In the Death of an Iranian Scientist, Hints of Unchecked Strife

The news of Zahra Jalilian’s death seemed to change as quickly as it spread.

On Dec. 4, 2022, the University of Tehran announced that the nanotechnology graduate student had died following “a tragic self-harm incident.” Political opposition groups quickly countered that darker forces were likely at work, attributing the 31-year-old Ph.D. student’s death to mercenaries, Iranian security forces, and other plots. Jalilian’s family, meanwhile, has accused her adviser of getting rid of his student in order to take credit for her work — charges that he steadfastly denies.

What is clear amid the varying and sometimes overheated accounts is that Jalilian was struggling under the pressures of her research. Interviews with her former colleagues, alongside a voice memo that appeared on a university messaging platform shortly after her death, provide a rare glimpse into the culture of a scientific lab in a country that is often opaque to the outside world — and where mental illness is often ignored, denied, and deeply freighted with stigma.

It’s “an environment that is very chaotic and very unsafe,” Saba Alaleh, a clinical psychologist who recently left Iran and now lives in Turkey, told Undark through an interpreter.

The precise details surrounding Jalilian’s death remain unclear and the university did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the status of the official investigation. But experts consulted by Undark said the problem of mental health care in Iran, or the lack of it, is particularly acute in academia, where Ph.D. students — most of whom are unpaid — toil under relentless pressure to publish groundbreaking research. Few socially accepted avenues exist for seeking help when those pressures begin to take too heavy a toll.

“Students are totally screwed in Iran,” wrote Cina Foroutan-Nejad, an Iranian-trained chemist living in Poland, in an email message to Undark. “That’s why everyone is trying to leave the country.”

Jalilian, who went by the nickname Mahsa, grew up in Kermanshah, a city in the Kurdish part of western Iran. It’s an area of the country where recent clashes between protesters and government forces have been particularly fierce. But Jalilian’s interests did not lean toward political activism. Hers was an appetite for learning, and she devoured books on anything from chemistry to religion to psychology, her brother, Amir Hosein Jalilian, told Undark.

Zahra Jalilian also loved nature. On outings to the oak-covered mountains surrounding their hometown, she would always bring a bag to collect litter from other hikers, Amir Hosein recalled. Sometimes she picked acorns from under the shade of the mother tree and planted them in sunnier spots, where they stood a better chance to thrive.

At Razi University in Kermanshah, not far from her family home, Jalilian studied nanophysics for her master’s degree. Her technical bent also showed on Twitter, where she posted images of nanomaterials that looked like abstract art. The one tweet she made that wasn’t about science shows pictures of Persian oaks.

“She wasn’t political,” said Maryam Shojaee, who began her Ph.D. program with Jalilian in 2017 at the University of Tehran. “I think she was even religious, because she was always wearing a perfect hijab.”

Shojaee had come to Tehran from the city of Shiraz, where she earned her master’s degree, and for a while, Jalilian was her only friend. They did their homework together and lived in the same dormitory complex in a leafy, high-class area of the city. But over time the friendship strained. According to Shojaee, Jalilian complained often about her roommates, fretted over her studies, and obsessed about grades. Shojaee said she felt her friend passed the anxiety on to her. Once they started doing research in the nanotechnology lab of Shams Mohajerzadeh, a prominent professor at the university, the two had already begun to drift apart.

At first Shojaee, who now works in England, blamed herself for failing to get along with Jalilian. But while Shojaee was busy teaming up with her new lab mates, Jalilian kept to herself. “I noticed that most of the time she was alone,” Shojaee said. “She didn’t work with other people.”

Mohammad Saghafi, then a master’s student who used some of the same facilities as Jalilian, confirms this impression. He saw Jalilian a few times, he told Undark, but they never spoke. Usually, people would start a machine running in the lab’s cleanroom, then have a cup of coffee or tea while they waited for it to finish. “So you make friends there with people. But she was not there, never,” he said, noting that Jalilian was quite isolated.

