Nursing Homes Overuse ‘Chemical Restraints’ on Dementia Patients

Jonathan Evans had finished his medical rounds at a local nursing home when he got a phone call. “Your patient is sexually inappropriate” a nurse at the facility told him. Evans is a geriatrician in Charlottesville, Virginia, and he had seen the patient, an elderly woman with mild dementia, earlier in the day. “She was fine,” he said. “Lovely visit.” The woman had since been discovered naked (but also alone) in another resident’s bedroom. The nurse, Evans said, wanted him to prescribe an antipsychotic “to make her behave.”

Evans denied the request. But he said the incident stuck with him as an example of how health care providers use drugs — including antipsychotics — as “chemical restraints” to control perceived behavioral problems. Evidence shows this is a widespread practice in nursing homes. A new analysis of more than 12,000 nursing homes by the Long Term Care Community Coalition, or LTCCC, a New York City-based nonprofit that advocates for elderly and disabled people in residential settings, found that more than one in five nursing home residents was being given an antipsychotic medication.

Antipsychotics have sedating effects and are justified only as treatments of last resort when behaviors such as agitation, aggression, or wandering become self-threatening to people with dementia or others around them, said Bruce Miller, a neurologist who directs the Memory and Aging Center at the University of California, San Francisco. But the LTCCC also found that hundreds of nursing homes around the country have drugging rates between 50 and 100 percent, raising what Richard Mollot, the organization’s executive director, described as “significant concerns about resident abuse and neglect.”

Dementia takes hold when nerve cells in the brain stop communicating normally and begin to die. As this occurs, people suffer progressive declines in cognitive and functional ability. Symptom onset varies from one form of dementia to the next. People with Alzheimer’s disease, for instance, lose memory first, while those with another neurodegenerative condition called Lewy body dementia may suffer sleep and behavioral disturbances at the outset and then memory losses later.

Many dementia patients suffer from depression, and episodes of agitation and aggression become more common as the disease progresses. Psychosis can also occur, often during dementia’s later stages. The delusions in dementia, however, are typically visual, whereas people with psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia, tend to experience auditory hallucinations, such as hearing voices.

According to the LTCCC’s analysis, nursing homes treat with antipsychotics at nearly 10 times the rate at which certain disorders that these drugs are considered “appropriate” for — including schizophrenia — are diagnosed in the U.S. population. Treated residents in these facilities — owing in part to their physical frailty and how the drugs interact with other medications — can suffer the consequences. Many treated patients develop Parkinson’s-like symptoms such as tremor and gait instabilities. In 2005, the Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning (now called a boxed warning) cautioning that certain antipsychotics — including commonly used drugs such as Abilify, Zyprexa, and Seroquel — put elderly patients with dementia at an increased risk of death from heart failure and infections. The FDA extended that same warning to all antipsychotic medications in 2008.

Susan Wehry, a geriatrician at the University of New England’s College of Osteopathic Medicine, said the drugs alter electrical conductivity in the heart, increasing the risk of cardiac arrhythmias. Sedated patients may not breathe deeply enough to clear the lungs when coughing, she said, which can lead to pneumonia. Immobility results in bed sores and a progressive loss of muscle tone — and thus a higher risk of falls. The drugs also have nauseating side effects that may reduce appetite, Wehry said, resulting in poor nutrition.

Ironically, antipsychotics aren’t all that consistent in alleviating dementia’s neuropsychiatric symptoms. A 2021 review of 24 clinical trials testing the drugs in dementia showed only slight improvements in agitation and a negligible effect on psychosis. An earlier review of 17 studies, which was published in 2019, concluded that a single most effective and safe antipsychotic treatment for managing dementia’s behavioral and psychological symptoms does not exist. “I’m always wondering when I start these medicines whether they’re really going to be helpful,” Miller said. “It’s a little bit of an experiment.”

“They may not work at all,” he added.

“I’m always wondering when I start these medicines whether they’re really going to be helpful. It’s a little bit of an experiment.”

Miller pointed out that people with dementia often can’t take antipsychotics at the doses needed to achieve psychiatric benefits. “The ability to go to higher doses is really limited in elders,” he said. “Someone with schizophrenia might tolerate 200 milligrams of a drug, but an elder might only tolerate 5 before they start to fall.”

What Miller and other experts find concerning is that antipsychotic sedation might simply muzzle the efforts of those who can’t speak to convey unmet needs, frustrations, discomfort, and even pain. Polypharmacy — the regular use of five or more medications at the same time — can lead to constipation, which is a frequent problem in people with dementia. Often the best solution “is not adding a drug, but subtracting a drug,” said Michael Wasserman, a retired geriatrician who formerly oversaw operations at a large nursing home chain in California. If antipsychotics blunt agitation without addressing its underlying cause, Wasserman said, then using them is tantamount to “putting a sock in their mouth and tying them down.”

