On Highway Noise Barriers, the Science Is Mixed. Are There Alternatives?

Drive down the interstate highways bisecting many busy cities and suburbs, and you’ll likely no longer see the homes, buildings, or vistas that used to be a staple of roadway views. That’s because in most populated places, massive sound walls have been installed. These noise barriers, typically made of concrete and standing an average of 14 feet, turn the backs of neighborhoods into prison-like yards, and, on narrower stretches of road, encase drivers in roofless tunnels. Since the 1970s, when the barriers first started sprouting, nearly three thousand linear miles have been erected. According to Department of Transportation officials, California alone has 760 miles of sound walls; Florida, 252 miles.

By and large, residents say they want these walls. California has a waiting list for them. And at meeting last June with representatives of the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT), which this journalist attended, many residents of Boca Raton were eager to know whether sound walls would be erected to buffer their homes from a planned turnpike expansion.

One man’s concern, however, stood out at that meeting. He talked about his prior house, which he claimed was quiet until a highway noise wall was installed a few blocks away — and it turns out that this isn’t so unusual. For homes several streets from the barriers, or for those uphill of sound walls — and for everyone in certain weather conditions — the walls don’t effectively block the sound, and may even help to amplify it. And what’s worse is that these aren’t new insights. Engineers and acousticians have known for years that the sound barriers bracketing America’s urban and suburban highways are only marginally useful, and that a variety of better technologies could be developed.

The problem: Nobody has an incentive to get them on the road.

“Walls are not a very effective solution,” said Robert Bernhard, vice president for research at the University of Notre Dame and an expert on noise control. Because the federal government pays for noise walls — and only noise walls — as part of highway expansion projects, he said, there is little incentive for researchers to keep testing and perfecting the alternatives.

Noise that bothers a community must be at least considered for mitigation thanks to the Noise Control Act of 1972. It was passed as part of the federal government’s efforts to better protect the environment — noise being one of many pollutants coming under scrutiny. Typically, when an interstate is widened or newly built, and in a small number of cases, when no additional construction is done, the state highway agencies determine whether they should mitigate the ruckus to area neighborhoods.

That ruckus tends to come from three separate elements: the roar of the vehicles — primarily the exhaust and engine; the whooshing aerodynamics around the vehicles; and the slapping of the tires against the road. At highway speeds, the predominant sound for cars is that of tire-pavement; for trucks, engine and stack sounds are also a factor — at least for now.

States use a specific noise model to predict the sound once the road will be expanded, and for several decades after. The complex formula includes the mixture of cars and trucks expected on the road; the buildings and vegetation in the area that would block some sound; the configuration and ground quality of the land between the road and the homes; the ways the sound is expected to diffract around the wall; and other key factors.

Based on the formula, if the noise is projected to go over the government threshold of approximately 67 decibels (dB) during the noisiest hour of the day — and it is “reasonable and feasible” to reduce it at least 5 dB for some percentage of homes — the government requires that walls be included if the surrounding community wants them. Just what constitutes “reasonable,” of course, is interpreted in different ways by each state, which is why the use of sound walls varies greatly from one state to another.

Even with the sound reduction, however, roadside residents are unlikely to hear crickets chirping. A dishwasher running in the next room is 50 dB, as are the ambient sounds of a laid-back city. The noise criteria aim to allow people to talk over their backyard picnic table, or shout at someone several feet away. “It’s not a situation where meeting the standard makes for a great backyard environment,” Bernhard said.

Of course, some of our ability to process sound is psychological: If people can see the tops of trucks over the wall they say it’s noisier, something people in the field call “psycho-coustics,” explained Bruce Rymer, a senior engineer at the California Department of Transportation. Just by ensuring a wall breaks that line of sight, “we achieve a reduction of 5 decibels,” said Mariano Berrios, environmental programs coordinator at FDOT.

