At the height of the French Belle Époque — a Renaissance-like era that straddled the 19th and 20th centuries — two pioneering women lived in Paris just a few miles apart. The Polish physicist Marie Curie spent her days at a lab bench, discovering luminous new elements that would one day alter history, while the American dancer Loïe Fuller staged shows that entranced crowds with their ever-shifting interplay between movement and light.

On the surface, the two women couldn’t have been more different. The introverted Curie preferred titrating chemicals to attending parties, while the charismatic Fuller thrived on press accolades and the social whirl of gaiety. In “Radiant: The Dancer, The Scientist, and a Friendship Forged in Light,” science writer Liz Heinecke, a former molecular biology researcher, explores the evolution of Curie and Fuller’s unlikely friendship, and the ways their shared love of light spurred both of them to ongoing discovery.

BOOK REVIEW — “Radiant: The Dancer, The Scientist, and a Friendship Forged in Light” by Liz Heinecke (Grand Central Publishing, 336 pages).

Luminescence shaped both women’s career paths long before they met one another. Fascinated by the energy beams, or X-rays, that came from the element uranium, Curie worked tirelessly to isolate other elements that emitted such rays, including radium, which gave off a teal-green glow in her lab beakers. She and her husband, Pierre, also developed a way to measure the energy coming from radioactive elements. Soon after the turn of the century, people were toasting Curie as the grande dame of radium and radioactivity.

Fuller made a name for herself with the innovative lighting effects she’d designed to accompany her dances. She fashioned a series of tinted glass disks with dried gelatin on their surfaces, which caused light to undulate as it shone through the spinning disks. The layered colors and textures transformed her fluid motions. “Standing over a glass trapdoor,” Heinecke writes, “she burned red, yellow, and blue, lit by brilliant spotlights that turned the silk of her robes into flame against a black background.”

Though Heinecke writes vividly about both women’s creative achievements, she gets somewhat bogged down in minutiae at the beginning: At one point, she has Fuller recite her autobiography to a visiting reporter, repeating material that has already been covered. As a result, we don’t get to see Curie and Fuller meet in person until nearly halfway through the book, though Heinecke draws out their initial letter exchange with cliffhangers to keep readers guessing when their first encounter will happen.

Thankfully, the pace picks up from there. As she recounts how Curie and Fuller forged their bond — which began at a dinner party Curie wasn’t eager to host — Heinecke captures the initially halting rhythm of their friendship, which smoothed out as they realized their shared views on the rewards of failure. Heinecke also highlights one of the most striking parallels between Curie and Fuller: the way that both, as women staking out new intellectual territory, faced pushback from male heavyweights who sought to deny them ownership of their breakthroughs.

When Curie presented her world-changing discoveries to French scientists, many insisted on attributing them to her husband, Pierre. Meanwhile, Parisian theaters often hired mimics who ripped off Fuller’s innovative lighting techniques; one male owner even insisted Fuller don a blond wig and appear onstage as one of her imitators. Commiserating about these kinds of encounters likely cemented the bonds between the two women, though the precise content of such conversations has mostly been lost to history.

Heinecke merges Curie’s and Fuller’s stories by describing how their deepening friendship launched each of them to new heights. Thanks to Curie’s advice, Fuller was able to extract luminous salts from a radioactive ore called pitchblende. She soaked fabric in a mixture of the salts to create dance costumes that appeared to glow from within. And during the First World War, when Curie created a mobile X-ray clinic to treat injured veterans, Fuller pulled some strings and convinced a wealthy friend to fund the novel venture.

