By the late 1970s, the odor seemed just about everywhere on the east side of Niagara Falls, New York, in a neighborhood with thousands of residents and two area public schools. Noxious fumes seeped into basements. The stench filled backyards. It clung to one engineer’s sweater for days after his visit. A chemical stain appeared on the bed sheets of one factory worker. The odor was spreading from drums the Hooker Chemical Company had unceremoniously dumped decades prior in an unfinished canal.

That canal was built by a shady developer who — in journalist Keith O’Brien’s telling — had skipped town by 1896. His name was William Love. The neighborhood built atop the toxic landfill would become a household name, cultural shorthand for catastrophe: Love Canal.

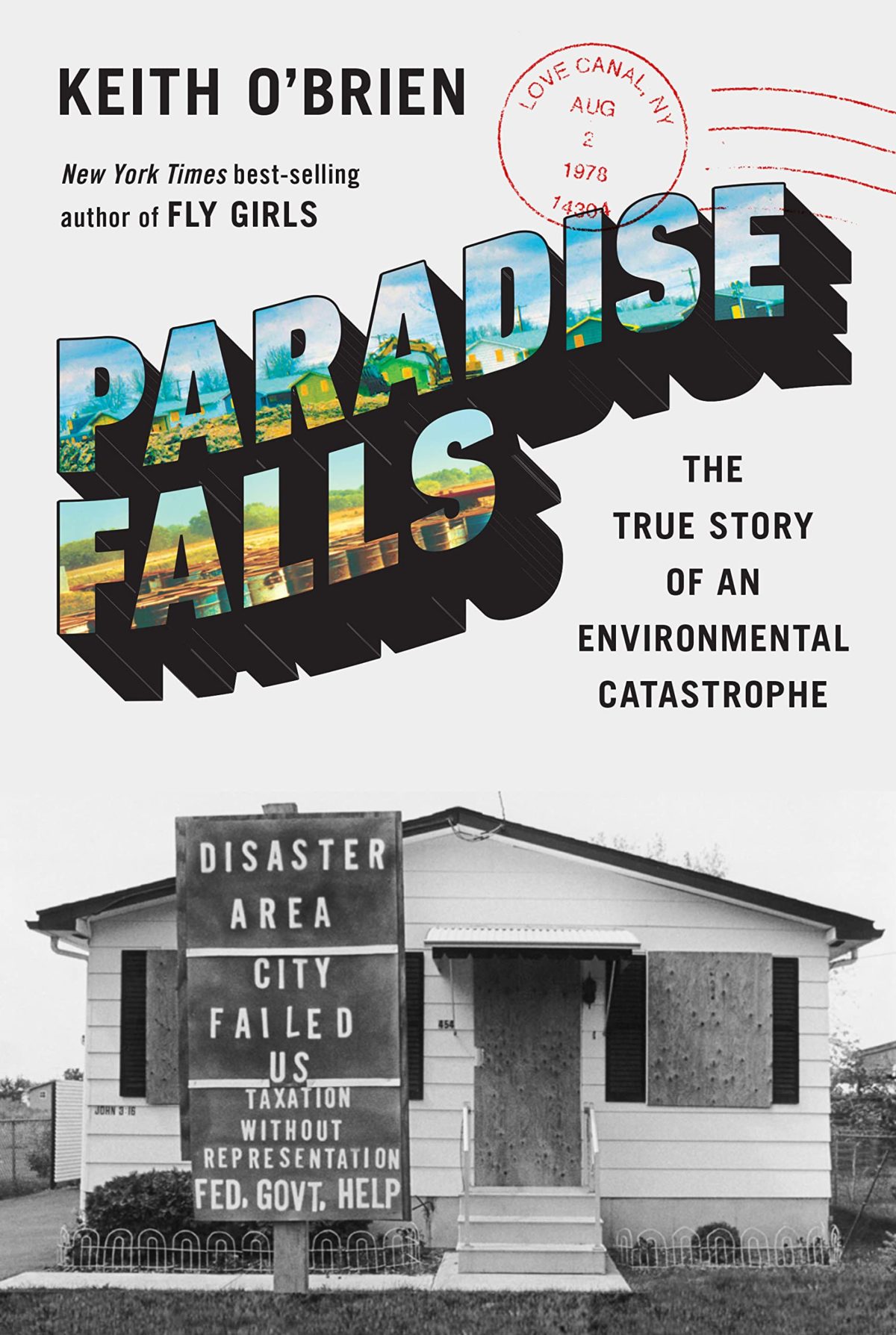

BOOK REVIEW — “Paradise Falls: The True Story of an Environmental Catastrophe,” by Keith O’Brien (Pantheon, 480 pages).

O’Brien’s book “Paradise Falls: The True Story of an Environmental Catastrophe” begins in the 1970s, as children unearthed rocks that made their eyes burn. “Secrets,” O’Brien writes, “long kept in Niagara Falls, began bubbling to the surface on the east side of town, seeping into people’s homes, newspaper stories, national headlines, and finally the American consciousness at large.”

O’Brien, a longtime contributor to National Public Radio, focuses on the women who put Love Canal on the map — and on the national news. Chief among them: Lois Gibbs and Luella Kenny, two mothers whose efforts to leave their neighborhood were galvanized by fears, ultimately well-founded, that toxins were seeping into their children’s bodies and doing harm.

