Joshua Gordon Wants to Remake Mental Health Care, on a Budget

Dr. Joshua A. Gordon, the new director of the National Institute of Mental Health, took office in the final year of Barack Obama’s presidency. But he has this much in common with Obama’s successor: He has little patience for incremental reforms.

A 49-year-old psychiatrist who made his reputation as a brilliant researcher of mice with mutations that mimic human mental disorders, Gordon is convinced that radical changes are needed in the treatment of illnesses like schizophrenia. In an interview in his office at the NIMH campus in Bethesda, Maryland, he lamented that while modest improvements have been made in patient care over the last few decades, we don’t know enough about the brain to “even begin to imagine what the transformative treatments of tomorrow will be like.”

Few psychiatrists would disagree that change is overdue. Take depression: Current approaches, which employ drugs like Prozac or cognitive-behavioral therapy, or a combination of the two, can relieve major symptoms in only some patients. The hope is that “precision medicine” — treatments targeted to the specific biological makeup of the patient — can do for psychiatry what scientists like Gordon’s Nobel Prize-winning mentors J. Michael Bishop and Harold E. Varmus did for cancer treatment a generation ago.

Unfortunately, as Gordon is well aware, mental illness is particularly challenging in this regard. In contrast to many types of cancer, where one genetic mutation can cause unregulated cell growth, psychiatric diseases rarely stem from any single faulty gene; instead, they are typically rooted in a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and cultural factors.

Gordon grew up in the Washington suburb of Silver Spring, Maryland, and his career has now brought him full circle. Last September he left New York City, where he had been an associate professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center and a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, to lead the NIMH. With its annual budget of $1.5 billion, this federal agency is the world’s largest funder of psychiatric research.

As Gordon defines it, the job involves both advocating for the mental health needs of Americans and developing science to guide policymakers and clinicians. He is “very excited” by the mental health provisions included in the 21st Century Cures Act, which both houses of Congress approved by overwhelming majorities late last year. The law allocates $1.5 billion in funding over the next 10 years for Obama’s BRAIN Initiative, in which researchers at the institute play a key role. (The acronym stands for Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies.) It also strengthens enforcement of the Obamacare requirement that health insurance cover treatment for mental illness.

Of course, Gordon concedes that funding prospects are uncertain at best. In March, in a budget blueprint that offered few specifics, President Trump proposed cutting funding across all branches of the National Institutes of Health by about $6 billion a year, or 18 percent. But a few weeks later, Congress pushed back and actually raised NIH funding by $2 billion, which included a $110 million supplement to Obama’s BRAIN initiative, for this year.

Despite the longstanding support for mental health research from legislators on both sides of the aisle, in mid-May the president proposed trimming NIMH’s 2018 budget by more than $300 million, though again he offered few details. (Gordon wouldn’t comment on the proposal.)

