In a Tipster’s Note, a View of Science Publishing’s Achilles Heel

On paper, data scientist Gunasekaran Manogaran has had a stellar scientific career. He earned an award as a young researcher from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and landed a series of postdoctoral and visiting researcher positions at universities in the U.S., including the University of California, Davis; Gannon University in Pennsylvania; and Howard University in Washington, D.C. His h-index — a measure of a researcher’s impact and productivity — is 60, a number that by one model would mark him as “truly unique” if achieved within 20 years. He did it in fewer than 10.

Emails obtained by Undark, however, suggest some researchers have doubts about his publishing record. The correspondence includes an initial message from someone claiming to have previously worked with Manogaran. It was sent to some 40 editors of scientific journals, many owned by major scientific publishers: Elsevier, Springer Nature, Wiley, and Taylor & Francis among them.

The sender alleges that Manogaran and others run a research paper publishing scam — one that both generates revenues and artificially burnishes the scientific bona fides of individual and institutional participants. In particular, the alleged scheme targets what are known in the scientific publishing industry as “special issues” — self-contained special editions that are not part of a journal’s regular publishing schedule, typically focused on a single topic or theme.

The email, dated April 12, 2022, informs the journal editors that they may have partnered with members of this alleged scheme and urges them to take action. “If you don’t do that there would be a next group doing the same scam in name of different persons,” the email states.

Multiple attempts to reach the sender of these allegations, who used the name Aishwarya Swaminathan, were unsuccessful, and Undark has not been able to independently verify the purported tipster’s identity. When initially contacted for this article, Manogaran vigorously disputed the broad claims being made against him. “I have done collaborative research work with many professors and this may be wrongly misunderstood and misjudged,” he wrote in an email message to Undark. He called the allegations “false information.”

Manogaran has had his research flagged before: According to Retraction Watch, an organization that monitors and reports on the retraction of scientific papers, Manogaran has more than a dozen recent retractions — often attributed to questions about authorship or the veracity of peer review.

Additionally, on his LinkedIn page, Manogaran is listed as a visiting researcher at the Francisco José de Caldas District University. The university, however, denied any affiliation. Manogaran’s profile states that he was at the University of California, Davis, and one website lists him as an alumni of the university’s Data Lab, but Pamela Reynolds, associate director of the lab, said he was never a member. Howard could not confirm whether Manogaran had attended and Gannon did not respond to emails or calls from Undark.

Manogaran declined requests for a more detailed conversation regarding the full extent of claims made in the April 2022 email, saying that he was going on an extended vacation.

But discussions with numerous editors and publishers at the scientific journals allegedly targeted, as well as with independent experts in the scientific publishing realm, lend support to the purported whistleblower’s claims. If the allegations are true, the problems with Manogaran’s work, alongside that of other alleged collaborators, run much deeper. At least 60 journal issues — containing hundreds, potentially thousands of scientific articles — are still online, edited or authored by researchers whose names are associated with the scheme, said Nick Wise, a research associate at the University of Cambridge, who has been investigating the problem and who shared the emails with Undark. He emphasized that some journals published multiple special issues that may have been affected.

