Old Ji is a 40-something delivery driver employed by Meituan, one of China’s biggest online platforms for shopping and retail services. After Wuhan was locked down, Old Ji posted his first Weibo message on Jan. 24, 2020: “#Wuhan novel coronavirus# It’s coming to me closer and closer.”

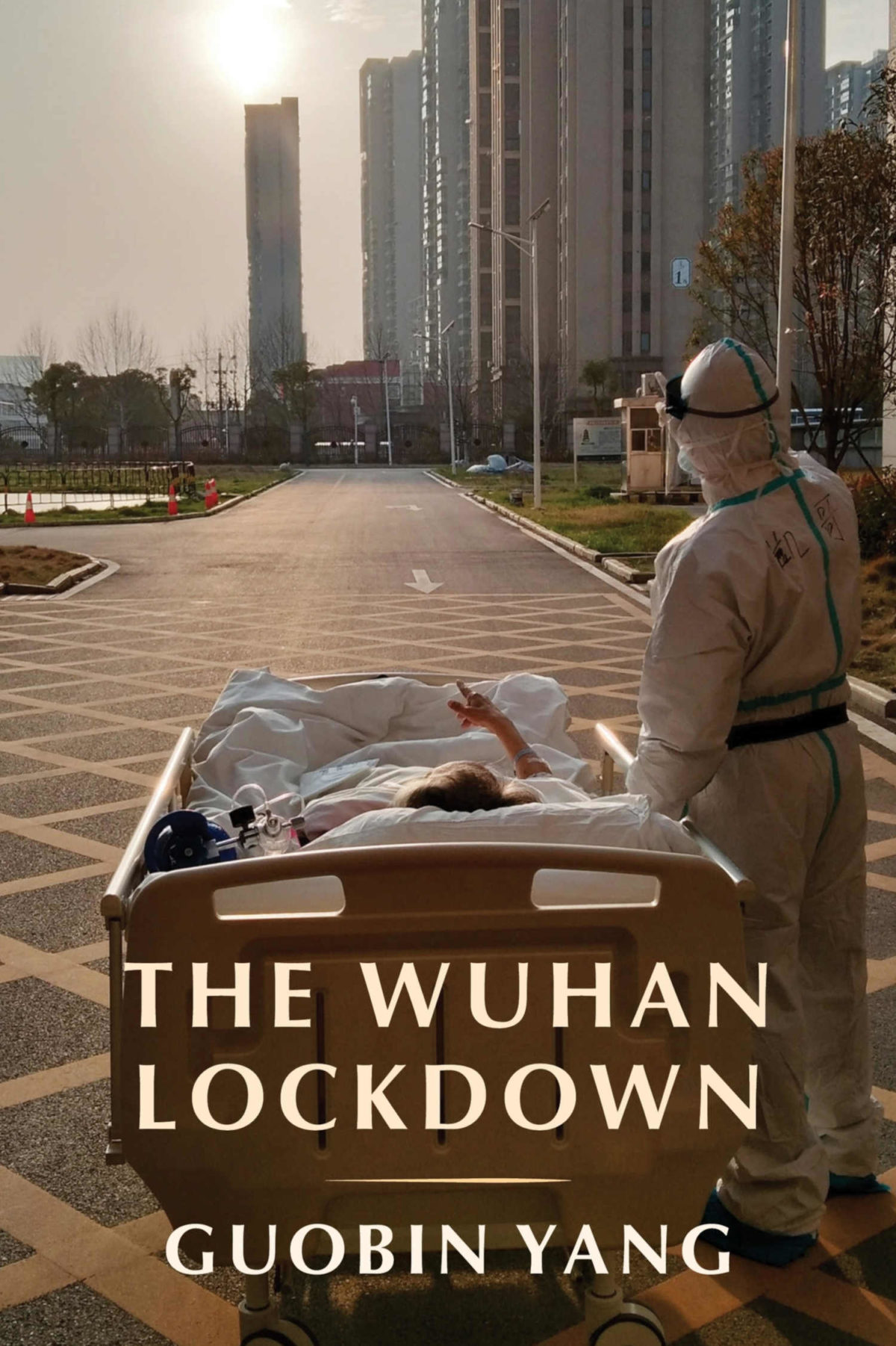

The accompanying article is excerpted and adapted from “The Wuhan Lockdown,” by Guobin Yang (Columbia University Press, 328 pages).

