In June 1845, J. Marion Sims, a 33-year-old surgeon in Montgomery, Alabama, was called to the bedside of a pregnant Black teenager at a nearby plantation. According to Sims, the patient, named Anarcha, had been in labor for an excruciating 72 hours; the baby was wedged in her pelvis, her contractions had almost ceased, and if nothing was done, both would die.

Sims — who would go on to be regarded as the father of modern gynecology and one of the most highly recognized doctors in America by the time of his death in 1883 — wrote that he pulled the infant, who did not survive, out with forceps. But the girl’s vaginal canal had already been seriously injured from the relentless pressure of the baby’s body, and days later, dead tissue began to slough off, leaving two openings, one that exposed her bladder, and one her rectum. Urine, stool, and gas now flowed uncontrollably into and out of her vagina.

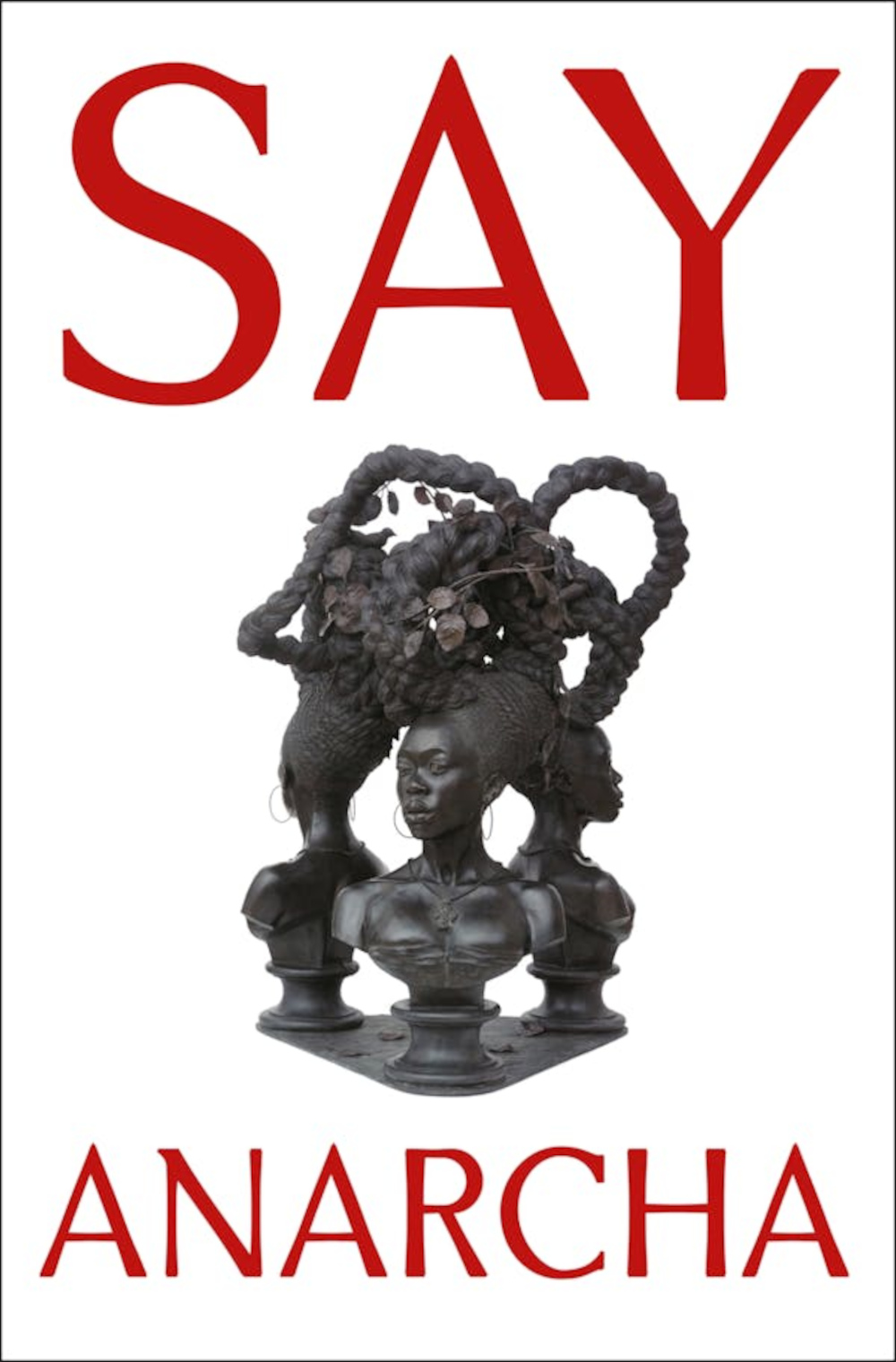

BOOK REVIEW — “Say Anarcha: A Young Woman, a Devious Surgeon, and the Harrowing Birth of Modern Women’s Health,” by J.C. Hallman (Henry Holt and Co., 528 pages).