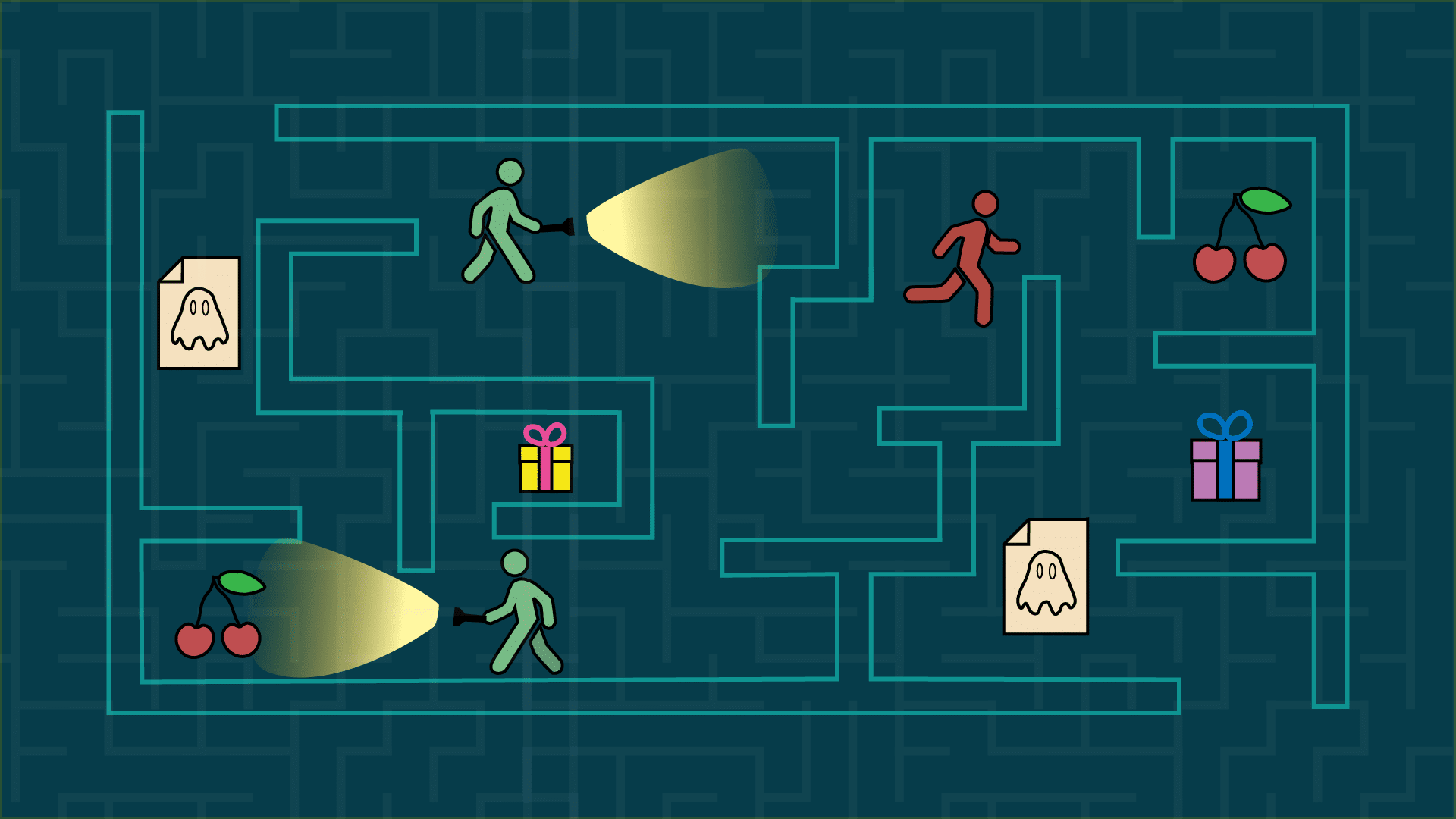

Wise referred to the alleged scheme as a “paper mill”: a loose network of authors and editors producing and selling dubious or low-quality scientific articles. “I know that this paper mill targeted, and continues to target, all the publishers,” Wise said. The scientific publishing industry, with its unique structure and outsized influence, is a frequent and all-too-easy target for such operations, Wise and other critics say. And they note that the industry has few incentives to aggressively police the problem, given the substantial profits earned by major publishers.

And yet, the impact of such purported schemes can be consequential: While the majority of deceptive or low-quality work circulates in little-known journals, experts note that the cumulative effect can create a disadvantage for all academics who play by the rules. Such alleged schemes ultimately erode public trust in science itself. In cases where these articles are about topics of public concern, like Covid-19, drug development, or cancer research, these efforts may stall critical research or otherwise put human health at risk.

