Since OpenAI unveiled ChatGPT to the world last November, people have wasted little time finding imaginative uses for the eerily human-like chatbot. They have used it to generate code, create Dungeons & Dragons adventures, and converse on a seemingly infinite array of topics. Now some in Silicon Valley are speculating that the masses might come to adopt the ChatGPT-style bots as an alternative to traditional internet searches.

Microsoft, which made an early $1 billion investment in OpenAI, plans to release an implementation of its Bing search engine that incorporates ChatGPT before the end of March. According to a recent New York Times article, Google has declared “code red” over fears ChatGPT could pose a significant threat to its $149-billion-dollar-a-year search business. Could ChatGPT really be on the verge of disrupting the global search engine industry?

It’s doubtful. ChatGPT is good at what it does — generating what appears to be knowledge in a conversational manner — but a search engine it is not. It responds to prompts like you might expect a really smart person to, even if it can’t directly answer your questions.

It makes some sense that Google might see chat, were it to be widely adopted as a search tool, as a threat to its business model. It’s much easier to incorporate advertisements into listed search results than into chatbot responses. If fewer people are doing conventional search, that could potentially have a serious effect on Google’s bottom line. But the real question here is: Can ChatGPT even be used to do Google-like searches?

To understand the answer, let’s compare the two technologies.

Google and similar search engines are essentially superhuman librarians. They can find any internet site you want and recommend other potentially related sites, typically in just a fraction of a second. Then it’s up to you to decide whether or not those sites are good sources for what you’re trying to accomplish.

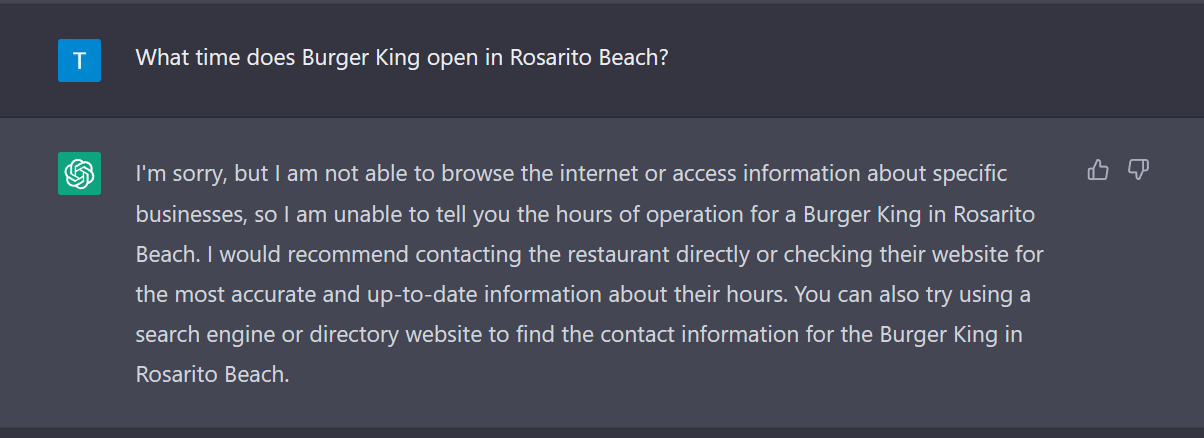

ChatGPT, on the other hand, is less like a librarian than like a psychic who claims to commune with the dead. Its most glaring flaw as an internet search tool is that it can’t connect to the internet — at least, not to the internet post-2021.

That renders ChatGPT useless for answering most search queries. The most searched terms on Google are consistently those related to breaking news and to local or personal information such as places to eat, banking info, and stock market websites — queries that require accurate, up-to-date information.

Even if chatbots could trawl the internet in real time — a feat that technology experts have not yet figured out how to achieve — they would likely prove to be poor go-betweens for internet searches.

That’s because models such as ChatGPT are trained to “hallucinate” text. They don’t search their databases for relevant passages and regurgitate or reword them. Rather, they use a process much like the autocomplete function on your phone to build responses one word at a time.