Anarcha’s plight is described in “Say Anarcha: A Young Woman, a Devious Surgeon, and the Harrowing Birth of Modern Women’s Health,” a new book by J.C. Hallman billed by the author as “speculative nonfiction.” Hallman’s work is a massive but deeply flawed undertaking that is best understood alongside other major medical histories like the 2007 tour de force, “Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present,” by medical ethicist Harriet Washington and the 2018 “Tears for My Sisters: The Tragedy of Obstetric Fistula,” by L. Lewis Wall, a retired obstetrician-gynecologist and medical anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

Equally important is the lived experience of Black women, including a remarkable 2018 book of poetry, “Anarcha Speaks: A History in Poems,” by Dominique Christina, which details in lyric, searing images the same events from both Sims’ view and Anarcha’s. In large part these books seem faithful to the letter and the spirit of history, where Hallman’s at times does not. Hallman writes that the Anarcha presented in his book is a combination of “direct evidence of her existence,” and “probabilities, inferences, informed speculation, and guesswork.”

The injury Anarcha suffered during childbirth is called a vesico-vaginal fistula (or recto-vaginal fistula if the opening is to the rectum), a devastating condition that is rare today in wealthy countries but was not uncommon in the 1800s, before the advent of modern anesthesia and advancements in cesarean sections. During that time, it more often struck enslaved Black women due to malnourishment and pregnancies at a young age.

According to Hallman, Sims was single-mindedly obsessed with curing the affliction, and spent several years perfecting his techniques with repeated surgeries on at least seven other enslaved Black women and teenagers (though the exact number is unknown) that he housed in a small “hospital” he had built behind his own home. Fistulas took everything from their sufferers, who bore great pain and became social pariahs. “Clearly,” writes Hallman, imagining Sims’ voice, “honor awaited the man who could cure fistula once and for all.”

For nearly four years, Sims carried out these operations without anesthesia, although ether anesthesia was first demonstrated 10 months into his work; many doctors were slow to adopt it, wary of overdosing or underdosing. During this time, he invented a version of the speculum, pioneered the use of silver sutures to prevent infection, and designed slender perforated lead bars to serve as clamps, along with an S-shaped silver catheter with slits and holes that drained the bladder (which allowed sutures to better heal after fistula surgery).

His early experiments were awful failures, leading to infection and even sepsis, and though later surgeries slowly shrank the fistulas’ size, these improvements offered hope but little clinical reprieve, since urine can flow easily through small openings.

In 1849, he claimed to have finally succeeded in closing Anarcha’s fistulas. It was her 30th surgery and the beginning of Sims’ ascent to fame, leading to his eventual founding of the first hospital for women in New York City, and culminating in his election in 1876 to president of the American Medical Association.

Hallman notes in his introduction that portraits at the time praised the doctor exuberantly: “Then, like a meteor, appeared the genius of Sims!” one medical journal proclaimed. But by the late 20th century, Sims’ experimentation on Black bodies without anesthesia had come to be seen as ruthless, dehumanizing, and part of the terrible legacy of medical exploitation of Black people, which includes the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and the complicated history of Henrietta Lacks. “Marion Sims epitomizes the two faces — one benign, one malevolent — of American medical research,” according to Washington in “Medical Apartheid.”

As Sims fell from grace, Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey, three young people mentioned by name in the surgeon’s recounting, began to emerge from obscurity, honored today in an imposing monument called The Mothers of Gynecology, by artist Michelle Browder, with the help of 15 volunteers, in Montgomery.

J. Marion Sims performed experimental surgeries on several enslaved Black women and teenagers. His method, he claimed, ultimately cured them of the terrible condition. He went on to become one of the most highly recognized doctors in America.

Visual: Wellcome Collection

It is into this fraught history that Hallman strides. In telling Sims’ story, Hallman draws on a cornucopia of original sources, ranging from the surgeon’s own posthumous autobiography, “The Story of My Life,” to his correspondence, the records of peers and biographers, and numerous journal articles, among other documents. The footprints Anarcha left behind are scarce, though Hallman seems to have traced her wherever she could be found, and even landed at her gravestone in a forest in Virginia. Nonetheless, he admits: “Say Anarcha is a book about a ghost.”

