Rise of the Lone Star Tick Brings New Disease Threats

Dressed in blue jeans tucked into gray socks and hiking boots, Jim Occi was prepared to round up some ticks from a New Jersey woodland. While some people might consider this a nightmare outing, it’s Occi’s idea of “fun”— he finds the arachnids fascinating, as proven by the tick tattoos on his forearms. It’s also useful because, as a microbiologist at Rutgers University’s Center for Vector Biology, he studies ticks and their diseases.

Occi marched along a forest trail, dragging a white muslin cloth attached to a PVC pole on the ground, working it through the leaf litter and along the grassy edges. Every few steps, he stopped to squint, searching for moving black specks that can be as small as a grain of sand.

New Jersey now hosts what Occi calls the “big five” tick species: blacklegged, lone star, dog, Gulf Coast, and the newly arrived Asian longhorned, most of which have been growing in numbers and expanding their range. These species “quest” for their hosts, meaning they perch in leaf litter or on a blade of grass with a pair of legs outstretched waiting for an animal, whether it’s a person, a small mammal, or even a bird or reptile.

“If anything comes by, they’ll just clamp on,” Occi said as he used the cloth on the end of the pole to mimic an animal shuffling in the underbrush. “They can’t hop, skip, jump, or fly — they have to have direct contact with the host.”

The species that he was hoping to catch, the lone star tick, doesn’t only quest — it also hunts. The lone star can sense vibrations and carbon dioxide emitted by a potential host. “They detect your breath and become alert,” Occi said. “And then you gotta watch out.” If a person sits down in a forest where they’re present, the lone stars will likely come crawling.

In New Jersey’s Monmouth County, on the southern fringe of New York City, the number of lone star encounters now surpasses those with blacklegged ticks, according to data collected by a county surveillance program that invites residents to submit ticks they pluck from themselves and their pets for identification.

Environmental conditions have tilted toward the lone star’s advantage, said Monmouth County tick researcher Andrea Egizi. The forests are recovering from decades of logging, white-tailed deer populations have rebounded, and winters are getting warmer due to climate change. “It’s kind of this perfect storm for them to be taking over,” Egizi said. Citizens in New Jersey encountered mostly blacklegged ticks until roughly 10 years ago, when the counts “switched over to being dominated by lone stars,” she added.

