Connecting the Dots

Michael Parker scrambles to the top of Vulture Rock just as the first drops of rain start to fall. Through the mist, the vast green tapestry of southern Oregon unfolds below him, a patchwork of recently logged and unlogged forests, river valleys and meadows. The broad ridge leading up to Surveyor Mountain marches off to the east, bristling with conifers. Between the far horizon and the low clouds, the snowy flanks of Mount Shasta wink in the California sun.

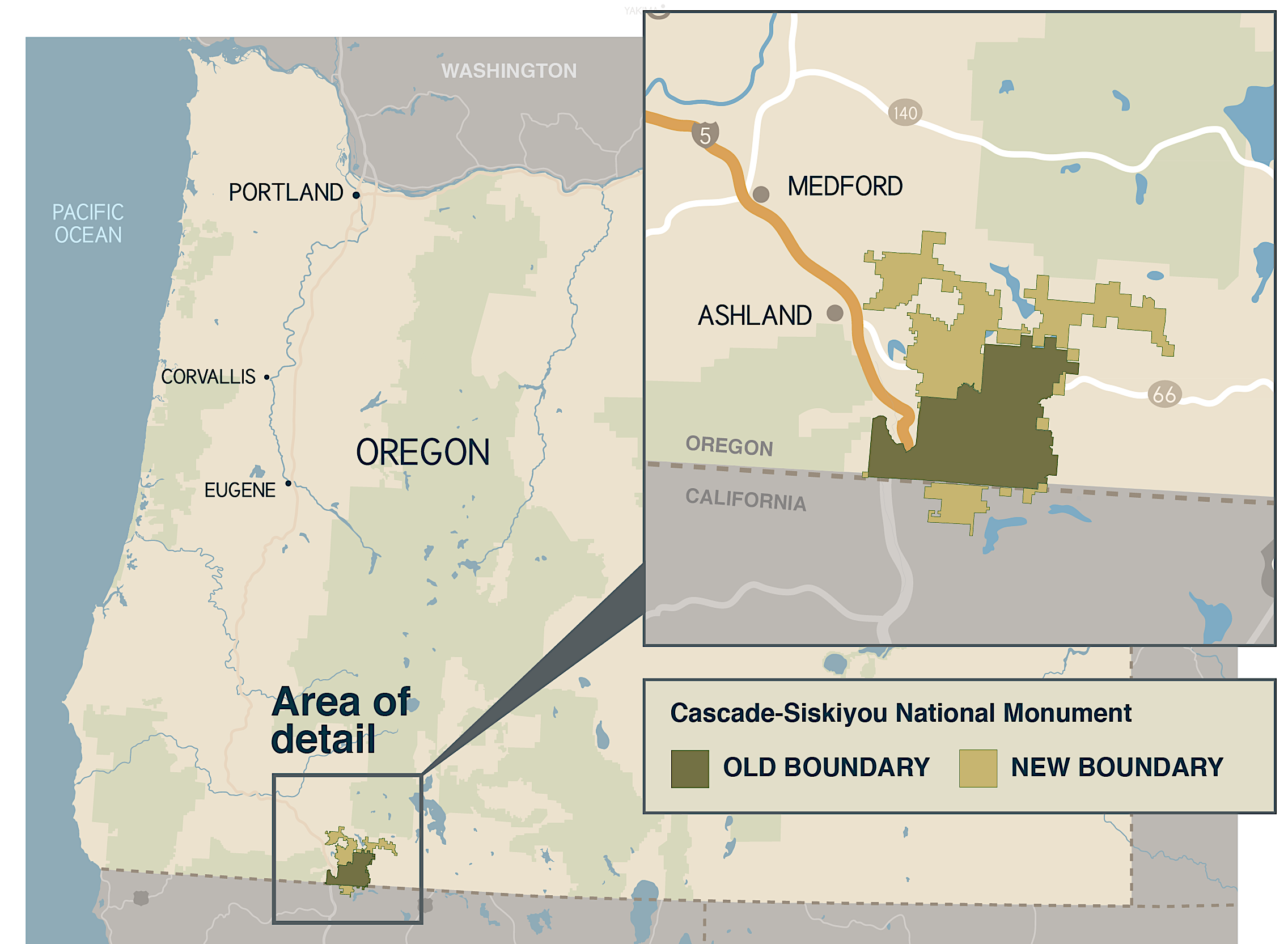

From the precarious summit, Parker, an ecologist at Southern Oregon University in nearby Ashland, points across the valley to the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. It became the latest beneficiary of President Obama’s environmental legacy when he announced the expansion of its boundaries on Thursday to include, among other places, the spot beneath Parker’s feet. The reserve was established in 2000 by President Clinton, and was the first national monument ever set aside solely to protect biodiversity. Though it’s not obvious to an untrained eye like mine, this spot on the California-Oregon border sits in one of the most ecologically rich regions in North America.

