If the U.S. Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade in the coming weeks, as a leaked draft of the majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization suggests it will, the decision will thrust the country into legal terrain that has largely remained uncharted for the past half century. As many as 32 states are likely to ban or severely restrict abortions. But the laws won’t change the fact that many residents in those states will still want or need abortions. Absent the long-held constitutional right to exercise control over their own bodies, to what lengths will people go to secure access to reproductive care, and who will help them?

To get a sense of what the post-Roe era might look like, one place we can look to is Myanmar. I have been reporting on the country since a coup overthrew the nation’s government last year, and I have spoken to activists and anti-coup rebels about the role reproductive rights play in the struggle for democracy there.

In Myanmar, abortion is illegal unless the pregnancy can be proven to be a risk to the life of the birth parent. The laws governing abortion have not changed since they were first enacted in the 19th century, when Myanmar (also known as Burma) was under British colonial rule. In 2013, the country began developing a new law in order to meet international norms on gender and sexual-based violence, providing activists with some hope that the country might update its outdated laws on abortion.

Yet according to advocates, who pushed for better protection of reproductive rights, the bill fell short of meeting those standards. And after eight years in limbo, deliberation on the bill was derailed by a 2021 military coup that precipitated the collapse of the nation’s health care system. Certainly, if the post-coup conflict is anything to go by, the international standards the law was initially intended to address have been ignored completely by the military junta, which routinely uses rape as a weapon of war and form of punishment. Seen in this context, a ban on abortion is just another form of violence used by a repressive state.

The threat of significant jail time for people in Myanmar who have an abortion has given rise to a network of black market abortion pills and providers. Some of the resulting underground abortions are dangerous, and because of the looming threat of strict sentences, people who undergo them likely choose not to seek post-abortion care, exposing themselves to potential long-term medical and psychological consequences. According to the United Nations Population Fund – Myanmar, complications arising from unsafe abortions are a leading cause of death for pregnant people in Myanmar.

Since the 2021 coup, a new generation of young people have risen up in protest, and they are attempting to do away with many of the ethnic and gender divisions that previously served as barriers to intersectional solidarity in the country. In order to counter a status quo that perpetuates sexism in legal and cultural codes, some activists and grassroots organizations are using organizing methods inspired by a concept known as mutual aid.

The practice of mutual aid is an old one, first conceptualized as an organizing theory by Russian anarchist Pëtr Kropotkin in 1902. Mutual aid, unlike charity, seeks to give help without reinforcing hierarchy; it is often described using the phrase “solidarity, not charity.” Mutual aid groups are generally collectives of people giving what they can and getting what they need. The reciprocity in mutual aid need not be direct; the goal is to create a system in which needs are fulfilled for everyone, not just those with resources.

Mutual aid groups have often sprung up around the world to address disasters, like Hurricane Katrina and the Covid-19 pandemic. They are commonly used to provide health care in parts of the world where access to care is limited by rules or resources. In neighboring Thailand, thousands of people receive free medical care from the Mae Tao Clinic, established by doctor and pro-democracy activist Cynthia Maung.

