Ten years ago, Oliver Uberti, then a designer for National Geographic, was given an unusual task: map the travels of Annie, an African elephant, in search of food and water with her calf near Zakouma National Park in Chad. Scientists had radio-collared Annie, and over the next 12 weeks they tracked her movements over 1,000 miles. On August 15, 2006, she stopped moving — killed by poachers.

BOOK REVIEW — “Where the Animals Go: Tracking Wildlife With Technology in 50 Maps and Graphics,” by James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti (W.W. Norton, 192 pages). All maps with this article Copyright © 2017 by James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti, reprinted with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

For Uberti, making the map provoked an “irreversible” shift in his consciousness. A decade later, he still looks at it and sees not just an animal but a story, emblematic of the thousands of elephants killed by poachers in Zakouma and the tens of thousands across the African continent.

Now Uberti has joined with James Cheshire, a geographer at University College London, to create “Where the Animals Go,” a collection of 50 maps and graphics of journeys by animals, from European badgers to gray-headed albatrosses. Part coffee-table album, part scientific research compendium, the book presents these global perambulations in lush detail, reveling in their minutiae and in the technological leaps that make such observations possible — what the authors call “a new kind of footprint.”

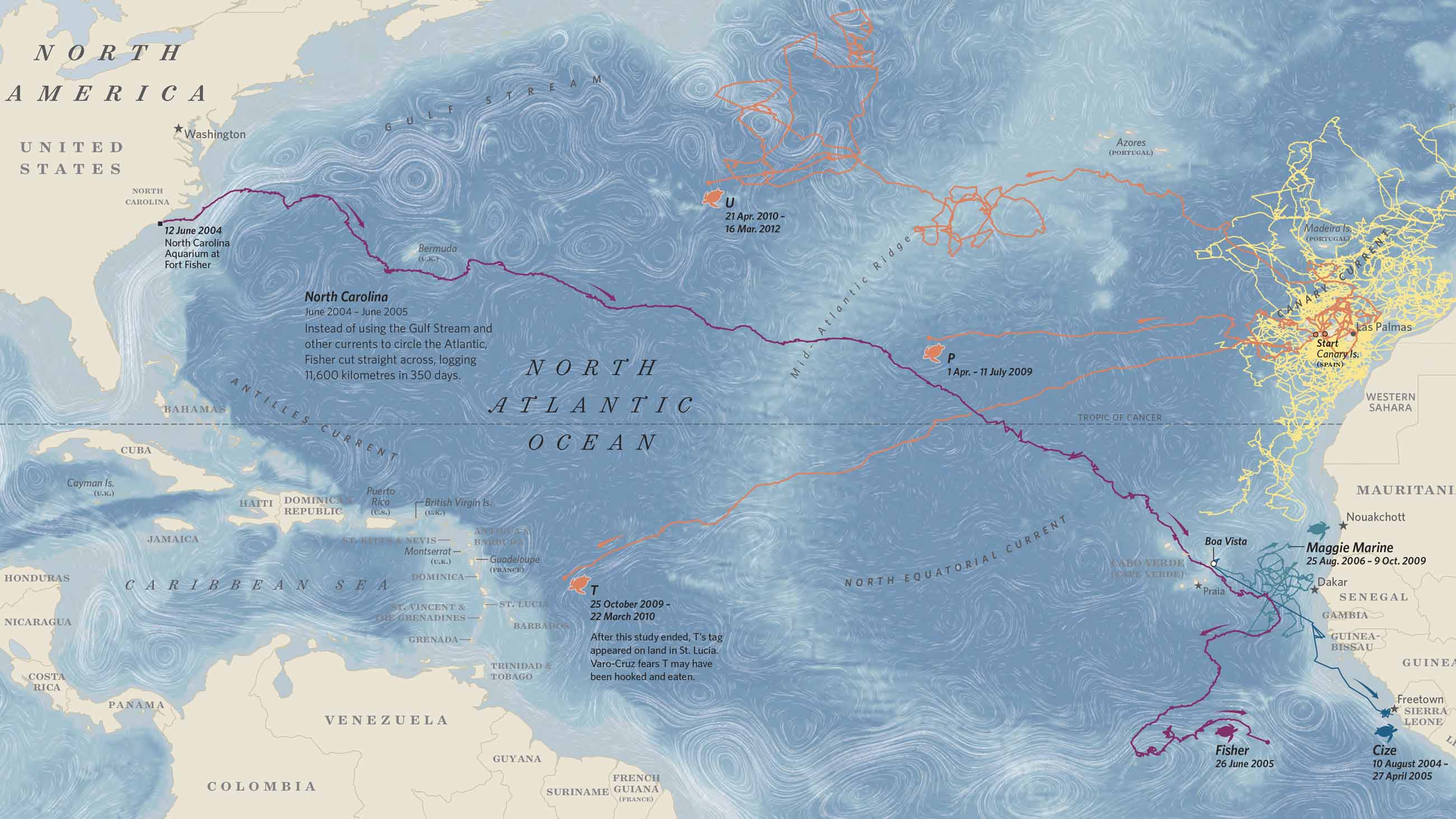

Some of the most compelling maps depict extraordinarily epic pilgrimages: the pathway of the Arctic tern that flew more than 40,000 miles from the Arctic to Antarctica and back again, far longer than a nonstop commercial jet can go. Readers can swim alongside humpback whales that appear to travel to majestic mountains deep underwater, or