There are two stories that people tell about Onesimus, the enslaved African who helped save hundreds of Bostonians from smallpox in 1721.

The first is a simple one. When Onesimus is asked by his owner, Cotton Mather, about a scar on his forearm, he proceeds to describe the basics of smallpox inoculation — a practice that was already common in Asia and Africa but still relatively unknown in the American colonies. Onesimus explains that when the pus from an infected individual’s pustules is inserted into the broken skin of an uninfected person, the person suffers a mild reaction, but becomes immune to future infection. In the words of Onesimus, as transcribed by Mather some years later, “People take Juice of the Small-Pox; and Cutty-skin, and Putt in a Drop.”

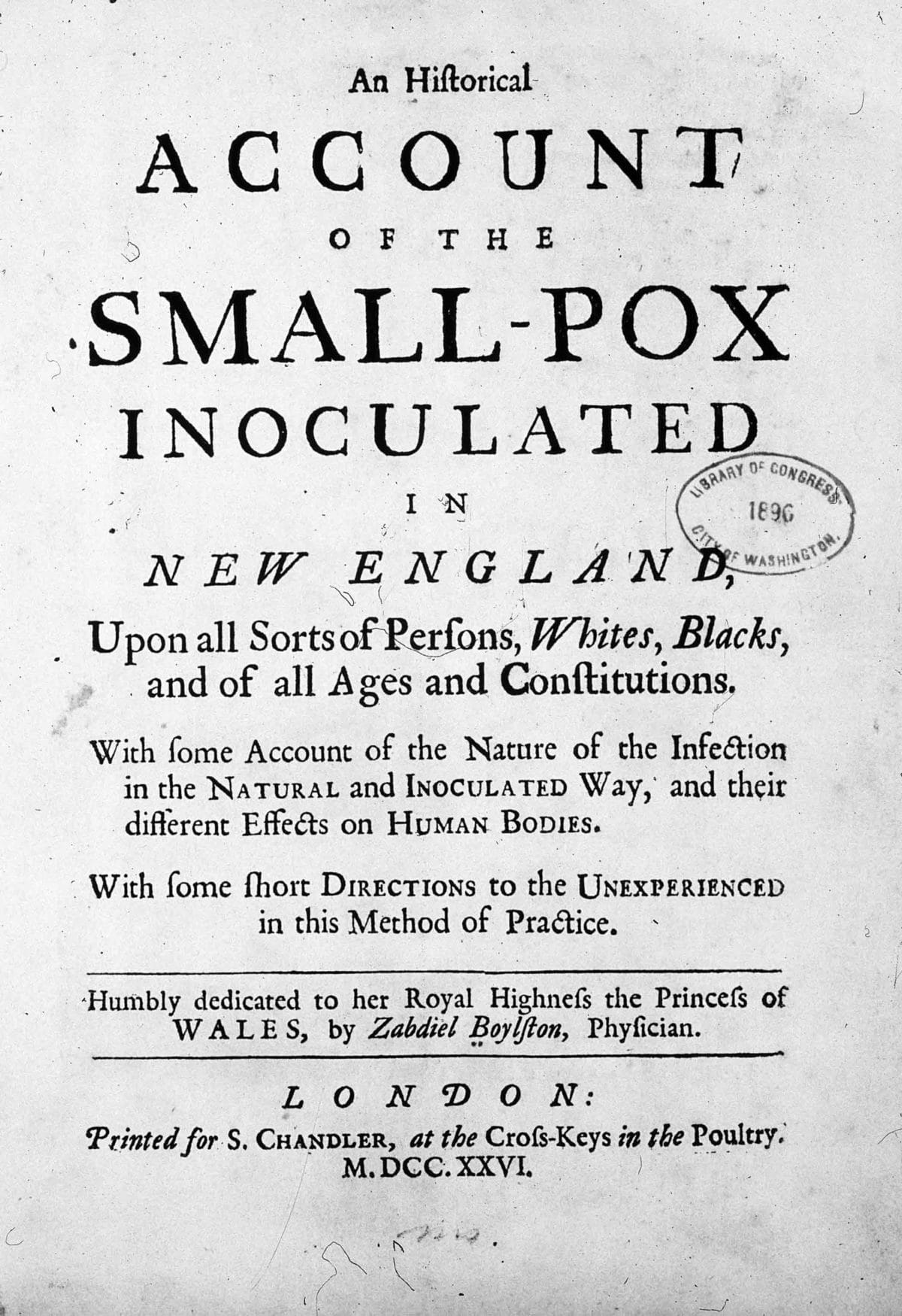

In this version of the story, when a British ship arrives from Barbados overrun with smallpox in 1721, triggering the worst epidemic Boston has ever seen, Mather shares the slave’s suggestion with another white man, physician Zabdiel Boylston, who bravely attempts the procedure on his son, and then on other patients. Inoculation saves hundreds of lives, and the two men go down in history as the lifesaving duo that brought inoculation to the American colonies.