These models don’t understand what they’re outputting any more than an ink pen does. If you ask ChatGPT the same query during five different sessions, you may get five different answers, possibly contradicting one another. Adding the ability for the chatbot to access the internet in real time won’t make these “hallucinations” any more accurate or reliable.

Add to that list of shortcomings the fact that chatbot language generation is incredibly slow, compared to search engines. For example, when I Google searched “explain string theory,” the query returned 55.7 million results curated by relevance in less than a second. The same prompt, when I gave it to ChatGPT, took anywhere from about 15 to 90 seconds to resolve depending on how verbose the model chose to be at a given moment.

Even if the chatbots could respond more quickly, their paragraph-format responses aren’t exactly ideal for readers who want to process a lot of information quickly. Once the novelty of chatting with a robot wears off, most humans will likely go back to wanting their information delivered fast and in easy-to-parse lists.

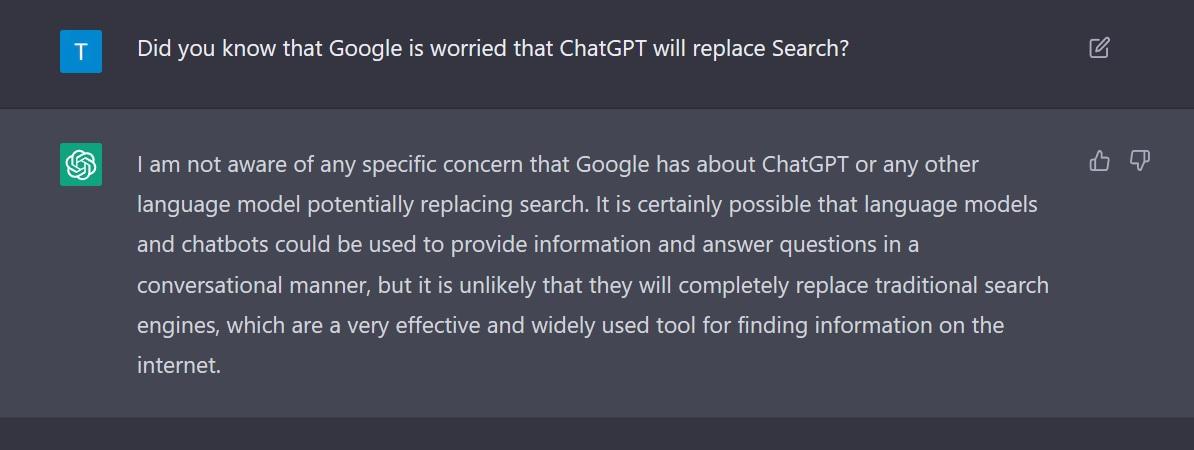

You don’t have to take my word for all of this. Even ChatGPT itself doesn’t seem to think it poses much threat to Google:

So why all the fuss in Silicon Valley about ChatGPT and search?

Most likely, it seems, ChatGPT-style bots will be paired with existing search engines to offer a user interface that serves both traditional search engine queries and chatbot prompts. That’s the model that was adopted by You.com, a boutique search engine that launched its own GPT-like chatbot in December. Rather than replacing the traditional You.com search experience, the new “YouChat” feature merely appears as a link beneath the search bar. The innovation here is putting two very different AI-powered apps on the same page. It’s probably safe to assume that Microsoft will do something similar when it integrates ChatGPT into Bing this spring.

That being said, there’s something fun and exciting about communicating with a robot that passes our personal Turing Tests. And some folks, when asking the kinds of questions that chat is good at answering, might prefer the conversational, colloquial touch of chat to the cold utilitarianism of listed results — even if it comes at the expense of accuracy. ChatGPT is a lot of fun to play with and, with further development, it may even have a bright future as a digital assistant.

But that doesn’t mean chatbots will revolutionize the world’s most popular search engine, much less replace it. For now, they are too slow and too stupid to be useful for much more than entertainment purposes. Saying that ChatGPT is a threat to Google’s search engine is like saying podcasts will replace universities. There’s certainly some user overlap, but the technologies serve entirely different purposes.

Tristan Greene is a freelance futurist, U.S. Navy veteran, and technology journalist covering artificial intelligence and quantum computing.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

ChatGPT is so negative tool and students can use it to cheat.