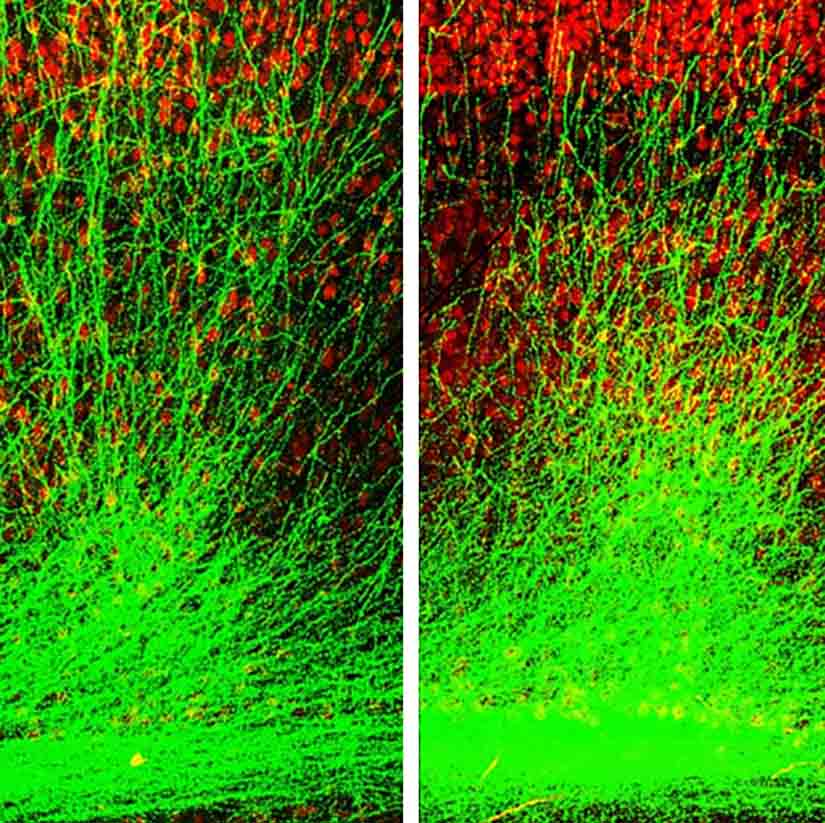

In his doctoral dissertation at the University of California, San Francisco, Gordon pioneered the use of sophisticated genetic manipulations in mice to learn about the plasticity of the visual cortex.

In his lab at Columbia, he conducted numerous mouse studies on neural activity, with important implications for such psychiatric diseases as schizophrenia, anxiety, and depression. In a seminal paper published in Nature in 2010, he demonstrated how a genetic mutation on chromosome 22, which is known to boost the risk of schizophrenia 30-fold, damages the connection between key parts of the brain. As Thomas R. Insel, Gordon’s predecessor at NIMH, observed that spring, “For the first time, we have a powerful animal model that shows us how genetics affects brain circuitry, at the level of single neurons, to produce a learning and memory deficit linked to schizophrenia.”

Like Insel, Gordon plans to emphasize basic research on brain biology. That’s why he wants to continue the work launched several years ago by Insel on the Research Domain Criteria, known as RDoC, the controversial new framework for studying psychiatric disease. In contrast to the DSM, psychiatry’s longstanding diagnostic bible, which identifies broad disease categories such as depression or schizophrenia, RDoC breaks down behavior into small component parts such as apathy. While the DSM has been successful in allowing clinicians to communicate with each other, Gordon says, “as a method by which we try to understand the neurobiologic basis of disease, [it] has failed miserably.” As he notes, RDoC is not designed to replace the DSM. Its promise is that it offers researchers a useful tool to link behavior with brain function.

RDoC is still a work in progress, and Gordon proposes tweaking it. It “was built in much the same way the DSM was built,” he says, “which is to get a bunch of experts in the room and ask, ‘How is behavior organized?’ We really should have more of a data-driven approach.” To come up with the basic building blocks of behavior, he believes that researchers should instead conduct a large battery of behavioral tests on hundreds of individuals, if not thousands.

Gordon argues that such a big-data approach could be useful across his agency’s entire portfolio of research. He cites the Human Connectome Project, a multi-campus research effort modeled on the Human Genome Project. The mental health institute originated the idea, saw it through, and now stores the data. Derived from brain scans collected on 1,200 healthy individuals, the project, completed in 2015, provides a basic map of the brain and the neural connections between various brain regions. When you do this type of testing for that many people “you get tremendous statistical power and confidence in your results,” Gordon says. “We have a basic map of the brain and how it’s connected that other researchers can tap into. They can compare their datasets to it, and they can go looking in that data, because it’s publicly available, for information about how the brain functions and how it’s structured.”

And these follow-up studies have already begun. The Austen Riggs Center, a residential treatment facility in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, is now mapping the brains of a sample of its patients, who suffer from complicated psychiatric disorders. “We want to compare their characteristics to those of the normal subjects in the Human Connectome Project,” says Andrew J. Gerber, the medical director of Austen Riggs. “We hope to identify a brain region that might be amenable to change by a particular intervention — say, a new medication or type of psychotherapy.” Even though he specializes in long-term psychotherapy, Gerber is a big supporter of Gordon. “Josh focuses on neurobiology, but he also did clinical work at Columbia and his vision represents a deep integration of all perspectives,” he adds.

Gordon says he chose to do his residency at Columbia because he wanted to ensure he “got a rigorous clinical education.”

