A doctor’s memoir can be a tricky balancing act. Too much science, and the personal journey risks fading into the background; too much memoir, and the work that made the physician noteworthy can feel tacked on or underdeveloped. It’s a rare writer — think Abraham Verghese or Atul Gawande — who can pull it off seamlessly.

In “The Face Laughs While the Brain Cries: The Education of a Doctor,” Stephen L. Hauser, the director of the Weill Institute for Neurosciences and a neurology professor at the University of California, San Francisco, manages for the most part to walk the line, even if the focus on his formative years at times obscures his remarkable work in understanding and treating multiple sclerosis, or MS, a chronic disorder that affects nearly 1 million Americans.

BOOK REVIEW — “The Face Laughs While the Brain Cries: The Education of a Doctor,” by Stephen L. Hauser (St. Martin’s Press, 304 pages).

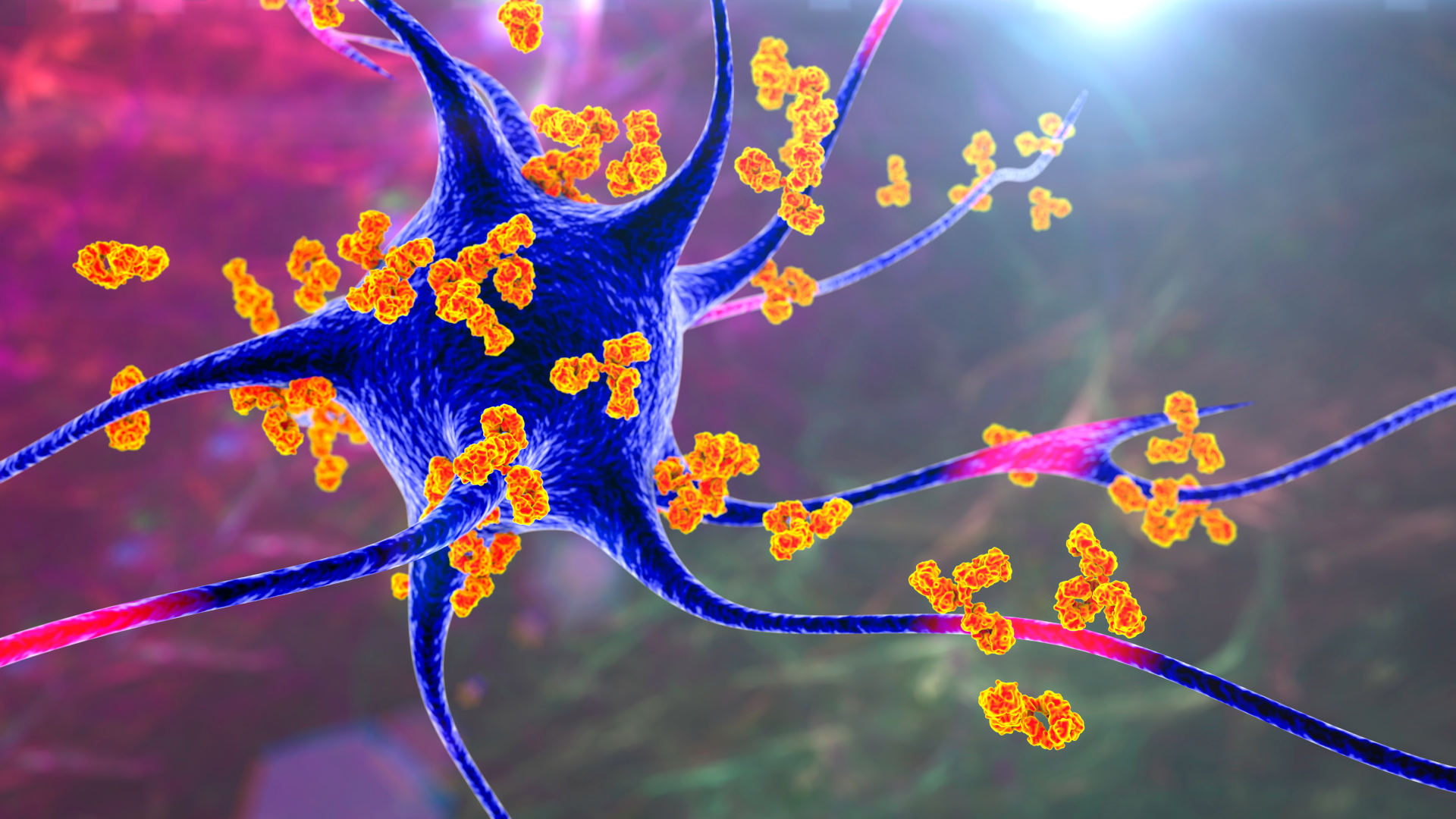

As a neuroimmunologist, Hauser studies both the nervous and immune systems, and how the two affect each other. “Multiple sclerosis is a disease of the immune system and the brain,” Hauser writes. “The immune system, designed to protect us against invading microbes, misidentifies nerve cells and their myelin coverings as foreign. This leads to an autoimmune attack — the body turning against itself.”