trace the adventure of a single loggerhead turtle who traveled 7,000 miles across the Atlantic to Cape Verde, despite never having been there before: He had lived his entire life in captivity. But even smaller-scale rambles are no less awe-inspiring, such as the visualization of a carpenter ant colony over 40 days or the swirling ascent of vultures into thermal drafts.

As the authors point out, discerning the paths of animals once meant following their physical footprints and traces, and grasping the full range of animals’ travels was extraordinarily difficult for mere two-legged hominids. In the 19th century, some ornithologists began attaching threads and tags to the legs of migrating birds in the hopes of proving that they returned to the same places. Today, in the era of Big Data, biologists can generate and access heaps of information generated by satellite tags, radar, drones, feather-light geolocators, accelerometers, and GPS. (Cheaper batteries and DNA sequencing also help.) In some instances, scientists have deputized animals themselves as cartographers, attaching transmitters they know will be carried into unknown places, depths, or heights, as is the case with elephant seals in the Antarctic.

Some biologists have pioneered these technologies themselves, creating new engineering and designs to answer questions raised by their research, thereby advancing the field known as movement ecology. Although Aristotle wrote about the movements of animals more than 2,300 years ago, this scientific field is nascent. Its advocates argue that movement is not just a fundamental characteristic of life but one of its prime drivers. The mechanisms and patterns of organisms’ movements influence populations and ecosystems, evolution, and diversity. Conservationists have incorporated movement ecology into their own work, realizing that if humans are to protect animals, they must protect the routes they travel.