“This case is really terrible,” said Izabela Zych, editor in chief of Aggression and Violent Behavior, which was identified by Undark as one of the journals duped by the alleged publishing scheme. And this case is just one of many other, much larger, operations affecting the publishing industry, said Jay Flynn, executive vice president and manager of Wiley’s research division. Flynn has seen paper mill-like operations at Wiley involving up to 100 individuals.

“If this continues,” the tipster wrote, “after a decade the whole scientific knowledge and ethics will be damaged.”

Historically, special issues have served a unique role in academic research by allowing academics to zoom in on particularly hot topics and explore different lines of inquiry. Special issues have also helped to bring in revenue for those who publish them — in part thanks to fees that authors pay in exchange for the journals’ making their papers openly available to the public. (In early May, dozens of scientists resigned from the editorial board of an Elsevier journal to protest its high publication fees.)

Critics say special issues are prone to being hacked or otherwise manipulated because they are typically run by non-staff “guest editors.”

While these guest editors, who are typically not paid, are often identified and approached by the journal’s regular editors to manage a themed issue, researchers can also bring an idea for a special issue topic to the journal — and the April 2022 email describes an alleged scheme that exploits this process. According to the tipster, organizers of the operation first used a website to take bulk orders from researchers in countries like China and Taiwan, where Ph.D. students and medical doctors have long faced pressure to publish.

The organizers, the tipster continued, then contacted dozens, sometimes hundreds, of academic journals and proposed a special issue. If a journal took the bait, it sometimes assigned one or more members of the scheme to serve as guest editors. This would effectively give the interlopers carte blanche to write and respond to peer reviews and to cite themselves generously. Under such circumstances, guest editors can basically publish anything, said Dorothy Bishop, an emeritus professor of developmental neuropsychology at the University of Oxford in the U.K., who also writes about dubious scientific publications.

The alleged paper mill itself, the tipster suggested, could have launched during Manogaran’s time at the Vellore Institute of Technology, a private research university in South India, where Manogaran obtained his Ph.D. Undark reached out to VIT to share the allegations made in the tipster’s email — including the suggestion that some of its alumni were part of an alleged publishing scheme. “We do not entertain any kind of such unethical practices under any circumstances,” said Partha Sharathi Mallick, pro-vice chancellor at the institute, adding that he had asked the university to investigate the allegations and submit a formal report. “We will surely take necessary actions in case any VIT staff are involved.”

Mallick confirmed that Manogaran was a VIT alumni but said the university has not been in contact with him.

Vicente García Díaz, an associate professor of computer science at Spain’s University of Oviedo, was identified in the April 2022 email as a collaborator in the alleged scheme. García Díaz was initially set to oversee a 19-paper special issue for the journal Ecological Informatics — but according to the journal’s editor in chief, George Arhonditsis, the arrangement was dissolved after the allegations were levelled by the tipster.

When Undark contacted García Díaz, he said that the Ecological Informatics special issue — along with about 20 others — had actually been managed by Manogaran.

In theory, using the name of a real researcher as an alias would allow Manogaran to boost both his own and the cooperating researcher’s scientific profile without detection, because he could control which papers were included in the special issue, and whose work those papers cited. Text messages between the two researchers, obtained by Undark, show that Manogaran approached García Díaz by boasting about having already guest edited 25 special issues.

As a result, in just two years, Manogaran said he had managed to boost the number of times other articles cited his work by 3,000. “My objective is to collaborate with various international professors and help them to improve their profile and also I can use them to make this happen,” read one of Manogaran’s texts.

García Díaz said Manogaran has run about 20 special issues under his name over the years. Manogaran also included García Díaz’s name on papers written by his colleagues. García Díaz said he did not object. “I’m not a dishonest person, at best I’m a stupid who believed in someone who shouldn’t,” Garcia Diaz wrote in an email message to Undark.

In the past five years, García Díaz and seven other researchers who allegedly collaborated with Manogaran have experienced a rapid boom in their citation numbers.

When Undark told Arhonditsis, the journal’s editor, that García Díaz admitted the special issue was managed by Manogaran, the editor said he would raise the problem with the journal’s publisher, Elsevier, to decide on how to proceed.

