When Residents Say ‘No’ to Aerial Mosquito Spraying

On a Friday afternoon in late September, Kalamazoo County Health Officer Jim Rutherford announced that aircraft would mist much of the county with an insecticidal spray. Intended to kill mosquitoes, the emergency plan quickly turned into a public relations battle. Hundreds of calls and emails — and even some threats — streamed into Rutherford’s office in southwest Michigan, many expressing concern about the spray.

In the United States, an average of seven human cases of eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) are reported annually, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But 2019 has been an especially bad year for the mosquito-borne virus, with at least 35 cases and 13 deaths reported nationwide. In Kalamazoo County, when Rutherford made his decision, EEE had killed a 64-year-old man and sent a 14-year-old girl into intensive care. Faced with the prospect of several more weeks of mosquito-friendly weather, Michigan state officials had offered 15 counties the option of spraying. All of them accepted.

“This technology is fully recognized as a public health intervention for mosquito-borne diseases,” Rutherford said, citing information from the Environmental Protection Agency and the CDC. But that didn’t stop thousands of residents from flooding the state’s pesticide opt-out system, requesting that their properties be exempted from spraying. Rutherford said he repeatedly heard things like “the government told me Roundup was safe forever, the government told soldiers that Agent Orange was safe forever” — only to later be informed of previously unforeseen risks.

Three days after the initial announcement, Kalamazoo County called off the spray. More than 1,400 residents had exercised their right to opt out, creating a patchwork of no-go zones that simply made aerial spraying unworkable. Spraying did occur in the other 14 counties, skirting the property of around 1,600 additional opt-outs, and over the vigorous objections of many residents.

