The Quest to Find and Identify Missing Persons

A band played as the Pewabic eased away from the docks at Houghton, Michigan on Aug. 8, 1865. Ladies in fine silk dresses and men in black top hats waved from the upper deck to a crowd onshore wishing them bon voyage for a 10-day journey to Cleveland. Later that evening, first-class passengers enjoyed dinner, dancing, and champagne in the steamboat’s dining room, then retired to their stately sleeping quarters with water views. Other passengers slept in steerage on blankets and hay set among 250 half barrels of fish, 27 rolls of tanned leather, and nearly 500,000 pounds of copper and iron ore.

The next day, one of the worst and most mysterious maritime disasters in Lake Huron’s history would unfold.

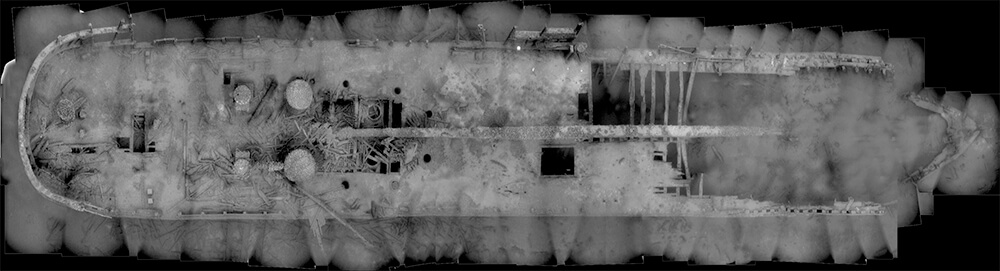

As the Pewabic passed its sister ship, the Meteor, possibly in an attempt to exchange newspapers or mail, the Pewabic suddenly veered and the Meteor struck the ship just below its wheelhouse, boring a gaping hole that quickly flooded. Within minutes, the Pewabic’s crew, passengers, cargo, and only existing manifest vanished into the deep, plunging 165 feet to the lake bottom, where the ship still rests today, preserved by freezing freshwater. “It’s the gravesite of at least 33 people who went down — some estimates vary widely and even pass the hundred mark,” said Philip Hartmeyer, a marine archaeologist for NOAA Ocean Exploration, whose research provides many of these details about the ship’s last voyage.

The Pewabic is among more than 200 vessels strewn across “shipwreck alley” in Lake Huron’s Thunder Bay. The region is currently serving as one of three worldwide maritime laboratories for a cutting-edge technique that could be a major advance for the field of forensic science. Their goal is to develop a unique protocol for finding missing people: the use of environmental DNA, an emerging tool that can detect genetic materials in a bottle of water or a scoop of seafloor sediment. The multimillion-dollar effort is being funded by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, or DPAA, an arm of the U.S. Department of Defense, with the hopes that the technology will help search for, locate, and repatriate U.S. Service members lost in past conflicts.

Unlike DNA, which is collected directly from an individual — whether from a cheek swab, a strand of hair, fingernail clipping, tooth, or bone — eDNA is the genetic material continually sloughing off humans and every other living creature. It’s a junkyard of degrading cells that is omnipresent in air, water, and soil. With advancing genetic analysis, scientists have found eDNA in footprints in the sand and on the surface of leaves in a forest. In short, eDNA is everywhere — and it’s being heralded as one of the greatest new scientific frontiers.

Until recently, eDNA research focused mainly on identifying animals and microbes in ecosystems and urban jungles, but by analyzing all of the genetic material in a cup of water or sand, scientists are now working to find traces of humans too, including those who perished decades ago.

From the stormy waters of Lake Huron to World War II battle sites off the coast of the island of Saipan in the Pacific and Palermo, Italy, researchers collaborating with DPAA are sampling areas where there are known human remains. Their goal is to prove the concept of using eDNA this way and simultaneously develop a protocol for adopting eDNA as a “scouting tool,” said Charles Konsitzke, associate director of University of Wisconsin’s Biotechnology Center, where the samples are being analyzed.

The research is still in the fledgling stages, but if the concept is proven, he said “this can be an absolute game changer” not only for finding lost soldiers but also, perhaps in the future, helping to solve other mysteries too.