“My experiences with patients have had a big impact on me,” he adds. He was deeply affected by the fierce independence of a rail-thin middle-aged woman with schizophrenia, whom he treated in an inpatient unit during his first psych rotation at UCSF.

“Her teeth were all falling out, and she could barely put three words together,” he says. “After I put her on antipsychotic medication, she began speaking, and the first thing she said was, ‘I am not staying here.’ It made me realize that there is a person underneath this devastating illness.”

While Gordon was a popular choice among psychiatrists to lead NIMH, he does have his share of critics. Their main concern has less to do with him personally than with the overall direction of his agency over the last two decades.

Founded in 1949, the National Institute of Mental Health used to take a much more hands-on approach to treatment. In the early 1960s, when the federal government decided to deinstitutionalize many patients locked up in state psychiatric hospitals, the agency worked closely with community mental health centers to devise clinical care for the chronically mentally ill. But in the early 1990s, its role changed when the newly established Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration began overseeing the delivery of services to psychiatric patients. Ever since the 1990s, which it designated “the decade of the brain,” the mental health institute has focused primarily on basic research.

The psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey, founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center, a nonprofit based in Arlington, Virginia, that supports patients with illnesses like schizophrenia, argues that NIMH has strayed too far from its original mission. Torrey is impressed by Gordon’s qualifications, but he worries that he will not sponsor enough research on serious mental illnesses. “The share of the institute’s funding devoted to serious mental illnesses has gone down steadily over the last 20 years,” he says.

“The families of patients are upset that what it has done has not led to any new drugs or treatments,” he added.

Allen J. Frances, a former chair of the department of psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine, who headed the task force behind DSM-IV, worries about the plight of America’s chronically mentally ill — particularly the 350,000 who are in prison and the 200,000 who are homeless. “The rest of the world doesn’t criminalize the mentally ill,” says Frances. “This is a crisis. Brain research is wonderful, but the agenda of the National Institute of Mental Health is unbalanced. And none of its research efforts over the past 25 years have helped a single patient.”

Richard A. Friedman, a professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, who specializes in psychopharmacology, agrees that the mental health institute’s decades of brain research have yielded few tangible results. Friedman, who is also a contributing op-ed writer for The New York Times, faults the institute for spending only 10 percent of its research funding on clinical trials research — and just half of that on psychotherapy clinical trials. “Looking at the basic mechanism of disease is useful, but we can’t wait for complete knowledge to explain all of human behavior,” he says. “Psychiatry as a whole has been neglecting the benefits of both psychotherapy and self-understanding.” Friedman argues that Gordon should fund more studies designed to help patients now coping with such common disorders as depression or anxiety.

When asked to respond to these critics, Gordon defended the institute’s priorities. “NIMH spends, on clinic trials, the same percentage as the rest of the NIH,” he says. “And you could argue that we should be spending less because we know less about the brain.

“We actually are spending a significant amount of money on clinical trials and other kinds of research that have impact on patients.”

Gordon acknowledges that psychiatry has not come up with any significant new treatments since the advent of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (antidepressants such as Prozac) and the second-generation antipsychotics (such as Seroquel) decades ago. That’s precisely why he thinks the institute should continue to invest so heavily in basic science. “Our first priority is to find novel targets in the brain so that we come up with transformative treatments,” Gordon says. He suggests a new medication that directly addresses a flaw in neural connectivity, for example and says he wishes more drug companies were still involved in this kind of work.

Gordon is not interested in funding studies that do not aim high. “Some people want to take a treatment that we know works and test it in a different population or tweak it slightly, but we do not to want to make modest changes; we want to do things that matter.”

Despite his emphasis on the long game, Gordon’s research portfolio does include some initiatives that can help contemporary Americans. “The reason to focus on suicide is that modest improvements can make big differences,” he says. Out of the 44,000 Americans who committed suicide in 2015, “virtually all of them [had] been to a primary care doctor in the last 12 months.” Gordon explains that there are evidence-based methods to screen for high-risk individuals, which can get them into psychiatric care. And once these individuals have been identified, Gordon says, researchers can look at what types of treatments will actually keep them alive.