Zahra Jalilian, who went by the name Mahsa, died in December 2022. While the precise details surrounding her death remain unclear, multiple sources said that Jalilian was struggling under the pressures of her research.

Visual: Courtesy of Amir Hosein Jalilian

Saghafi knew what that felt like. Years earlier, as an undergraduate at the university, he had struggled with depression and anxiety. In the middle of a class of one or two hundred students, he could feel utterly alone, unable to make a single genuine human connection. That in turn led him to avoid socializing. “It’s like an ugly scar on my face, everybody can see it, so I should be hidden,” said Saghafi, who is now a Ph.D. student in the Netherlands. “Maybe it was the feeling for Zahra as well.”

Surveys show that, at least in the West, mental health among college students has been worsening for years, with counseling centers experiencing soaring demands for care. Comparable data from Iran do not seem to exist, but on global maps of mental illness in the general population, the country sticks out: In 2019, Iran had the highest prevalence of mental health disorders in the world.

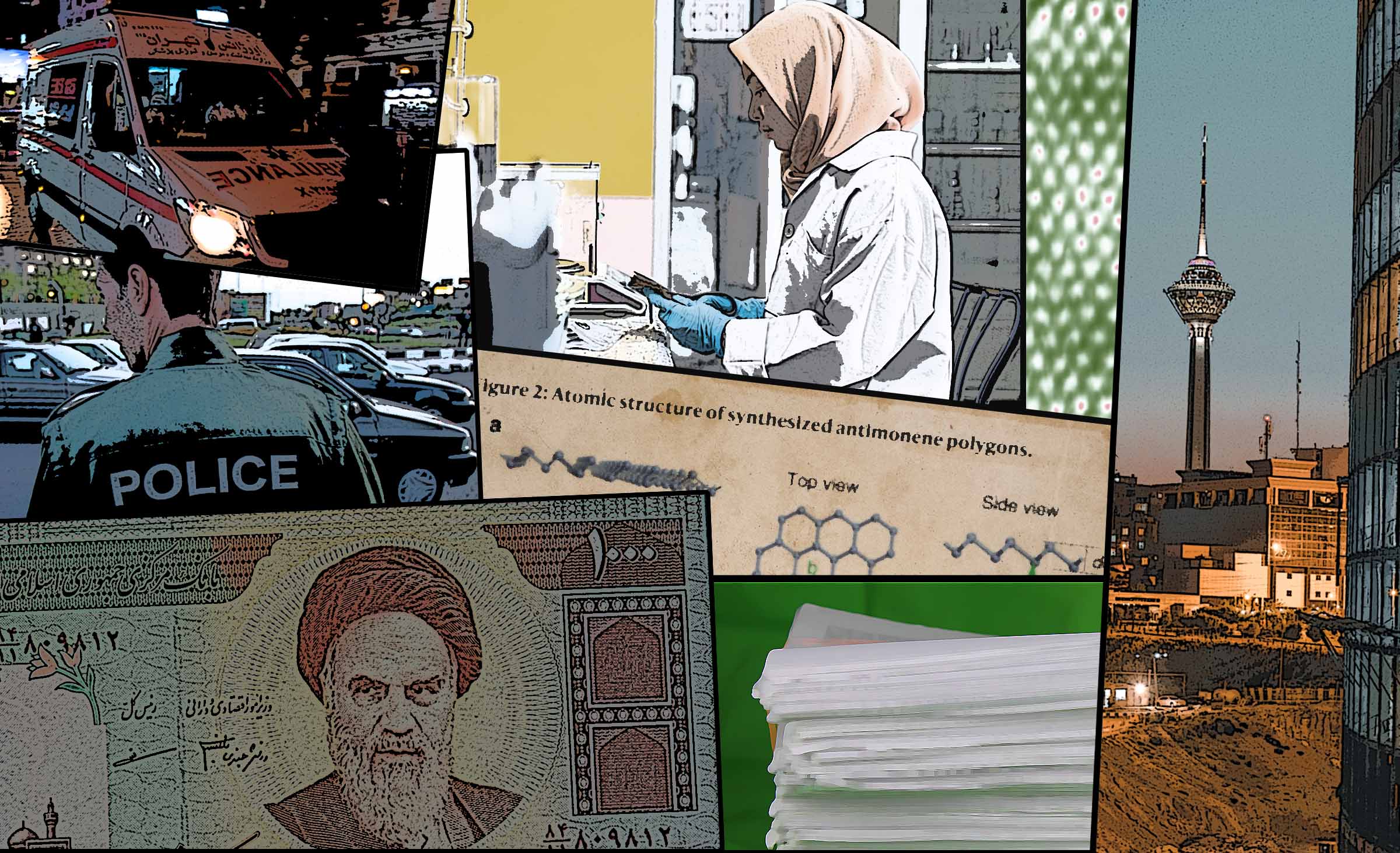

Toughened U.S.-led sanctions, the pandemic, a persistent drought, and economic mismanagement by the government have compounded the nation’s woes. In December 2021, Alireza Zali, head of Tehran’s Covid-19 task force and chancellor of one of Iran’s largest medical schools, said that a third of Iranians suffered from a mental disorder. Suicide, viewed as a sin in Islam, is reportedly on the rise.

“Clients report more anxiety, dysphoric mood, and unstable relationships than ever before,” Iman Najjar, a psychotherapist in private practice in Tehran who often treats university students, told Undark by email.

Despite the high number of people with mental illness, stigmatization is widespread in Iran. “There is no cultural understanding in our society; they ridicule us,” one person told researchers in a study published in 2013. “If my family realized that I am sick they would abandon me because they think it is in the genes.” In a 2017 study in the Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, a man referred to as a “recovered patient” said: “My family hides my disorder from neighbors, our relatives, and acquaintances. However, always there is a question that why I am not working or why I am not getting married?”

Najjar, the psychotherapist, said that although universities have psychological centers, they “do not interact enough with teachers and professors of the university.” And because “the teacher-student relationship is a top-down relationship,” he added, students mostly cope with conflicts through “avoidance.”

