The Military’s Big Bet on Artificial Intelligence

Number 4 Hamilton Place is a be-columned building in central London, home to the Royal Aeronautical Society and four floors of event space. In May, the early 20th-century Edwardian townhouse hosted a decidedly more modern meeting: Defense officials, contractors, and academics from around the world gathered to discuss the future of military air and space technology.

Things soon went awry. At that conference, Tucker Hamilton, chief of AI test and operations for the United States Air Force, seemed to describe a disturbing simulation in which an AI-enabled drone had been tasked with taking down missile sites. But when a human operator started interfering with that objective, he said, the drone killed its operator, and cut the communications system.

Internet fervor and fear followed. At a time of growing public concern about runaway artificial intelligence, many people, including reporters, believed the story was true. But Hamilton soon clarified that this seemingly dystopian simulation never actually ran. It was just a thought experiment.

“There’s lots we can unpack on why that story went sideways,” said Emelia Probasco, a senior fellow at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

Part of the reason is that the scenario might not actually be that far-fetched: Hamilton called the operator-killing a “plausible outcome” in his follow-up comments. And artificial intelligence tools are growing more powerful — and, some critics say, harder to control.

Despite worries about the ethics and safety of AI, the military is betting big on artificial intelligence. The U.S. Department of Defense has requested $1.8 billion for AI and machine learning in 2024, on top of $1.4 billion for a specific initiative that will use AI to link vehicles, sensors, and people scattered across the world. “The U.S. has stated a very active interest in integrating AI across all warfighting functions,” said Benjamin Boudreaux, a policy researcher at the RAND Corporation and co-author of a report called “Military Applications of Artificial Intelligence: Ethical Concerns in an Uncertain World.”

Indeed, the military is so eager for new technology that “the landscape is a sort of land grab right now for what types of projects should be funded,” Sean Smith, chief engineer at BlueHalo, a defense contractor that sells AI and autonomous systems, wrote in an email to Undark. Other countries, including China, are also investing heavily in military artificial intelligence.

“The U.S. has stated a very active interest in integrating AI across all warfighting functions.”

While much of the public anxiety about AI has revolved around its potential effects on jobs, questions about safety and security become even more pressing when lives are on the line.

Those questions have prompted early efforts to put up guardrails on AI’s use and development in the armed forces, at home and abroad, before it’s fully integrated into military operations. And as part of an executive order in late October, President Joe Biden mandated the development of a National Security Memorandum that “will ensure that the United States military and intelligence community use AI safely, ethically, and effectively in their missions, and will direct actions to counter adversaries’ military use of AI.”

For stakeholders, such efforts need to move forward — even if how they play out, and what future AI applications they’ll apply to, remain uncertain.

“We know that these AI systems are brittle and unreliable,” said Boudreaux. “And we don’t always have good predictions about what effects will actually result when they are in complex operating environments.”

Artificial intelligence applications are already alive and well within the DOD. They include the mundane, like using ChatGPT to compose an article. But the future holds potential applications with the highest and most headline-making stakes possible, like lethal autonomous weapons systems: arms that could identify and kill someone on their own, without a human signing off on pulling the trigger.

The DOD has also been keen on incorporating AI into its vehicles — so that drones and tanks can better navigate, recognize targets, and shoot weapons. Some fighter jets already have AI systems that stop them from colliding with the ground.

