The ancients had a surefire way to cut through the fear and unpredictability of an epidemic: A quick visit to an oracle would reveal the nature and course of the disease, and even the cure. After the afflicted citizens followed instructions to sacrifice a youth, recover some old bones, fashion some hemorrhoid-shaped statues out of gold, or whatever else the priests recommended, the plague would be lifted, and life would go back to normal — or so, at least, the thinking went.

Modern-day humans look to scientists rather than sibyls to answer questions about the natural world. But this means that we have to sacrifice the speed and certainty of oracles for the slow, uncertain bumbling of scientific progress. This is the one sacrifice that science requires us to make, and it’s what gives scientists their power to understand the natural world in a way that oracles and priests never could. Yet, during the coronavirus crisis, it seems to be hurting us in ways we never expected.

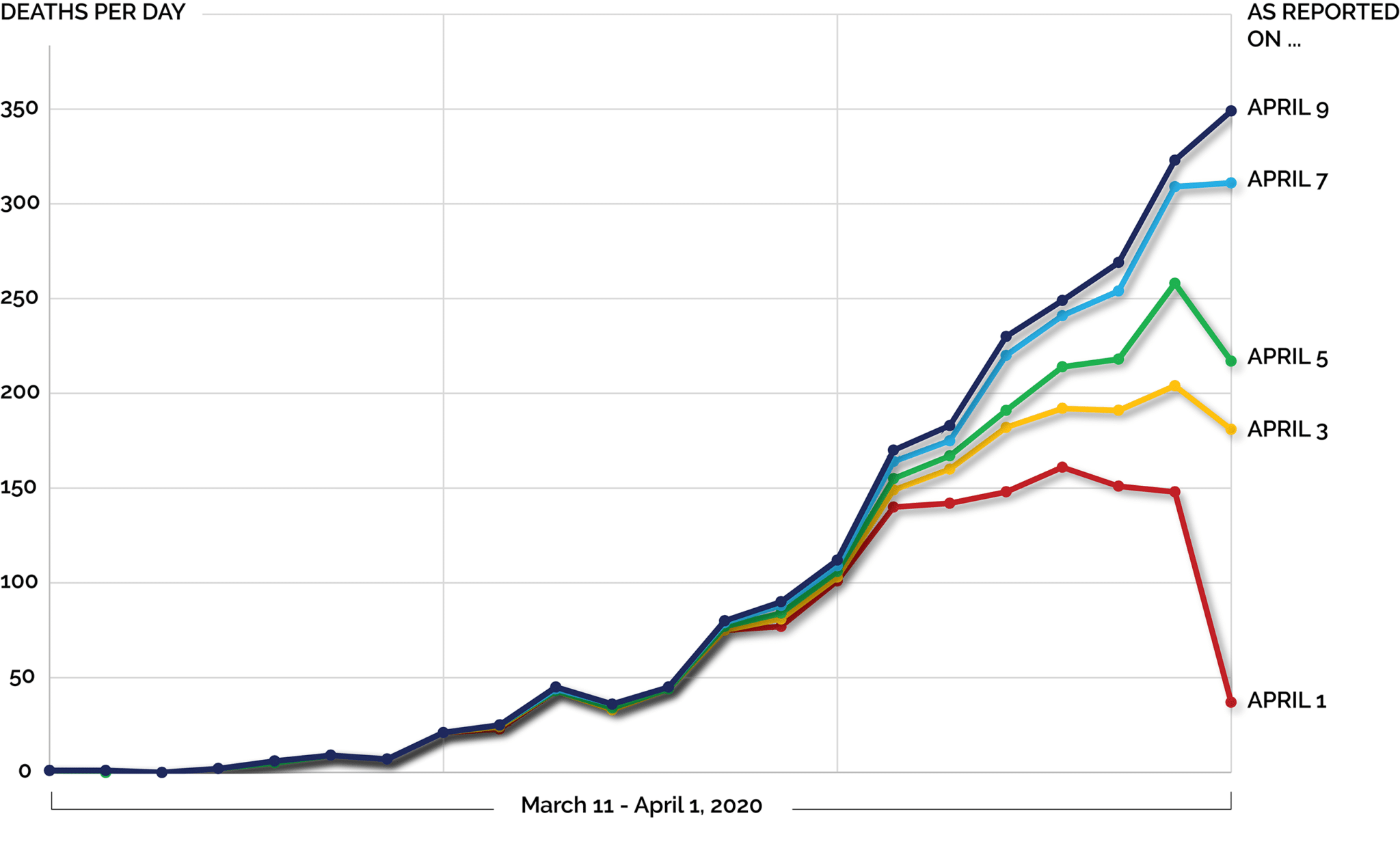

One of the most pernicious ways has to do with the time it takes to tabulate deaths due to Covid-19, especially in jurisdictions where hospitals are overworked. In New York City, for example, some deaths are reported to the city’s health department within hours, but others take days — sometimes a week or more — to get tabulated. This delay means that on any given date, when officials announce the daily death toll, they do so having received only a fraction of the death reports that will eventually come in.

On the afternoon of April 1, for example, New York City officials declared that 1,374 people had died of the virus to date. But the accounts of deaths kept coming in. Two days later, the tally of people who had died on or before April 1 had climbed to more than 1,700. By April 5 it stood at 1,878. As of April 9, the official count was 2,253, a roughly 60 percent increase over the initial tally. This number will likely continue to rise, slowly, for several more days.

One peculiar consequence of this delay-induced error in the numbers is that it distorts our perception of the progress of the epidemic. The misleadingly low numbers announced each day can make it look like we’re perpetually about to crest the peak of the epidemic — that is, as if the death rate is leveling off — even when the real toll is climbing unabated. It’s a cruel deception: The errors give us hope that the worst is over, though the true peak may remain days or weeks away.