The U.S. makes a promise to service members that “no soldier will be left behind,” but finding human remains in downed warplanes and ships in the world’s vast oceans is a formidable challenge. More than 81,000 Americans are still labeled as missing from conflicts spanning from WWII to the first Gulf War, with over 41,000 of them believed to be lost at sea.

Currently, whenever there is a site with high probability of human remains, an archaeological team is dispatched to do excruciatingly detailed, square meter grids-excavations of the entire area, sometimes spanning years, until they find what they’re looking for and repatriate the fallen soldiers — or not.

U.S. Marine casualties from the Battle of Saipan are buried at sea in July 1944. While these men were identified, more than 81,000 Americans are still labeled as missing from conflicts spanning from WWII to the first Gulf War.

Visual: FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Sunken war relics are sometimes covered in decades of sand and silt, barely visible, or completely buried. It’s a painstaking, slow process: The sediment is packed in bags that are hoisted up to a support boat, where they’re sieved for revealing artifacts, such as a bone, a tooth, a ring, or a dog tag. Underwater archaeologists work similarly to their counterparts on land, except they breathe compressed air and navigate sea currents and visibility that can suddenly drop to zero. At deep sites, divers are limited by how long they can safely stay under water; sometimes they have less than an hour to do their work.

The great hope is that eDNA will make the process of recovery much more efficient: “We’ll know that a team isn’t losing time by excavating an underwater site where there are no remains,” said Konsitzke. “They’d go right to a site that has seen bits of human DNA picked up by the eDNA scouting tool, which means more service members will be recovered.”

Kirstin Meyer-Kaiser, a marine biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, is one of the scientists leading field research for the eDNA project. She says she got involved with the project after a DPAA staffer mentioned how the agency was looking for emerging techniques to help localize human remains. “The term they were using at the time was ‘bone sniffer,’” she said. In other words, a method to detect invisible traces of humans in seafloor sediments and the water column without excavation. “The goal of this project is not to identify any particular individual,” she stressed. “It’s can we figure out if there is a human here?”

The researchers are investigating two key questions: Is it possible to tell the difference between a site that is likely to hold human remains and a site that doesn’t? And can eDNA be used to localize a search to an area with higher probability of remains?

“This can be an absolute game changer.”

The DPAA suggested three test beds for the research, including two WWII sites. One is along the coast of Palermo, Italy, where a U.S. B-17 bomber nicknamed “Devils from hell” and nine crew were shot down by enemy fighters. The second is along the Pacific island of Saipan, where the coastline is littered with downed aircraft, ships, and vehicles from when U.S. marines invaded in June 1944.

Jennifer McKinnon, an underwater archaeologist at East Carolina University, has been working in Saipan since 2007. “The battle for Saipan was very strategic for the U.S.,” she said, “because it placed the U.S. close to the Japanese homeland and allowed them to set up B-29 flights from the Mariana Islands to Japan and ultimately to drop the two bombs that ended the war.” Every time she goes to Saipan, she marvels at the abundance of wartime relics. “You can’t drive down a road without seeing a tank, whether it’s Japanese or U.S., sitting in the water or on land,” she said. “There’s markers of that battle everywhere you turn.”

In recent years, scientists have been using eDNA analysis as a tool for trying to better understand fish populations and biodiversity of bacteria and other life living on sunken aircrafts in Saipan. In March 2022, the eDNA research expanded to humans when McKinnon led a team of archaeologists, divers, students, and other specialists to collect samples near three submerged aircraft along the coast: a Hellcat fighter plane, a TBM Avenger three-seat bomber, and a Martin PBM Mariner twin-engine float plane, the first two of which are believed to possibly have human remains inside or nearby. The Mariner, where everyone onboard was rescued, was used as a control site for comparison.

Disentangling human eDNA from plants, animals, and microbes is easier than parsing the difference between historic human remains and the person who went for a swim yesterday — or the sewage runoff trickling from the town next door — say the scientists. The key to figuring out the latter is the length of the eDNA fragments. “We were looking for very, very short fragments, on the order of 30 to 40 base pairs,” said Meyer-Kaiser. “And then anything larger than 150 base pairs, we considered to be indicative of modern human presence, maybe recreational divers from the day before, or divers from our team.”

The third study site is in Thunder Bay, where the Pewabic met its mysterious end.