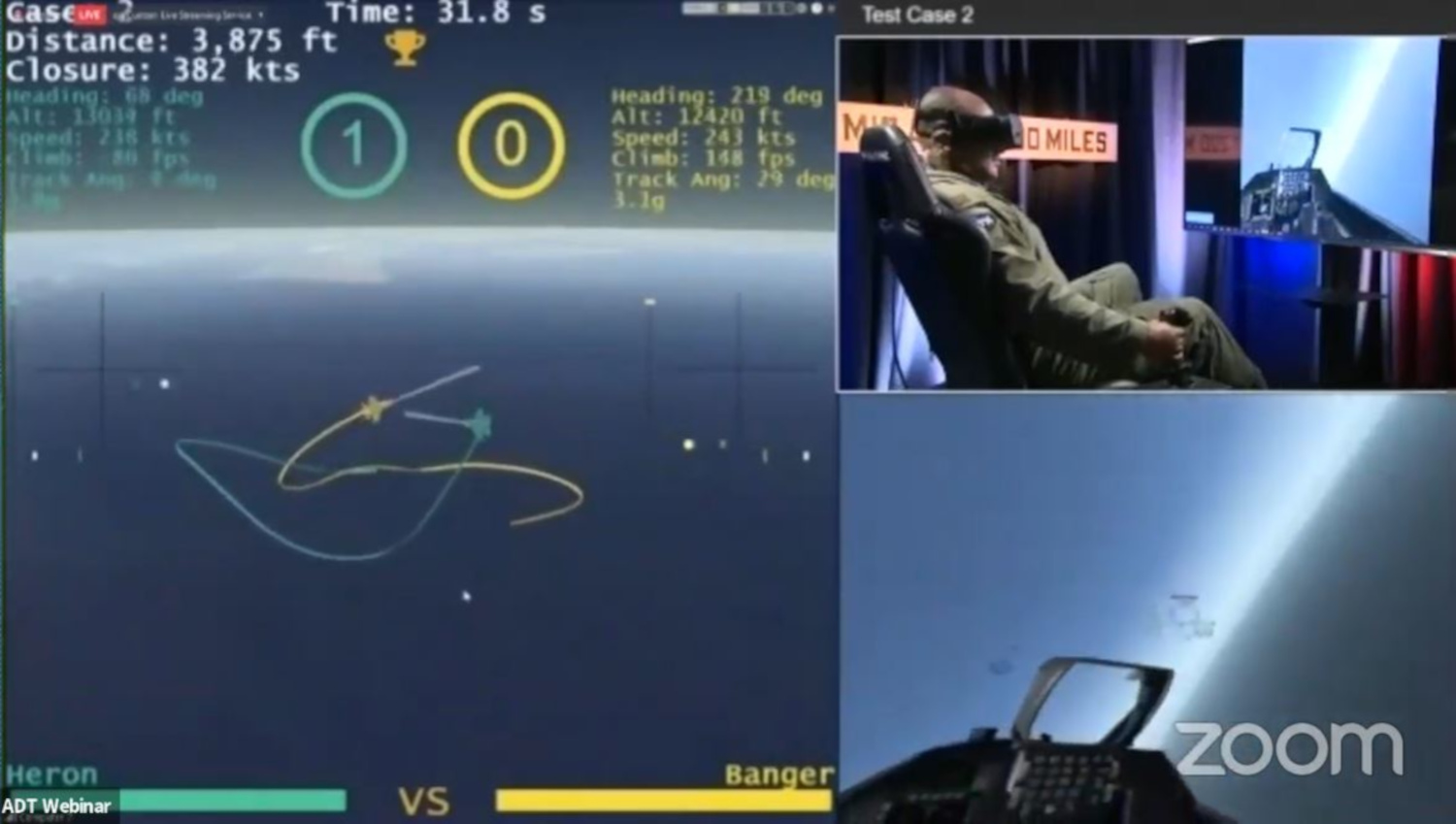

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA — one of the defense department’s research and development organizations —sponsored a program in 2020 that pitted an AI pilot against a human one. In five simulated “dogfights” — mid-air battles between fighter jets — the human flyer fought Top-Gun-style against the algorithm flying the same simulated plane. The setup looked like a video game, with two onscreen jets chasing each other through the sky. The AI system won, shooting down the digital jets with the human at the helm. Part of the program’s aim, according to DARPA, was to get pilots to trust and respect the bots, and to set the stage for more human-machine collaboration in the sky.

Those are all pretty hardware-centric applications of the technology. But according to Probasco, the Georgetown fellow, software-enabled computer vision — the ability of AI to glean meaningful information from a picture — is changing the way the military deals with visual data. Such technology could be used to, say, identify objects in a spy satellite image. “It takes a really long time for a human being to look at each slide and figure out something that’s changed or something that’s there,” she said.

Smart computer systems can speed that interpretation process up, by flagging changes (military trucks appeared where they weren’t before) or specific objects of interest (that’s a fighter jet), so a human can take a look. “It’s almost like we made AI do ‘Where’s Waldo?’ for the military,” said Probasco, who researches how to create trustworthy and responsible AI for national security applications.