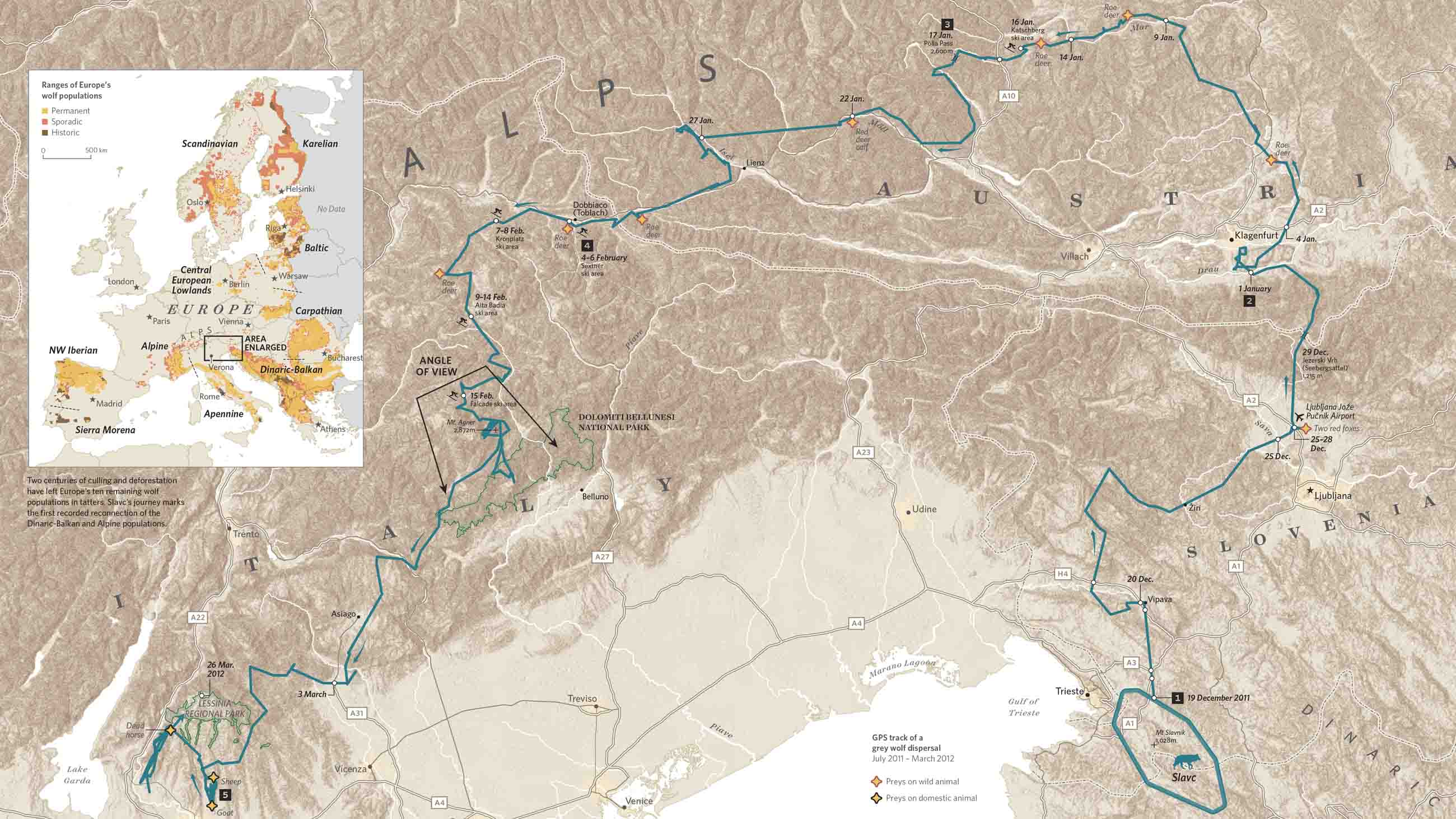

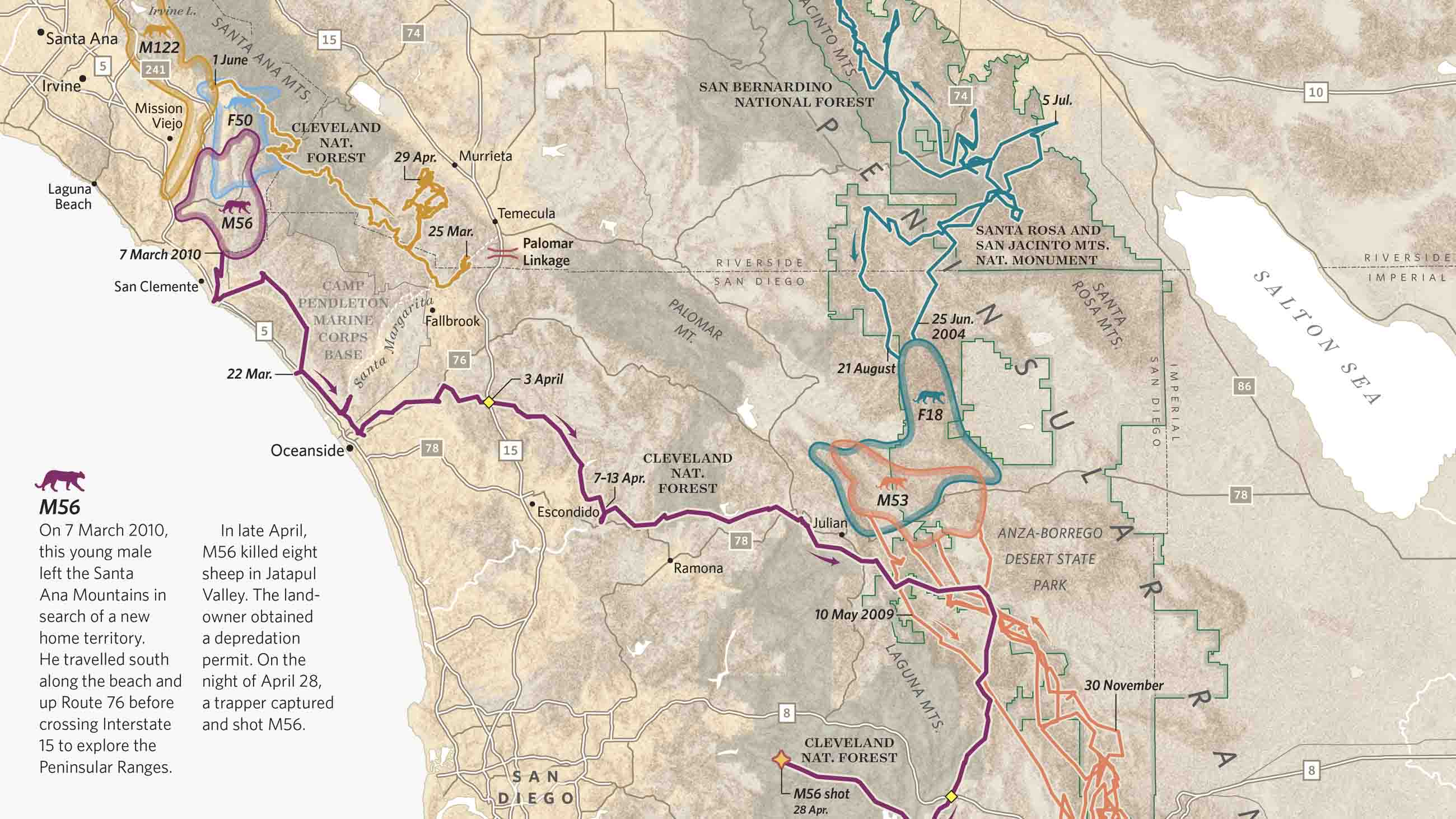

Spending any amount of time with “Where the Animals Go” will render readers susceptible to the same shift in consciousness experienced by Uberti: As he and Cheshire write, these maps allow us to “see ourselves and the animals — walking, swimming, flying — intertwined in one great beautiful tangle of tracks.” Indeed, tracking an animal through time and space transforms it from a mere object of scientific interest into a story whose unsolved mysteries capture our imagination. How did the African elephant Ramata come to inhabit 12,000 square miles, the largest home range of any elephant? Why did the mountain lion known as M56 finally decide to cross Southern California’s Interstate 15 — the only mountain lion known to do so — only to be shot and killed? What led the wolf Slavc to ascend thousands of feet up a mountain in the Alps to sleep the day away in a place known as the Eternal Plains?

The anthropologist Tim Ingold has written that even though we tend to think of humans and other organisms as blobs surrounded by an environment, life on earth is really a meshwork of entangled lines. The maps in “Where the Animals Go” teach us that individual animals are not objects but occurrences, not just nouns but verbs. This book invites us to engage in a radical act of rapport with animals as sentient, autonomous beings.

Indeed, the maps speak volumes about the overwhelming insecurity animals face in a world of human sprawl, habitat degradation, and climate change. The authors seem driven by a belief that the tracking revolution in biology proves that technology can support rather than threaten the natural world. But their book also shows how far we are from achieving what a pioneer of movement ecology, Torsten Hagerstrand, identified as its goal back in 1976: letting “fellow animals and plants live their lives in peace.”

M.R. O’Connor, a 2016-17 Knight Science Journalism fellow at MIT, writes about the politics and ethics of science, technology, and conservation. Her first book, “Resurrection Science: Conservation, De-Extinction and the Precarious Future of Wild Things,” was named one of Library Journal’s and Amazon’s Best Books of 2015. Her book on the science of human navigation will be published by St. Martin’s Press in 2018.