The message was posted with two photos. One photo shows three people in full PPE entering a building in a residential community. The other is of an “urgent notice” issued by the property-management office of his community, notifying residents that a couple had contracted the virus and were under quarantine at home. The notice urged residents not to leave home but if they had to, to wear face masks.

From then to the end of the lockdown, Old Ji put up about 400 posts on Weibo, averaging five a day. Most of them were as short as the one quoted, but there were also longer ones depicting in detail what he was doing on his job and what he saw and felt as he drove around Wuhan making his deliveries. He used various hashtags, such as “chitchat” (xuxu daodao), “guarding Wuhan” (shouhu Wuhan), “seeking help” (qiuzhu), and “Wuhan diary” (Wuhan riji). For him, these Weibo posts were his Wuhan diary.

In another post on Jan. 24, Old Ji forwarded a short video showing health care workers in Wuhan Tongji Hospital having their Lunar New Year’s Eve dinner. For most Chinese families, this is the most important dinner of the year, but the video showed the frontline medical workers eating instant noodles. Old Ji commented: “As a delivery guy (waimai xiaoge) in Wuhan, I feel guilty. I’m so sorry!” And then immediately in his next post, he wrote: “I feel ashamed to see frontline medical workers eating instant noodles on New Year’s Eve! I’m going back to work tomorrow. As much as possible, I’ll take delivery orders to hospitals.”

His first post the next day showed a map of his delivery route: “My first delivery order of the New Year was sent to the Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University.”

The phrases that Old Ji used as hashtags in his posts, shown as English translations and the original Chinese characters.

Thus began Old Ji’s busy life as a delivery man while Wuhan was under lockdown. His Weibo postings documented this life in detail, showing aspects of lockdown life that would otherwise have remained little known. One post on Jan. 26 was a direct quote from a customer: “Mom cooked a meal. Please deliver it to my father. My father is a frontline physician. Thank you, delivery brother!” And then another post:

“(Be warned about clicking image 6.) When I was about to get off work, I received an order to help a girl who was not in Wuhan to look after her cats at home. She has been away from Wuhan for four days. And…when I entered the room, my glasses were foggy and I didn’t see clearly. I thought there were dead mice on the floor. And … and … they turned out to be dead kittens. [Crying emoji here.] One of her cats gave birth while she was away. The owner of the cats was on WeChat with me. She was choked with sobs. What the fuck can I do? Sigh.”

In later posts, Old Ji would share other stories about cats, including taking an order to find a missing cat and ending up chasing the cat on the rooftop of a high-rise building.

Old Ji drove around town on a battery-operated moped. More than once, while he was making deliveries, his moped battery died, and he got stuck. This happened on Jan. 27:

“I didn’t calculate the battery power properly. My moped broke down! Before the breakdown, I took a supermarket purchase order and delivered a big bag and a small bag of snacks. But the small bag was stolen! We’re still observing the New Year and this happened? I hope the small bag of snacks was taken by someone who really needed it. If you ate it out of hunger, I would be happy. But please be merciful toward us delivery drivers! This is a time of hardship. We are in the same boat! (Although this makes me feel much better, I still have 3 kilometers to walk my moped. Who knows how I feel?)”

On Feb. 7, the day Li Wenliang died, Old Ji received a mysterious order: “Please deliver a bouquet of flowers to the venue for mourning Dr. Li Wenliang.” And so he did. After putting his flowers amid a mountain of flowers already there, he bowed in front of Li’s picture and then left.