“Needless to say that if this is indeed what he did, then we need to take action.”

Undark has confirmed that Manogaran worked with other people listed on the April 2022 email — including Seifedine Kadry, a professor of data science at Noroff University College, in Oslo, Norway. Kadry said the two struck up a collaboration given their mutual interests in data science, and that they agreed to work together on books, journals, conferences, and special issues.

Everything seemed fine for Kadry until he noticed that a lot of Manogaran’s work was being retracted. He also realized that Manogaran had tried opening up special issues on topics that were irrelevant to either of their fields of expertise, including sports. Kadry decided to end the partnership.

Kadry said he never profited off the endeavor, nor did he observe Manogaran participating in activities suggestive of a paper mill.

Kadry did, however, guest edit a special issue in the journal Information Processing & Management that raised serious concerns, according to Jim Jansen, its editor. According to emails shared by Kadry, Jansen had expressed concern that Kadry was recommending acceptance for an abnormally high number of articles. Jansen also questioned the legitimacy of the peer review process being deployed.

After warning Kadry three times, Jansen says he decided to cancel the issue. He had a similar experience, he said, with another special issue guest-edited by someone listed in the April 2022 email. In this case, the problematic behavior included buying and selling of articles, Jansen said, but he declined to elaborate.

A similar story came from Ching-Hsien Hsu, a professor of engineering at Asia University and National Chung Cheng University, both in Taiwan, who, like Kadry and García Díaz, was named as a collaborator in the tipster’s April 2022 email. Hsu said he never met Manogaran in person but agreed to collaborate with him in opening up special issues. Hsu’s condition was that Manogaran would inform Hsu before submitting a proposal under Hsu’s name.

But this didn’t happen, said Hsu. “Obviously I was not aware/or was skipped for many projects,” Hsu wrote in an email to Undark. Nevertheless, he said he tried his best to maintain quality standards for articles that he knew named him as an author. “I believe that I tried very very hard to control the quality of editorial review process,” he wrote.

Hsu currently has at least seven retractions, according to Retraction Watch’s database.

Whatever the merits of the allegations surrounding Manogaran and his collaborators, ample evidence suggests a systemic problem in the publishing industry and its recent expansion into special issues. The problem affects publishers at all levels of the industry, including respected and established houses like Elsevier and Wiley. It also extends to newer players, including publishers of freely available, open-access online journals such as Frontiers, MDPI, and Hindawi, which was acquired by the publisher Wiley in 2021.

Of these, Bishop says it’s a common perception that all three publishers have made special issues an important part of their business model, but none quite as much as MDPI, which now says it’s the biggest publisher of open-access articles in the world. In 2013, the company published nearly 400 special issues; a decade later, it opened up nearly 56,000. MDPI’s revenues have also exploded from around $15 million per year in 2015 to more than $300 million in 2021, according to some estimates. The rejection rate for papers published at MDPI journals has also been decreasing, even as the time between submission and publication has shrunk — suggesting to some critics that quantity is taking precedence over quality.

Manogaran was recently recognized as one of MDPI’s top 1 percent most frequently cited researchers from 2011 to 2021.

Meanwhile, scientific journals are famously slow to respond to articles flagged as problematic, critics argue. As of this spring, at least three major publishers — Springer Nature, Taylor & Francis, and Wiley — were still conducting investigations into the alleged paper mill identified by the tipster’s email.

The Elsevier publication Aggression and Violent Behavior was identified by Undark as one of the journals duped by the alleged publishing scheme. After two of the journal’s special issues were investigated by Elsevier, 69 articles were retracted.

When Elsevier conducted its investigation of two special issues published by the journal Aggression and Violent Behavior, it found evidence of a severely compromised peer review system, nonsensical figures, and authors with little to no scientific track record. “Perhaps too much faith was given to the Guest Editors,” wrote Kiran Dhaliwal, global press communications manager for Elsevier, in an email. The journal mentioned three guest editors responsible for these issues, one of whom was García Díaz. García Díaz said Manogaran ran one special issue under his name.

