The project was so secret, most members of Congress didn’t even know it existed.

In 1942, when an elite team of physicists set out to produce an atomic bomb, military leaders took elaborate steps to conceal their activities from the American public and lawmakers.

There were good reasons, of course, to keep a wartime weapons development project under wraps. (Unsuccessfully: Soviet spies learned about the bomb before most members of Congress.) But the result was striking: In the world’s flagship democracy, a society-redefining project took place, for about three years, without the knowledge or consent of the public or their elected representatives.

After the war, one official described the Manhattan Project as “a separate state” with “a peculiar sovereignty, one that could bring about the end, peacefully or violently, of all other sovereignties.”

Today’s cousins to the Manhattan Project — scientific research with the potential, however small, to cause a global catastrophe — seem to be proceeding more openly. But, in many cases, the public still has little opportunity to consent to the march of scientific progress.

Which specific experiments are safe, and which are not? What are acceptable levels of risk? And is there science that simply should never be done? Such decisions are arguably among the most politically consequential of our time. But they are often made behind closed doors, by small groups of scientists, executives, or bureaucrats.

In some cases, critics say, the simple decision to do the research at all — no matter how low-risk a given experiment may be — advances the field toward riskier horizons.

In the text and graphics that follow, we attempt to illuminate some of the key people who are currently entrusted with making these weighty decisions in three fields: pathogen research, artificial intelligence, and solar geoengineering. Identifying such decision makers is necessarily a subjective exercise. Many names are surely missing; others will change with the incoming administration of Donald Trump. And in every field, decisions are rarely made in isolation by any one person or even small group of persons, but as a distributed process involving varying layers of input from formal and informal advisers, committees, working groups, appointees, and executives.

The extent of oversight also varies across disciplines, both domestically and across the globe, with pathogen research being much more regulated than the more emergent fields of AI and geoengineering. For AI and pathogen research, our focus is limited to the United States — reflecting both a need to limit the scope of our reporting, and the degree to which American science currently leads the world in both fields, even as it faces stiff competition on AI from China.

With those caveats in mind, we offer a sampling — illustrative but by no means comprehensive — of people who are part of the decision-making chain in each category as of late 2024. Taken as a whole, they appear to be a deeply unrepresentative group — one disproportionately White, male, and drawn from the professional class. In some cases, they occupy the top tiers of business or government. In others, they are members of lesser-known organizational structures — and in still others, the identities of key players remain entirely unknown.

Pathogen Research

Most research with dangerous bacteria and viruses poses little risk to the public. But some experiments, often called gain-of-function work, involve engineering pathogens in ways that may make them better at infecting and harming human beings.

The scientists who do this work say their goal is to learn how to prevent and fight future pandemics. But, for a portion of such experiments, an accidental lab leak could have global repercussions.

Today, many experts are convinced that Covid-19 jumped from an animal to a person — and most evidence collected to date points squarely in that direction. Still, some scientists and U.S. government analysts believe that the Covid-19 pandemic may have originated at a Chinese laboratory that received U.S. funding

Whatever the reality, the possibility of a lab leak has heightened public awareness of risky pathogen research.

Unlike some other fields of risky science, scientists working with pathogens in the U.S. typically receive oversight from a mix of institutional committees and civil servants — with a few lawmakers currently lobbying for additional regulatory levers.

Congress has never passed regulations placing specific limits on gain-of-function research. A handful of legislators — some of whom are now retiring — have led recent efforts to investigate gain-of-function research and develop new regulations overseeing it.

For now, various officials at the White House and within the Department of Health and Human Services are responsible for crafting and implementing the policies that govern most pathogen research. Pictured below are some of the people who either perform that work, or oversee teams who do.

A lot is murky about this process. In interviews, biosafety experts — including some current and former government officials — admitted to having limited understanding of the HHS’s internal processes. It’s also hard to know for sure what unfolds outside the auspices of HHS, in private-sector labs that aren’t covered by existing regulations.

Two secretive committees — the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Dual-Use Research of Concern/P3CO Committee and the HHS P3CO Review Group — make key decisions on whether proposed experiments are likely to make pathogens more dangerous, and, if so, whether they should proceed. Committee members and chairpersons are anonymous, and it’s unclear how many people serve on them.

