The Struggle of the Bighorn

Ed Partee’s truck lumbered down an overgrown dirt trail in rural Nevada. “Sorry about the road,” he said as the vehicle dipped and shook over a pothole. It was mid-morning in August, and the Montana mountain range, which looms over the Kings River Valley in the northwestern corner of the state, rose up in the distance from a sea of dry grass and charred sagebrush.

Partee is a game biologist with the Nevada Department of Wildlife, and six months ago, he helped to shoot and kill nearly 30 bighorn sheep in those mountains. Most of the animals were too sick to run. “The sheep were walking dead,” he recalled. “It was terrible.”

The animals were suffering from a deadly form of pneumonia — one that numerous studies suggest can be passed on to wild herds during contact with grazing, domesticated sheep. The bacteria that causes it has been killing bighorns since the 19th century, and while efforts to combat the disease, along with other conservation measures, have helped to stave off the wholesale disappearance of wild sheep from the American West, its persistence has hampered a full recovery. This has officials continually scrambling to stop the spread of the disease, often through large-scale culling of sick animals or enforced separations of domestic and wild herds — though usually both.

No one seems happy with these solutions. For their part, environmental and animal-rights groups decry the mass die-offs of wild sheep, and they call for more aggressive efforts to keep disease-harboring livestock at a distance. But while the separation of wild herds and grazing livestock can serve as an effective management tool, it, too comes at a cost: Ranchers rely on public lands to graze their sheep, after all, and wholesale bans on grazing have forced some herders out of business altogether.

That has experts like Partee, who likened the killing of bighorns to being “punched in the gut,” looking for other strategies — although so far, science has failed to produce viable alternatives.

“The last thing I want to see is someone losing their livelihood,” Partee said. “It’s no different than me losing my livelihood. It’s not right.”

Partee parked his truck and looked out over the valley — a thumbprint of farm houses and circular crop pivots that runs adjacent to the Montana mountains. In the winter, according to Partee, domestic sheep operators from across the state will graze their herds in these spots — about a mile away from the toe of the range.

“For this die-off, we have absolutely no smoking gun as to why it happened,” he said gesturing to the foothills. “All we know is that bighorn sheep got sick, and we saw domestic sheep down there.”

Bighorn sheep tend to stick mainly to their mountain slopes, but they do occasionally come into contact with their domestic cousins grazed on the land below. And while the species have some similarities, domestic sheep have something bighorns don’t: a bacteria known as mycoplasma ovipneumoniae. It’s a species that only afflicts goats and sheep, and domestic sheep carry the requisite antibodies to fight it.

For bighorn sheep, though, the bacteria can be disastrous. Microscopic hairs, known as cilia, serve to keep dust and other particles out of a goat or sheep’s lungs, acting like an air filter in healthy individuals. But in a bighorn that’s infected, the bacteria glues itself to these hairs, causing them to malfunction.

“What was once guarding your respiratory tract is now incapacitated and lying on the floor,” said Peregrine Wolff, a wildlife veterinarian with the Nevada Department of Wildlife. The airways become an open door for all sorts of bacteria, including pasteurella, to enter, and the lungs swell with infection.

Wolff compares it to the smallpox epidemic.

“The stuff that would make us sick when we came over and colonized the New World would decimate people who had never been exposed to it,” she said. “Your body has no memory of the disease so you can’t make antibodies quickly enough to fight it.”