Although Old Ji did complain about the hardships of his job from time to time, he generally came across as a strong and optimistic person in his diary posts. When he decided to get back to work on Lunar New Year’s Day, it was because he was moved by the dedication and sacrifice of health care workers and he wanted to help out by delivering goods and services to people in need. His Weibo postings of his delivery experiences documented his daily struggles as well as those of other Wuhan residents.

As in other countries, however, delivery workers in China have a precarious existence. Because they work for corporations that use apps to run their businesses, they are at the mercy of algorithms. In September 2020, the popular magazine Renwu published a long-form investigative report about delivery workers that drew national attention to their dire conditions. The story found, for example, that delivery workers are involved in a disproportionately high number of traffic accidents, hitting others or being hit, because they are forced to drive at high speeds to meet their delivery deadlines. The algorithms of the delivery apps calculate the fastest route for each delivery and give them the shortest possible time to make it. Delivery workers are, as the title of the story goes, “stuck in algorithms.”

And yet, stuck as they were in the algorithms, delivery workers rose to the occasion of the lockdown to offer their services to a city in need. As Old Ji’s story shows, he was moved to action by the personal sacrifices made by the health care workers. And he endured hardships as he made his delivery rounds. How was this possible? What should we make of Old Ji’s story? Answers to these questions may be gleaned from the wealth of online diaries produced during the lockdown.

After the city of Wuhan was shut down, many residents started writing “lockdown diaries,” which they shared on social media. These early diaries presumably inspired others to write, and within weeks there was an explosion of online lockdown diaries. Most of them ended when the lockdown was lifted on April 8, but some continued.

Their authors represent a broad spectrum of the Chinese urban population. There are more women than men among the diarists: 28 (61 percent) of the 46 diarists cited in this book are women. They have diverse professions, however, and include high school teachers, graduate students, university professors, poets, novelists, retired teachers, lawyers, frontline health care workers, government officials, feminist activists, social workers, professionals in media industries, a Christian, and a delivery driver.

Two diaries were produced by Covid patients. Given the diverse authorship, the contents of the diaries are also wide ranging. Some are rich with descriptions of daily life and personal feelings. Others are sparse in personal details, focusing instead on news of the day. On the ideological spectrum, there are diaries by liberal authors such as Fang Fang, the poet Xiao Yin, and the feminist activist Guo Jing, but a few diaries have strong nationalistic tones.

Most fall somewhere in between, with relatively few ideological intonations. Fang Fang’s diary is the best known, but there are many other valuable and informative diaries. About a dozen diaries have been published since the end of the Wuhan lockdown.

As the Covid-19 pandemic spread globally, lockdown diaries appeared in other countries, but their volume is far smaller than the diaries that came out of Wuhan. Why did they thrive in China? Because no other city in the world experienced a lockdown quite like the one in Wuhan.

Cities in other countries hit by the pandemic may have suffered far more casualties, but Wuhan experienced the first shock. Wuhan residents knew nothing about the pandemic when it first broke out. They were taken by surprise. And when it did dawn upon them that a SARS-like disease had broken out, they immediately recalled the horrible scenes of the SARS crisis in 2003.

|

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive. |

The abrupt lockdown of a city as gigantic as Wuhan drove home the gravity of the situation. Even before any stay-at-home orders were issued, residents voluntarily confined themselves to home. And the city’s lockdown was the most drastic of its kind. No other city in China or the world was sealed off as abruptly, decisively, and tightly as Wuhan.

The lockdown suspended all outbound and inbound traffic — air, railway, highway, waterway. Traffic within the city was highly controlled. Starting on February 10, a system called “closed management” was strictly enforced in Wuhan. It closed down all residential communities, and only essential workers were allowed in or out.

It was under these conditions that so many lockdown diaries appeared online and attracted so many readers. The boom of lockdown diaries in Wuhan reflects an acute public awareness of the seriousness of the health crisis and a desire to document an unprecedented historical event.

Guobin Yang is the Grace Lee Boggs Professor of Communication and Sociology at the Annenberg School for Communication and the Department of Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, where he directs the Center on Digital Culture and Society and serves as deputy director of the Center for the Study of Contemporary China.