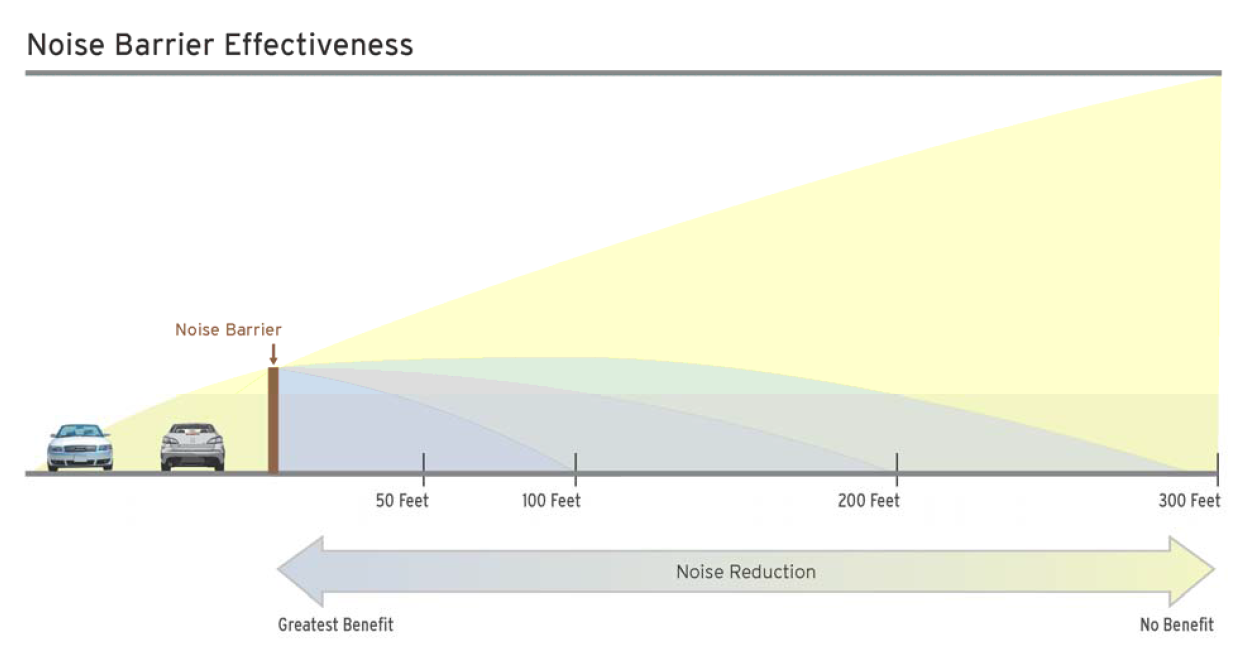

But because noise travels in waves, not straight lines, sounds can and do go over the walls. This is why even with barriers standing 16 feet, homes several blocks away can hear the highway. Part of the sound wave is absorbed, part is reflected away from the wall, and part is transmitted through, Berrios explained. “Most of it goes above the barrier and gets diffracted, and gets to the receiver,” — that is, to a resident’s ears — he said.

This is especially problematic during certain weather conditions. When the consulting firm Bowlby & Associates, in Franklin, Tennessee, measured sounds around a highway in a yet-to-be-published study, they found that residents hundreds of feet from the highway could hear sounds some 5 decibels louder if the wind was blowing towards them, said Darlene D. Reiter, the firm’s president.

Weather, however, isn’t taken into account by the regulations. The noise model “assumes neutral conditions — no wind and no temperature effects — when in reality that happens only occasionally,” Reiter said. In the early morning, if the ground is cool but the air warms up, for instance, sound that would normally be pushed up is refracted downward, causing homes some 500 or 1,000 feet from the road to hear it loudly.

Those living up on hills or near freeway openings sometimes find the noise actually worsens once walls are built nearby. It was a gap in the barrier near his suburban New Orleans home — partially to accommodate a highway exit — that substantially increased noise in the backyard of attorney Harry Molaison. Although his house is roughly 500 feet from the service road leading to the interstate, “you have all this rebounding sound from one parallel wall to another,” he said.