The journal has since retracted all 69 articles they deemed to have been affected.

The main reason for the generally sluggish response, critics suspect, boils down to money. “Scientific publishing is like a very strange entity making lots of money with nobody asking a lot of critical questions,” said Elisabeth Bik, a microbiologist who also consults on issues of integrity in science. Journals don’t always prioritize quality control and will sometimes accept sub-standard articles. Then, when people complain about these articles, Bik said, the publishers “look the other way.”

Resources also play a role: Publishers have to initiate investigations, which often involves looking into articles on a case-by-case basis — a process that can take months, if not years, to complete. When publishers do make the retraction, they often provide little information about the nature of the problem, making it difficult for journals to learn from each other’s lapses. All in all, said Bishop, the system just isn’t built to deal with the gargantuan size of the problem.

“This is a system that’s set up for the occasional bad apple,” Bishop said. “But it’s not set up to deal with this tsunami of complete rubbish that is being pumped into these journals at scale.”

A recent effort by publishers and the International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers, an international trade group, aims to provide editors with tools to check articles for evidence of paper mill involvement and simultaneous submission to multiple journals, among other issues.

But even with such initiatives ongoing, stakeholders on social media accuse MDPI in particular of sloppy reviewing practices, and they have criticized the publisher for repeatedly inviting researchers to guest edit special issues, even when it was outside their field of expertise. Several editors of MDPI journals have resigned in protest, and Web of Science, a platform for indexing scientific journals, recently decided to de-list 82 journals, one of which is the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health — MDPI’s largest in terms of articles published.

“We want to assure you that the risk of publishing unreliable and unscientific content is not related to Special Issues,” said Giulia Stefenelli, chair of the scientific board at MDPI, adding that special issues undergo exactly the same peer review process as regular issues. Still, she admits that the publishing industry is facing hurdles. “At MDPI, we are aware of the publication ethics and research integrity challenges facing the publishing industry as a whole.”

As problematic as publishers like MDPI may be, some argue that their existence is fundamental to mitigating research inequality. Many researchers in the Global South face barriers to publishing in prestigious journals due to high costs, biases, and lack of resources. In a Twitter thread from March, Ana Marcia de Sá Guimarães, an assistant professor of biomedical sciences at the University of Sao Paulo, acknowledged that while publishers like MDPI and Frontiers have engaged in questionable reviewing practices, they have also provided more opportunities to non-Western researchers to publish. She added that they tend to be cheaper, more inclusive, and are generally well-recognized abroad.

Hindawi reveals a similar story. Prior to being acquired by the publisher Wiley in 2021, Hindawi was considered by some to be a respectable publisher. In recent years, however, its journals have been inundated with articles that show evident traces of paper mills in action.

Bishop conducted an analysis of all Hindawi journals published in 2022 and found that editors of special issues tended to process papers much faster than the norm. The quality in Hindawi special issues dropped so low that Wiley temporarily suspended their publication, leading to a $9 million loss in revenue in a single quarter.

“Wiley takes full responsibility for the content we publish across our portfolio,” wrote Flynn, the Wiley research division executive vice president and manager, in an email to Undark. By the end of April of this year, the publisher had retracted 1,700 articles. “We view this as a major threat to the ecosystem overall,” he added in a phone call. This problem can “migrate from one publisher to another to another to another,” he said.

Obtaining hard-proof that articles come from paper-generation operations can be tricky. Such schemes, Bishop said, often operate from false email addresses and pseudonyms. But evidence of their activities can be found on obscure websites that claim to offer “paper publishing services” or social media posts openly advertising the sale of authorships for particular journals. The strongest evidence that these studies originate from paper mill organizations, however, is the content itself.

“Some of the content is utterly nonsensical,” Bishop said. “There’s no way this is peer reviewed and it’s often completely unrelated to the topic of the journal or the special issue. It’s crazy stuff.”

Vicente García Díaz was initially set to oversee a special issue for the journal Ecological Informatics, but the arrangement dissolved after the email tipster’s allegations came to light.