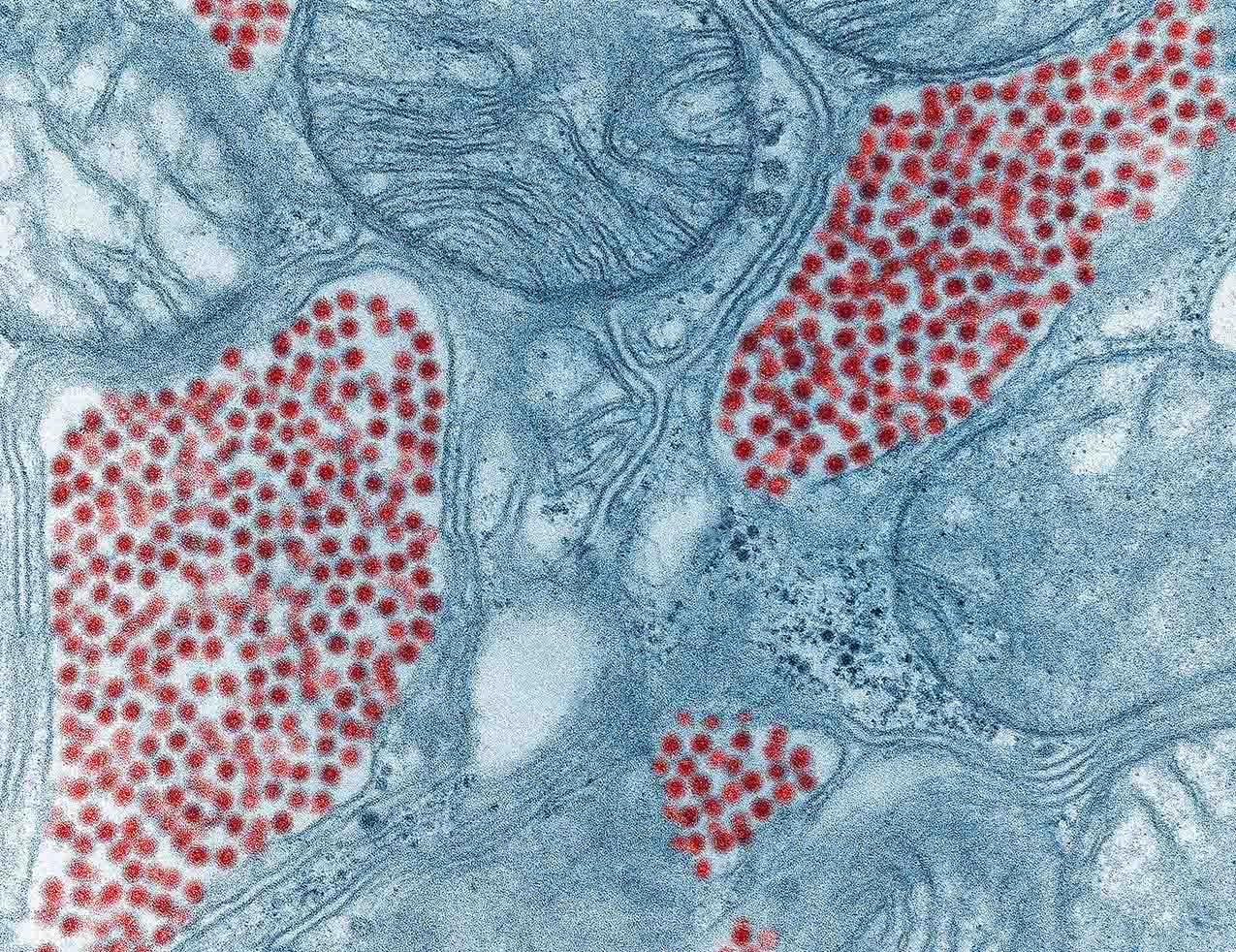

A female cattail mosquito, Coquillettidia perturbans, taking a blood meal. In Michigan, this species is an important bridge vector for the EEE virus, transmitting the virus between species like birds and humans.

Visual: Sean McCann, Department of Biology, Simon Fraser University

A hard frost will soon kill this year’s remaining adult mosquitoes in Michigan, Massachusetts, Indiana, and other affected states. But as a warming climate promises to increase mosquito-borne disease outbreaks across the northern United States, including EEE, the controversy raises questions that may resonate for years to come. When should elected or appointed officials compel people to accept public health interventions? When should people have the chance to opt-out? And, in the face of new public health threats, how can communities have constructive, inclusive conversations about risk?

Finding satisfying solutions might not be easy. “There’s not a broad level of trust with government telling people that [this pesticide is] safe,” Rutherford acknowledged. “I get that part of it.”

In a typical year, the adult mosquitoes that spread EEE would be dying out in Michigan by late August. This year, though, they persisted well into the fall — and by September, facing mounting cases of EEE, public health officials grew alarmed.

“At the point where we first started to do the aerial treatments, we had seen more cases in one year than we had seen in an entire decade combined,” said Lynn Sutfin, a spokesperson for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, describing the outbreak as “a public health emergency.”

The state decided to spray Merus 3.0, an insecticide that contains a mixture of plant-derived chemicals, collectively called pyrethrins, that is approved for use on organic farms. Contact with a single, microscopic pyrethrin droplet can kill an adult mosquito. The aircraft often distribute less than an ounce of the chemical per acre — roughly the equivalent of misting a shot glass full of whiskey over a football field, according to Ary Faraji, an entomologist and president elect of the nonprofit American Mosquito Control Association. By contrast, farmers will sometimes use an order of magnitude more per acre when treating crops for pests.

“The overwhelming scientific evidence suggests that these treatments are effective in what they’re designed to do, which is lessen the disease risk, and also that they do not pose significant risks to people,” said Robert Peterson, an entomologist at Montana State University who studies the risks and impacts of pesticide application.

Critics, of course, point to evidence that pyrethrins are highly toxic to honeybees and wild pollinators. But even here, officials and mosquito control experts say that spraying in the evening, when mosquitos are active but bees are not, dramatically reduces the risk to pollinators. Still, that did not reassure some worried beekeepers. The Michigan Pollinators Initiative is currently surveying beekeepers in counties that received aerial spraying, to see if they noticed any difference in their bees.