Some scientists say this oversight isn’t robust enough, and that for some key decisions, researchers and institutions largely police themselves.

This policing function is largely done by a body called the Institutional Biosafety Committee, composed mostly of scientists, that makes basic calls about whether research is safe or not. The individuals pictured below chair the IBCs for the handful of U.S. institutions that house the highest-security-level laboratories, or that have a track record of research that involves manipulating pandemic pathogens.

While the groups above are necessarily incomplete, the individuals presented here do occupy key positions in the overall apparatus overseeing pathogen research in the U.S. These decisions can have far-reaching consequences — even if very few Americans know who is making them.

One of the secretive committees that makes decisions about potential gain-of-function research is housed with the National Institutes of Health. The other is part of the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response within HHS. Spokespeople for both offices declined to share details about the committees’ memberships, or even to specify which senior officials coordinate and oversee the committees’ activities.

“I think some of this is for good reason, like preserving the scientific integrity and protecting science from political interference,” said one former federal official who worked outside of HHS, in response to a question about why details about oversight are often difficult to pin down. (The official spoke on condition of anonymity because the views expressed may not reflect those of their current employer.) “I think some of this is also driven by an inability of HHS to understand how to navigate increasing public scrutiny of this kind of work,” the official added, describing the lack of transparency around the special HHS review panel as “totally crazy.”

Artificial Intelligence

If pathogen research is mostly funded and overseen by government agencies, AI is the opposite — a massive societal shift that is, in recent years, led by the private sector.

The consequences of the technology are already far-reaching: Automated processes have denied people housing and health care coverage, sometimes in error. Facial recognition algorithms have falsely tagged women and people of color as shoplifters. AI systems have also been used to generate nonconsensual sexual imagery.

Other risks are hard to predict. For years, some experts have warned that a hyperintelligent AI could pose profound risks to society — harming human beings, supercharging warfare, or even leading to human extinction. Last year, a group of roughly 300 AI luminaries issued a one-sentence warning: “Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