To fill out Anarcha’s story and voice, Hallman, whose previous works have creatively tested nonfiction categories, creates a composite portrait drawn from events and memories recorded in 55 volumes of interviews with formerly enslaved people compiled by the Federal Writers’ Project from 1936 to 1938. He also spent 10 weeks in Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Uganda, at women’s hospitals for vesico-vaginal fistulas. Yet in the end, he uses the novelist’s art to create a character, putting his book squarely in the tradition of historical novels, which blend invention and solid historical fact.

Hallman does provide an extensive online bibliography, which in itself is worth the price of entry, for lay readers and scholars alike: Annotated page by page, and available online at his Anarcha Archive, it offers a motherlode of original photos, letters, and documents.

He also does a thorough job of detailing the surgeon’s life, though the Sims that emerges is callously ambitious, and his successes and inventions are portrayed as calculated stepping stones to fame, creating a truly repugnant man: “Cancer was even better than fistula — the fact that it threatened life made for more agreeable patients.”

Hallman’s Anarcha, in contrast, is a braid of talented nurse and abused illiterate. His frequent references to “cursed women,” and their “holes” and “stench,” over-reaches and, to this reader at least, lacks the deeply empathetic witnessing seen in “Tears for My Sisters.”

A bigger concern is the way Hallman ventriloquizes Anarcha’s ordeal. When a surgeon in Virginia gathers colleagues around to describe Anarcha’s newly reopened fistula (either due to failure of her previous surgeries, or to childbirth reopening the fistulas, Hallman writes), he imagines the surgeon saying that “her holes were thickened and indurated from all the previous experiments,” and writes that “Anarcha didn’t know what indurated meant, but it didn’t sound like a good word.”

A physician speaking to colleagues would likely have used the medical term fistula rather than holes; moreover, Sims trained Anarcha and the other enslaved women and teenagers to be his surgical nurses. They “knew more about the repair of obstetrical fistulae than most American doctors during the mid to late 1840s,” according to historian Deirdre Cooper Owens, in the 2017 book “Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology.” In other words, Anarcha was not a medical naif.

In one troubling fictional scene, Anarcha is repeatedly raped from behind by a stranger in a dark barn, leading to that first pregnancy: The rape is described graphically but Hallman writes that although “every part of her fired and pained,” she “did not scream like those who were whipped.” Later, Hallman imagines that Sims “liked operating on her because” she “never moved or made a sound, though the pain was fierce and cut down into her soul.”

Why doesn’t she move or make a sound when raped or operated on? Hallman’s bibliography explains this choice by contrasting Sims’ description of Anarcha with his observations of Lucy and Betsey’s pain. But are we to trust Sims, the unreliable narrator of his own life? Hallman doesn’t trust him on so much else. And though Hallman demurs in his bibliographical note, writing that there is no reason to believe that Anarcha’s “stoicism had anything to do with her race,” his florid descriptions and invented scenes go so much farther than Sims’ clinical notes. In spite of his denial, Hallman seems to have fallen prey to the same fiction Sims did, that Black people don’t feel pain or shame the way White people do — a fiction that persists in the present day.

These flaws run through “Say Anarcha” and recapitulate the harms already endured by these Black women and teenagers. Even so, the book is absorbing in its details and will hopefully bring more attention to this chapter in medical history, as well as the suffering that continues today in parts of Africa where obstetric fistula are not uncommon, which Hallman details in his afterword.

In addition, scholars can access Sims’ patient casebooks from the 1850s onward, after his surgeries on Anarcha, which have been digitized at the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives at Mount Sinai.

And if you are seeking what might be the closest evocation of Anarcha’s long-buried voice, you need go no further than Dominique Christina’s 2018 poem, “Anarcha Will Speak and It Will Be So”: “i, a salted wound./i the upset of everything,/unholy,/this.”

UPDATE: A previous version of this review appeared to suggest that the terms “fistula” and “indurated” are interchangeable; they are not. The text has been updated for clarification. Additionally, the name of the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives was incomplete and has been updated.

Jill Neimark is a writer based in Macon, Georgia, whose work has been featured in Discover, Scientific American, Science, Nautilus, Aeon, NPR, Quartz, Psychology Today, and The New York Times. Her latest book is “The Hugging Tree” (Magination Press).