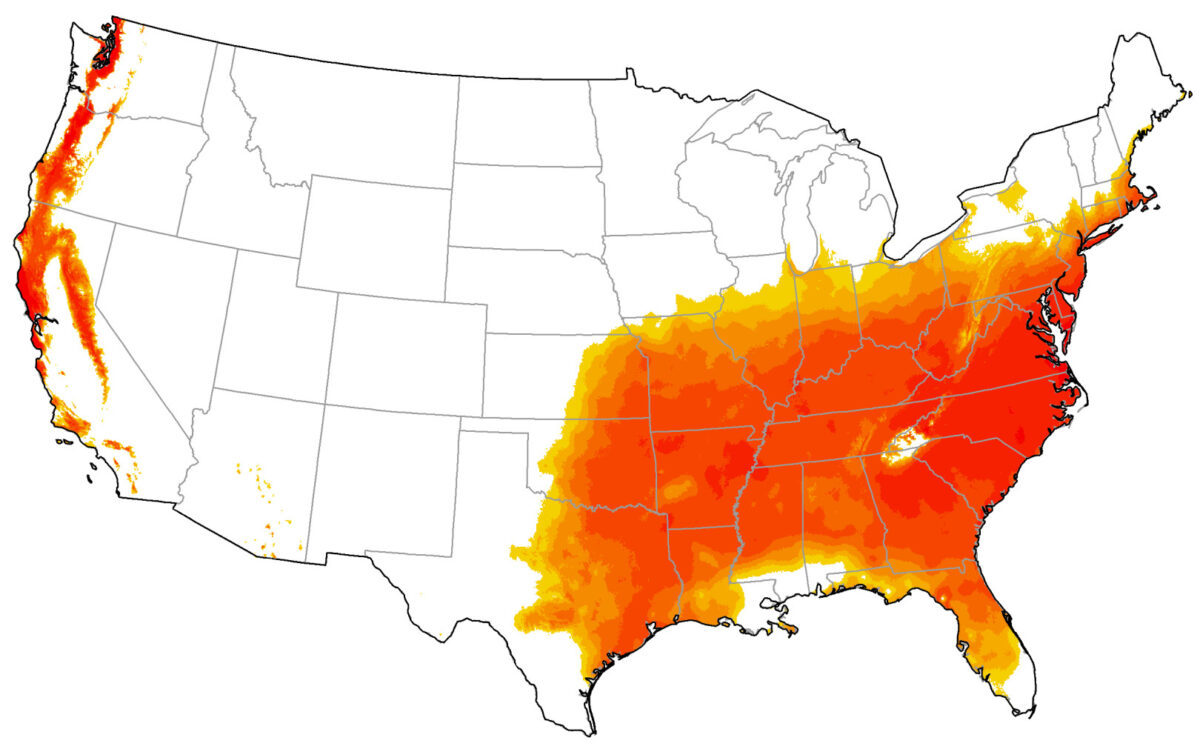

Research shows the lone star tick’s expansion has been progressing for a few decades; it’s now established from Florida to Maine and as far west as Nebraska.

“It’s kind of this perfect storm for them to be taking over.”

The rise of the lone star tick is alarming, say public health officials, because it carries novel maladies. These include a Lyme-like bacterial disease called ehrlichiosis, which first appeared in humans the mid-1980s; a meat allergy that sounds like a female superhero, alpha-gal syndrome; and the emerging Bourbon virus, first identified in humans around 10 years ago when a Bourbon County, Kansas man died after being bitten.

Diseases like Bourbon virus are, so far, very rare. But the combination of recently discovered disease-causing germs and expanding tick ranges have prompted a push for new research into a familiar pest.

“Tickborne diseases increasingly threaten the health of people in the United States,” wrote Alison Hinckley, an epidemiologist and vector-borne disease expert with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in an email to Undark. “Improved understanding about reported tickborne illnesses, expanding geographic ranges for ticks, and risk factors will help prevent and control tickborne disease.” New tools for preventing tickborne diseases are “urgently needed,” Hinckley wrote, and it’s important that people take steps to prevent tick bites.

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus described a copper-tinged creature with a single white spot in the center of the female’s body — the first tick to be formally described in North America. That white spot gave the lone star its name (not the state of Texas) and it was found throughout the Northeast until the 1800s, when the region was extensively logged and cleared for farming and tick host animals such as the white-tailed deer were overhunted. Consequently, the tick’s range shrunk to the southeast and south-central U.S. But now it’s back in the Northeast, threatening to topple from its longtime throne the better-known — and docile, by comparison — blacklegged species that transmits Lyme disease.

A likely factor influencing the lone star’s current northward expansion is climate change, say scientists, though more research is needed. One thing is clear, according to Rick Ostfeld, an ecologist and tick expert at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York. As he explained on the Colin McEnroe radio show in August, as seasons lasts longer — spring arrives earlier, and winter comes later — the ticks benefit because they have more time to find hosts and complete their life cycles.

Predicted suitable areas for the lone star tick in the U.S. in 2019, from high suitability (red) to low suitability (yellow).

This, combined with changes in land use and tick host populations, explains why Lyme disease, the subject of Ostfeld’s research, has rapidly proliferated across New England and the Midwest since it was first discovered in a cluster of children experiencing uncommon arthritic symptoms in Lyme, Connecticut in 1975. Today, Lyme is the most common vector-borne disease in the country, according to the CDC. The agency reported in 2021 that some estimates suggest as many as 476,000 people get treated and diagnosed with Lyme disease each year.