As a Boston-based medical student with an affinity for black history, I’m troubled by this telling of Onesimus’ story. Like so many of the historical narratives we’ve become accustomed to in American culture, it is dominated by whiteness, and it erases the contributions of black people. It paints Mather and Boylston as heroes and relegates Onesimus to their shadows.

This erasure of black and African contributions to medicine is frustratingly common in American culture. A casual learner might never know the cure for scurvy originated from African orange traders or that Vivien Thomas, a black man, created the first surgical procedure to cure blue baby syndrome. When we are mentioned, black people are often portrayed as unknowing participants or victims of scientific experimentation.

Thankfully, there is a second, more authentic story that scholars and some journalists are beginning to tell about Onesimus. The biographical details are the same, but the context is richer.

This second version of the story does not gloss over the indefensible fact that Mather, a Puritan minister, treated Onesimus as his property. In 1706, Onesimus was kidnapped from his homeland in North Africa, sold into slavery, and then purchased and gifted to Mather by his congregation. In this telling of the story, Mather, an influential supporter of the Salem Witch Trials, is conflicted about trusting a slave. Although he admires Onesimus’ intelligence, he is wary of the “devilish rites” of Africans and writes in his diary about the need to watch Onesimus closely due to his “thievish” and “wicked” behavior. After Onesimus shares with his owner the knowledge that will save hundreds of lives, the slave must still wait years to save up the money to buy his own freedom.

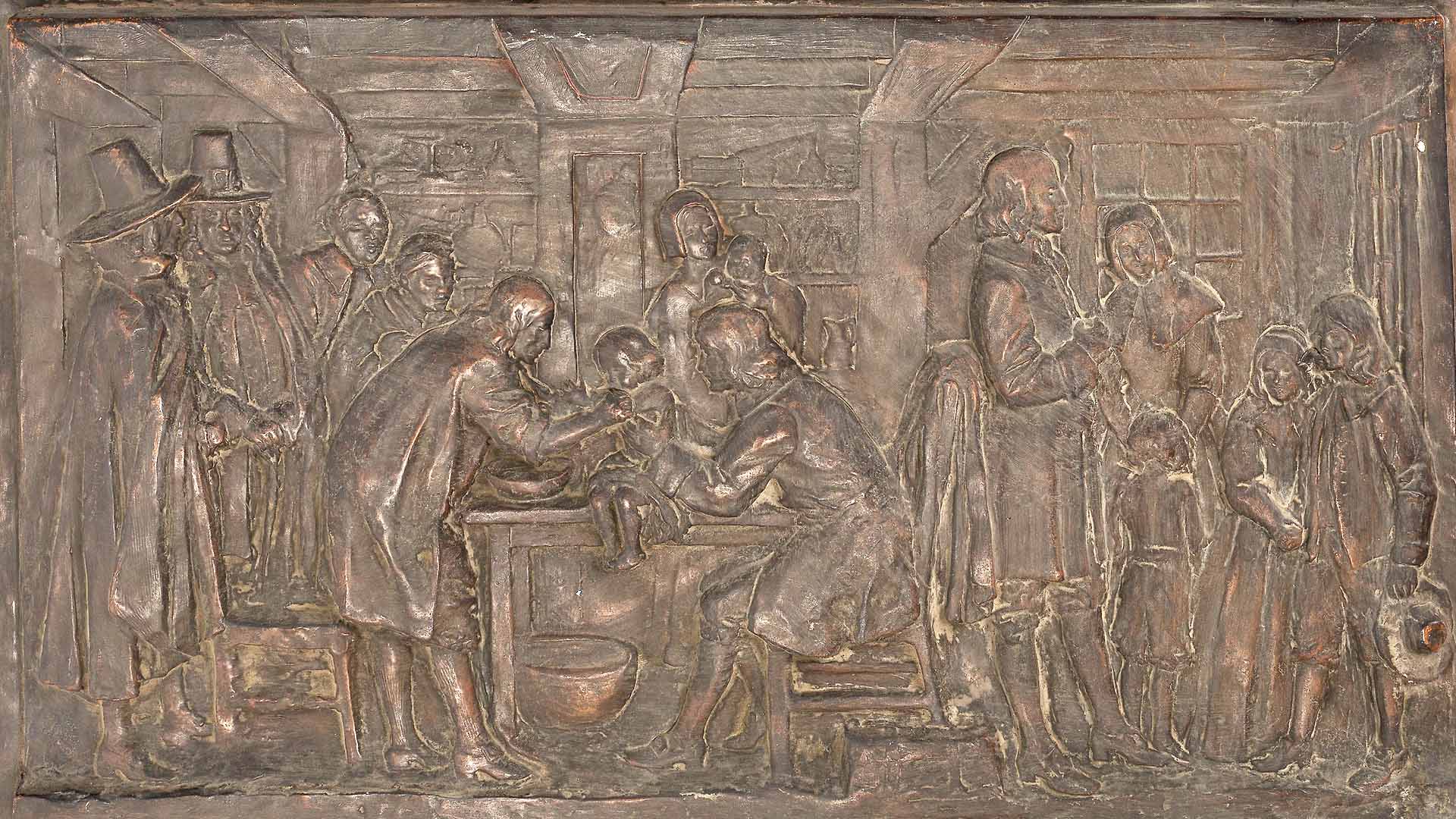

This second story acknowledges the murky ethics of inoculation’s rollout in the colonies. It reminds us that, in addition to inoculating his son, Zabdiel Boylston tested the procedure on his two slaves — a brand of exploitation that crops up time and time again throughout the history of medicine. From the advent of modern-day gynecology to the Tuskegee syphilis study, black people have been the guinea pigs behind some of our country’s biggest medical and public health experiments.