“We don’t have the same peacefulness we had before,” he added.

It’s with these problems in mind that the University of Pittsburgh recently received a grant to study whether walls could be made of materials that absorb, rather than reflect, more of the noise. But even if new materials were developed — in addition to the popular concrete, sound walls are currently made of everything from masonry and steel to wood and plastic — the question would remain: Is this the best use of taxpayer money?

Highway walls are expensive, running more than $2 million per linear mile — for one side of the highway, Rymer said. The total spent on sound walls through 2013, the most recent government figures, tops $6 billion. Each state has a different threshold for what triggers the need for a “reasonable” intervention. According to Rymer, in California, which has one of the lowest thresholds, walls are justified when they cost federal taxpayers as much as $92,000 per impacted home. This is money that isn’t spent on mass transit, or fixing ailing tunnels or bridges, or other transportation needs.

“Three miles of sound barriers on both sides of an interstate would buy another M8 railcar for Metro-North [train service], and take 100 passengers off the state’s highways” wrote Jim Cameron, the founder of a Connecticut-based commuter advocacy group, in a newspaper editorial earlier this year.

Mammoth barriers also block small animals — frogs, turtles, snakes — from getting from one habitat to another, said Elizabeth Deakin, professor emerita of city and regional planning at the University of California, Berkeley. This may affect wildlife communication, migration, and even reproduction.

Of course, it’s understandable why neighbors whose homes border a highway want something that mitigates the noise. Loud traffic interferes with the enjoyment of your yard. Having cars so close to a home can even cause health issues. According to a 2011 World Health Organization report, environmental noise leads to heart disease, hypertension, and cognitive impairment in kids. But if the bulk of the noise is caused by the tires and the roadway, some experts suggest that attacking the commotion at the source — or testing other methods that might absorb it — could be a more effective and less costly approach.

Some tire companies have done research on making tires quieter, but the bulk of their efforts are in keeping the noise from penetrating the inside of the car, not in silencing them outside, Bernhard said. And while electric cars are far quieter than cars with internal combustion engines, at highway speeds car engines aren’t much of a factor — though trucks could be a different story. Tesla’s recent introduction of its electric semi-truck will undoubtedly alter highway sounds going forward, since the engine and stack noises will be eliminated.

Companies in some European countries are experimenting with unconventional methods that could ultimately block highway sound. One, a luminescent solar concentrator (LSC), features colorful translucent sheets that not only don’t obstruct views and sunlight, they generate electricity to nearby homes. Another is researching whether dense bamboo or other plant species can be coaxed to form an effective vegetation wall.

But altering the pavement is where most of the potential seems to lie. Several states — Arizona, California, and Florida in particular — have experimented with such changes. These “quieter pavements” involve adding more porous surfaces to asphalt or altering the configuration of the tiny grooves in concrete. “When there is texture on the surface of the pavement, the trapped air inside the tire’s tread pattern doesn’t make the same clapping noise,” Bernhard explained.

Some states have laid thousands of miles of these road surfaces, and have seen results of up to a 9dB reduction in noise. Dana M. Lodico, a senior consultant with Illingworth and Rodkin, said engineers have been studying its effects since the 1990s. Her firm alone conducted four major decade-long studies and many shorter ones. “There’s tons of research” showing its effectiveness, she said, especially in states with warmer climates. (The studded tires some drivers use in snowy states can break down the road surface more quickly.) One major report that her firm worked on examined the cost-benefit of sound walls versus pavement changes, and found many scenarios where a combination of lower walls — or no walls — were more effective and less expensive than a barrier by itself, she said.