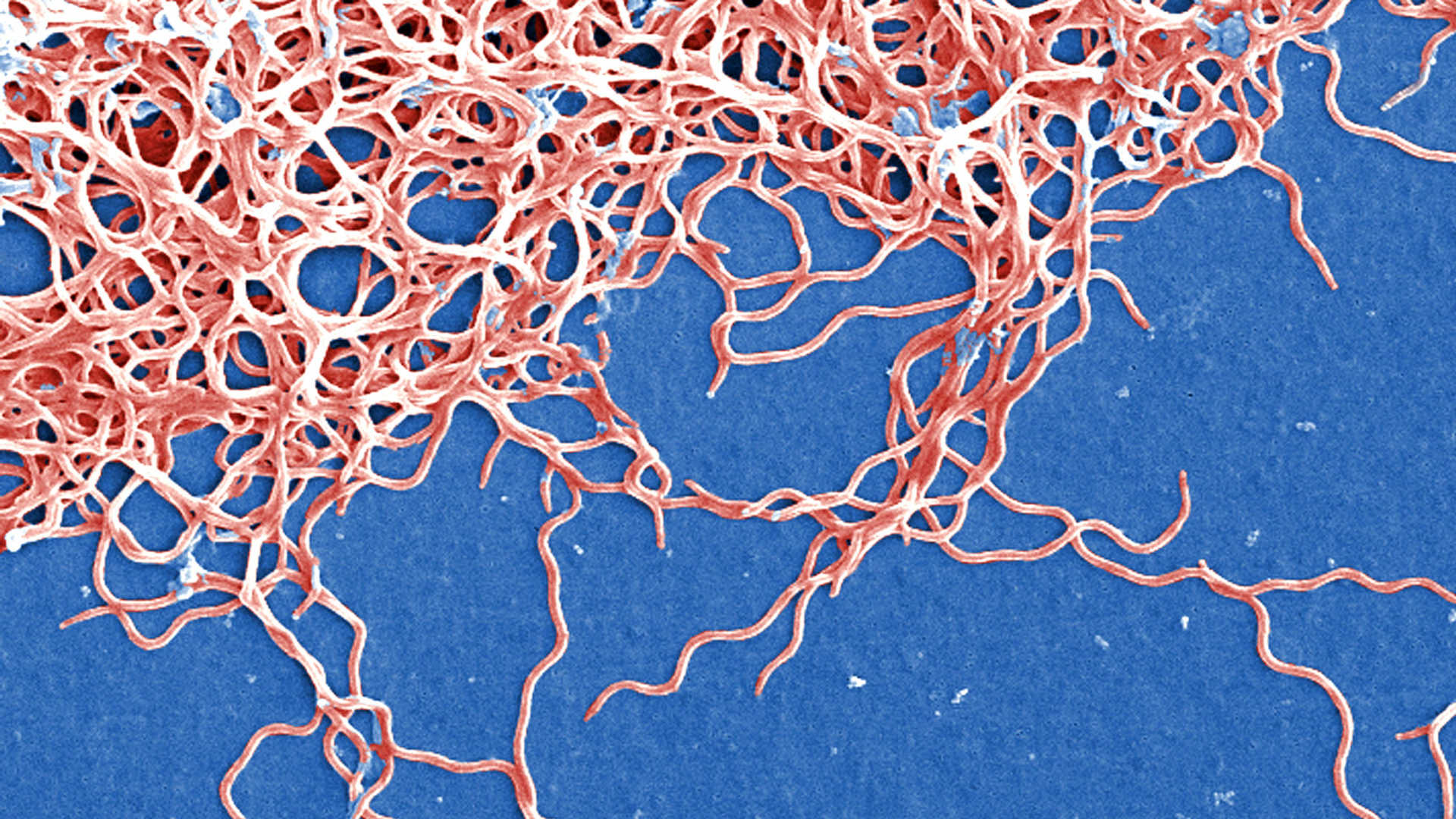

The mechanism for most tick-borne disease transmission is based on the arachnid’s life cycle, which has four stages: egg, larvae, nymph, adult. After an egg hatches, each of the next three phases must take a so-called blood meal from a different individual host. If a larval tick bites a wildlife host such as a mouse carrying bacteria that causes a disease, it becomes infected. After feeding, the larval tick drops to the ground and morphs into the nymph stage. The nymph takes a blood meal from a host, infecting it. Then the nymph morphs into a disease-carrying adult.

Oftentimes people don’t realize they’ve been bitten until they get sick. Larval and nymphal ticks pose a particular hazard because they’re so difficult to see; a larva is about the size of a grain of sand, a nymph is roughly as big as a poppyseed.

A bite from a lone star tick can trigger a person’s immune system and make them allergic to red meat. “They call it midnight anaphylaxis,” Occi said as he swept his white flag through a patch of stilt grass. “You go out to dinner, go to bed, and you’re like whoa, what just hit me?”

Occi was describing the onset of “alpha-gal syndrome.” Alpha-gal stands for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose, a sugar that’s found in red meat, including pork and beef, as well as certain animal products, such as milk and gelatin. It’s also found in the saliva of lone star ticks. When some people are bitten by the lone star tick, their immune system reacts to the alpha-gal, and then the next time they eat red meat, their antibodies produced in response to the tick bite go overboard and cause a hyperactive immune response similar to how a person allergic to bees responds to a bee sting.

Rachel Dickinson, a writer and artist who lives near Ithaca, New York, doesn’t remember being bitten by a tick. One day after eating lasagna with pork sausage, her throat started to itch, and then it felt like it was closing. “I got really scared,” she said, “because I thought ‘Oh my god, I’m not going to be able to breathe.’”