Some cases are absurd, like a 2021 special issue published in the Arabian Journal of Geosciences containing 44 now-retracted articles linking aerobics and dance training, among other topics, with geosciences. Others raise eyebrows, like an article allegedly written by an author with the School of Marxism at Beijing Information Science & Technology University, for a special issue on human cognition and artificial intelligence in health care, which was received and accepted within 24 hours.

In the vast majority of instances, such low-quality papers appear in low-ranking journals that many researchers don’t necessarily read. “Some of these journals are what I think of as write-only journals — they’re not intended to be read at all,” said David Bimler, a retired psychologist previously based at Massey University in Palmerston North, New Zealand, who now dedicates his time to tracking problems in scientific publishing.

But these publications can still have consequences. After burnishing their CVs with dubious credentials, some alleged paper mill employees have gone on to assume permanent editorial positions at scientific journals, said Alexander Magazinov, a software engineer based in Kazakhstan, who also dedicates himself to watchdogging the scientific publishing industry.

As an example, he said Masoud Afrand, an assistant professor of engineering at the Islamic Azad University in Iran, was likely part of a paper mill operation for a special issue in Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences, where Afrand was cited over 130 times. Afrand is now an editorial board member for Scientific Reports articles in mechanical engineering.

Afrand did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

[Update: After publication of this article, Afrand’s name and affiliation were scrubbed from the Scientific Reports webpage listing editorial board members. The publication’s chief editor suggested that the listing was an oversight, and that Scientific Reports had “parted ways” with Afrand earlier in the year, due to detected “irregularities” in the researcher’s handling of papers. Afrand also subsequently resigned from the board of another journal in response to questions raised by Undark’s reporting. Read more at Retraction Watch here and here.]

The products of paper mills and other low-quality work can also pose a direct risk to human health. One special issue on Covid-19 included a now-retracted article claiming that vaccines killed five times more people over the age of 65 than they saved. In a preprint article, scientists found that 3 to 4 percent of all DNA sequences assessed in two leading cancer journals were flawed, potentially due to paper mill activity. These included at least eight articles in two special collections. The consequences of such mistakes could range from benign unexplained results to potentially stalling progress on research of global concern — and not just for health care.

“It impacts health care policy, it impacts energy policy, it impacts people’s careers, it impacts a broad swath of the work done in service of the human project,” said Flynn.

Nick Wise, meanwhile, said he suspects that the alleged publishing syndicate identified in the April 2022 email is still active — though he added that it’s impossible to know which researchers are complicit, and which are unwitting participants. Either way, Wise suggested the consequences of these sorts of operations cannot be underestimated. They undermine both “science and scientists,” he said.

Jonathan Moens is a freelance journalist based in Rome. His work has appeared in the New York Times, National Geographic, and The Atlantic, among other publications.

This story was produced in collaboration with

This story was produced in collaboration with

Alexander Magazinov goes around and calls every good researcher papermill. Kazakhstan court issued an arrest for him, but he had never entered Kazakhstan. Alexander Magazinov was inviolved in Vickers scandal for manipulating citations and blaming 1500 researchers using his 43 Pubpeer accounts to control university rankings and international collaboration.

Priyan Malarvizhi Kumar, Gannon University should be investigated in this case as he is the main collaborator with Gunasekaran Manogaran and executed several Special Issues in numerous journals and both had sudden spike in citations.

Priyan Malarvizhi Kumar received his PhD from VIT University under the guidance of Usha Devi Gandhi and both have several retractions. Priyan and Gunasekaran ran several Special issues together and artificially inflated their citations. It seems Priyan Malarvizhi Kumar is currently working in University of North Texas USA according to his google scholar profile. But Gunasekaran and Priyan deactivate their google scholar, research gate and Linkedin profiles whenever they got problems. I am curious how an University in USA offering job to Priyan without any clear background checking. Priyan has several retractions and violations; even her PhD supervisor also. One can do a simple google search to identify these but Universities which provide jobs are not doing this. It is obvious that these special issue scammers are basically from India (Mostly southern part). Indian educational institutions has no proper channels to monitor these research ethics scams and so these kind of scams in scientific community occur frequently. VIT Vellore is a kind of institution which compels faculties to publish papers in all possible manners and want to get the reputation/ranking and so these kind of scammers emerge. Even after several retractions from VIT University, the institution will not take necessary steps to solve these issues but tries to sugarcoat things. Institutions in India lack proper research ethics monitoring and faculties have freedom to do whatever they want.

