Slow Burn: The Emerging Science of Fire Deaths

On a hot September day in Texas Hill Country, the fire picked up, its flames popping the Jeep’s burning tires and airbags like plastic chip bags. Thirty or 40 feet away, a crew of firefighters, law enforcement, and forensic anthropologists watched the burning wreckage from the safety of a white canopy, while a firefighter in full protective gear waited, his hose at the ready.

Inside, a figure sat motionless in the passenger seat.

Until the fire began, the crew’s choreography — setting up temperature-gauging thermocouples, readying cameras, unspooling the firehose — evoked a buzzing film set. Now all was still but the melting car. After several minutes, a thermocouple on the Jeep’s ceiling read 1,100 degrees, triggering a timer. At that temperature, termed a flashover, heat becomes so intense that anything capable of catching on fire does.

The car windows snapped from the doors and shattered. At 20 minutes, the scene’s director, Steve Seddig, a Texas State University graduate student and retired fire investigator, raised his hand to the firefighter with the hose, who sent a jet of water into the flames. But it was far too late for the passenger, who had already been dead for months — and whose final earthly act was to advance the science of how extreme heat ravages bodies.

While the vehicular carcass continued to smoke, the team moved to a second burn: another car with another donated body in the passenger seat. There were five stagings in all: two cars, along with three reproductions of furnished bedrooms. Pacing through the sets in a fire jacket and helmet was Seddig, a tall bespectacled Texan with an angular jawline. Months of planning — “all for a four-minute burn,” he barked as he zipped across his set.

“It can’t be just an art form — it has to be a science.”

Each sequence played out on a sandy clearing at Freeman Ranch, a vast landscape of brush and trees operated by Texas State University and home to the Forensic Anthropology Center’s body farm, where researchers study a subsection of taphonomy, the science of animal and plant death and decay. Each year, a class joins the center’s forensic anthropologists and fire investigators to sharpen their sleuthing skills, using donated cadavers to help further their research. The taphonomists can learn about the effect of fire on decay — making incremental additions to a growing inventory of data — and the fire investigators can better grasp how human remains should guide their work.

The course, which is in its 12th year and takes place about halfway between Austin and San Antonio, unites two rapidly evolving scientific fields: fire dynamics and forensic anthropology. Their real-world connection happens when human remains are found at a fire scene. That’s rare — a rural fire investigator may go an entire career without encountering a fatality. But when it does happen, it demands especially deft handling. To help ensure that a tragedy has a successful investigation, the week-long course introduces practitioners to the latest research and provides the rare opportunity to observe fatal fire scenes.

Fire investigation “used to be called an art form,” said Joseph Ellington, a lecturer at the September course, as well as a fire and explosions consultant who’s spent decades as a fire investigator in Texas. “It can’t be just an art form — it has to be a science.” The San Marcos course — along with two others offering a similar model, one in San Luis Obispo, California, and the other Cullowhee, North Carolina, in association with Western Carolina University — presents itself as an antidote to that history, which has often undercut a solid investigation.

While standard practices are becoming more common in the field, some key fundamental knowledge, such as how to handle a human body as evidence, still eludes basic training.

“That’s not something that we cover in fire academy,” said Amy Thomas, a fire inspector and investigator in Leander, Texas who attended the San Marcos course. “NFPA 921,” a guidebook considered to be a holy scripture of fire investigation, only has three pages on how to handle fatalities.

Thoroughly trained investigators may be at a disadvantage, too. As fire dynamics and forensic anthropology have developed into full-fledged fields, and technology has evolved, settled practices have become uprooted. “Fifteen years ago, nobody knew any of this stuff,” said Ed Nordskog, a former detective with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and longtime fire investigator and profiler. “The very people we expect to get the truth out of at autopsy, which is supposed to be a scientific thing, knew absolutely nothing about what happens to a body in a fire.”

Fire investigation and forensic anthropology are relatively young fields of study — so young, in fact, that many pioneering researchers are still alive. Until the 1970s, both fields were largely dominated by independent researchers and gumshoe fire investigators, and they were often intertwined with bunk science.