The monument is home to imperiled species like northern spotted owls and Pacific fishers, varieties of trout and lilies found only in this part of the world, and more than 130 kinds of butterflies. When I ask Parker about any particularly iconic species, he balks. “It’s anathema to the idea of biodiversity.”

Parker was among a group of scientists who had come to fear that the area’s ecological treasure chest wouldn’t survive inside the existing boundaries of the monument. In 2011, their research found that many of the region’s key species rely on habitats that lie outside of the monument’s existing boundaries, and in areas that face intense pressure from logging, grazing and development. They also warned that the monument’s modest size left its denizens particularly vulnerable to climate change — a threat not mentioned in its founding proclamation or management plan.

As it was, the reserve consisted of disjointed parcels of public land totaling just 66,000 acres, and it didn’t provide continuous protection across elevation gradients, or between important geographic features. “The original boundaries weren’t drawn in the right places,” Parker says. “They were political, not biological.” In the spring of 2015, 85 scientists from dozens of universities and non-profits — including Parker — signed a letter supporting the expansion.

Environmental activists and Oregon lawmakers lobbied for it, too, and this week, President Obama turned those hopes into reality. Using the authority granted to sitting presidents under the Antiquities Act, he added an additional 48,000 acres of federal land to the monument, along with establishing and augmenting four other monuments from Alabama to California.

“The Cascade-Siskiyou landscape has long been a focus for scientific studies of ecology, evolutionary biology, wildlife biology, entomology, and botany,” the President’s proclamation declared. “The expansion area provides an invaluable resource to scientists and conservationists wishing to research and sustain the functioning of the landscape’s ecosystems into the future.”

To be sure, the expansion achieves many of its proponents’ goals, including providing a greater range of elevations and habitats, and linking them together so that species can move freely between them. It’s an example of establishing greater landscape connectivity, which researchers increasingly recognize as crucial to helping species adapt to climate change. Scientists contend that less than half of the remaining natural areas in the United States are adequately linked to help species escape warming in the coming century.

Not everyone is happy about the news, of course. Opponents worry that the expansion will restrict access to public lands and impact the area’s logging and ranching industries. In particular, some ranchers worry that they will be pressured off public lands where they now graze cattle. Similar tensions have underpinned other recent fights over public land use, including the armed occupation of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge in Oregon last winter and efforts to block the creation of new monuments across the West, some of which proved unsuccessful.

But Parker and many others are pleased that the expansion squeaked through just a week before Inauguration Day. “It was getting right down to the wire,” he says.

Few people other than ecologists know of the exceptional biodiversity in the Cascade-Siskiyou region. Three mountain ranges collide here, forming a tangle of topography that has long served as a biological melting pot. Coastal plants and animals that evolved in the ancient folds of the Klamath and Siskiyou Mountains mingle with alpine residents of the Cascade Mountains, which extend hundreds of miles to the north. Desert species from the Great Basin creep in along the Klamath River.

The Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument sits right at the heart of this intersection. It encompasses a high-elevation land bridge that runs east to west, connecting its eponymous mountain ranges. The northern flank of the bridge swoops down toward the lowlands of the Rogue River Valley; the southern side towards the Klamath River. “The richness that it contains within its small footprint is a reflection of the fact that lots of things move through this connection, and a lot of them stay,” says Pepper Trail, an ornithologist and conservation chair of the Rogue Valley Audubon Society.

Forests of stately Douglas fir abut golden grasslands, sagebrush and scrubby chaparral. Oak trees rub shoulders with junipers, and western meadowlarks carouse with uncommon bedfellows like magpies, residents of the Great Basin. Tom Atzet, a now-retired U.S. Forest Service ecologist, argued that the area was more than a biological jewel. “It is an important link for migration, dispersion, and the process of evolution in the Northwest,” he wrote in a 1994 letter to the Soda Mountain Wilderness Council.

Many say credit for getting the original monument established belongs to Dave Willis, the dogged chair of that council, who has also played a leading role in the expansion effort. Now 64, he sits next to Parker on a slab of slick volcanic rock, wearing a blonde and white-speckled beard, a weary demeanor and a deadpan sense of humor. Willis lost his fingers and feet to frostbite in a climbing accident many years ago, and when I unthinkingly ask him if he needs a hand wrangling his gear onto his horse, Cat, he quips, “I need two.” But Willis’ disability doesn’t stop him from getting around the backcountry. In fact, he’s the one who first brought Parker to Vulture Rock, because its high vantage offers an excellent opportunity to view a landscape that, back in October, Willis only hoped would be part of the monument’s future.