Gordon also wants to increase access to an evidence-based treatment approach called coordinated specialty care, developed by the NIMH psychologist Robert A. Heinssen, that helps patients between the ages of 15 and 25 after a first episode of psychosis. By providing an array of clinical services, including assertive case management, individual or group psychotherapy, and medication, this intervention is designed to prevent the onset of chronic mental illness.

Though Gordon hopes to revolutionize psychiatric care, he is still a strong advocate for today’s standard treatments, such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, and psychotherapy. “We know that they work — only modestly, but they do work,” he says, but adds: “These do make huge differences and improve patients’ lives. But they don’t improve them enough in many patients, and unfortunately, there are many patients who don’t get that improvement. And this is the problem that fuels my desire for transformative treatments.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I was diagnosed Bipolar Schizo affective some 30 yrs. ago. When I look back, at the time of my diagnosis, I had become what I call, Broken. Spiritually, physically, & mentally. I had endured a very long bout of trauma, and could not go on. I became detached at times from reality.My mother had to take a leave from her job to care for me. I began sleep walking, so brother had to stay with me at night. I was as a 36 yr. old toddler. My mind lost all common sense. My family enrolled me in psyche daycare, where I was given psychotropic drugs. Mellaril, Prozac, & a handful of pills for all the side effects. It did nothing more than sedate me, it cured nothing. For yrs. & yrs. I suffered torturous side effects. It caused me physical pain and embarrassment to be in society. My hands shook violently and I would have spit come out of my mouth when talking to others, not drool, it would shoot out onto others. Thirty yrs.later I still rock while I sit, and my legs and feet continuously move unknowingly. And I’ve been off off neuroleptics for 15 yrs. Now I do still take an SSRI, which my brain is physically addicted too. To make a long story short, my entire nervous system feels like its been ran threw a grinder. I have severe nerve pain all through my body. Gabapentin is only a little affective. You know, the psychiatric profession has treated myself and millions of others, worse than anyone could imagine. I feel betrayed & used up & physically abused by the way you treat us. I participated in a mental health community living program, by choice. When you are mentally Ill, more is expected of you than a normal person. We are very much discriminated against by the people who are supposed to care. They always want to cut funding for our care. Have you ever wondered why it cost 7-8,000 a day to stay in a psyche hospital versus 2500. a day to be in ICU, or on a Trauma unit??? Oh that was a mouthful! I personally have found that time, & God have healed me dramatically. But spend your time & money on creating medications without horrific side effects. And condition and teach society that we are humans too, not scary creatures that no one understands.

Susan:

You write about the need to train clinicians and family members who are ‘disdainful’ of the ‘medical model’, yet your own dismissal of these people is dripping with disdain. You do not explain if you are a medical care provider, so I am left to assume that you are since you apparently have dealings with social workers and clients. As a medical care provider, you dismiss the concerns of people who criticize the medical model by chalking them up as ignorant. When was the last time you actually listened to a family member like me who questioned the medical model because of the negative things our family experienced in the mental health system?

I think the medical model is great for people when it works. It should not be forced on people for whom it doesn’t work, especially those who are trauma survivors. Alternatives do exist, and they are often more helpful and more humane, but they aren’t widespread (funded) and family members are not likely to hear about them, least of all from talking to people like you, for the same reason one is not likely to hear about the benefits of solar energy from Exxon.

What family members like me are seeking for our loves ones is choice and alternatives. We trusted the medical ‘experts’ until the medical model backfired and deeply harmed our loved one. I was one of the lucky ones. My daughter survived her treatment under the medical model. But I know other parents who were not so lucky.

Yes, some people embrace their psychiatric diagnosis with great relief and consider psychiatric drugs like neuroleptics, mood stabilizers, SSRI’s and benzodiazepines to be ‘life-saving’ but these highly touted ‘success stories’ are anecdotal and they involve the lucky minority. In the aggregate, these drugs are neuro toxins, brains become habituated to them, they can be hard to withdraw from, and most importantly, they create more problems than they solve. The public is only now beginning to figure this out and the most outspoken of this new wave of critics is probably inconveniencing you in your clinical routine.

