances; even where there was overlap in press design, rigid boundaries appeared. Some villages had certain types of press on one side of the street, yet on “the other side of the street, it doesn’t appear,” Frankel said, adding:

“Quite unbelievable. As a result, I analyzed the story less by dates, but more by the geographical position of the various types. It works not by chronology, but by typology.” So his books and papers are full of maps.

Frankel’s maps illuminated other aspects of ancient societies. “Two exceptional weights were found in monasteries and were almost certainly introduced to the area by monks from abroad,” he said. The Jerusalem region features a remarkable variety of technologies; Frankel thinks that’s because the city had so much contact with foreign cultures, and was thus a mixing place for new ideas.

Frankel believes the patterns suggest another counterintuitive history. One might have expected that the societies that first developed primitive presses would also be the quickest to develop more efficient variations: After all, they had the longest period of time to do so. But perhaps people without the oldest traditions were more open to new ideas. For example, Frankel believes that one evolution in screw-press design that appears outside the Levant is an example of “conceptual transfer.” He suggests it happened because “at a very, very early stage the Phoenicians saw people using the screw, and they came home and told their cousins,” who modified and improved the design.

One of Rafael Frankel’s maps, showing the distribution of weights used in wine presses in the region that later became Israel and Lebanon.

Visual: Rafael Frankel

In contrast, some traditional press styles were used in the Levant not just for hundreds of years, but for millennia. Frankel believes those are examples of “complete transfer” — situations where installations closely copy what came before in that locality.

I asked whether people might have treated certain press designs as secrets, but Frankel sees something else. “That’s how my father did it — that’s the story” of wine- and oil-press traditions, he said. “Until my generation, you used to ask your grandfather how to do things.” (Nowadays, you’re more likely to consult the internet.)

“Don’t forget, most people were farmers,” he continued. “It wasn’t just agricultural food — it was culture, and art, and religion, and everything. In those days, everybody trod the grapes, and everybody trod the olives. It’s quite different from the world we’re living in.”

Winemaking didn’t change much in the Middle East until the late 1800s, when Baron Edmond de Rothschild (a Frenchman) brought new techniques and ideas to the Israeli wine industry. Yet traditions persisted: Some of the ancient-style troughs were still being used to make grape syrup in the 1990s, in the Hebron area of the West Bank. And when Frankel expanded the research to include sites throughout the Mediterranean, he found that geography was a surprisingly strong force. Various regions from Spain to North Africa had presses that fell into patterns. He believes those may date back to provincial boundaries drawn in Roman times.

Imagine a modern parallel: If everyone in Massachusetts used Windows PCs, but people in New Jersey used Macs; or if Ford trucks were exclusive to one region, and Chevys to another. I asked Frankel what cultural forces could have inspired such absolute differences between types of press. “Basic conservatism,” he said about tribes in the ancient world. “They spoke different languages.”

One could argue that Frankel’s theories about the strength of tradition apply only to ancient cultures, but another conversation in Israel suggested that isn’t true. Yiftah Perets, a winemaker at Binyamina Winery, one of Israel’s oldest, told me he still finds inspiration and knowledge in ancient wine installations and ancient texts. “I must say it’s helped me a lot in my professional life,” he said.

Perets has been creating his own maps that show where ancient wine presses were located. “For example, on this hill, which is about one square kilometer, we found seven wine presses. Here we found more than 10,” he continued, pointing to another. “You can see that each wine press is in the middle of a terrace zone. And for me it’s amazing. What I try to understand is why.

“And what I found out is that in this area all the good soils were used for olive oil, and wine was second. So the farmers must understand before they plant. So this is the base of understanding the old Jewish way of making a vineyard.”

Perets has also followed DNA research on Israel’s native grape varieties, and he thinks modern technology doesn’t hold all the answers to making fine wine. “The solution is sometimes next to your door,” he said, speaking of the things he has learned by studying ancient winemaking.

Nor is he the only one embracing old traditions in the computer age. Winemakers in the Republic of Georgia are proudly emphasizing their use of clay containers called qvevri to ferment and age wine — a practice that goes back roughly 8,000 years. Winemakers in Italy, France, and even Oregon are doing the same.

But the old stone and lever presses that Frankel studied? They aren’t coming back in vogue — at least not yet.

Kevin Begos is a former Associated Press correspondent and a contributor to “A Field Guild for Science Writers.” His work has appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, and many other newspapers.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Peter, this passage from my book Tasting the Past suggests a reason:

McGovern and Vouillamoz kept looking, and found that linguists who examined the origins of the word “wine” discovered an interesting parallel. In a broad range of languages, from ancient to modern times, “wine” appears to stem from a common ancient root word with origins in the Middle East. From Hittite to Akkadian, early Semitic to Hebrew, and ancient Egyptian to Greek, there is evidence the word woi-no or perhaps wei-no, inspired the word for wine in many other languages.

Peter, this passage in my book Tasting the Past suggests the reason:

“McGovern and Vouillamoz kept looking, and found that linguists who examined the origins of the word “wine” discovered an interesting parallel. In a broad range of languages, from ancient to modern times, “wine” appears to stem from a common ancient root word with origins in the Middle East. From Hittite to Akkadian, early Semitic to Hebrew, and ancient Egyptian to Greek, there is evidence the word woi-no or perhaps wei-no, inspired the word for wine in many other languages.”

I am curious why wine has a very similar name in most area outside of the Middle East as if a common set of people was trading it around the Middle East.

Another thing I find a little unusual is that Osiris who was the Egyptian God of the Dead who was supposed to have taugh man wine making was called Wennefer. Kind of seem coincidental that his name is similar to wine.

Well as the author did point to in the article…the region of ancient Iran, Iraq, and Turkey is believed to show the first evidence of wine making around the area of the Zagros Mountains. This would have spread early to Afganistan region as well.

This seems like a very Israel-centric tale of wine, although given my ignorance on this subject, perhaps that’s where it all developed. When I was in Western China several years ago I came upon massive varieties of raisins at the markets https://www.tripadvisor.com/LocationPhotoDirectLink-g297466-i24398519-Urumqi_Xinjiang_Uygur.html –someone on the trip (they were all tomato growers and processors) told me that grapes had originated somewhere in that region, perhaps in Afghanistan. I never checked, but it is true that expansive genetic diversity often indicates where a species originated.