Dickinson took some Benadryl and sought immediate attention from her allergist, who did some testing. The result: Dickinson was allergic to red meat. Her primary care physician had seen such an allergy in only one other patient. Diagnosis: alpha-gal. She advised absolutely no more red meat, and recommended avoiding restaurants because of the risk of eating something that had been cooked on the same surface as red meat. “I hadn’t even really considered the implications of this,” Dickinson said. “It has completely changed the way I have to think about food, and where I eat.” She misses being able to eat what she likes. “I’m not used to thinking about food that could potentially kill me,” she said. Many people with such life-threatening allergies keep an EpiPen close by. “I carry one in my purse at all times,” Dickinson said.

In July 2023, the CDC reported that there were more than 110,000 U.S. cases of suspected alpha-gal syndrome in the period between 2010 to 2022. However, those numbers could be a gross underestimate, according to the agency, because not everyone with alpha-gal gets tested. Some estimates suggest as many as 450,000 people in the U.S. have been affected by the allergy.

The rise of alpha-gal has been getting some news attention lately, but there are other lone star tick illnesses that are more obscure. Ehrlichiosis is a Lyme-like disease, causing fever, chills, head and body aches, that even some doctors don’t know about. New Jersey scientist Egizi experienced this firsthand: “There was one time I had some kind of flu-like symptoms in the summer and I had to convince my doctor to test me for ehrlichiosis because I had been bitten by a lone star,” she said. “It was negative, but I thought that was fun because they hadn’t heard of it. They were like, ‘You want us to test you for what?’”

Fortunately, ehrlichiosis is treatable with the same doxycycline antibiotic that is most often used for Lyme disease. However, Egizi said, a common issue is misdiagnosis: If a doctor suspects Lyme disease, but the test is negative, they may not prescribe doxycycline.

There are five nymphal blacklegged ticks on this muffin, nearly indistinguishable from the poppyseeds. Because the nymphs — which can spread disease — are so small, people oftentimes don’t realize they’ve been bitten until they get sick.

Visual: CDC

Lone star ticks also spread several novel viruses. In June 2009, two men were admitted to a Missouri hospital with flu-like symptoms and treated for suspected ehrlichiosis. However, genetic analysis later revealed that they were suffering from a virus previously unknown to scientists. It became known as Heartland virus. As of November 2022, the CDC reports there have been at least 60 cases of Heartland virus from states in the Midwest, Northeast, and South. Most patients diagnosed with Heartland became sick in the warm months from May through September.

In June 2014, a Bourbon County, Kansas man who experienced Lyme-like symptoms after being bitten by a tick visited his doctor and was prescribed doxycycline. When his symptoms didn’t improve, he was admitted to a hospital, where doctors continued to treat him with doxycycline while running lab tests for all known tickborne diseases in the region. All of them came back negative.

His condition continued to deteriorate and 11 days after the onset of his symptoms, he died. A sample of his blood was sent to the CDC to be tested for suspected Heartland, but it was negative. Another new virus had emerged. It’s now known as Bourbon virus.

So far, there have been four more confirmed cases of Bourbon virus, including a second death: In May, 2017, a Missouri state park superintendent developed a fever and painful rash after being bitten by two ticks and died a few weeks later.

Scientists at Washington University in St. Louis are combing through the region’s woodlands to collect lone star ticks and test them for Bourbon virus. Their findings show one in 150 lone star ticks in the area carry the virus. They’re also testing blood samples from citizens in the area, and finding that some people have Bourbon virus antibodies, indicating that it’s possible to become infected without getting seriously ill.

“I’m not used to thinking about food that could potentially kill me.”

According to Occi, Monmouth County has recently found ticks that tested positive for Bourbon virus, but only in low numbers — “less than 1 percent of all the ticks we’ve tested,” he said. Current efforts to beef up tick surveillance in other states will be helpful, he wrote in a follow up email, because “you can’t attack a problem if you don’t know where and what the problem is.” Public education, provided by states and the CDC, to prevent tick bites is another important step, he wrote.

With so many potential illnesses spread by ticks, Occi takes precautions when spending time in areas where he’ll likely encounter them — intentionally, or not. He wears DEET bug spray and protective clothing, and always does a thorough “tick check,” including examining hidden areas like under armpits and behind knees and ears. (According to the CDC, removing a tick within 24 hours can vastly reduce the chance of contracting Lyme; other diseases may spread more quickly.) The only ticks he ever wants to take home are the ones he collects in tiny vials filled with alcohol.

Finished collecting for the day, he stowed his equipment in his car, and squinted into one of those vials, trying to identify the tick specimen. “It’s probably a lone star because the alcohol didn’t kill it right away,” he said. “They’re tough.”

UPDATE: A previous version of this story incorrectly referred to ticks as insects. They are arachnids.

Tick populations are reduced through the use of prescribed fire.