Nursing homes started treating dementia with antipsychotics decades ago. However, first-generation antipsychotic drugs like haloperidol (Haldol), which was first synthesized in 1958, had an important drawback: They cause involuntary muscle movements and tics. With the arrival of second-generation versions known as atypical antipsychotics in the 1980s, drug companies saw an opportunity. The newer drugs had fewer muscular side effects than their predecessors, and that prompted the pharmaceutical industry to seek blockbuster sales by moving into indications beyond severe psychotic disease. Companies began marketing off-label uses for an array of behavioral disorders, including agitation in elderly patients.

That raised some hackles with law enforcement. FDA regulations prohibit off-label drug promotion by pharmaceutical companies, and it soon became apparent that companies were down-playing other treatment-related side effects. In some instances, companies were accused of indirectly paying bribes to pharmacies. For instance, Omnicare, Inc., a pharmacy-services provider based in Kentucky that is now part of CVS, settled a $98 million lawsuit in 2009 over allegations that it had engaged in kickback schemes, including soliciting and receiving compensation for recommending Risperdal and other drugs for use in nursing home residents with dementia-related symptoms. That same year, Eli Lilly and Company agreed to pay $1.4 billion to settle charges that it had promoted Zyprexa for the same purpose.

If antipsychotics blunt agitation without addressing its underlying cause, then using them is tantamount to “putting a sock in their mouth and tying them down.”

All the while, federal regulators were trying to confront the abuse of these antipsychotics in the elderly. A series of papers published by the Senate Special Committee on Aging in the mid-1970s, cited “ample evidence that nursing home patients are tranquilized to keep them quiet and to make them easier to take care of.” Congress later passed the Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987, which stipulated that residents have a right to be free of unnecessary and inappropriate physical and chemical restraints.

Still, antipsychotic drugging rates remained stubbornly high. Claiming that unnecessary antipsychotic use poses significant challenges to ensuring appropriate dementia care, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2012 launched a program to lower the use of the drugs when not clinically indicated. Called the National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes, the program offered training in “person-centered” care and non-drug interventions, which aim for a better understanding and response to how people with dementia view the world. The Partnership limited appropriate antipsychotic treatment to just three major mental illnesses: schizophrenia, Tourette’s syndrome, and Huntington’s disease. In 2015, CMS started flagging facilities with a track record of using the drugs for other purposes by including antipsychotic medication use in the quality care ratings on the agency’s Nursing Home Care Compare website, a public resource for consumers.

Yet according to the LTCCC’s most recent analysis, the drugs are still being given to 21.3 percent of nursing home residents, irrespective of whether they’ve been diagnosed with a major psychotic disorder.

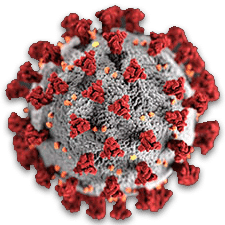

Staffing shortages at nursing homes — which have grown more acute since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic — exacerbate the problem.

A 2022 study of more than 10,000 U.S. nursing homes found that unit increases in certain licensed staffing hours was associated with a unit decrease in inappropriate antipsychotic drugging. “Optimal care for those conditions is more hands on, spending more time with patients,” said Jason Falvey, a geriatric physical therapist at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. “When nursing homes are understaffed, the shortcut is you essentially use antipsychotics as a way to control those behaviors.” Falvey coauthored a study published this year which showed that associations between low staffing and inappropriate use of antipsychotics are especially egregious in low-income neighborhoods. He and his co-authors asserted that high staff turnover and a lack of resources in such areas make non-pharmacological interventions more challenging.

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive.

Staffing has always been a problem for nursing homes — a typical facility turns over nearly half its nursing staff every year. But after the Covid pandemic “a lot of people left the field,” said Ruta Kadonoff, vice president for programs at the nonprofit Maine Health Access Foundation. Nursing homes rely on women, immigrants, and people of color for staffing, most of whom “are paid insufficiently to support their families,” Kadonoff said. During Covid, “they were asked to work in conditions that were potentially fatal to them and or their families. And they said ‘You know what? I’m not doing this anymore.’”

Research supports Kadonoff’s assertion. A 2023 analysis by Altarum, a nonprofit health care research organization based in Michigan, found that 266 U.S. nursing homes shut down between late 2019 and the end of 2022 — a decline that the authors attributed to the pandemic. The staff who remain, Kadonoff added, are deeply devoted to the work. “The fact that they care so much about the people they’re caring for lends them to being exploited, honestly, by employers,” she said. “I’ve talked to many of them over the years who say, ‘If not me, who’s going to be here for these people?’”