The bay is one of the most treacherous stretches of water in the Great Lakes, prone to violent storms, dense fog, and sudden gales, and therefore home to a large number of easily accessible shipwrecks. “They don’t call it Thunder Bay for nothing,” said Stephanie Gandulla, a maritime archaeologist with the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

The region is especially well-suited for many types of research, including eDNA, she said, because the cold, clear freshwater that has preserved the shipwrecks so well. In addition to the Pewabic, scientists are also surveying for eDNA at three other nearby shipwreck sites associated with a range of human losses — the Corsican, a wooden two-masted schooner that collided with another ship and sank in 1893 with six crew onboard; the Grecian, a steel freighter that was being towed to Detroit for repair when it got stuck on a reef and sank without casualties in 1906; and the Norman, a freighter that wrecked in 1895 when it collided with another ship in dense fog, and plunged 200 feet, killing three crew.

“The goal of this project is not to identify any particular individual. It’s can we figure out if there is a human here?”

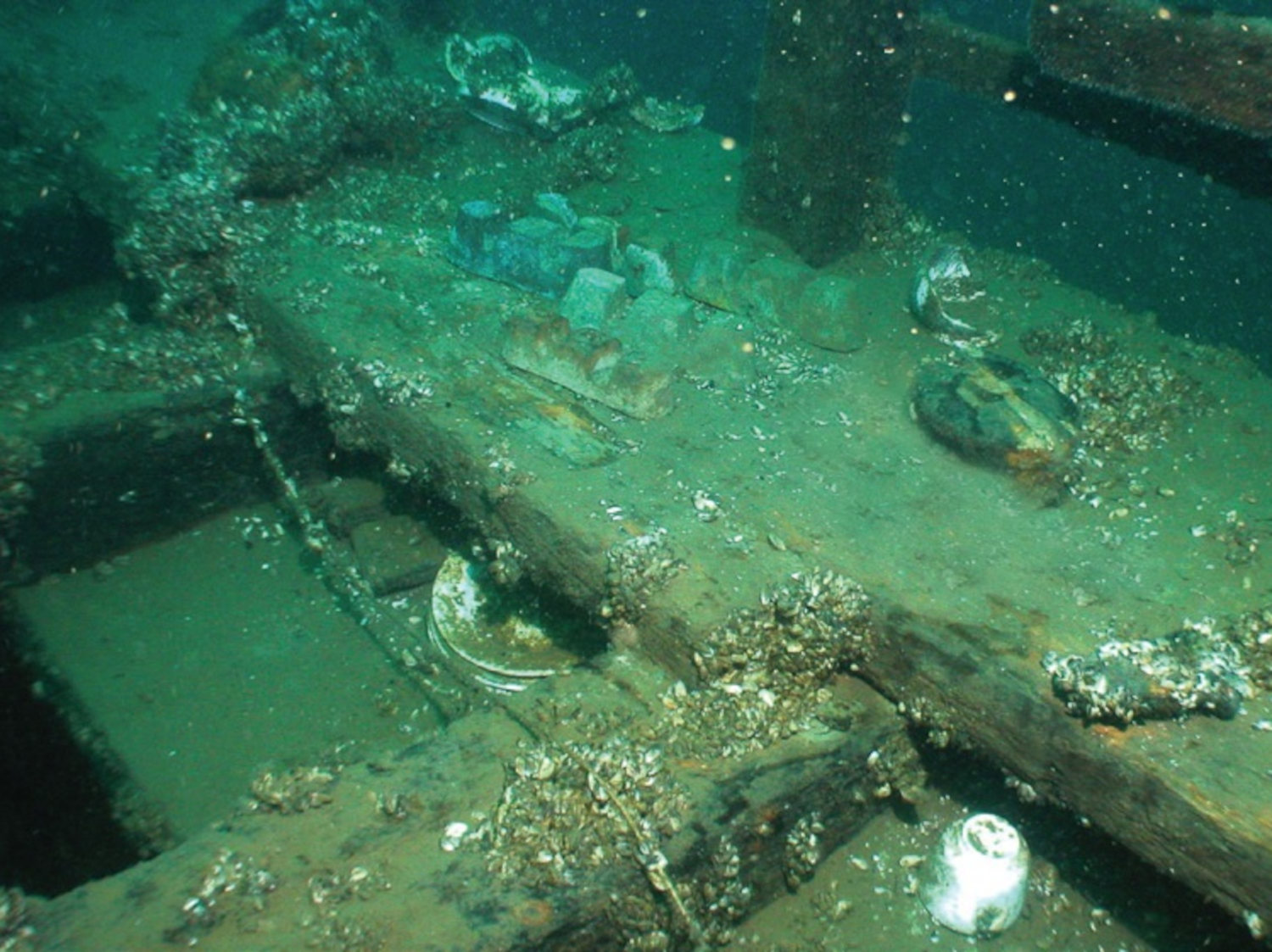

In the summer of 2022, a team of divers collected samples at all four shipwrecks. They identified an epicenter for each site that they thought would have the highest likelihood of human remains, usually next to the hull of a ship. From there, they collected bottles of water and jabbed foot-long clear PVC tubes into the lake floor to extract sediment at increasing distances: one meter, two meters, four meters, and eight meters. The core and water samples were placed in milkcrates and towed to the surface on a rope, then frozen and shipped to the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center for sequencing and bioinformatics to reveal which fragments of DNA are human, how long those fragments are, and what other organisms are present.

Konsitzke says the analysis is currently underway, but it’s too soon to announce any conclusions. If the results do show that eDNA is a viable tool for locating remains, the next subject he’d like to tackle is whether it’s possible to identify the remains’ ancestry.

The million-dollar question: Will eDNA collected near wrecks one day become a viable tool for identifying a particular person, allowing lost soldiers to be repatriated to their families for burial? If it’s possible, it’s “light years away,” said Konsitzke.