It’s not just the staggered death reports. All the numbers — all the data — about coronavirus are tainted with uncertainty in some way. When news outlets announce, as one did on April 9, that the number of cases of coronavirus have topped 1.6 million, that datum has little relationship to reality. That number merely represents the people who have tested positive for the disease. Not only are the tests error prone (sometimes worryingly so), many people with Covid-19 have yet to be tested for the disease at all.

It’s nigh impossible to correct for those inconsistencies, especially given that testing rates and policies differ radically from place to place and day to day. Scientists can’t yet say with certainty how many people are really infected: It could be five times, 10 times the official number or even more. Even future historians may one day argue about precisely how many people were infected and when, just as they now do about the 1918 flu pandemic.

It’s also inevitable that some deaths due to Covid-19 will be mistakenly attributed to other causes — and vice-versa. Tens of thousands of people die in the U.S. every year from pneumonia or influenza; it’s often difficult to tell if a person’s demise was due to the novel virus, the ordinary flu, or something else entirely. And not everybody who dies from Covid-19 will die in a hospital where his or her death can easily be counted. New York City officials — who have collected some of the most detailed, trusted data on coronavirus mortality in the U.S. — just reported that hundreds of people are thought to be dying of Covid-19 complications at home each day, and those deaths until recently were not being counted in official tallies. Given that the official daily death tolls in NYC are also in the hundreds, this is likely a huge source of error, and the true death toll could be much higher than previously thought.

Make no mistake: Science is unquestionably the best tool we have for trying to understand the Covid-19 pandemic. But this is the best that science can do right now. Someday, looking back at the pandemic, the numbers will be much clearer. The data will all be in, and we’ll be able to more accurately see the outbreak’s contours and its course.

But right now, we’re at the mercy of Nature to produce the information we need — and Nature will not be rushed. It works at its own pace, and its pace is simply not fast enough to give us the certainty and the peace of mind that an oracle would give us. Confronted with one of the most urgent scientific challenges of our time, however, that’s a sacrifice we have to make.

Charles Seife is a professor of journalism at New York University, and the author of numerous books, including “Proofiness: The Dark Arts of Mathematical Deception.”