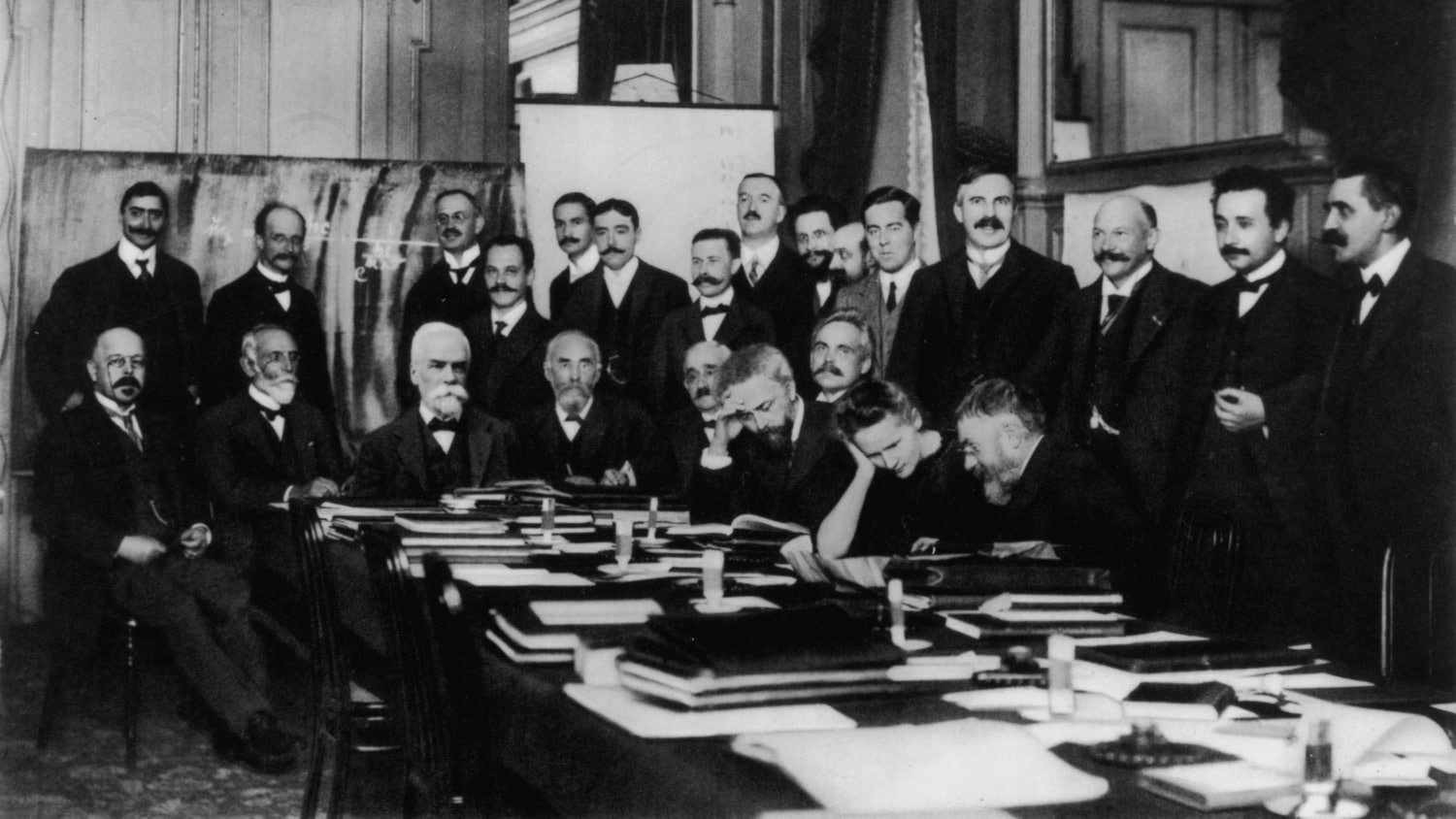

The fertile exchanges Heinecke describes — not just between Curie and Fuller, but between Fuller and Thomas Edison, and the Curies, Fuller, and sculptor Auguste Rodin — give a sense of just how common, and fruitful, cross-disciplinary collaborations were during the Belle Époque. In today’s academic environment, the walls between disciplines — the insider vocabulary, the years of study required for entry — diminish the odds of such cross-pollination. “Radiant” presents an impassioned case for bringing it back.

At times, the narrative ventures into the fuzzy borderland between creative nonfiction and historical fiction. Heinecke purports to know what Curie and Fuller are thinking, and she specifies in an author’s note that her dialogue is mostly invented. While the historical record may well support some lines of created dialogue and presumptive trains of thought, it’s difficult to tell which parts of the narrative are most solidly anchored in fact.

The story takes on an air of Greek tragedy as the substances that sent both women’s careers soaring degraded their bodies at a cellular level. Curie and Fuller worked with radioactive elements during a kind of Wild West era, before the elements’ immense power had been brought to heel, and both died relatively young. Marie developed a form of anemia tied to radiation exposure, while Fuller succumbed to pneumonia after months of ill health, possibly due to her own encounters with radioactive compounds. “Perhaps,” Heinecke speculates, “radioactive salts had been killing the dancer from the inside, like a silkworm cocoon dissolved by the moth within?”

Curie, at least, had an inkling of what she might have done to herself, and how her discovery had become a source of destruction as well as illumination. Disturbed by the fate of the so-called “Radium Girls,” who licked their brush tips as they painted glowing figures on clock dials, Curie spoke out late in life about radioactivity’s health hazards, even as her own exposures threatened to consume her.

Throughout, Heinecke displays a poet’s understanding of the ways swift ascent can prefigure ultimate destruction. When Curie and Fuller donned the wings of Icarus, they did so unawares, and by the time they recognized the peril they were in, it was too late to descend safely. The most enduring message of “Radiant,” besides its tribute to the generative power of friendship, is that light can blind as surely as it can clarify.