As the disease progresses, the nerve damage can lead to an unpredictable range of symptoms, including numbness or weakness on one side of the body, vertigo, slurred speech, fatigue, and double vision. For some people, the disease steadily progresses; others have periods of remission. Since there is no cure, treatment focuses instead on symptom management, speeding up recovery time from attacks, and slowing disease progression.

In addition to exploring the genetic roots of MS, Hauser and his team identified the critical role of B cells in attacking nerve cells, leading to the development of immunosuppressive drugs that target and destroy the B cells, thus reducing inflammation, slowing down nerve damage, and easing symptoms. These B-cell therapies were the first to be effective in treating progressive MS, and have been enormously beneficial for those living with the disease.

While the book’s title refers to one of the many symptoms of MS — the discrepancy between facial expressions and the intended emotion — it’s the subtitle that gives away Hauser’s true agenda. As he writes early on, “These two subjects — troubles with the immune system and troubles with the brain — have been on my mind for as long as I can remember. I’m always trying to make connections between early events and my later choices in life, lining them up to create a coherent story.”

Prominent among his formative experiences growing up in the 1950s and ’60s was his relationship with his younger brother, who was born “severely handicapped, both mentally and physically,” and who died at an early age. He also tells of a close childhood friend who died of a brain tumor, and of his own health troubles: “My own immune system has always been overactive,” he writes. “Asthma, allergies, and eczema have been my constant companions.”

Support Undark MagazineUndark is a non-profit, editorially independent magazine covering the complicated and often fractious intersection of science and society. If you would like to help support our journalism, please consider making a donation. All proceeds go directly to Undark’s editorial fund.

|

These moments, among others, helped sow the seeds for Hauser’s fascination with medicine and the immune system in particular. “Of all our body’s tissues, our immune system is most dependent on the microscopic life forms that cohabitate with us. We’ve been engineered to operate in an equatorial forest of bugs. Without them, our immune defenses become soft, ineffective, unsuccessful.” Hauser’s life work, in effect, has been exploring this forest.

The book begins with a case study of Andrea, a patient of Hauser’s during his residency at Massachusetts General Hospital in the 1970s. A Harvard Law graduate with a promising start to a career in government service, she started to exhibit bizarre behavior and neurological symptoms that would eventually be diagnosed as MS. Hauser cared for her for weeks before she left for a rehab center. At Andrea’s bridal shower several months later, her family gave Hauser a glass paperweight of a turtle as a gift to let him know how he had touched their lives. That simple gesture, he writes, inspired him to make MS the focus of his career.

While a resident at New York Hospital, Hauser’s grandfather was admitted with late-stage Parkinson’s disease and heart issues. It proved to be a traumatic experience for his grandfather, with constant interruptions to sleep, an unfamiliar environment, patronizing medical staff, and impersonal treatment. Hauser saw all of this, and his grandfather eventually signed himself out against medical advice. It would also be the last time he agreed to be hospitalized. Shortly after, the grandfather told Hauser he was stopping his Parkinson’s medications: “I think that the dehumanizing experience in my hospital, under ‘the very best possible’ care by my colleagues and friends, hastened his decision to die on his own terms, dignity intact.” His grandfather died a few days later. “The purpose of medicine is to treat the person, not the illness,” was the lesson Hauser took away. “The clinician must learn to see through the eyes of the patient.”

Personal moments like these are vividly told, and Hauser is honest and self-effacing about his successes and and failures in the lab and with his patients. But his groundbreaking discoveries in MS treatment are mostly relegated to the final few chapters. He does cover the most important moments in his career, including the rocky clinical trials for the first-generation drug rituximab and his role in the development of the breakthrough treatment ocrelizumab (sold under the brand name Ocrevus), approved by the FDA in 2017, but these sections often feel rushed. And when he does delve into the science, he tends to quickly switch gears to another anecdote or discussion of the vagaries of the pharmaceutical industry or his time serving on the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues during the Obama administration.

It’s a compelling memoir, if somewhat frustrating for readers interested in the deeper science behind MS. At the end, Hauser acknowledges that his original plan was to write about a medical discovery (ostensibly ocrelizumab), but as the book progressed it became more about his overall life and career. And to be fair, it does live up to its subtitle: This is a candid book about how a physician embarked on his chosen path, the patients and family who guided him along the way, and, above all, the battle to cure a confounding disease.

“The battle is not yet won, but all of the pieces are in place to soon reach the finish line — a cure for MS,” he writes. “The future is filled with promise.”

Jaime Herndon is a science writer and editor whose work has appeared in Book Riot, goEast/Eastern Mountain Sports, Healthline, and American Scientist, among other publications.

I was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis when I was 52 years old 4 years ago. The Bafiertam did very little to help me. The medical team did even less. My decline was rapid and devastating. It was muscle weakness at first, then my hands and tremors. Last year, a family friend told us about Natural Herbs Centre and their successful MS Ayurveda TREATMENT, we visited their website natural herbs centre. com and ordered their Multiple Sclerosis Ayurveda protocol, i am happy to report the treatment effectively treated and reversed my Multiple Sclerosis, most of my symptoms stopped, I’m able to walk and my writing is becoming great, sleep well and exercise regularly. I’m active now, I can personally vouch for these remedy but you would probably need to decide what works best for you🧡.