Some other recent studies have shown success determining ancestry and identities from eDNA in certain settings and conditions. In a Florida research study analyzing water cupped from a creek in St. Augustine in 2022, researchers got a snapshot of the genetic ancestry of the people living nearby, roughly matching racial data reported in the latest census (though the scientists recognized that racial identity isn’t a perfect indicator of ancestry). Scientists from Oslo University Hospital’s forensic research center published a study in 2022 about piloting a technique to retrieve human DNA from air samples and succeeded in matching a full DNA profile of at least one person who had occupied an office space.

Each new study raises discussion — and concern — about the potential for eDNA to be used for good and ill, including as a forensic tool in crime investigations. Say, for instance, a body was buried, then dug up and moved: The eDNA, Konsitzke says, could show that the murder victim had been present at the first location.

Law enforcement agencies, though, might want to avoid immediately adopting such a pioneering scientific technique. The National Registry of Exonerations reports that more than 700 wrongful convictions have been based on flawed forensic science, such as bite mark analysis and microscopic hair matching, illustrating why eDNA — or any other new scientific technique — would need to be heavily vetted before being presented as evidence in a courtroom, say legal experts.

“The stage of the investigation right now is very, very baseline: Does this work?”

As the DPAA-funded studies progress, agency spokesperson Ashley Wright says the plan is to move cautiously. “Even with promising results, further study and development followed by extensive validation would be necessary before analysis of eDNA would be applied to DPAA site investigations,” she wrote via email.

Meyer-Kaiser expresses gratitude for the passengers of the Pewabic and other sunken ships and planes involved in the study. They’ve been “instrumental in helping us ground truth methods that may help recover and repatriate fallen soldiers,” she said. “There’s a very strong sense of purpose as we go about this.”

Might eDNA one day revolutionize the way crimes are investigated, solve cold cases, or uncover the location of clandestine burial sites? “Our brains are running on what else could this be used for,” said Meyer-Kaiser. “But the stage of the investigation right now is very, very baseline: Does this work?”

UPDATE: An earlier version of this article included a photograph depicting human remains at the bottom of Lake Huron, attributed to the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. In deference to Michigan state law regarding the depiction of human remains, the photograph has been removed and replaced with an image of copper ingots and other artifacts on the deck of a shipwreck.

SHREDS OF EVIDENCE: THE COMPLETE SERIES

Part 1: DNA Deluge

Part 2: Hidden Bugs

Part 3: Evasive Traces

Part 4: Market Buzz

Part 5: Genetic Net

Part 6: Lost Souls