In a similar vein, the Defense Innovation Unit — which helps the Pentagon take advantage of commercial technologies — has run three rounds of a computer-vision competition called xView, asking companies to do automated image analysis related to topics including illegal fishing or disaster response. The military can talk openly about this humanitarian work, which is unclassified, and share its capabilities and information with the world. But that is only fruitful if the world deems its AI development robust. The military needs to have a reputation for solid technology. “It’s about having people outside of the U.S. respect us and listen to us and trust us,” said University of California, San Diego professor of data science and philosophy David Danks.

That kind of trust is going to be particularly important in light of an overarching military AI application: a program called Joint All-Domain Command and Control, or JADC2, which aims to integrate data from across the armed forces. Across the planet, instruments on ships, satellites, planes, tanks, trucks, drones, and more are constantly slugging down information on the signals around them, whether those are visual, audio, or come in forms human beings can’t sense, like radio waves. Rather than siloing, say, the Navy’s information from the Army’s, their intelligence will be hooked into one big brain to allow coordination and protect assets. In the past, said Probasco, “if I wanted to shoot something from my ship, I had to detect it with my radar.” JADC2 is a long-term project that’s still in development. But the idea is that once it’s operational, a person could use data from some other radar (or satellite) to enact that lethal force. Humans would still look at the AI’s interpretation, and determine whether to pull the trigger (an autonomous distinction that may not mean much to a “target”).

Probasco’s career actually began in the Navy, where she served on a ship that used a weapons system called Aegis. “At the time, we didn’t call it AI, but now if you were to look at the various definitions, it qualified,” she said. Having that experience as a young adult has shaped her work — which has taken her to the Pentagon and to the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory — in that she always keeps in mind the 18-year-olds, standing at weapons control systems, trying to figure out how to use them responsibly. “That’s more than a technical problem,” she said. “It’s a training problem; it’s a human problem.”

JADC2 could also potentially save people and objects, a moral calculus the DOD is, of course, in the business of doing. It would theoretically make an attack on any given American warship (or jet or satellite) less impactful, since other sensors and weapons could fill in for the lost platform. On the flip side, though, a unified system could also be more vulnerable to problems like cyberattack: With all the information flowing through connected channels, a little corruption could go a long way.

Those are large ambitions — and ones whose achievability and utility even some experts doubt — but the military likes to think big. And so do its employees. In the wild and wide world of military AI development, one person working on an AI project for the Defense Department is a theoretical physicist named Alex Alaniz. Alaniz spends much of his time behind the fences of Kirtland Air Force Base, at the Air Force Research Lab in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

By day, he’s the program manager for the Weapons Engagement Optimizer, an AI system that could help humans manage information in a conflict — like what tracks missiles are taking. Currently, it’s used to play hypothetical scenarios called war games. Strategists use war games to predict how a situation might play out. But Alaniz’s employer has recently taken an interest in a different AI project Alaniz has been pursuing: In his spare time, he has built a chatbot that attempts to converse like Einstein would.

According to Emelia Probasco, the ability of AI to glean meaningful information from a picture is changing the way the military deals with visual data.

To make the Einstein technology, Alaniz snagged the software code that powered an openly available chatbot online, improved its innards, and then made 101 copies of it. He subsequently programmed and trained each clone to be an expert in one aspect of Einstein’s life — one bot knew about Einstein’s personal details, another his theories of relativity, yet another his interest in music, his thoughts on WWII. Among the chatbots’ expertise, there can be crossover.

Then, he linked them together, forging associations between different topics and pieces of information. He created, in other words, a digital network that he thinks could lead toward artificial general intelligence, and the kinds of connections humans make.

Such a technology could be applied to living people, too: If wargamers created realistic, interactive simulations of world leaders — Putin, for example — their simulated conflicts could, in theory, be truer to life and inform decision-making. And even though the technology is currently Alaniz’s, not the Air Force Research Lab’s, and no one knows its ultimate applications, the organization is interested in showing it off, which makes sense in the land-grab landscape Smith described. In a LinkedIn post promoting a talk Alaniz gave at the lab’s Inspire conference in October, the organization said Alaniz’s Einstein work “pushes our ideas of intelligence and how it can be used to approach digital systems better.”