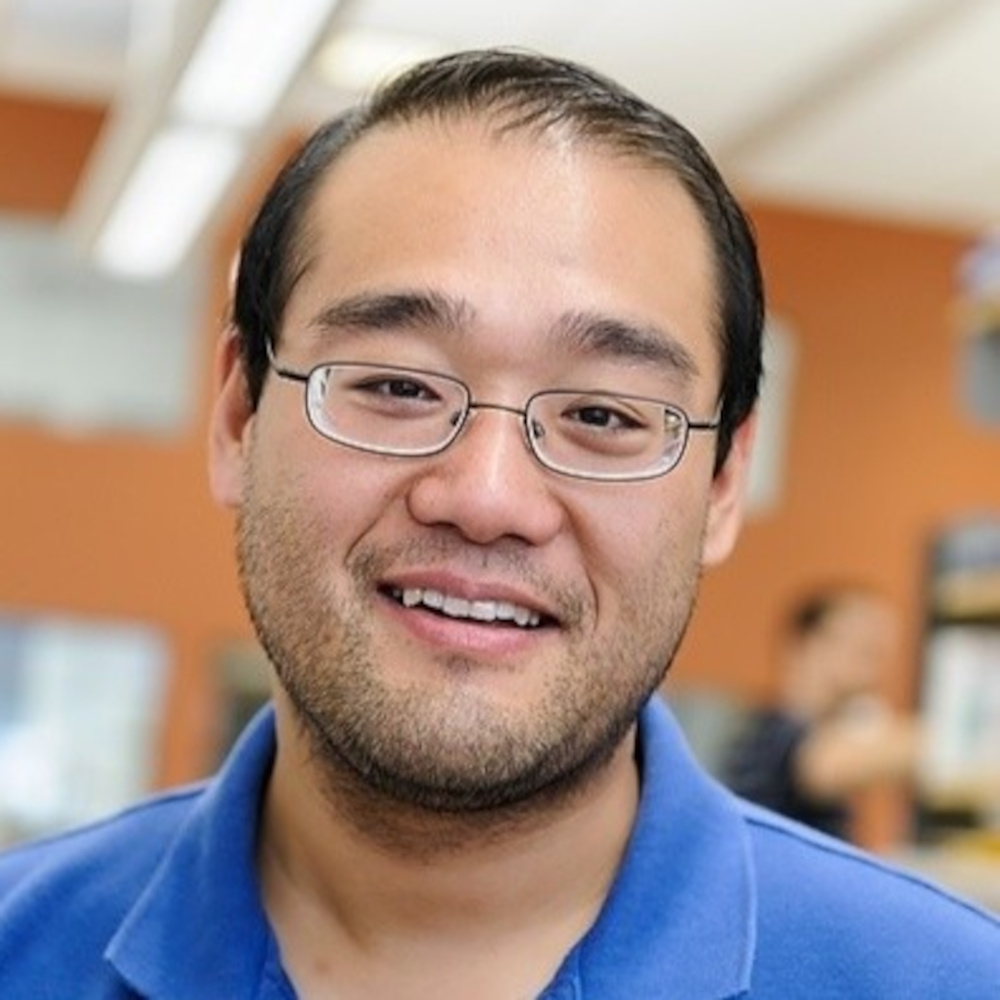

Many other experts, especially in academia, characterize those kinds of warnings principally as a marketing stunt, intended to deflect concern from the technology’s more immediate consequences. “The very same people who are making and profiting by AI are the ones who are trying to sell us on an existential threat,” said Ryan Calo, a co-founder of the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public.

“It’s cheaper to guard against existential threat that is future speculative,” he said, “than it is to actually solve the problems that AI is creating today.”

Despite calls for regulatory scrutiny, no federal agency comparable to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration conducts pre-market approval for AI systems, requiring developers to prove the safety and efficacy of their product prior to use.

Federal regulatory agencies have made limited moves to oversee specific applications of the technology, such as when the Federal Trade Commission banned Rite Aid from using face-recognition software for five years. At the state level, California’s governor recently vetoed a controversial bill that may have curbed the tech’s development.