Despite all of these potential innovations, however, the current structure of federal highway subsidies is likely to keep them from widespread use anytime soon. As it stands, the Federal Highway Administration has not approved pavement as an accepted form of noise abatement. “We have uncertainty about how long the reduced noise level from the pavement will last, and there is no guarantee that the reduction can be achieved on a consistent basis nationwide,” said agency spokesperson Doug Hecox.

That means states that currently change their pavement still have to put up walls as part of their highway projects. And because maintenance of the pavement to keep it quiet — resurfacing perhaps every 15 years, Lodico said — would fall to the states, many state officials undoubtedly prefer the more-permanent walls, which are built almost exclusively with federal funds.

When it comes to mitigating highway noise, Bernhard noted, “The predominant culture is cost avoidance.”

Meryl Davids Landau is a Florida-based journalist whose work has appeared in a variety of publications, including U.S. News & World Report, Glamour, Vice Media, Parents, Reader’s Digest, Good Housekeeping, and Prevention, among others.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

how can you learn this

I am ok withe the existing traffic noise on the road bedbut,the overpasses that traverse swann,Morrison,Jetton ect on down to Himes , are far more problematic. If the barriers were erected 30 ft. beyond each lower roadway the offendig screams and air pressur growls would be muffled.

How to argue for only 2 residences on highway. They were there when road had no shoulder. Just country road. Now project lane to be 6 lane

I live in MN. They added a third lane to the western portion of the interstate that rings the Minneapolis/St. Paul metro area. They added sound barriers everywhere, except my side of the freeway adjacent to my neighborhood. What happened is now that there’s a barrier on the far side of the freeway, the noise bounces off and comes back significantly louder on my side. We can’t even hear our TV during rush hour! Sometimes, when the wind is just right (out of the southwest), we have to close our south-facing bedroom window (in the summer) because it sounds like the traffic is driving right through our bedroom! Even with the windows closed, like they are 9 months out of the year, the freeway noise inside my house is very noticeable. I live for those very rare days when the wind is out of the east or northeast. We do have trees planted on the west side of our house (and no windows at all on that entire side), but again, about 9 months out of the year there are no leaves on them. The reason we were given for there being no abatement in the small section of our side of the freeway was absolutely cost-driven: “There aren’t enough houses in this section to justify it.” Well, guess what? Now there are, as developers have been adding houses like crazy. However, they won’t build a sound barrier here for at least 40 years because that will be the next time they do any major work on the freeway again. It’s always a case of “kick the can down the road”, and we’ll be dead by that time as we’re in our mid-50s. Our only solution at this point is simply to sell our house and move.

Who do I contact to have the noise levels checked in my backyard? They have expanded the highway that runs behind my house a few miles down, but not the part that is in my back yard so we didn’t get the walls. We love to have someone check this out.

I do not want a wall in my backyard. Now I am surrounded by a high grey wall as though I am a prisoner in jail. PLANT TREES, BUSHES. BAMBOO. Vegatation cleans the air, absorbs noise, beautifies the roadwsy, helps break up strong winds, attracts birds. Bees, butterflies, provides privacy and security to those residents whose backyards abut the highway.

Sounds like a win-win solution to me

.

Same problem as others have stated, I regret buying a home along a highway, techically a new york parkway. great article but you did not mention dirt berms as a barrier, also what about speed. the 55 mph speed limit is a joke here in new york. Also as someone stated, screaming motorcycles and racing cars that think it is their private drag strip.

I bought a manufactured home a BEAUTIFUL 2006 one built high above the ground. The home is surrounded by very loud road noises, Florida Turnpike, Boca Reo Road and Glades Road all very loud roads with a lot of traffic.

I have lived here for over two years and can’t even sit on my patio because of the loud noise When I first looked at the home it must have been on a quite road day hardly any noise but, after I bought the home and moved in I noticed the loud noise every day and even during the night when I was supposed to be sleeping the sound was terrible, I tried to tune the road sounds out but, it was very hard.