The best way to end what you call ‘disdain’ for the medical model is for the medical community to come clean and admit that much of what poses as science in the medical literature is, in actuality, junk science, bought and paid for by the medical industrial complex which includes both manufacturers of technologies and pharmaceutical companies.

“How can standards of training be raised in many social work and counselling programs?” you ask. As a family member whose loved one was court ordered to receive harmful psychiatric treatment, I fully agree with you that counselors and social workers should receive more training but necessarily in the way you want but in a way that will help these professionals protect their most vulnerable clients from iatrogenic harm, using the growing amount of scientific literature that points to poor outcomes for people who are drugged for life.

The data is clear that long term outcomes in the aggregate for people who are drugged long term is very poor. Please read Robert Whitaker’s ‘Anatomy of an Epidemic’ for a sampling of the data I refer to and that book was published before Harrow and Wunderlink completed their groundbreaking studies. Critics of Whitaker cannot provide longitudinal studies to make the case that the scientific ‘revolution’ touted by psychiatry has resulted in better outcomes because this data doesn’t exist. Quite the opposite.

The only longitudinal studies that exist show poor outcomes for the medical model. The people with a history of institutionalization for the most severe psychiatric psychotic disorders who are now considered to be doing the best, as measuring by living independently in the community, being gainfully employed, remaining married and/or in a meaningful relationship, having purpose in life, etc. are precisely that subset of non-compliant individuals who lacked faith in the medical model which led them to seek alternative ways of dealing with their extreme states and/or unusual beliefs. They are not currently taking psychiatric medication or receiving any psychiatric services, period. That is what the data shows. Mental health researchers who embrace the medical model who are not rushing to interview these recovered individuals, with the intention of dismantling the status quo, making sure that clinical practices are redesigned to be in alignment with the gold mine of data represented by this population lack all scientific curiosity, and all already dinosaurs in their field.

You describe a “large” peer specialist workforce, yet peer specialists are the first to be laid off in budget cuts and they are the last people to be consulted and taken seriously in medical treatment teams. I wish my daughter had more access to peer specialists during her institutionalization. They are a gold mine of information and a living testament to the hope of recovery. They have taught our family about the value of resiliency in the face of trauma and psychiatric abuse.

Is it any wonder that a growing number of people are skeptical about claims that another scientific ‘revolution’ in mental health is on the horizon? We’ve heard that before.

Perhaps if counselors and social workers and family members would receive more training in the scientific method, perhaps then, they would know how to differentiate between the junk science and big Pharma propaganda, and unbiased science. Skeptics would only help us out of this society morass.

I was told by my daughter’s social worker that ‘My daughter has a disease like diabetes and needs to take medication for the rest of her life.” No self respecting graduate of medical school would be caught dead saying this kind of unscientific rubbish to a patient just to make them ‘med compliant’.

Ronald Pies M.D. head of the American Psychiatric Association said “in truth, the chemical imbalance notion was always a kind of urban legend, never a theory seriously propounded by well-informed psychiatrists.” Why are social workers saying this to their clients?

This diabetes metaphor was created to keep people med compliant and you are right, counselors and social workers may not be scientifically literate enough to know the difference.

When an individual and/or a family member or counselor questions whether or not a drug may be causing iatrogenic harm or creating new psychiatric symptoms, such as uncharacteristic violent or criminal behavior, akathesia, depersonalization, movement disorders, cognitive decline, dissociation, etc. such complaints and/or criticisms will often be ridiculed or ignored by prescribers, often on the basis that medically untrained individuals have no ‘scientific basis’ for such complaints, which is of course ludicrous, since the profession of psychiatric uses no bio-markers whatsoever for diagnosing and treating a mental health disorder to begin with.

A diagnosis is made based solely on subjective observations and the behavior of individuals, which represents nearly ZERO science, yet you want to raise the scientific standards for other, non prescribing professionals?!

If you want to create higher standards of scientific rigor in other people’s professions, then start cleaning house in your own, by ensuring that your profession does none of the following unscientific things:

• Receive training from medical schools relying 25% or higher on endowments and ‘chairs’ from Pharmaceutical companies which then influence deans and their hiring decisions.