American fire safety research emerged in 1973 when the National Commission on Fire Prevention and Control released a seminal study called America Burning. “The U.S. felt that it had a lot of fire deaths, more than other countries per capita,” said James Quintiere, professor emeritus at the University of Maryland’s Department of Fire Protection Engineering. “And they invested in improving fire safety.”

The report led to a host of positive effects, from new fire regulations to the establishment of the U.S. Fire Administration, a federal agency which supports fire prevention services through research and training. Still, the growth of fire science wouldn’t last. In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan gutted federal fire safety programs, which, according to Quintiere, may partially explain the divide between knowledge centers of fire safety and practitioners of fire investigation. Beyond drawing two distinct crowds — one that’s research-minded and another directly interested in public safety — federal policy cleaved them further apart.

Yet one small connection between those crowds soon emerged. “What happened in the late 1980s is, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms got the responsibility of investigating fires as well as explosions,” Quintiere told Undark. “They started to recognize that they were learning, really, mythology instead of science.”

Fire investigation and forensic anthropology are relatively young fields of study — so young, in fact, that many pioneering researchers are still alive.

That revelation didn’t remake the world of fire investigation, he added, but a well-funded law enforcement agency with an interest in cutting-edge practices did offer a new go-between. Now, standard procedures tend to stem from a small cluster of organizations, such as the International Association of Arson Investigators, or IAAI. One such group, the National Fire Protection Association, or NFPA, publishes literature that investigators across the country rely on for operational guidelines.

Despite best efforts by those organizations to fill the breach, exacting practices still suffer from lag time on the path to widespread usage. For years, for instance, the “NFPA 921” guidebook empowered investigators to decide their hypothesis on a case was correct even in the absence of any proof. “It may be possible to make a credible determination regarding the cause of the fire, even when there is no physical evidence of the ignition source identified,” reads the 2008 edition. The legal implications are disturbing, said Thomas Sing, a fire investigation professor at Eastern Kentucky University and NFPA technical committee member: “You don’t want to put someone in jail on a lack of evidence.”

The text was removed from the guide in 2011, a signal that firmer practices were making their way into investigations. “The field emerged,” said Quintiere. “And became a proper science.”

As for the study of decomposition, the field traces its professionalization to 1972, when the American Academy of Forensic Sciences minted a physical anthropology section. The field really got started, however, with a freak occurrence. In 1977, a disturbed Civil War grave on a family plot in Franklin, Tennessee, drew the attention of authorities. Rather than the skeleton of Confederate officer William Shy, the sheriff found what looked like a fresh body in a tuxedo buried in the dirt. It appeared to be in the early stages of decomposition, with soft tissue intact. Suspecting some sort of convoluted crime, the sheriff teed up a homicide investigation by contacting subject matter experts.