Over time, Jalilian’s social struggles grew more apparent. A woman who describes herself as her “dormitory friend” told Undark by email that Jalilian felt “neglected” and “punished” by her lab mates. “For example, she said that she was not invited to parties and birthdays,” said the woman, who requested not to be identified for fear of reprisals.

Jalilian clashed with other members of her lab. In those arguments, she “used to say that ‘I will hurt myself or I will do something to myself or you will regret it,’” Shojaee said. (Undark contacted two other lab members who overlapped with Jalilian, but they did not respond to interview requests.)

“In our lab we have a lot of chemicals, we have a lot of machines,” Shojaee added, suggesting that Jalilian’s threats of harm raised particular concern among her colleagues: “I remember one time my professor told me, ‘I avoid any argument with her anymore because she has said such a thing and I’m afraid she’d do something to herself or to you guys.’”

After one particularly fierce altercation last year, some of Jalilian’s lab mates went to talk to a university therapist about her threats. But according to the dormitory friend, Jalilian lost trust in the counselor who, allegedly, didn’t treat her concerns confidentially. (The counseling center and university officials didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.)

The fickle nature of the experimental work Jalilian was doing, which involved manufacturing new nanomaterials, also may have taken a toll on her mental health.

“You start a project, but you have no clue if it’s going to work, if you can produce such a thing or it’s just an idea,” Shojaee said. “So, it’s like you’re wasting a lot of time, you have the pressure of publication and everything. And I think for Mahsa, it didn’t work well.”

Research shows that academic pressure is a strong predictor of poor mental health among college students. And in Iran, the strain is immense, several people told Undark. For Saghafi, who ranked 160 out of hundreds of thousands at the national university entrance exam, the unrelenting demands only deepened his misery. His grades plummeted, and he saw a counselor at the university. It didn’t help. The school eventually kicked him out and he had to finish his bachelor’s elsewhere. “It’s not a life, it’s really difficult,” he told Undark. By comparison, becoming a Ph.D. student in Europe felt “like retirement.”

Jalilian also showed signs of buckling, according to Shojaee. Although the two were no longer close, they would talk over tea from time to time.