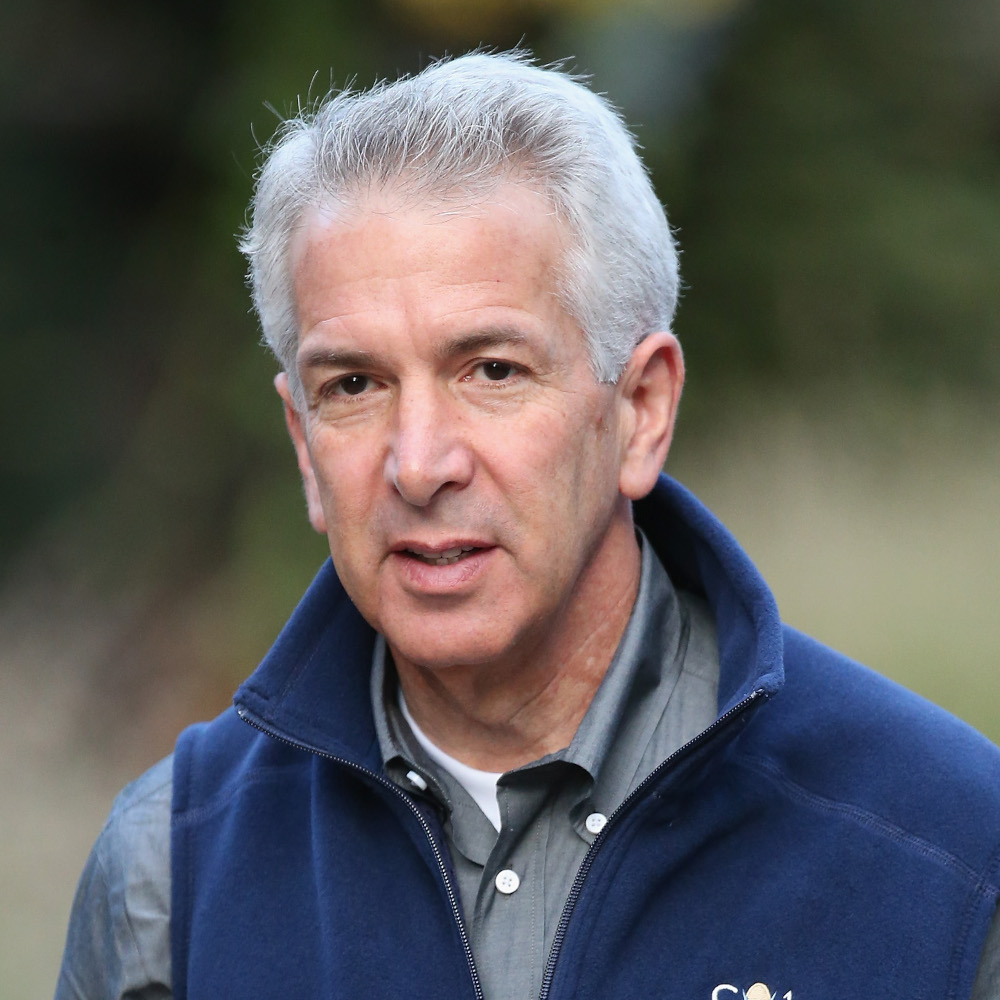

The power to assess the varying risks of AI — and to decide whether they’re worth taking — largely rests with a handful of U.S.-based companies. Their AI research is mostly bound only by a patchwork of voluntary guidelines and principles.

Not every company may send the release of new models all the way up the chain of command to the CEO. And there are researchers, internal safety employees, board members, and others involved at various stages of AI development. But ultimately, in 2024, the decision-making power lies with those at the top of the companies leading the field, shown below.

Solar Geoengineering

In theory, injecting particles into the atmosphere could reflect sunlight, cooling the planet and reversing some of the worst effects of climate change. So could altering clouds over the ocean so that they reflect more light.

In practice, critics say, solar geoengineering could also bring harms, both directly (for example, by changing rainfall patterns) or indirectly (by sapping resources from more fundamental climate solutions like reducing greenhouse gas emissions.) And once interventions are underway, they may be difficult or dangerous to stop.

Right now, the science on geoengineering largely consists of computer models and a handful of small-scale tests. But in 2022, worried about where the field was trending, hundreds of scientists and activists called for a moratorium on most research. Some experts suggest that even small, harmless real-world tests are paving the way for future, riskier interventions.

Within the U.S., no single government agency exercises clear-cut control over the decision of whether to test or use that technology, although certain outdoor experiments could plausibly trigger regulators’ attention — for example, if they affect endangered species. Globally, experts say, it remains unclear how existing international treaties or agencies could limit solar geoengineering, which could allow a single country or company to unilaterally alter the global climate.

Absent independent oversight, the decision makers on any given geoengineering experiment are “pretty much the people who want to do it, and the people who are on the very closest front lines to it,” said Tracy Hester, an environmental law expert at the University of Houston.

Key decision makers include research funders, startup founders, and the handful of scientists trying to pilot these technologies in the real world.

A large portion of funding for solar geoengineering research comes from philanthropies, not governments. Pictured below are some of the most influential funders.

Governments are getting involved, too. The United Kingdom’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency recently announced a major new funding program for solar geoengineeering research. And in 2020, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, under instructions from Congress, launched an initiative to explore potential solar geoengineering projects.

Some of the key agency decision makers are shown below.

A handful of academic groups are leading the study of geoengineering. Pictured below are researchers who have made efforts to perform real-world tests, and others involved in high-level policy conversations about the future of solar geoengineering.