The main reason why I am posting this is because for the past two weeks I have started to hear loud noises in my right ear. At first I was very scared and nervous but, now I try to cope with it. Like now typing this post I am hearing a roaring in my ear. It usually last for a while — maybe an hour — then it gets lower to a hiss and that gives me some relief. I have experienced this 3 times in two weeks so far. Hoping that it wouldn’t come back again when it leaves. It gives me a very stuffy feeling in my head and ears but I can cope with that. But not that loud roaring noise that I didn’t have when I moved here. My ears were perfect. I believe the loud road noises did this to my ears and caused me to get tinnitus.

Just wanted to post this so readers would know. Maybe if you are thinking of buying a home around a lot of road noises think twice before you buy it.

Thank you for reading my post and please pray for me that my tinnitus gets better. Thank you all and have a blessed day, Laurie.

Stop building interstates and highways through neighborhoods. Kinda seems obvious to me.

Here’s a question: If, as seems according to the illustration of a sound wall and noise at the top of this article, sound travels in waves and like water will flow over or around a barrier, would it make a barrier wall more effective if the top of the wall curved over toward the highway – like a wave beginning to crest? Would that redirect flowing sound back onto the road, thereby reducing even more, the amount of sound that makes it over the top? Just a thought.

I would think a curved (towards traffic) topper could be a helpful design feature. We have a proposed large high density /high intensity of uses commercial/residential project at 56-ft high building next to many 9-12 foot tall manufactured homes, with a new 2-lane roadway to serve the project to be 3-ft from our homes that line the perimeter’s 2 shared fencelines. It was the building’s stories on the 2nd through 5 levels swinging out at an angle towards the fenceline that gave rise to concern about amplifying noise, that 1/2 pipe effect. Its similar to the curved simple attachment that can be bought (vs. a sound bar) to redirect sound from down or back facing speakers in new TV’s to redirect sound back towards the front where the screen is (a speaker design change that of course serves the need to buy a sound bar). We are pursuing with the developer a sound wall idea (its not fullproof) along with noise-absorbing materials on the 15-ft tall ground floor of the building and roadway materials to help absorb sound from all uses. We’ll see how far we get with those ideas (developers want maximum profits, even with the added density bonuses giving up to 35% more market rate units = higher profits, regardless of local laws).

Hello Mr. Huber – Your idea about the bamboo wall is very interesting and certainly cost effective when compared to construction type solutions. I work in hoa management and I know that it can be frustrating when trying to get a board to agree to a beneficial solution for their property but they just don’t have the vision. I offer the following suggestions that might be persuasive: 1) plant a smaller area as a test site that residents can visit and experience the noise reduction and see how the actual plants will look, move, smell – the full sensory experience; 2) an artist rendering of what the final product will look like when fully grown; 3) the focus is on noise reduction but don’t forget to include how attractive the new view will be of a bamboo forest at the end of the lake – certainly more attractive than a highway; 4) community security will be enhanced as no one is going to penetrate that forest to commit petty crimes or vandalism and then get quickly away on the highway; 5) highway trash and whatever else the wind blows off the road — sand, soot, exhaust, anything that falls off the back of an overloaded truck, etc will not wind up in the lake or along that berm that is the community’s property; 6) is there a state or federal tax deduction or grant money to be had for putting that strip of land to good use? I am sure that right now, when that land is not used at all (because it is along the highway) the community is still paying taxes on it and possibly having the cost of maintenance i.e. mowing at the very least; how long would it take for the cost of the taxes to outweigh the cost of the bamboo wall? 7) scientific studies are useful but local experience is often more persuasive; look for communities around you who have used bamboo for various purposes such as noise reduction, privacy, security, graffiti prevention, etc and get their testimonies, print them up, mail them out, invite them to speak at a meeting; if any local colleges (including community colleges) have Environmental Science, Engineering, Construction Management or other related degrees, make your offer of a study site as in your letter above, directly to those dept chairs. It is a unique and useful opportunity and could be a draw for the college as well for new students interested in those programs of study; 8) and finally, give it time – resolution in hoas doesn’t grow as fast as bamboo – often the same topic has to be presented multiple times with possible new info added each time; boards change, circumstances change, and then one day an idea formerly rejected sounds like a good and reasonable — and cost effective — solution. Soldier on! It all begins with one true believer – and that is you!