“She was like, no, it’s not going well, I don’t have any good results, I can’t have a publication yet and the machine is not working properly,” Shojaee recalled. “And she was always stressed, she was always worried about the equipment, and she was like, ‘I’m so worried about my Ph.D.’”

Amir Hosein disputed this characterization of his sister, emphasizing she had never been to a psychiatrist and was not taking any pills.

“Zahra never hurt anyone, including herself,” he added, “because in the religion of Islam, this is a great sin.”

Amir Hosein says he filed a complaint with authorities accusing his sister’s adviser, Shams Mohajerzadeh, of being responsible for her death. While an investigation ensued, no known action has been taken against Mohajerzadeh, who told Undark that in the days before Jalilian’s death, he and Jalilian were on the cusp of a triumph.

Late into the evening of November 30, 2022, he said in a Farsi voice memo that was shared on a university group channel on the secure messaging platform Telegram, the pair were making the final tweaks to a manuscript that summed up all her efforts in the lab, which was subsequently submitted to the respected journal Nature Communications. After years of toiling and fretting, he and Jalilian finally had something to show for it. “As a researcher, this was the best work of my life,” Mohajerzadeh recalled days later in the voice memo.

That called for celebration. “I was so happy that I went to buy a cake, and she was so happy that she told me that ‘these are the best days of my life,’” Mohajerzadeh said.

The news had also reached Shojaee in England. “I was so happy for her,” she said. “Everything seemed to be perfect after many years, after a lot of arguments, after a lot of challenges, everything seemed to be fine.”

According to the manuscript, which Undark has seen, Jalilian had invented a new device allowing her to grow atom-thin sheets of antimony, a brittle and toxic semi-metal with a history that stretches back to antiquity. When its two-dimensional form, called antimonene, was first isolated in 2016, it triggered an avalanche of research.

For now, researchers are still sorting out how to best create the material. “Antimony in 2D is very difficult to achieve,” said Gonzalo Abellán, who heads the Two-Dimensional Materials Chemistry Lab at the University of Valencia in Spain. While the material is still not commercial, to his knowledge, he told Undark it is “very promising” in several areas, including medicine (it may boost the effect of cancer radiotherapy), energy storage (it might improve sodium-ion batteries) and IT (it could slim down computer chips).

In their initial comments on the manuscript, the journal’s reviewers also seemed positive, highlighting the “novelty” of Jalilian’s method and the topic’s “great promise.”

If she had found a commercially viable way to produce antimonene, or even just advanced the field a little, it could be a consequential discovery. To her family, it also seemed a plausible motive for a heinous crime. While offering no evidence, Amir Hosein suggested to Undark that Mohajerzadeh, a prolific scientist who holds numerous patents, had “tried to secretly register the invention in his name.”

In a brief email exchange in January, Mohajerzadeh, who had taken a leave from work, told Undark that Jalilian’s death had hit him hard. “I am so shocked with this mishap that I can’t talk about it. Zahra was one of my best students over my entire educational life as a professor and this thing is not at all acceptable for me.”

In the voice memo posted to the group Telegram channel, however, he laid out his own version of what happened. In addition to the experimental work by Jalilian, which formed the backbone of the manuscript, a master’s student in the lab had helped with simulations and had been added as the second author. At some point following the celebration in the lab, Mohajerzadeh said, Jalilian and that master’s student, Hesam Adib, had an argument. What exactly drove the disagreement is unclear from the memo, but Mohajerzadeh suggested a meeting with all three of them and Jalilian agreed.

On Dec. 3, however, she came to see Mohajerzadeh again. She was anxious, he said, and wanted her name removed from the manuscript. “I said it is your project. This is a shame,” Mohajerzadeh said in the voice memo.

According to Mohajerzadeh’s account, the argument escalated until Jalilian declared the article would be published without her. Her adviser described himself baffled, asking her “What do you mean?”

Zahra Jalilian’s grave.