Now that the expansion has been approved, the monument will encompass much of the area between Vulture Rock and Surveyor Mountain, boosting the highest point in the monument by over 400 feet, filling gaps between the monument and nearby national forest lands, and protecting a large swath of high-elevation conifer forest. That will benefit many cold-adapted species, including birds like the gray jay, which survives the winter by feeding on half-digested wads of stockpiled food that will spoil if temperatures rise above freezing, Trail says.

On the other end of the elevation spectrum, the expansion includes private land that’s already being managed for conservation in the foothills east of Ashland, and which provides a gangplank for valley dwellers seeking cooler temperatures. Redrawing the monument’s boundaries also incorporated patches of old growth forest to the north of the existing monument, which host spotted owls, Pacific fishers and, in recent years, wolves.

The expansion doesn’t accomplish everything researchers recommended in their 2011 study. The final boundaries don’t link the monument to another lobe of national forest land to the north. They also don’t provide as much protection as scientists had hoped for the upper reaches of streams that flow into the existing monument, and are home to native redband trout and rare freshwater snails. “It’s probably not devastating, but it will have an impact,” Parker says. Mostly, he’s frustrated that, again, political considerations have compromised some of the ecological benefits of protecting this landscape.

The Bureau of Land Management already oversees the expansion lands, as well as the monument. But unlike the monument, which is managed for the purpose of protecting biodiversity, these outlying tracts had been used for a variety of purposes, including for wildlife and recreation, as well as logging and grazing — the historical anchors of the local economy. By managing them all for conservation, advocates hope to create a more intact, connected landscape that offers species a better chance of surviving climate change. These changes won’t simply benefit the species that reside in the reserve, Willis says, but also those that might travel through it en route to friendlier climates. “We want an ecological rope.”

Even without climate change, connectivity plays an important role in preserving biodiversity, says Josh Lawler, a landscape ecologist at the University of Washington. “There’s a general thought that if you reduce connectivity, you reduce viability,” Lawler says. While isolation can spur the evolution of new species, disconnected populations struggle to maintain a steady supply of new individuals — and genes — that help prevent inbreeding and increase resilience to threats like disease.

But the fact that climate change will force many species to migrate makes connectivity even more essential, Lawler says. “It adds this extra twist.” Most species evolved to thrive in certain environments, and evidence from past climate changes suggests that many moved around, pursuing the conditions they needed to survive. Now, however, species must navigate a landscape fragmented by cities, roads, industrial activities and agriculture.

A 2009 study concluded that improving landscape linkages is the top recommendation for preserving biodiversity in an era of global warming.

That’s why scientists have increasingly honed in on the importance of connectivity. A 2009 meta-analysis found that improving landscape linkages is the top recommendation for preserving biodiversity in the era of climate change. And there have been a suite of recent studies aimed at identifying, which specific corridors species might use to escape the heat.

In one, led by Travis Belote of the Wilderness Society and published earlier this year in the journal PLOS One, researchers highlighted unprotected regions that could provide important connections between existing protected areas. (The area around the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument is one of many across the country that pops out as a “high value” corridor.)

When planning specifically for climate change, Lawler and others have pushed for a more sophisticated approach: identifying corridors that allow species to migrate along so-called climate gradients. Such corridors take into account how species actually move through the landscape, and allow them to pass through successively cooler habitats, rather than having to cross through inhospitable terrain in search of appropriate conditions.

“Connectivity to address climate change, if it’s done right, should actually help an organism get from where it is today to where it might need to be in the future,” Lawler says.

In many cases, climate connectivity requires maintaining links between low- and high-elevation habitats, or between low- and high-latitude areas, both of which provide built-in temperature gradients. It also includes maintaining connections to habitats where species might find cool refuges without having to move too far, like river valleys and north-facing slopes. (Lawler says the monument expansion will help accomplish all of the above, as well as support larger, more resilient populations.)

Today, however, only 41 percent of natural areas in the U.S. are sufficiently connected for species to keep pace with the climate changes predicted for the next 100 years, according to a recent study by Lawler and his colleagues. The problem is particularly acute in the eastern U.S.; there, less than 2 percent of undeveloped areas link up with places where today’s climate conditions will exist tomorrow.

That’s why many have argued for strengthening existing connections like the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument and for creating additional linkages. Lawler and his team found that establishing new climate corridors could boost the fraction of climate-connected natural areas in the U.S. to 65 percent. (Rep. Don Beyer, a Democratic congressman from Virginia, recently introduced a bill to help kick-start such efforts by establishing a National Wildlife Corridors System.)

Exactly what type of connectivity is needed depends on the species, and how easily they can move through human-altered landscapes. Birds can get by with a patch of habitat every few kilometers whereas deer and elk have trouble crossing a road. (Interstate 5 runs through the monument, forming a barrier to many creatures and leading to calls for a wildlife bridge). Certain kinds of plants actually benefit most from continuous connections, Lawler says. “Plants are less mobile, so they’re going to need suitable ground to move across.”