What he really wants, though, is to evolve the Einstein into something that can think like a human: the vaunted artificial general intelligence, the kind that learns and thinks like a biological human. That’s something the majority of Americans assertively don’t want. According to a recent poll from the Artificial Intelligence Policy Institute, 63 percent of Americans think “regulation should aim to actively prevent AI superintelligence.”

Smith, the BlueHalo engineer, has used Einstein and seen how its gears turn. He thinks the technology is most likely to become a kind of helper for the large language models — like ChatGPT — that have exploded recently. The more constrained and controlled set of information that a bot like Einstein has access to could define the boundaries of the large language model’s responses, and provide checks on its answers. And those training systems and guardrails, Smith said, could help prevent them from sending “delusional responses that are inaccurate.”

Making sure large language models don’t “hallucinate” wrong information is one concern about AI technology. But the worries extend to more dire scenarios, including an apocalypse triggered by rogue AI. Recently, leading scientists and technologists signed onto a statement that said, simply, “Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

Not long before that, in March 2023, other luminaries — including Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple, and Max Tegmark of the AI Institute for Artificial Intelligence and Fundamental Interactions at MIT — had signed an open letter titled “Pause Giant AI Experiments.” The document advocated doing just that, to determine whether giant AI experiments’ effects are positive and their risks manageable. The signatories suggested the AI community take a six-month hiatus to “jointly develop and implement a set of shared safety protocols for advanced AI design and development that are rigorously audited and overseen by independent outside experts.”

“Society has hit pause on other technologies with potentially catastrophic effects on society,” the signers agreed, citing endeavors like human cloning, eugenics, and gain-of-function research in a footnote. “We can do so here.”

That pause didn’t happen, and critics like the University of Washington’s Emily Bender have called the letter itself an example of AI hype — the tendency to overstate systems’ true abilities and nearness to human cognition.

Support Undark Magazine

Undark is a non-profit, editorially independent magazine covering the complicated and often fractious intersection of science and society. If you would like to help support our journalism, please consider making a donation. All proceeds go directly to Undark’s editorial fund.

Still, government leaders should be concerned about negative reactions, said Boudreaux, the RAND researcher. “There’s a lot of questions and concerns about the role of AI, and it’s all the more important that the U.S. demonstrate its commitment to the responsible deployment of these technologies,” he said.

The idea of a rebellious drone killing its operator might fuel dystopian nightmares. And while that scenario may be something humans clearly want to avoid, national security AI can present more subtle ethical quandaries — particularly since the military operates according to a different set of rules.

For example, “There’s things like intelligence collection, which are considered acceptable behavior by nations,” said Neil Rowe, a professor of computer science at the Naval Postgraduate School. A country could surveil an embassy within its borders in accordance with the 1961 Vienna Convention, but tech companies are bound by a whole different set of regulations; Amazon’s Alexa can’t just record and store conversations it overhears without permission — at least if the company doesn’t want to get into legal trouble. And when a soldier kills a combatant in a military conflict, it’s considered to be a casualty, not a murder, according to the Law of Armed Conflict; exemptions to the United Nations Charter legally allow lethal force in certain circumstances.

“Ethics is about what values we have,” said Danks, the UCSD professor. “How we realize those values through our actions, both individual and collective.” In the national security world, he continues, people tend to agree about the values — safety, security, privacy, respect for human rights — but “there is some disagreement about how to reconcile conflicts between values.”

National security AI can present more subtle ethical quandaries — particularly since the military operates according to a different set of rules.

Danks is among a small community of researchers — including philosophers and computer scientists — who have spent years exploring those conflicts in the national security sector and trying to find potential solutions.

He first got involved in AI ethics and policy work in part because an algorithm he had helped develop to understand the structure of the human brain was likely being used within the intelligence community, because, he says, the brain’s internal communications resembled those between nodes of a terrorist cell. “That isn’t what we designed it for at all,” said Danks.

“I feel guilty that I wasn’t awake to it prior to this,” he added. “But it was an awakening that just because I know how I want to use an algorithm I develop, I can’t assume that that’s the only way it could be used. And so then what are my obligations as a researcher?”