“No pesticide is inherently safe,” said Drew Toher, community resource and policy director for Beyond Pesticides, a Washington, D.C.-based anti-pesticide advocacy group. “There should be that message out there, that the disease itself is a risk to public health, but so is the use of this pesticide,” Toher said. He cited peer-reviewed research that suggests a correlation between pyrethrin exposure and developmental problems in children. (The studies do not necessarily reflect the exposure levels seen in mosquito spraying). The final decision about how to balance competing risks, said Toher, “should be in the hands of the community.”

That actual decision-making process varies from place to place. During spraying, many places permit opt-outs only for organic farmers, beekeepers, and people with certain health conditions.

In Massachusetts, the site of another significant EEE outbreak this year, once state officials declare a public health emergency, only “certified organic farms, commercial fish hatcheries/aquaculture, priority habitats for endangered species, and surface drinking water supplies,” can be exempted from spraying, according to Katie Gronendyke, a spokesperson for the state’s Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs.

In Elkhart County, Indiana, just across the border from Michigan, elected county commissioners made the decision to spray, only organic farmers could opt out.

The story in Michigan, though, is more complex. Appointed public health officials, at the state and county level, made the decisions to spray, albeit in consultation with elected representatives. And because the state health department, in the interest of time, chose not to seek an emergency declaration from the governor that could override the opt-out, state agriculture regulations permitted individuals to exempt themselves from spraying.

To some people, that opt-out policy may have gone too far. Rutherford, the Kalamazoo County health officer, pointed out that while 1,400 county residents opted out, tens of thousands more did not. “The frustrating part on our end was the fact that 4.5 percent of the population made the decision for the other 95 percent of the population,” Rutherford said.

“The governor could have made this a lot easier had she declared a state emergency, but that wasn’t going happen,” he added.

Elsewhere, supporters of the spraying accused opponents of peddling bad science and obstructing the response to a public emergency. One widely circulated op-ed, published at MLive.com and printed in one of the media group’s papers, The Kalamazoo Gazette, compared the people opting out to individuals who opt-out of vaccines. “Those who have opted out put others at unnecessary risk,” wrote the author, Parker Crutchfield, a medical ethicist at the Western Michigan University medical school.

In an interview with Undark, Crutchfield said he disagreed with the opt-out policy. “I don’t think there should be much choice, frankly,” he said, adding that there should be carve-outs for people with certain medical conditions.

For others in Michigan, the option to avoid spraying did not go far enough. In early October, around 45 people gathered for a special meeting in Webster Township, a community of some 7,000 people about 10 miles northwest of Ann Arbor. Aerial spraying was anticipated in the next few days.

County officials had announced the decision to spray barely 48 hours before the treatments could have begun (they ended up happening later, due to weather), leading to perceptions that the opt-out process was mostly a fiction.

“We value working with our community and hearing from our community and using cooperative decision-making whenever possible,” said Susan Ringler-Cerniglia, a spokesperson for the Washtenaw County Health Department, in an interview with Undark. “But in this situation, this was really a tall order,” she said, emphasizing that officials had been handed a very short timeline because of the public health emergency. She added that effective community outreach had grown more difficult since the scaling-back of the local newspaper.

One speaker at the meeting was Katherine Larson, who lives just outside the spray zone. When we spoke by phone a few days after the meeting, the spraying had finally happened. Larson told me that, prior to the spraying, she had distributed leaflets to residents in the spray zone. The majority of people she talked with, she said, had no idea the spray was coming. When the plane arrived, many residents called her, confused and upset.

“We’re supposed to be free, and we’re still supposed to be able to choose between whether we want to put on pesticides on our skin or repellants on our skin, or whether we want to be sprayed,” Larson said.

“What I care about is people having a choice,” she added. “When your government imposes something on you and says, ‘you have an opportunity to opt out,’ but they don’t give you the time to opt out, then it’s not a choice.”

Where Larson sees an infringement on personal liberties, Crutchfield, the medical ethicist, sees a necessary sacrifice for the sake of community safety. After all, the mosquito flying over my yard today may bite you tomorrow. “We have to allow some sort of intrusion in order to even live as a society,” he said. “And I view the mosquito spraying as one of those minor intrusions.”