The answer to provide sound absorbtion to already existing and new concrete walls is….. Wait, let me go buy stock in this product first…..ok.. spray urethane foam..2″ layer on traffic side of wall. Cheap and will do the job.

Thanks for sharing. Barrier Walls are by far the most effective airport noise barriers and noise abatement solution available.

Im the past president of the noise abatement committee for a community in Punta Gorda Florida. Our neighborhood was a quiet community abutting I-75 until 2 years ago. 2 years ago the highway Lane widths were increased by two lanes.Fdot.and their wisdom decided to erect a sound barrier 22 ft tall on the opposite side of the highway. Sadly the community across the highway which received the sound barrier is also experiencing elevated noise further into the community due to environmental factors which primarily are wind and humidity

Today our community is experiencing an unreasonable increase in sound levels due to noise barrier reflection into our community . Atmospheric conditions ;wind ; humidity and the existence of a lake which goes right down to the highway acts as a vector for the noise to travel up through the neighborhood. Our community and committee have been in contact with Fdot for numerous years. We have spoken to them using EPA policy and fdot Policy to try to find a resolution to this problem. Unfortunately we do not fall within the reasonableness category due to the lack of housing at the highway. However we do present one very unique situation which many neighborhoods would like to be in. Our H O A owns a strip of land 40 ft deep directly behind where a sound barrier would have been erected to protect our community. This 40-foot strip is one mile long. Our committee has also come to the conclusion and understanding that erecting a concrete sound barrier on our side of the highway would only reflect more noise up into the air ;broadcast by environmental factors wind and humidity and would be detrimental for both communities on the highway. We have proposed to plant a bamboo curtain out of bamboo Seabreeze which is extremely dense ;40 ft Deep by 1 mile long. This bamboo grows so thick that after 5 years you cannot put your arm into the Hedge more than 12 in. This specie will grow to a height of 30 ft This bamboo species has multiple inclusions ;extremely dense ;a great amount of twig material and constant Leaf material on the species. We believe that this would definitely decrease the decibel rating on our side of the bamboo curtain. We also believe because the bamboo hedge is regular at the top that the sound wave penetration over the barrier would be slightly disrupted to the benefit of the neighborhood. We also believe that planting the bamboo curtain would benefit our neighbors across the highway and stop reflection of Highway noise into their community

A detailed budget was presented to the ho a board and the final numbers for 1 mile of bamboo curtain was approximately $300,000. Sadly the proposal was voted down 6-0. I understand the reason for this was there are very few scientific studies that would support our beliefs. I am writing this article in Hope that a university or a sdot Research facility would be interested in running a 1-mile by 40 ft wide bamboo curtain test on our site. This would be a truly unique situation in which one side of the highway would have a 22 foot concrete barrier and the other side would have a 30 foot bamboo curtain. I agree with Robert Bernhardt that the solution which we have seen in the United States and other countries that use reflective sound barriers is not the answer to the community as a whole. Please make comments to this article and I believe in climates that support these very dense bamboo Hedges that there is a solution on the horizon for all.

Problem with the Dutch site is that it sends the sound waves UP. That is not absorbing the sound as it preferred and makes the problem worse for anyone just above the wall.

I look forward to electric trucks. Truck engines are a major source of noise. But trucks are necessary to those of us who buy any product other than fruit and vegetables at a farmer’s stand. I saw no mention of another, unnecessary, malicious / narcissistic source of noise: Motorcycles with altered exhausts and automobiles with loud exhausts. Millions are spent on walls and other infrastructure solutions. What we need is for the police to enforce the noise laws, and for our lawmakers to enact common-sense laws. If you can hear a car or motorcycle a half-mile away, it is TOO LOUD. Thank you.