Danks’ work in this realm began with a military focus and then, when he saw how much AI was shaping everyday life, also generalized out to things like autonomous cars. Today, his research tends to focus on issues like bias in algorithms, and transparency in AI’s “thinking.”

But, of course, there is no one AI and no one kind of thinking. There are, for instance, machine-learning algorithms that do pattern-recognition or prediction, and logical inference methods that simply provide yes-or-no answers given a set of facts. And Rowe contends that militaries have largely failed to separate what ethical use looks like for different kinds of algorithms, a gap he addressed in a 2022 paper published in Frontiers in Big Data.

One important ethical consideration that differs across AIs, Rowe writes, is whether a system can explain its decisions. If a computer decides that a truck is an enemy, for example, it should be able to identify which aspects of the truck led to that conclusion. “Usually if it’s a good explanation, everybody should be able to understand,” said Rowe.

In the “Where’s Waldo” kind of computer vision Probasco mentioned, for example, a system should be able to explain why it tagged a truck as military, or a jet as a “fighter.” A human could then review the tag and determine whether it was sufficient — or flawed. For example, for the truck identified as a military vehicle, the AI might explain its reasoning by pointing to its matching color and size. But, in reviewing that explanation, a human might see it failed to look at the license plate, tail number, or manufacturer logos that would reveal it to be a commercial model.

Neural networks, which are often used for facial recognition or other computer-vision tasks, can’t give those explanations well. That inability to reason out their response suggests, says Rowe, that these kinds of algorithms won’t lead to artificial general intelligence — the human-like kind — because humans can (usually) provide rationale. For both the ethical reasons, and for the potential limits to its generality, Rowe said, neural networks can be problematic for the military. The Army, the Air Force, and the Navy have all already embarked on neural-network projects.

For algorithm types that can explain themselves, Rowe suggests the military program them to display calculations relating to specific ethical concerns, like how many civilian casualties are expected from a given operation. Humans could then survey those variables, weigh them, and make a choice.

One important ethical consideration that differs across AIs, Neil Rowe writes, is whether a system can explain its decisions.

How variables get weighted will also come into play with, for example, AI pilots — as it does in autonomous cars. If, for example, the collision avoidance systems must choose between hitting a military aircraft from the aircraft’s own side, with a human aboard, or a private plane of foreign civilians, programmers need to think through what the “right” decision is in that case ahead of time. AI developers in the commercial sector have to ask similar questions about autonomous vehicles, for example. But in general, the military deals with life and death more often than private companies. “In the military context, I think it’s much more common that we’re using technology to help us make, as it were, impossible choices,” said Danks.

Of course, engaging in operations that make those tradeoffs at all is an ethical calculation all its own. As with the example above, some ethical frameworks maintain that humans should be kept in the loop, making the final calls on at least life-or-death decisions. But even that, says Rowe, doesn’t make AI use more straightforwardly ethical. Humans might have information or moral qualms that bots don’t, but the bots can synthesize more data, so they might understand things humans don’t. Humans also aren’t objective, famously, or may themselves be actively unethical.

AI, too, can have its own biases. Rowe’s paper cites a hypothetical system that uses U.S. data to visually identify “friendly” forces. In this case, it might find that friendlies tend to be tall, and so tag short people as enemies, or fail to tag tall adversaries as such. That could result in the deaths — or continued life — of unintended people, especially if lethal autonomous weapons systems were making the calls.

In this case, two things become clear: The military has an active interest in making its AI more objective, and the motivation isn’t just a goodness-of-heart pursuit: It’s to make offense and defense more accurate. “The most ethical thing is almost always not to be at war, right?” said Danks. “The problem is, given that we ended up in that situation, what do we do about it?”

There are efforts to define what ethical principles the DOD will adhere to when it comes to AI. The Defense Innovation Board, an independent advisory organization under the Defense Department that gives the military advice, in part on emerging technology, proposed a set of AI principles back in 2019. To prepare those, they held a series of public listening sessions — including at Carnegie Mellon University, where Danks was a department head at the time. “There was a real openness to the idea that they did not necessarily have all of the knowledge, or even perhaps much of the knowledge, when it came to issues of ethics, responsibility, trustworthiness and the like,” he said.