One reason for the scale of backlash in Michigan may simply be the novelty of the spraying. Unlike places like Florida, where mosquito-borne sicknesses are recurring threats and aerial spraying is common, if sometimes controversial, Michigan had not sprayed for mosquitos since an EEE outbreak in 1980.

As the climate warms, and northern states potentially deal with more frequent outbreaks of things like EEE, those applications could continue to trigger concern. In an email, risk communication expert Peter Sandman pointed out that spraying for EEE fits two familiar patterns that he sees in other debates. He wrote that, again and again, “natural risks provoke less outrage (concern, fear, anger) than industrial risks.” In other words, something like EEE — a natural risk — may seem less frightening to people than the perceived risks of pesticides. And, Sandman added, “it’s also worth noting that a risky action” — like spraying a chemical — “tends to arouse more outrage than a risky inaction” like standing by while mosquitos spread a deadly virus.

That’s not to say that opponents of the spraying should be dismissed, Sandman said. “I think in many cases public health agencies are overstating the risk of EEE and understating the risk of spraying,” Sandman wrote. “They tell stories about EEE victims without stressing how few such victims they are; they stress the rarity of insecticide poisoning without telling comparable stories about how horrible it can be.” And both risks, Sandman stressed, are relatively small.

All of these conversations will unfold during a time of increasing mistrust in public institutions. Distrust in public health agencies — and in state government more broadly — may be especially acute in Michigan following the Flint water crisis, where government officials wrongly assured the public that Flint’s drinking water was safe. More recently, residents have rebuked state officials for their handling of PFAS contamination in drinking water. (Rutherford noted that Kalamazoo County recently had to shut down a water system because of PFAS contamination.)

For now, the county is left urging people to exercise caution, distributing strong insect repellant to vulnerable populations, and waiting for the first hard frost.

UPDATE: Due to an editing error, a caption in an earlier version of this story misspelled the Latin species name for the cattail mosquito. The story has been updated to correct this error.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

They Could have used Zapout Mosquito lantern Instead

“…a necessary sacrifice for the sake of community safety.” A dangerous trend in America is that the medical/political community are touting this “shared risk for the sake of the majority” narrative. Majority should never trample the individual in America. ANYone can say/has said throughout history that what they’re doing is for the good of the majority, passing draconian laws that trampled a minority. My rights don’t trump yours, if there are a thousand of me and one of you. Your rights don’t trump mine, even if there are a hundred thousand of you and one of me. That’s liberty. If one is allergic to insecticides, if one has an organic backyard garden due to health, if one (justifiably) doesn’t trust the government’s shaky version of science and public health, they should be free to choose for themselves. Declaring a public emergency to pass draconian measures that override the individual is bull. Fear is what they use on the public to get them to override the minority. Fear that their neighbor’s choices will somehow hurt them. Fear tactics should ALWAYS raise a red flag, because that’s the exact method that even put Hitler in power. It’s the oldest trick in the book to shut down and even kill off a minority. Should everyone with an allergy die to keep you safe? How far will you go? What would you do if one day that false fear factor is pointed at you as the culprit? If your neighbor’s liberty falls, yours falls, even if it kept you “safe” for a day.

I live in an area where 2 people died within 1/2 mile of each other. Nearest wetland was 2 miles away as a crow flies. They sprayed our neighborhood. No bats, birds, squirrels, chickens, geese or anything died. My pond still has fish in it. I am really tired of anti-science people giving emotional cries to hysteria to ward off the boogie man. I suspect many of the same people are anti-vaccine too.

Good article, but missing some key points. There was only a 4-6 hour window to opt out.

I live in Kalamazoo and I opted out. I’m also a Beekeeper, in Barry County where they did spray. We opted out there too, but that only protects within 1000 feet of the property line. Bees travel up to 3 miles to gather pollen. We were instructed to close our bees in the hive for min 24 hours, and cover with damp sheets, and to provide fresh water for a week because their natural drinking area would kill them. We also had to pull any honey before the spraying, because anything left behind would no longer be considered fit for human consumption. This is the food that the bees use to live through the winter – poisoned.