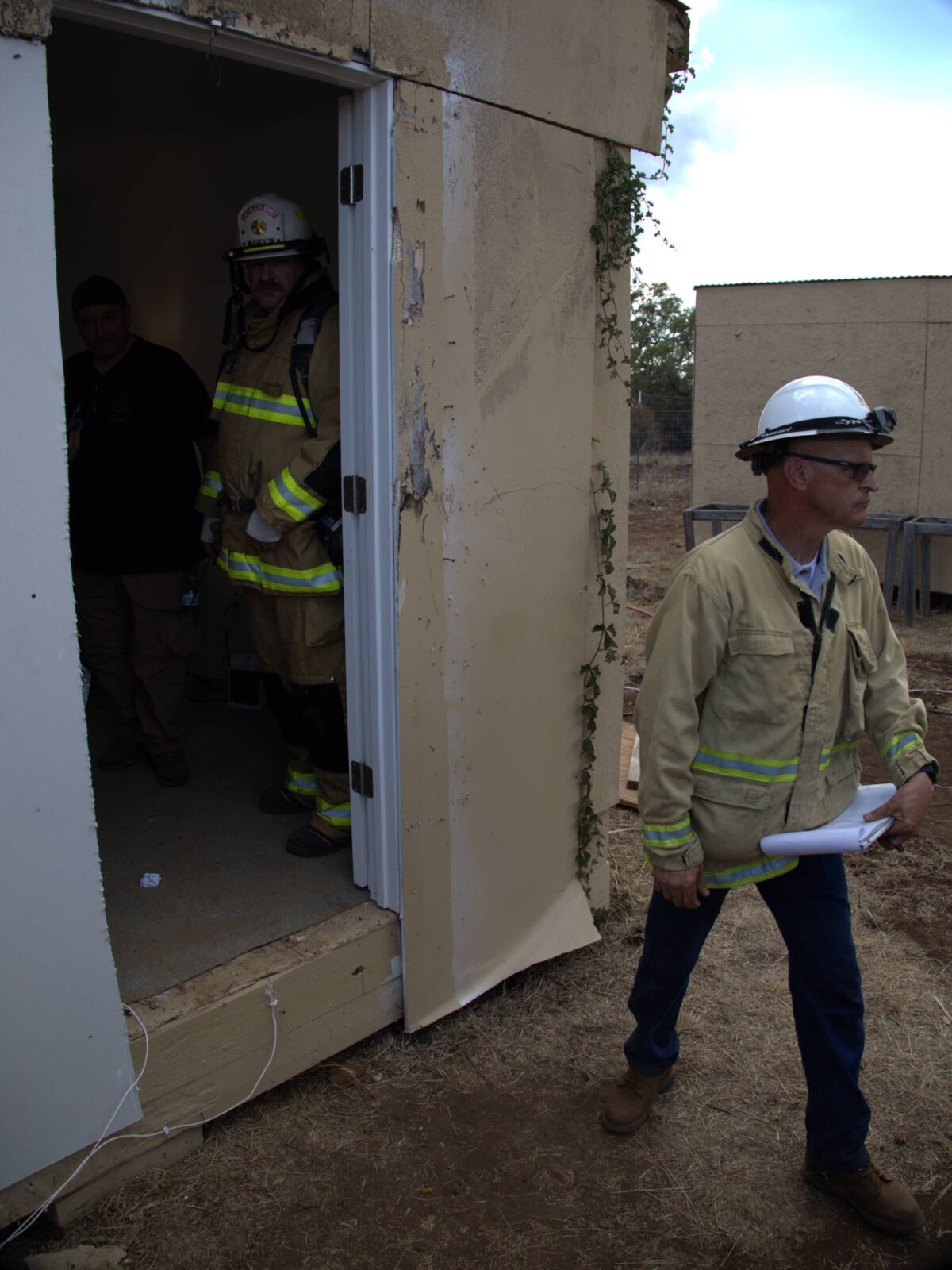

Steve Seddig, a Texas State University graduate student and retired fire investigator, at the San Marcos course in September. Sedding launched the course in 2013, after the Texas Forensic Science Commission released a report that noted a lack of science education in fire investigator training.

Visual: Forensic Anthropology Center at Texas State/Collin County Fire Investigators Association, Inc.

One was anthropologist William Bass, who arrived to help excavate the site. Initially, Bass guessed that the specimen had been decaying for less than a year. But over the following weeks, details like the presence of embalming fluid, no labels on the tuxedo, and unfilled cavities pointed to the truth: Shy’s body had been in its proper resting place the entire time. Bass’s first guess was 112 years off.

“As Colonel Shy had made painfully clear,” Bass later wrote, “Our understanding of postmortem processes was quite limited.” The case drove him to establish the Anthropology Research Facility in 1981 at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville to more closely study what happens to the human body after death — the first body farm. The facility received its first contribution that spring, when a local resident donated the remains of her recently deceased 73-year-old father.

The broader field didn’t truly formalize until the mid-2000s, when several other universities opened their own body farms, where researchers monitor corpses mummifying in the sun, buried in the dirt, protected from scavengers by metal cages, left exposed to the whims of nature, and more. Western Carolina University in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains opened its facility in 2007. Then in 2008, the Forensic Anthropology Research Facility at Texas State University in San Marcos opened.

For the last 15 years, researchers have studied the remains of body donations across the facility’s 26 acres — part of the larger 3,500-acre Freeman Ranch — where the present-day fire course takes place. The initial three-cadaver inventory at the San Marcos facility has since expanded to 842 human remains, with about 1,500 living people who plan to donate their remains in perpetuity.