For places like the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, where the goal is to preserve a diversity of species, each with different requirements, the safest approach is to promote a functional landscape, says Dominick DellaSala, an ecologist at the non-profit Geos Institute in Ashland who contributed to the 2011 scientific report calling for the monument’s expansion. That means protecting entire ecosystems and biological communities across geographic features like the Cascade-Siskiyou land bridge, and along the elevation gradients leading up to it, he says. “If you can disperse and the habitat is intact, you’ve got a chance.”

The proposed expansion was welcomed by scientists and conservationists, but many others in the community, particularly those with multigenerational and economic ties to the land as ranchers and loggers, were staunchly — and sometimes emotionally — opposed. Above, highlights from a Jackson County hearing on the matter in October.

News of the expansion will cheer the diverse coalition that supported the monument’s growth. That included many local residents, tribes, and elected officials ranging from the mayor of Ashland to both of Oregon’s senators, along with scientists. “We need these large, rugged protected areas more than ever,” says Susan Harrison, an ecologist at the University of California-Davis who has worked extensively in the Siskiyou Mountains.

But the expansion dealt a blow to others.

“It’s a real tragedy,” says Jerome Rosa, executive director of the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association. Rosa says that the expansion will likely result in the “involuntary retirement” of several grazing allotments on land that will now be part of the monument. Although each monument is different and some allow grazing, the BLM concluded in 2008 that grazing was incompatible with the monument’s purpose of protecting biodiversity. The agency did not revoke permits; instead, Willis and others raised private funds to buy out the majority of grazing leases. Rosa says others will now be forced to sell because their land will become worthless. “These are honest, hard-working folks,” Rosa says. “It’s really heart-wrenching.” (Pockets of private land inside the boundaries would not be directly affected by the new designation.)

Mike Ayers, a resident of nearby Medford and president of the Oregon Hunters Association, says he and other stakeholders were left out of the planning process until late in the game, a concern Rosa shares. Ayers objects to the expansion partly on these grounds, and partly because he fears more closed roads will restrict access for hunting, recreation and fighting fires inside the monument, even though monument lands will remain open to the public. “No matter what they say, use is going to tighten around it,” Ayers says.

Some also worry that a moratorium on commercial logging inside the expanded monument could potentially reduce revenue for local counties, although BLM officials say that depends in part on how surrounding lands are managed.

Could the expansion be overturned by the incoming Trump administration? It’s a question many have been asking in recent weeks after Obama designated other new monuments, including one at the Bears Ears in Utah, and Gold Butte in Nevada. Nicole Cordan, a director of public lands at the Pew Charitable Trusts, says such a move would be unprecedented.

“While the president has the authority to create and modify monuments, the president isn’t specifically given the authority to undo them,” she says. Many legal scholars think it would take an act of Congress, though Cordan notes that it has never been tested in court. In the meantime, Republican lawmakers have introduced a Senate bill to curb a president’s power to designate new monuments under the Antiquities Act.

Still, as with many issues, the Trump Administration’s position on such matters remains unclear. In a recent speech, Trump vowed to honor “the legacy of Theodore Roosevelt,” and protect federal lands. And while his pick for Secretary of the Interior, Montana congressman Ryan Zinke, has voiced opposition to the idea of transferring federal lands to state control, he voted last week in favor of a new House rules package which would make such transfers easier — a move many Republicans hope will roll back restrictions and boost economic activity. Trump himself has also advocated for reviving extractive industries like logging. “Timber jobs have been cut in half since 1990,” he said at a campaign rally in Eugene, Oregon, last spring. “We’re going to bring them up, folks.”

As is often the case with debates over public land use, the issue boils down to balancing local economic concerns with a mandate to manage lands for the benefit of all Americans. People must decide how many cows, or how many trees, a rare collection of snails and butterflies is worth. “It’s a key issue we have to wrestle with,” Parker says.

Willis argues that the creation of the first monument firmly established the importance of the Cascade-Siskiyou’s biodiversity, and the expansion seems to reinforce it. In the steady drizzle on top of Vulture Rock, rain drips from the brim of Willis’ tan cowboy hat onto a worn blue sweatshirt. He looks anxious and tired, and not from the climb. He gazes off into the distance, across this little-known corner of world to which he has dedicated much of his life.

“This is probably the last chance to protect public lands in Oregon,” he says, “for a long time.”

Julia Rosen is a freelance science journalist interested in everything from energy to fossils to food. Her words can be found in Science, Nature, The Los Angeles Times, Orion, Discover, Nautilus, and High Country News, among other places.

This article has been updated to properly identify Dave Willis’s horse. The animal’s name is Cat, not Kat.