This chemical kills indiscriminately, including fish, cats, birds, bats and other insects that control mosquito populations. Upset that balance, and you’ll end up needing to spray every year, like Florida and other states do.

The SDS sheet instructs not to spray on or near water, not on actively blooming plant life or weeds. That’s plausible if ground spraying, but not via airplane especially at night.

Here’s the thing – they’re spraying to protect human life. However, we humans are the only ones with the means to protect ourselves from mosquito bites, by staying indoors at dusk, protective clothing, repellents, heck, even mosquito netting if needed. The wildlife and insects don’t have that ability.

Thank you Kim, I reside in nearby Allegan County with many organic farms and bees nearby. The opt out was helpful for us, yet we wonder locally how things will look next year.

“In a typical year, the adult mosquitoes that spread EEE would be dying out in Michigan by late August. This year, though, they persisted well into the fall .”

Longer warm seasons is just one of the problems we will be facing more frequently with the advent of Climate Change, as it encourages these pesky mosquitos and ticks to spread these diseases further and further.

what is wrong with people?? I am severely Chemically sensitive & it is to Chem. Pesticides!!! why in the heck, ha, do they not use BTI a safe, effective, way to kill mosquitos and NOTHING ELSE!! It is the same as mosquito Dunks! It can be fogged, & sprayed. Chemical pesticides alter DNA & the damage is passed along to future generations. Enough is ENOUGH!!!

This barely even touches on the knock-on effects of the spraying. Even more than the human-specific health effects, what do we know about the environmental effects? Pollinators are not the only worthwhile kinds of insects, and not all pollinators work during the day. Everyone is so worried about the honeybees, but honeybees aren’t even native to North America. Worry more about the insects that aren’t famous.

Even if you could guarantee that it only kills mosquitoes, I haven’t been satisfied that mosquitoes aren’t ecologically-important. I know at least that they’re a major food source of dragonflies and damselflies.

The simple fact is that these are substances that are designed to kill insects. If you spray them out of a plane, you’re going to kills millions of insects, and 99% of them are going to be something other than mosquitoes. It’s an ecological catastrophe. Tell people to start taking responsibility for avoiding mosquitoes if they’re so worried about mosquito diseases. You can’t say “tens of thousands of people didn’t object,” because 10s of 1000s of people don’t have the understanding of the environment that elected officials should have if they’re going to be making decisions like this for others.

While the American Mosquito Control Association may indeed be a “non-profit”, its members are not: they make (and profit from) all sorts of poisons.

Near my community, spraying for mosquitos is usually a yearly thing. However, often the spraying is done over the nearby Flushing Meadow Park (home to the 1939 and 1964-65 World’s Fairs — not over our HOUSES. Assuming the accompanying photo is of the area in question (I understand it may not), then given the general wind direction (hopefully AWAY from people), they can spray the FOREST AREA and AVOID THE neighborhood on a given evening (when spraying is usually done around here).

I believe, people want a quick fix for the nuisance of the mosquitos and are using the health concerns of the public as the reasons for doing it. Today, most people want an instant fix. Spraying mosquitos has become a massive money maker for businesses (lawn services, mosquito joe type services, They are spraying everything in their path, and by using scare tactics they are encouraging most to participate in “supposedly keeping people safer”. Now, we face these toxic poisons everywhere, not just in the rural sectors where insecticides were put on crops but now even in urban corridors in almost every backyard. One must wonder how this is effecting all other parts of the ecosystem. Those poisons are getting into our air, water, soil, runoff, birds, bats and all animals who eat insects are slowly being poisoned. I have already seen numbers of insects and birds dwindle in my small area I live in. It is happening across the world by more than just spraying. Our environment is being attacked by the all mighty dollar. Mark my word, this will not be going away and we must understand we have to be aware of the poisons we use because they affect us all, humans, plantlife, wildlife and insects. Wake up everybody because we (humans) are our own worst enemy.