In addition to the annual fire investigation course, Freeman Ranch hosts a course for homicide detectives. Body farm work also has an appeal for medical examiners, where partially decomposed specimens are always on the docket. “But there always are larger applications,” said Petra Banks, a Ph.D. student in the anthropology department at Texas State University. There are limitations in how well scientists understand bone fractures, she said, and studying them on the body farm could produce knowledge that informs treatment. “It all crosses,” she said. “The disciplines all start to blend together.”

Fire doesn’t erase evidence from a scene, but it does transform what’s there, making it difficult to interpret how the burn happened based on the objects that it altered. The aftermath of different events may look nearly identical, with truth only observable under microscopic levels of examination. As flames wick the water from a body, muscles tighten and flex into what’s known as the “pugilistic posture,” said Daniel Wescott, director of the Forensic Anthropology Center at Texas State. “The hands are curled up, and then you get the arms, the hips will flex up. The knee will flex. All that kind of stuff.” A body may roll out of bed or seemingly lean forward in a chair, leading investigators astray. Contracting muscles can fracture bones, too, or cause an arm to fully bend at the elbow, insulating skin from the flames. Misreading any of those signs can obscure the truth. Were someone’s legs broken before the fire — or because of it?

According to Nordskog, skin doesn’t simply burn under the intense heat of a flame; it chars, then splits open. “And it’s horrifying,” he said. Out from those splits comes fat, which acts as low-grade gasoline. Long after other fuel sources are exhausted, he said, “your body can continue burning.” With enough fuel muscles burn next, followed by the tendons, and then bone. “Given enough time, it’ll burn you mostly away” — but, and this is crucial — “never completely,” he added.

Fire doesn’t erase evidence from a scene, but it does transform what’s there. The aftermath of different events may look nearly identical, with truth only observable under microscopic levels of examination.

That endpoint is where the investigator begins. The position of the body paired with the way it has been incinerated can offer clues to the flame’s origin and cause. Precise details, such as the coloration on burnt bone, can reveal the duration, temperature, and oxygen levels — the fuel source — of a fire.

Yet an investigator’s misinterpretation of those details can spark a tragedy. In 2004, Texas executed a man named Cameron Todd Willingham for setting a fire in 1991 that killed his three daughters. After he died, the methods fire investigators used to prove it was arson, and not an accident, came under intense scrutiny. In the years since, he has been all but exonerated. The year Willingham died, another arson convict on death row was exonerated on similar grounds. In 2011, the Texas Forensic Science Commission released an 893-page report on fire investigation practices in the state. “It identified investigative evidence that had been debunked as far as the validity of it over the years,” Seddig told Undark.

The report also found a “lack of science education on the part of many fire investigators.” There wasn’t an adequate framework for teaching the fundamentals to investigators, the report noted, who more commonly “relied heavily upon the teachings of their mentors regarding the nuances involved in interpreting incendiary indicators.”

Under those conditions, Seddig, then the fire marshal of Wylie, Texas, launched the fire death course in 2013, basing it on a Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives fire course he took a decade earlier and honing it after taking another forensic fire death investigation course in 2014. It began by burning two hogs, donated by a regional pork company. Buttressing the course’s first trial-and-error iterations were the resources Seddig could scavenge: the second year’s hogs were hunted. Another year, the course organizers partnered with an indie film crew that needed a burning house scene.

In 2015, Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas, agreed to host the course and contribute human specimens from its own body farm. There, it took on a more stable form and began to draw attention from outside of Texas. Investigators from other states and agencies began to attend. Classes might consist of dozens of attendees. Four years later, the course came to Freeman Ranch.

“It’s great to have this experience behind us,” said Jeremy Trahan, battalion chief of Travis County Fire Rescue in Austin, Texas, who has attended the course as a student and now volunteers to help set up the course. Arriving at a fatal scene in the field, alumni should be armed with confidence, he added: “Okay, we’ve worked this, we’ve done this in training. We know where we’re going — and what for.”

The aim of the course is not simply to preach the gospel of procedural investigation, but also to ensure that those procedures are up to date. After all, the science of fire and decomposition have continued to evolve. And an advance in one field may affect another.