The DOD, following recommendations that emerged from the board and its research, then released AI ethics principles in 2020, including that systems be “traceable,” meaning that personnel would understand how the systems work, and have access to “transparent and auditable methodologies, data sources, and design procedure and documentation.”

The principles also state that AI must be governable — meaning a human can turn it off if it goes rogue (and tries, for instance, to kill its operator). “A lot of the devil’s in the details, but these are principles that if implemented successfully, would mitigate a good deal of the risks associated with AI,” said Boudreaux. But right now, overarching AI-specific guidelines for the Department of Defense as a whole are much more talk than walk: Although military contractors must comply with many general policies and practices for whatever they’re selling, a specific set of policies or practices that military AI developers need to adhere to are lacking, as is an agreement about how AI should be used in war.

Boudreaux notes that the DOD employs lawyers to make sure the U.S. is complying with international law, like the Geneva Conventions. But beyond global humanitarian protections like that, enforceable, international law specific to AI doesn’t really exist. NATO, like the U.S. military, has simply put out guidance in the form their own “Principles of Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence in Defence.” The document asks NATO countries and allies to consider principles like lawfulness, explainability, governability, and bias mitigation “a baseline for Allies as the use AI in the context of defence and security.”

Danks says it’s important to agree, internationally, not just on the principles but on how to turn them into practice and policy. “I think there are starting to be some of these discussions,” he said. “But they are still very, very early. And there certainly is, to my knowledge, no agreements that have been reached about agreed-upon standards that work internationally.”

“The most ethical thing is almost always not to be at war, right? The problem is, given that we ended up in that situation, what do we do about it?”

In 2022, Kathleen Hicks, the U.S. deputy secretary of defense, signed a document called the Responsible Artificial Intelligence Strategy and Implementation Pathway, which is one step toward turning principles into operation in the U.S. “I do think that it translates, but only with work,” said Danks.

At the Defense Innovation Unit, officials wanted to try to turn the principles into pragmatism. Since this is the DOD, that involved worksheets for projects, asking questions like “Have you clearly defined tasks?” They see this as a potential way to mitigate problems like bias. Take racial bias in facial recognition, says Bryce Goodman, chief strategist for AI and machine learning at the DOD. He says that’s often because developers haven’t tasked themselves with making their algorithm accurate across groups, rather than providing overall accuracy. In a dataset with 95 White soldiers and five Black soldiers, for instance, an AI system could technically be 95 percent accurate at recognizing faces — while failing to identify 100 percent of the Black faces.

“A lot of these kinds of headline-grabbing, ethical conundrums are mistakes that we see flow out of kind of sloppy project management and sloppy technical description,” said Goodman.

Internationally, the country is interested in achieving consensus on the ethics of military AI. At a conference in the Hague in February, the U.S. government launched an initiative intended to foster international AI cooperation, autonomous weapons systems, and responsibility among the world’s militaries. (An archived version of the framework noted that humans should retain control over nuclear weapons, not hand the buttons over to the bots; that statement did not appear in the final framework.)

But convincing unfriendly nations to agree to limit their technology, and so perhaps their power, isn’t simple. And competition could encourage the U.S. to accelerate development — perhaps bypassing safeguards along the way. The Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Research & Engineering at DOD did not respond to a request for comment on this point.

“There are these pressures to try to ensure that the U.S. is not at some sort of competitive disadvantage because it’s acting in a more restrictive way than its adversaries,” said Boudreaux.

A version of that dynamic is how the U.S. first started working on nuclear weapons: Scientists believed that Germany was working on an atomic bomb, and so the U.S. should get started too, so it could develop such a weapon first and have primacy. Today, Germany still doesn’t have any nuclear weapons of its own, while the U.S. has thousands.

Understanding what could happen in the future, especially without the right guardrails, is the point of thought exercises like the one that dreamed up an operator-killing drone.

“It’s really difficult to know what’s coming, and how to get ahead,” said Probasco.

A nice summary of “the story so far.” I can think of zero examples of systems (either spontaneously occurring or engineered) that neither entropically degrade, nor exhibit some tendency toward complex chaos, so I wonder why anyone ever expects “reliability” to emerge in AI. Every AI requires monitoring, every monitor needs watching, and so on…