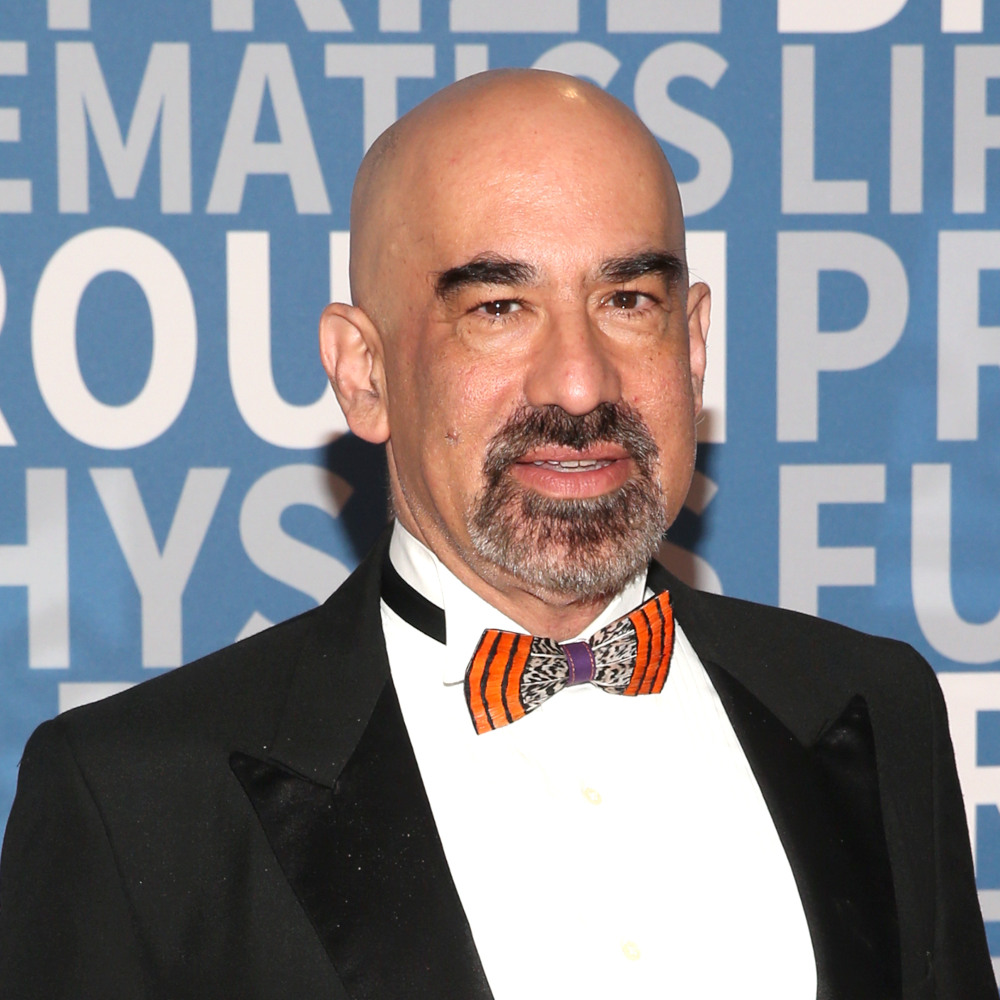

Two private companies are also publicly pursuing solar geoengineering, including conducting real-world tests. Some experts describe Make Sunsets, a startup, as a kind of stunt. But they’re watching the Israeli-American company Stardust Solutions closely — especially after it reportedly raised $15 million in funding, with support from a prominent venture capital firm, Awz Ventures.

Solar geoengineering remains in its early stages. The question is whether these decisionmakers are nudging the world toward a more dangerous future — or laying the groundwork to fend off the worst of climate change.

“It’s a very small group of people” making decisions about solar geoengineering, said Shuchi Talati, founder of the Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering. “It’s a very elite space.”

UPDATE: A previous version of this piece stated that NOAA launched an initiative in 2020 to explore potential solar geoengineering projects. The agency is currently exploring the science needed to assess the potential benefits and risks of solar geoengineering.

Michael Schulson is a contributing editor for Undark. His work has also been published by Aeon, NPR, Pacific Standard, Scientific American, Slate, and Wired, among other publications.

Peter Andrey Smith is a senior contributor at Undark. His stories have also been featured in Science, STAT, The New York Times, and WNYC Radiolab.

Visuals: Public domain (Peters, Paul, Marshall, McMorris Rodgers, Wenstrup, Young, Jorgenson, Taniewski, Singer, O’Connell, Becerra, Bertagnolli, Marrazzo, Erbelding, Sundaram, Prabhakar, Stevens, Priola, Frost, Breeze, Spinrad); Getty Images (Special committees, Pitt, Amodei, Altman, Zuckerberg, Pichai, Doherty, Lockley, Setiya, Simons, Spergel, Tschinkel, Krupp, Cohler); World Economic Forum/Flickr (Nadella); Lisi Wolf/Wikimedia Commons (Jassy); Other public sources (Levinson, Ison, Gastfriend, Cyr, Suen, Trick, Ingalls, Simon, Weaver, Hayhurst, Field, Keith, Mengis, Visioni, Harrison, Wood, Skinner, Ayers, De Temmerman, Schroepfer, Dilling, Birenbaum, Verhalen, Schwartz, Pritzker, Parker, Wanser, Symes, Gur, Seddon, Iseman, Song, Yedvab, Ashkenazi)