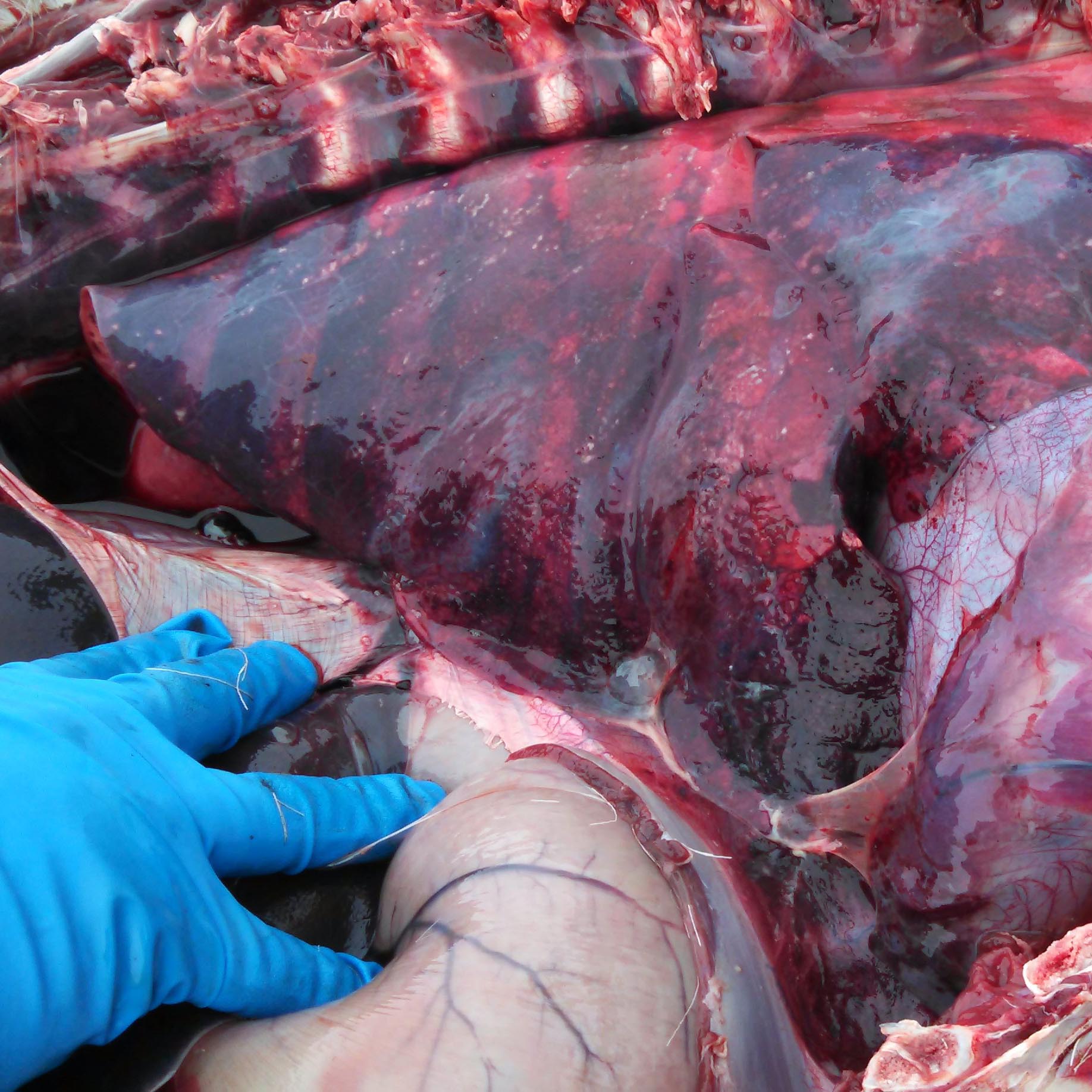

Partee remembers performing a field necropsy on a sick ram he euthanized last January. Using a knife and a pair of garden shears, he lopped off the animal’s head and pulled out the animal’s respiratory tract and liver.

“Most lungs are pink and fluffy,” he said. These were swollen and covered with a white bacteria. They had the appearance of blue cheese and swam in a pool of foul, yellow liquid.

“It’s just an awful death,” he said.

Bacterial pneumonia first struck bighorn sheep in North America during the late 19th century. In less than 50 years, the population had declined by nearly ninety percent. They have since rebounded to around 85,000 sheep — less than 10 percent of their historic population peak — but pneumonia continues to hamper full recovery of the species. At least 14,300 sheep have succumbed to the disease since 1980, according to a conservative estimate by the Wild Sheep Working Group, a taskforce of federal, state and provincial wildlife officials.

Partee first noticed the Montana mountain herd was sick last December. Responsible for monitoring the disease’s spread, he began working sixty hours a week and surviving on Clif bars, coffee and the occasional gas station burrito. “Every few days you’d have another one missing,” he said. Within a few weeks of the outbreak, more than two-thirds of the Montana mountain herd was dead, and the rest were ticking time bombs.

Deep snows had essentially quarantined the sick herd for most of the winter. But as spring approached, the snow began melting and the risk of transmission to other, healthier herds, became too great. Partee showed me a photo of a young ram he found a month prior to the eradication. The animal’s head was cocked upwards towards to the sky, as though it was looking for a bird, its nose jammed with snot, legs stiff and eyes glazed white. “It actually died just like that,” he said.

With nearly 100 bighorn sheep living less than a mile away in the Double H mountains, Partee and his colleagues at the Nevada Department of Wildlife made the decision to depopulate the Montana mountain herd. They contracted U.S Wildlife Services sharpshooters to carry out the job. Using a helicopter and a shotgun, they shot and killed 24 bighorn. Afterwards, Partee and his supervisor, Mike Scott, found and eliminated three more. It wasn’t enjoyable work.

“You’re nurturing this herd for fifteen years and then something like this happens,” Partee said. “It’s really disheartening.”

But when I asked If he regretted the decision — one he helped make — he said no.

“I’d do it again if the situation was the same,” Partee said. “There was more at risk by not doing it.”

Depopulation has been used by at least two other western states and a Canadian province since 2000. Utah wildlife officials killed 25 diseased bighorns in 2010 and Washington state wildlife officials killed 63 in 2013. But it isn’t a solution so much as a stop-gap — as are attempts to keep the bighorns and grazing domestic sheep separated.