• Ignore the voices of scientists and researchers who publicly criticize the undue influence of pharmaceutical companies on clinical practices and public health policies.

• Distribute, cite, and/or endorse ghost written articles.

• Support medical journals which cherry pick drug trials for publication, such as studies in which two positive trials went to print, while the remaining five negative ones for the same drug were buried.

• Sit quietly while medical journals subsist on big Pharma ads.

• Fail to condemn direct to consumer advertising of pharmaceutical drugs which is prohibited in countries except the U.S and Australia.

• Is OK with guild organizations such as the APA relying entirely from the revenues of the DSM, a highly unscientific, highly politicized diagnostic guide, which is essentially a billing Bible.

• Hiding unfavorable trials and data between paywalls or calling it ‘proprietary data’ when the release of this data could prevent psychiatric harm.

• Overhauling what it means to give ‘informed consent’

Please note that I am not, and have never been, “the head of the American Psychiatric Association” (though I am an APA member). My comment re: the unfortunate term “chemical imbalance” should be read in the context of my detailed writings on the subject, and not used to justify a broadside against psychiatry, psychiatric diagnosis, or psychiatric medication.

Readers who want to understand some of my positions and views may see the following links:

http://www.mentalhealthexcellence.org/nuances-narratives-chemical-imbalance-debate-psychiatry/

https://pro.psychcentral.com/deborah-danner-and-the-suffering-of-schizophrenia/0016548.html

https://pro.psychcentral.com/the-astonishing-non-epidemic-of-mental-illness-an-update-on-data-in-u-s-adults-2000-2015/0016052.html

Respectfully,

Ronald W. Pies MD

“… the mental health institute’s decades of brain research have yielded few tangible results.” And yet we’re going to spend more decades on brain research in the hopes that this will yield some amazing breakthroughs?

There are valid and effective psychosocial approaches to anxiety, depression, and yes, even psychosis which should be receiving extensive research. The Open Dialog model in Finland is certainly one, using medications selectively but taking specific actions that lead to an 80% functional recovery rate, when our model results in more like 15% at best.

We should also be looking at how psychosis is approached in other cultures, in light of the two intercultural WHO studies in the 90s showing that the less Westernized medicine is in play, the better the outcomes for psychotic individuals in a particular country.

There is no reason to expect that vague categories like “schizophrenia” and “major depressive disorder” which are defined entirely by subjective behavioral characteristics will ever yield to some purely biological explanation, as even mainstream researchers have admitted that these are heterogeneous categories and that the behaviors so labeled likely have a huge range of possible explanations. The research proposed also ignores the well-established fact that over 80% of those suffering from “serious mental illness” have known traumatic histories – a MUCH higher correlation than any genetic or biological factor ever identified (I believe the best we’ve seen is about a 15% correlation, and that was with multiple genetic markers and correlated to multiple psychiatric conditions).

As for “not replacing the DSM,” not sure why that should be reassuring to anyone. Insel’s original comments are true – the DSM is the biggest obstacle to ongoing research, because it lumps people together that have nothing BIOLOGICALLY in common.

An operational definition of “insanity” is “Continuing to do the same thing and expecting a different result.” At this point, expecting another decade of brain research to yield some kind of biological targets for what are actually largely socially/culturally defined “disorders” fits the above definition of insanity. It’s time to start over!

I appreciate getting to hear more about Dr. Joshua Gordon’s agenda for NIMH.

A key issue that I didn’t see addressed yet is the current training of various credentialed clinicians. Too many clinicians who come into contact with people living with schizophrenia and their families have a disdainful view of what they call the “medical model”. Many of these workers, including but not limited to the large peer work force, have never received any science based training on the current state of knowledge about sz and rely on the psychodynamic theories to which they have been exposed. How can standards of training be raised in many social work and counselling programs?