Gibbs started by knocking on doors, organizing a homeowners’ association, as “a loose, somewhat disorganized, and increasingly contentious group of people who really had only one thing in common: they had made the unfortunate decision to buy an affordable home on the cusp of the old Hooker landfill.” The two crossed paths after Kenny’s son unexpectedly became sick and died. O’Brien has a penchant for unlikely duos: Gibbs is described as a 20-something smoker who “barely graduated from high school” and didn’t attend church; Kenny, in her 40s, worked as a scientist, had her kids attend Catholic school, and “never touched cigarettes.”

Kenny, who was initially wary of being a public figure, searched for links between chemical exposure and her son’s problems. She and her husband copied scientific journals in the library, which is not exactly heart-pumping reading. But O’Brien does his best to play up the drama. The blue light of the photocopier flashes on their faces. “They had compiled a stack of journal articles that would have worried any parent, and they knew what they needed to do next,” he writes. “They needed to start speaking out, Luella said. Go public. Talk to the reporters who kept calling. Something.”

“Paradise Falls” retreads some familiar turf. Gibbs’s story, quite literally, became a 1982 made-for-TV movie, and O’Brien describes her as “America’s most famous citizen activist.” O’Brien draws in a wider cast, including hidden figures who played key supporting roles, like Bonnie Casper, a congressional aide, who pressed her colleagues on the issue, and Maria Crea, the doctor who first correctly diagnosed Kenny’s son. He spends a significant amount of time with Beverly Paigen, a scientist who helped the local residents collect data and presented officials with alarming results showing elevated rates of miscarriages and birth defects around Love Canal. (O’Brien casts Paigen and her husband as another unlikely pair.)

Paigen faced potential retaliation, but, O’Brien writes, “She was willing to sacrifice her career for Love Canal, and for what she believed was right.” The book also includes Elene Thornton, a single Black mother, who advocated for the low-income tenants of her housing development, hinting at the tension within a movement that had spotlighted White homeowners.

Hundreds of citizens rallied in the streets. Activists faced down corporate suits at Occidental Petroleum, the parent company of Hooker Chemical. Residents deal with bumbling bureaucrats and politicians, and eventually convince what O’Brien calls “a veritable wall of state scientists and medical doctors.” The action sometimes unfolds in a kind of “Forrest Gump” fashion, where characters bump elbows with major figures in recent American history: Jimmy Carter (who, in O’Brien’s retelling, makes for another unlikely duo with then-New York governor Hugh Carey), Mario Cuomo, Al Gore Jr., and Jane Fonda are among the politicians and celebrities making brief appearances.

The narrative has refreshingly little exposition. O’Brien occasionally weaves historical reference points, such as the publication of “Silent Spring,” Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking book, but the story follows characters chronologically over the span of nearly four years. Gibbs called her neighbors to systematically collect data. With Paigen’s help, they analyzed and presented what one scientist derisively deemed “useless housewife data.” The results went public. The action all came to a head when Gibbs and other community activists held hostage two Environmental Protection Agency employees (yet another “odd couple,” according to O’Brien). Around that same time, Kenny flew to California and disrupted the Occidental shareholder meeting.

Their crusade paid off: The federal government announced it would evacuate their neighborhood and pay for the relocation of families. Two years later, the houses of Love Canal would begin to be razed.

O’Brien frames the story as the result of collective action, although the pace sometimes slows as the book’s overstuffed cast of characters grows. Take Michael Brown, a journalist for The Niagara Gazette, who drove a red Mustang and initially broke the story after catching wind of Love Canal at one of the “boring, endless meetings” (as O’Brien puts it) local reporters are forced to endure. Brown subsequently gets hauled before Hooker executives just as he’s about to land a story with The Atlantic. O’Brien leaves it at that — without making it clear the company did not snuff out the story: a quick search of The Atlantic’s archives makes it clear the story ran in 1979. Further along in O’Brien’s tale, Brown resurfaces, one of many threads loosely woven into a human tapestry of exceptional thread count.

Clearly, O’Brien has done a lot of research — in archives, in previously unreleased personnel records, and in confirming first-hand accounts — and he does his best to convey the emotional undertow and sensory details of the hearings and many meetings. When Gibbs first grabbed the microphone in 1978 — an act that marks her turn to activism — there’s a shriek of feedback. Foul odors permeated the auditorium during that raucous meeting. After another grueling night, Gibbs comes home and hungrily scarfs down some dessert, only to realize later that she’s eaten her son’s birthday cake. Ultimately, though, as any local reporter will tell you, there are only so many public meetings one can endure before nodding off.

Eventually, fences go up around the emptied neighborhood. Life goes on. In an epilogue, the author chronicles the long-lasting repercussions. Love Canal undeniably became a landmark in the history of environmental disaster, and “Paradise Falls” testifies to the power of ordinary people who did science and made history — and did so against some stiff political headwinds. The book doesn’t delve too deeply into more recent scholarship highlighting the tensions between environmental racism and environmental justice. In the end, it’s a feel-good tale about the women’s triumph, accomplishing something no one thought possible: they confront the corporate villain, and their activism leads to lasting change.

Their actions led directly to the 1980 Superfund program, which, despite the shortcomings noted in the book, continues to transform industrial sites and landfills and has almost certainly prevented future disasters. “The legislation — sparked by Love Canal, developed by EPA administrators, supported by elected officials across the political spectrum in a lost era of bipartisanship, and signed by Carter in one of his final acts as president — has saved or improved countless American lives.”

Peter Andrey Smith is a freelance reporter. His stories have been featured in Science, STAT, The New York Times, and WNYC Radiolab.