Even after they demonstrated the efficacy of inoculation, Mather and Boylston encountered violent, racist pushback when they attempted to introduce the technique to the Boston medical community. Many doctors could not fathom the idea of a long-awaited preventive treatment coming from Africans. Only when they were left with no choice — when they were confronted with the deadliest smallpox outbreak in Boston history — did they resort to Onesimus’ technique.

“An Historical Account of the Smallpox Inoculated in New England,” written by Zabdiel Boylston

Visual: MPI/Getty Images

Ultimately, inoculation proved its effectiveness to the medical community in Boston and beyond. The 1721 smallpox epidemic killed 844 people and sickened 8,000. But only one in every 48 inoculated patients succumbed to the disease, compared with one in nine untreated patients. The procedure eventually led to Edward Jenner’s discovery of vaccination, which has spared millions of lives from disease.

Onesimus, however, was all but erased from this story of medical triumph. On June 9, 1932, prominent psychiatrist and medical leader, Dr. Samuel Bayard Woodward addressed the Massachusetts Medical Society to tell the story of smallpox in Massachusetts; Onesimus was only mentioned once. Unfortunately, this facelessness has become the norm for black contributors to science and medicine.

As a student at Harvard Medical School, I am reminded of this facelessness nearly every day, when I stroll through Harvard Medical School hallways adorned by opulent golden-framed portraits of white men. These subtle fixtures are reminders that our decisions to celebrate certain historical figures are influenced by the privilege that comes with agency and access. The reason we do not see more portraits of people of color is not because they are not worthy, but because their contributions so often lie silently behind the monoliths of white men.

There are signs that Onesimus is beginning to get his due. He was mentioned in Boston Magazine as one of the “100 Best Bostonians of All Time”. The Boston Globe and History have each attempted to bring his story to light. Still, what little acclaim Onesimus has received pales in comparison to the plaudits heaped upon his two white counterparts.

Racism and systemic injustice have historically made it impossible for individuals like Onesimus to be acknowledged as the key contributors to science that they truly were. It is up to us to reevaluate the stories behind science’s greatest accomplishments and find the hidden luminaries who deserve a place in history.

LaShyra Nolen is a first-year student at Harvard Medical School.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I like a true story that’s far RICHER. But, I like no details left out. Who kidnapped Onesimus from North Africa?

The search for life on other planets is another lie whiteness has propagated. In keeping my comments brief I suggest studying the history of the “discovery “ of the star Serius then follow that up with study of the “mythology” of the Dogon people of West Africa.

Another glaring one is: mathematics ascribed to the Greeks while the evidence of the pinnacle of mathematics resides in Africa in the form of the great pyramids.

This is from Wikipedia.

Onesimus (late 1600s–1700s[1]) was an African-born man who helped mitigate the impact of a smallpox outbreak in Boston. Enslaved and given to Puritan minister Cotton Mather beginning in 1706, he introduced Mather to the principle and procedure of inoculation. After a smallpox outbreak began in Boston in 1721, Mather used this knowledge to advocate for inoculation in the population, a practice which eventually spread to other colonies. In a 2016 Boston Magazine survey, Onesimus was declared one of the “Best Bostonians of All Time”.[1

It doesn’t say a word about Mather taking all the credit. MS Nolen it looks as though you only looked at half of the story…the activist half.

I guess you are only interested in Activism and not common sense.

If what you say is true MS Nolen, Activist and writer…the doctors at the time had two choices. Tell the story as you say it is and risk the backlash or save lives. Thankfully they chose the latter.

There are a lot of discoveries made in science medicaments astronomy by Muslim scholars but the credit is taken by the White man they change the names in some cases to sound like a white man’s name.

But they forget what goes around comes around.

There are a lot of discoveries made in science medicaments astronomy by Muslim scooped but the credit is taken by the White man they change the names in some cases to sound like a white man’s name.

But they forget what goes around comes around.

Dear La Shayra:

Enjoy immensely your recount of the history of Onesimus as a reminder of the societal discrimination against people of color that continues to occur. Your eloquence and boldness as a first year student at HMS is evident and we are all proud of your contributions and hope that our school will recognize them.

Ernesto Gonzalez-Martinez, M.D.

Professor of Dermatology

Harvard Medical School