There is a lack of appropriate training in all disciplines on how to create collaborative working relationships with family caregivers. Too often these caregivers encounter a mental health system which continues to blame them for the development of schizophrenia and which unnecessarily limits their ability to provide information necessary for the best medical and psychosocial rehabilitation choices. In this article, “Family Caregivers for People with Schizophrenia Are at the Breaking Point”, I describe some of the problems family caregivers encounter:

http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/susan-inman/schizophrenia-caregivers_b_6167104.html

Susan, Mad people have a right to use whatever services work for them. If people get better when they’re deprogrammed from their schizophrenogenic “families”, then society has to accept that. A certain percentage of people can’t be sickened by their pathogenic “families”, just so that our existing social order can be preserved. WE ALL DESERVE HEALTH, even Mad people. Deal with it!

The reality is that those suffering from Schizophrenia spectrum disorders often (50% is the estimate) get no treatment. The 2 primary reasons for no treatment are Anosognosia and lack of availability. The other 50% that do receive treatment more often then not do not get optimal treatment. For the last 11 years I have been on a personal mission to change the status quo. My son developed Schizophrenia 11 years ago. At the time my wife and I were dismayed by the low expectations of the psychiatric community and their remarkable lack of ability in using evidence based modalities in said management. Over the ensuing years with the help of like minded individuals in the psychiatric community we developed an approach that now only rescued my son but has contributed to improvements in many others so afflicted. My wife and I are both internists. We use a Biopsychosocial approach in our treatment. We use the most effective and safest antipsychotic, CLOZAPINE, and we do this with a wraparound approach that includes other medications to mitigate side effects:1. the metabolic effects/weight (metformin , SGLT-2 inhibitors, and acarbose), 2. Sialorrhea (sublingual atrovent, glycopyrrolate), 3. sedation/Cognition (coffee, nu and provigil, bupropion, donepezil, amantadine, and memantine), 4. constipation (miralax, colace, senna, dulcolax, linzess), 5 Hypertriglyceridemia (fish oil, fenfibrate), 6. risk of seizure (lamotrigine, gabapentin, and topiramate). This is only a partial list and is meant to be illustrative. Everyone’s regimen is individualized I list this as above just to give you a sampling of a rational polypharmacy approach that can significantly enhance benefits. Beyond this we have found, as sanity is restored, patients are better able to participate in their care. Further incremental improvements accrue with both cognitive and psychodynamic therapy. We continuously emphasize and then reemphasize the importance of diet and exercise especially running. We are a small practice and try to help with housing, education, and vocational training. We have been impressed by the evidence for formal cognitive enhancement therapy. We do our case management. We yearn for the day that the most effective antipsychotic is available in the most effective form (long acting injectable). There is nothing easy about the treatment of serious persistent mental illness but if adequate resources are devoted outcomes can be remarkable.

Disagreement with a quack (psychiatrists are not scientists) is not “anosognosia”. Many people IMPROVE their health when they ditch psychiatry. A potentially life-saving act defiance IS NOT PATHOLOGICAL. Fake science IS! #f*ckfakescience #MadRights #justsaynotoschizophrenogenicfathers

A sigh of great hope comes with this article. I have never read anything better to assure families that rational thinking has come to plans for scientific research into schizophrenia. And I hope to other brain diseases that have destroyed lives around the world–many of my own children, one leading to his suicide.

Please keep families informed–so a spark of hope for our l loved ones who suffer from chronic brain diseases will ease our current despair. Too little interest in scientific brain research , with no power to change this has created a special hopeless in our hearts

Very interesting and helpful story, but a bit disappointed it did not spend more time on coordinated specialty care mentioned only very briefly at the end. Given how unlikely it is that new drug treatments will be found any time soon (something I wrote about in the May issue of Scientific American) and the modest but convincing evidence for psychosocial approaches (which I wrote about in Science a few years ago) I think more emphasis should be put on how to relieve immediate suffering in patients and their families/friends.

Yes indeed, very informative article regarding the NIMH historical and current role related to mental health. I must, however, applaud Michael Balter’s comments. There are 550,000 seriously ill Americans in prisons or homeless. Incarceration and homelessness increase the level of mental illness or propensity towards mental illness for most individuals. Assuming each of these individuals have three family members, the number increases to 1,500,000 Americans suffer every day. My son has untreated bipolar I and is on the schizophrenic spectrum as I write this email. It is a high priority ti improve our current treatment of the severely mentally ill now.