Currently, scientists and conservationists are looking into alternative ways to stop the transmission of the bacteria. But there appear to be no simple answers.

In 2010, under pressure from environmental advocacy groups, the U.S. Forest Service closed 70 percent of the public sheep grazing allotments in the Payette National Forest in Idaho. At least two ranching families claimed they were put out of business by the decision, and they — along with the Idaho Wool Growers Association — sued the U.S. Forest Service.

“After 60 years of raising sheep, it’s heartbreaking,” said Gail Carlson, the wife of a sheep rancher who says he lost his business as a result of the grazing bans, which were upheld in a district court last March.

Currently, scientists and conservationists are looking into alternative ways to stop the transmission of Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae. A program by the National Wildlife Foundation, for instance, pays ranchers thousands of dollars to forfeit their grazing rights in places where bighorn sheep are present. And, while vaccines are ineffective because there are too many different strains of the bacteria, breeding disease-free domestic sheep is also a possibility.

“Instead of separating the sheep, we’re trying to separate the disease from the sheep,” Dr. Thomas Besser, a veterinarian and researcher at Washington State University, said.

Recently, his team discovered that domestic lambs weaned before they are eight weeks old do not carry Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae – even if their mothers bear the disease. They’re currently raising a flock of 40 to 50 disease-free domestic sheep. While the logistics of replacing entire herds of domestic sheep – some of which number in the thousands – with disease-free sheep are daunting, Besser believes that it could succeed with smaller flocks in high-risk areas.

“I expect that a substantial proportion of those operators might be willing to get rid of Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae,” he said. “At least that’s my hope.”

In the meantime, while continued research and land buyouts are providing potential avenues for addressing a decades-old problem, a quick and simple end to the conflict between these two icons of the American frontier – bighorn sheep and sheep ranching — might still be too much to ask for.

“If we could figure that out,” Partee said, “we’d be heroes of the West.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

What you describe here is horrid, having to kill animals to save others is maybe necessary, but a discouraging action to have to take. What I would object to out of this article, is the wholesale accusation of goats along with the sheep as a danger to these animals as wildlife biologists and land managers are almost always eager to do.

While there is a lot of information to indicate that sheep DO carry these pathogens, there is, as well, a paucity of research to indicate that goats do. As a point of fact, with the advent of the determination that mycoplasma ovipheumoniae is the ‘first cause’ of Bighorn Sheep pneumonia, goat packers like myself embarked on a project to have our animals tested. The question? Do our packgoats carry this pathogen? The testing of 563 animals failed to turn up even one that tested positive for Movi.

So the second question becomes, if our animals do not even carry the pathogen, and if we can test them to insure that they are disease-free, why in the world are we being restricted out of the forest? We shouldn’t be is the only answer.

I am a 75yo senior who uses goats to carry what I no longer can. Without my animals, I am washed up as a hiker. I DO NOT want to see that happen for no reason. And for now, there is NO REASON why I should not be able to access the forest with my animals.

A land of many uses. Right. I’m one of them!!

The problem with goats comes from the goats raised in the presence of domestic sheep from my understanding. The goats then start to carry the same disease causing organisms that lead to pneumonia. The big die off in Hells Canyon was started by a domestic goat in 1995 and was identified in that year. Land managers are sensitive to this concern. We later had a major die off again higher up the Canyon that destroyed a herd of over 125 wild sheep that occurred after I identified a goat grazing situation less than a air mile difference from them where 1500 domestic goats were being used to graze for weed control. This kind of thing makes it extremely difficult for land managers. I’m pretty sure that llama may be fine, but asking Dr Besser would be good. Washington State University is the best on wild sheep and domestic sheep disease research.

Your basic premise would be right if only the facts were right. In point of fact, almost all Pack Goats go directly from the breeder, to an isolated pen on the owners property. I personally know of no other goatpacker that raises sheep as well as goats. We have these animals to pack with, and that is what they are used for. Once my guys leave the breeder, they only know a couple or three others that they pack with, and live with for life.

Another very basic issue, is that the current pathogen of interest, mycoplasma ovipheumoniae in an experiential sampling of 570+ packgoats, was found in very, very few. My guys, for example, were a part of that study, and were test-negative. In point of fact #2, if my guys can be tested, and shown to be test-negative, they put NO Bighorn Sheep (BHS) at risk, even if they were to somehow get close to a BHS.

And another point, it has just been revealed that both bison and deer also carry Movi. This is a complex issue, but NOTHING about it would indicate that I pose a risk to BHS by taking my 4 boys into any wilderness area.

We are well familar with Dr. Besser’s research, and there are significant issues with it that we are addressing.

Larry Robinson

NAPgA, Past President

Nate,

Thanks for your efforts to bring this plight of wild sheep conservation to light in this new Magazine, “Undark”, where as its founders state, is a publication where science collides with politics and culture.

Mike