I am interested in the work of Nick Wise. But there is no record of him before 2019. Any CV of him available about his BSc, MSc and PhD? How someone is hired by Cambridge for research and yet devote his time to ethics work only.

The Problematic Paper Screener where Nick contributes to, has no XAI model and is biased. Thus the sensitivity is on certain nationals. In addition is some cases Nick handles things out of Problematic Paper Screener and one might think he took it too personal. See a recent contribution of Nick to Pubpeer:

https://www.pubpeer.com/publications/5F1825A8F94E77E400A090294142C1

What he highlights is not a tortured phrase.

A tortured phrase finds its true meaning if and only if the article concept, data and method is not original and the tortured phrases are used systematically throughout the article for the purpose of hiding the duplication.

Picking on an original article that uses an alternative wordings damages the nature and true efforts of Problematic Paper Screener team.

Most, if not all, of the blames are on the publisher to permit special issues . His first misconduct of this kind resulting a retraction dated back in 2018. The question is why did he not learn his lesson and repeated this again and again? I do not really understand why the publishers never take responsibility. If just Elsevier handled peer-reviews of the special issues like MDPI most issues would have been resolved. Despite all criticism over MDPI model of publishing, this publisher manages the peer-reviews of special issues independent from the guest editors and all reviews and even final decisions are made by external scientists selected from the approved list of reviewer and editorial boards.

BTW, its extremely easy to spot tortured phrases. How about a little more challenging cases for Dr. Magazinov. Check out the Moritz U G Kraemer who in 3 years got H-index of 73 by being added in the studies with over 50 coauthors and other questionable articles. And the other issue is that G. M. worked with numerous co-authors who have no idea of such practices in special issues. Again, this is publisher to protect the coauthors. What is the fault of a student or a senior professor involved in the article? The fact is, receiving a few citations as a token for managing a SI might be a standard manner in the industry. But what G. M. can be taken responsible for would be his appearance in the special issues that he himself was involved in the peer-review.

If just Elsevier handled peer-reviews of the special issues like MDPI most issues would have been resolved. Despite all criticism over MDPI model of publishing, this publisher manages the peer-reviews of special issues independent from the guest editors and all reviews and even final decisions are made by external scientists selected from the approved list of reviewer and editorial boards.

BTW, its extremely easy to spot tortured phrases. How about a little more challenging cases for Dr. Alexander Magazinov. Check out the Moritz U G Kraemer who in 3 years got H-index of 73 by being added in the studies with over 50 coauthors and other questionable articles. And the other issue is that Gunasekaran Manogaran worked with numerous well-known scientists who are currently shocking to read about this. Receiving a few citations as a token for managing a SI might be a standard manner in the industry. But what Gunasekaran Manogaran can be taken responsible for would be his appearance in the special issues that he himself was involved in the peer-review.

His first misconduct of this kind resulting a retraction dated back in 2018. The question is why did he not learn his lesson and repeated this again and again?

Check out the Moritz U G Kraemer who in 4 years got H-index of 73 being added in the studies with over 50 coauthors. Why non-EU citizens are always attacked?

After 40 years of medical research and publication, I retired disillusioned by the unethical behavior of universities and major journals. During a meeting in London, a journal editor said tho me, smiling, “I’m glad that I published the last manuscript that you reviewed and rejected, because the bulk reprint order paid for my salary for a year.”. (The pharmaceutical company probably just tossed the boxes of reprints without even opening them.)

Interesting. Well done. I wonder if this affects meta-analyses, the so-called gold standard for definitive research, which I have always found suspect. Garbage in, garbage out.