Visual: Courtesy of Amir Hosein Jalilian

In the hallway of the building they were in, a staircase led one flight down. According to Mohajerzadeh, Jalilian stormed out of the room and into the hallway where she threw herself off the stairs and into the wellhole.

Shojaee recalls being on the phone with a friend from the lab when suddenly the friend told her she had to go “because Mahsa threw herself.” Later that day, Shojaee heard from the same friend that Jalilian had been taken to the hospital and undergone surgery. She died there the following morning.

As the shock began to recede, Shojaee felt a nagging sense of regret. She wondered how, despite all the warning signs, her former friend and lab mate could have still slipped through the cracks. “If somebody needs help and everybody knows it and everybody sees that this is not normal, and if somebody says that ‘I will do something to myself,’ maybe we should — everybody, all the lab mates, the professor, the therapist, everybody — maybe we should take it much more seriously,” she said.

Helia Ghanean, an Iranian psychiatrist who now lives in Canada, pointed to the lack of training in conflict resolution and teamwork in Iran’s educational system. This could make the skewed power relationship between student and professor particularly tricky to navigate, she told Undark. “How do you expect someone to solve a problem in a very positive way when everything around is negative?” Ghanean said. “I feel sorry for both the professor and the student. Because I believe they’re both in the same broken boat.”

In February, Mohajerzadeh said, he paid a secret visit to his former student’s grave, several hundred miles from Tehran, to “be with her for some time and recite Quran for her.”

Meanwhile, Jalilian’s family continues to insist that in the days before her death, the young researcher had expressed concern that her adviser was vying to patent her work under his name.

Iran does not make patent applications publicly available, but when contacted by Undark in March to ask about the accusations against him, Mohajerzadeh wrote back within two hours. He confirmed the content of the voice memo posted to the university’s Telegram channel immediately after the incident on Dec. 3, and he explained that, indeed, Jalilian had also been concerned about various patent issues.

But in his own defense, Mohajerzadeh also shared what he described as a screenshot of the application he made for a patent on the antimony research that he and Jalilian had spearheaded. It appeared to have been filed on Feb. 28, 2023, and it included both Jalilian’s and Mohajerzadeh’s full names.

Next to each name, a number indicated each applicant’s share in the patent: 50 percent.

Frederik Joelving is a journalist focusing on health, science, and investigative reporting. He works as an editor for Retraction Watch.

This story was produced in collaboration with

This story was produced in collaboration with

This is a very poignant discussion and commentary, but readers should in no way imagine that it is specific to one country or research culture. PhD students around the world are prone to rates of diagnosable moderate-to-severe anxiety and depression, as well as a rate of potential suicide that is 10-times greater than seen in the general population. Articles like this bring attention to specific cases, but if we are to address the issue in any meaningful way, then the national bodies that profess to care for students (and who act in the name of mental health in general) need to have urgent and collaborative discussions, and take concrete action to ensure that the potential for harm is at least reduced to the minimum level possible. Without such actions, the policies and words of universities and overarching bodies are hollow. If people would like data and figures on this topic, then please get in touch.

Making a statement about a country in which you have no personal experience seems easy. When you discuss a mental health system that can help students, it is important to ask yourself, who opposes such systems and who determines the priorities? Yes. It is the government and its militia that are responsible for this. There were those who shot down a flight and denied it for several weeks. This is a system which does not take its citizens’ lives into consideration. You are referring to Iran, a country where everything is literally political. It is unlikely that you know the Iranian Islamic bureaucratic system. There are many suicides that could have been prevented if these individuals (such as Zahra) had been aware of a way to resolve their concerns. A human being who has access to the internet has the opportunity to communicate with authorities from anywhere in the world. Your patent or other publications can be brought before the organizations that make you concerned. At the very least, you will be able to get a hearing from them. Iran does not have such a system in any form. Here’s the surprise! Iranian citizens are restricted from internet access. Isn’t it interesting to see who is doing it? Those you expect “to care for students and have urgent and collaborative discussions”. Can you really count on this system to make a difference? Could we perhaps stop generalizing and think about the unique situation in a country whose social conflict occurs beneath its skin?