Very well written article on an interesting topic. I’m commenting here to let everyone know there IS a solution to the noise problems outlined in this article. Sound Fighter Systems, a company based out of Shreveport, LA, right here in the USA, is a manufacturer of sound absorptive sound walls and has been in existence since 1972! We do hundreds of sound walls and noise barriers each year throughout the United States. One of our many applications includes work within the transportation sector (Highway/DOT and Rail) noise mitigation. We are an ABSORPTIVE barrier, unlike concrete which is REFLECTIVE. This is an all too often overlooked aspect when it comes time to build these sound walls. I would kindly ask anyone interested in this particular topic to take a look at our website. We take great pride in finding solutions (just like this one) to noise problems that affect people every day.

In regards to everyone’s comments, David Wright has a spot-on explanation as to the reality of the issue with finding a “solution” for these noise problems. The technology exists to achieve a greater noise attenuation in these barriers, (our sound walls are 1.05 NRC and 35 STC). We simply need to implement a new set of standards and expectations that are put in place for these projects. There are certain states that have moved entirely away from reflective sound walls and have replaced ONLY with absorptive. We need to follow their footsteps and change the standard.

Thanks for your interest.

-Toby J. Kuznia

Sound Fighter Systems

This is a Federal job justification program, not a noise solution. As a professional noise engineer working nationally, we reviewed easy upgrades with the State Dept. of Transportation. We were surprised to find that only a single 1/2 page in the 3 inch thick wall specifications manual for bidding and construction address two of the weakest and most misapplied noise metrics in the businessas the fundamental for design – STC 20 and NRC 0.70. When given a formal proposal (patent pending), the two young men responsible for the whole State simply said… “No, just STC 20 and NRC0.70 please.. we wont think of anything else”. A Federal budget sink of gigantic proportion in my opinion, based on experience.

I tend to agree. I work for a state transportation agency (won’t say which one), and while my job has nothing to do with noise barriers, I’ve done voice over work. I’ve often thought that we just aren’t designing the walls correctly. There simply must be better materials – and better “shapes” inside the wall – to more effectively absorb the noise. When you consider the design of the ultra quiet rooms that are out there, it’s obvious that we could do better absorbing highway noise. I still hold out some hope that some research arm of some transportation agency or some university somewhere will pick up this ball and run with it.

We’re facing the sound wall issues here in Maryland with the beltway expansion. You mention the STC and NRC standards, is there anything publicly available that discusses pros / cons of using these, what else to look for? Our state has 6 pre approved sound wall vendors, I know the NRC requirement is 0.8, but we (homeowner’s association) and trying to find out more info. Any help appreciated. Thanks.

I’m sure most people realize that noise is still a problem behind the walls. It’s the privacy and security that people behind the wall want.

If a better way to reduce the sound is available, people will still want the walls between them and the highway. They will just want both.

Plants would work better. Especially large shrubs and trees. See Sr. Project at Cal Poly, SLO. It was mine.

Marijuana plants would do great

Plant ivy at the base of the wall. In a few growing seasons it will be beautiful, resist graffiti, and reduce noise.

4Silence is a solution we developed and being used here in The Netherlands. It benefits people who are living nearby a highway.

I have seen experiments in several parts of the US.

Some walls have individually offset panels, some are wood, some have plants in front of them, some have grooves in them.

I think the problem is complicated near cities because the traffic speed varies considerably. Congestion at different times of day and slowing traffic with adverse weather will affect any resonant frequency.

Any effort to provide vegetation buffers will eventually be reduced when someone wants to widen the road.

I hope the experiments continue and people continue to share the information gathered.

Thanks for your comment.

Is there an English language version of the website link you included in your comment?

In the top right-hand corner of the Dutch site you can see NL and EN – click on EN for an English version.