Using donated cadavers from places including Tennessee’s body farm, independent forensic anthropologist Elayne Pope has been able to disprove numerous assumptions about how the body deteriorates in a blaze.

Some of her findings have prompted revisions to “NFPA 921.” Until 2004, a pervasive myth was that under enough heat an intact human skull would explode. So, she burned 40 heads. “And basically, none of them exploded,” Pope told Undark. “Through testing we were able to say, no, that’s total BS, bad science.” More revelations: Neither blisters nor a protruding tongue can confirm that someone found in the aftermath of a fire was alive when it burned. Bizarre as those discrepancies are, they become relevant in paramount moments, both in criminal courts and on a medical examiner’s table.

During burns, the thermocouples that record structure temperatures are also used to measure the cadavers: on the roof of the mouth, in the cheeks, on the hands, the femur, the sixth rib, and the pelvis.

It’s not easy to find a human head that’s available for such research, however. Let alone 40. The immense value of each donation means that burning more than several at once would be gratuitous. At the same time, there needs to be enough data upon which to build a hypothesis. The field, then, relies heavily on datasets that grow over time. “You do these small studies, but it’s the accumulation of that,” Wescott said. “There’s just no way of laying out 100 individuals.”

The data helps fuel a dynamic understanding of flame and decomposition. “I learn new stuff every year,” said Pope. Not just about the nature of fire deaths, but fire more broadly. “With fire investigators, 20 years ago they were taught these myths and wives’ tales,” she added.

Because fire deaths are so rare, the core of the San Marcos course, and others like it, may be to prepare practitioners for those scarce moments, but by extension it’s promoting the need for more modern practices — and for attendees to see their work as scientific. Accordingly, the utility of technology in the field also features heavily on the course syllabus.

One more recent tool of the trade is LiDAR — a type of scanner, originally developed as a surveyor’s tool, that uses light to measure distance. LiDAR data can generate high-resolution, three-dimensional maps of a space and are accurate to within a fraction of an inch. For a fire investigator examining a scene before handing it over to police, insurers, or rightful owners, capturing a thorough impression ahead of irreversible contamination is invaluable. “You can basically walk your jury, walk your DAs through a scene, exactly how you saw it,” said Thomas Elizondo, a fire investigator with the Hays County Fire Marshal’s Office in Texas. “Let’s say, hypothetically, it was a homicide case, and it went to a cold case. Years later on, whoever is looking at that case can go back through your scenes.”

“You do these small studies, but it’s the accumulation of that. There’s just no way of laying out 100 individuals.”

Another promising technological development is fire modeling. Here, computer programs with visual interfaces, which resemble The Sims or architectural software, simulate fires. Users can replicate real-world structures adorned with objects such as mattresses and lamps. The program can consider the specific material of innumerable consumer products and render what happens to them during a fire. An investigator could create an exact replica of a home — complete with furniture, appliances, and tchotchkes — and see what happens when a flame starts next to, say, the credenza.

Contrast that with what it’s replacing: “When I first started in this profession in 1983, if I had three fire deaths and I believe that the fire started in the refrigerator in this room, the attorney might ask me to go out and build this house exactly the same way,” said Ellington, who gave a presentation on computer modeling to the class. “Put that refrigerator in the house and put all the contents in it and burn it. Why do that? Because that’s dangerous, to say nothing to the effect that it’s cost-effective just to build a mathematical model on the computer.”

All of that processing power stalls under the wrong user. “Some investigators just are like, ‘I don’t care about this new stuff — I just do my time,’” said Sing, the fire investigation professor at Eastern Kentucky University. “They’re just going to retire and that’ll be that. But then there’s a lot of fire investigators who are eager to learn.”

Back on the hot, autumn day at Freeman Ranch, after the fire course ends, the fire investigators step out to the parking lot, which was packed with emergency response vehicles from various Texas towns and counties. Some drove two hours to get home, but that didn’t seem to be a deterrent. “This is bucket list stuff for me,” said Thomas after the course wrapped up one day. “To have the incredibly rare opportunity to actually discuss in detail how this works from an investigation perspective — the science of how we burn.”

Will Peischel is a Brooklyn-based writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, the Guardian, and other outlets.

This is so well written. Ty