In January 2023, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced plans to audit nursing homes to assess their practices for diagnosing schizophrenia, to identify inappropriate drugging. The facilities record antipsychotic prescriptions on what’s known as the Minimum Data Set, or MDS, which is a standard assessment of a resident’s functional, medical, psychosocial, and cognitive status. If CMS’s audit uncovers a pattern of inaccurate diagnoses for schizophrenia, and inappropriate antipsychotic prescriptions, then the offending facility gets a lower rating on Nursing Home Care Compare.

An emailed response to Undark that Alexx Pons, deputy director of the media relations group at CMS, requested be attributed directly to the agency or a spokesperson noted that hundreds of nursing homes have been audited so far, and approximately half of them “attested to having erroneous schizophrenia diagnoses and committed to correcting their information.”

In reference to the rest of the homes with incorrect schizophrenia diagnoses, the email continued, “we have generally found an absence of comprehensive psychiatric evaluations, medical evaluations, and behavioral documentation to support a diagnosis of schizophrenia.”

Meanwhile, though Nursing Home Care Compare is considered an unbiased source for helping the public make placement decisions for family members, a 2023 study found that facilities will sometimes distort their own reporting, giving them higher quality ratings. The researchers in this case found that schizophrenia diagnoses were in some cases overreported on the MDS to justify antipsychotic therapy when it wasn’t warranted.

And in other cases, Medicare reimbursement claims were filed for antipsychotic treatments that were never documented on the MDS at all. Facilities engaging in that practice get paid for providing the treatment, but the public is deceived into thinking its antipsychotic drugging rate is better than it really is. Only 87 percent of antipsychotic reimbursement claims filed by nursing homes between January 2018 and December 2019 were also “showing up in the MDS,” said David Grabowski, a health care policy specialist at Harvard Medical School who co-authored the study. “And this suggests that the measure that’s being reported on Nursing Home Care Compare is inaccurate.”

Evans emphasized that the greatest barriers to limiting antipsychotic abuses in nursing homes are cultural. The practice continues, he said, in part because it’s so difficult to convince people that what they’ve been doing for years is wrong. “There’s a culture of prescribing, there’s an over-reliance on medication, and an under-appreciation of the risk,” he said. Wehry agreed, adding that most experts in the field now view agitation and aggression less as neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia than as forms of communication.

“There’s a culture of prescribing, there’s an over-reliance on medication, and an under-appreciation of the risk.”

Wasserman pointed out that nursing home residents might lash out aggressively if they feel their personal space is being invaded. “I’ve been hit twice by residents with Alzheimer’s,” he said. The patients “didn’t remember me, and so I got too close to them. I was in their space and they punched me. That didn’t necessitate an antipsychotic medication.”

The response to aggression, Wehry added in an email, is a short time-out. Every good certified nursing assistant “has learned mercy of dementia,” she said. “If you stop whatever has caused the person to strike out, offer reassurance and go away, you can return 5 minutes later and a new approach may work as the person with dementia has no recall of the event.”

Wehry suggested that antipsychotic drugging rates on the order of 3 to 4 percent in nursing homes “would be commensurate with actual clinical conditions.” But while antipsychotics are the big offenders, she said, nursing homes should also strive systematically to cut back on other drugs. Some nursing home residents are on up to 20 drugs simultaneously, she said, “which means that most of their interactions with nursing staff or medication techs is getting them to take a handful of pills, at least one of which is going to make them sick to their stomach. It’s a hell of a way to live and it’s a hell of a way for staff to have to have a job where three times a day they’re trying to get people to take things they don’t really want and make them feel worse.”

“Now, do they need some of them? Sure,” she added. “Do people need as many as they’re taking? Probably not. We could do a whole lot better.”

I saw this personally as my sister was in a Beaver County nursing home due to problems with a neighbor when she lived with me for a year. On day on, Psych 360 was prescribing these drugs and over a year and five months until her death (1/23/25) she lived in fear with numerous falls and injuries and no medical care for her. I went in 5-6 days a week for two hours at lunch time and could not believe what I saw every day. That place was absolutely horrible but the PA Health Dept didn’t seem to see anything wrong with the lace of care for these people. I wrote CMS and sent list of problems and pictures but no response from them either. It was like I was living a nightmare for all that time. I was actually told on several occasions that using antipsychotics is more necessary to control behaviors than giving proper medical care for pain and other medical problems. Staff did not care what these people go through every day. Everyone in Congress and top officials should need to spend at least 2 hours a day for a year before funding is voted on for these lockdown units just like prisons. My sister smoked cigarettes for over 55 years and her doctors were amazed that she had no lung or other problems but a nursing home killed her in one year and five months.

I worked as an Occupational Therapist (& 1 year as an Activity Director.) in many nursing homes. One nursing home automatically put a person on anti depressives the day they arrive to stay.

So wrong to me.

The doctor said it kept them from getting into depression and therfore kept them healthier.

Medication with Seniors acts differently.