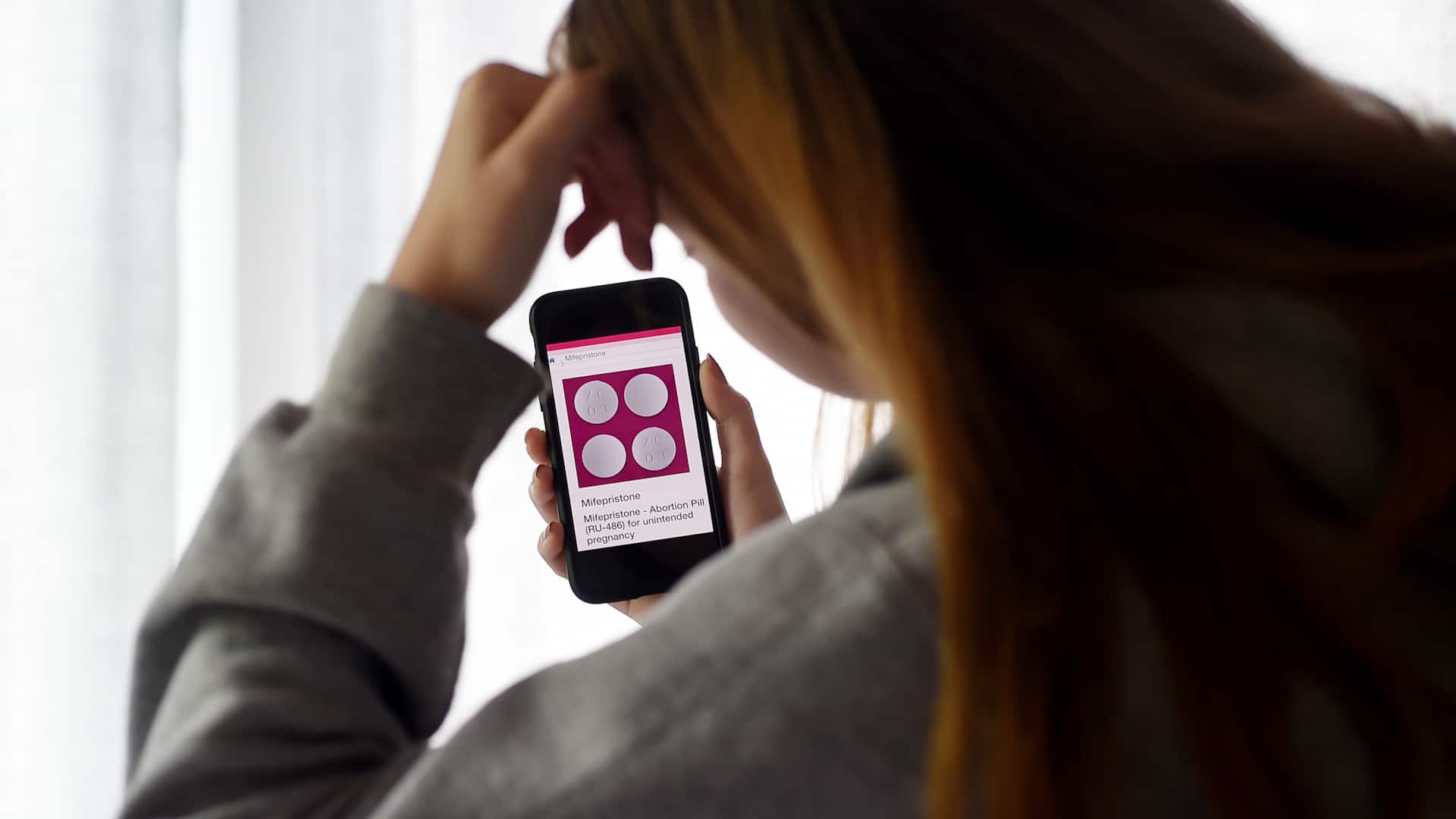

Although the group doesn’t explicitly describe itself as a mutual aid group, it functions much like one. Medics provide reproductive care and even birth certificates to people, allowing children of migrants to access Thai public services. Meanwhile, a separate team associated with the clinic sends backpack medics to remote villages and other underserved areas. Other groups provide care in cities and areas where government control is stronger, and they have supported black markets for drugs like misoprostol, an over-the-counter treatment for ulcers that is commonly prescribed in the U.S., off-label, to induce abortions, in combination with another drug, mifepristone.

Now that the Supreme Court seems poised to overturn Roe v. Wade, mutual aid groups and other grassroots networks that follow a similar model may become more popular stateside.

Such networks existed before Roe. Between 1965 and 1972, an underground group known as the Jane Collective facilitated some 11,000 abortions in the Chicago area. Whereas the women of the Jane Collective performed abortions themselves — which they openly acknowledged involved risk — today, a new wave of underground networks aims to facilitate reproductive care by sharing knowledge. One group, the Four Thieves Vinegar Collective, recently published a recipe for a homemade medical abortion pill online. Like the Jane Collective’s underground procedures, these do-it-yourself abortion pills can carry serious risks. They could have dangerous interactions with other medications or conditions, and they are by no means a viable substitute for safe, legal abortions. But for people who feel like they have no other options, the groups provide one — and the kind of knowledge they are disseminating can’t be stopped at borders or legislated out of existence. The days of powerful people having a monopoly on information are gone.

Ideally, everyone, everywhere would have access to safe, legal, and affordable abortions. But the last few years have repeatedly shown us that merely voting is insufficient to protect marginalized people from state violence and control. Hopefully, states that enshrine the right to reproductive autonomy in law will also consider protecting and giving sanctuary to people who help facilitate abortions in states where those rights have been rescinded.

During the pandemic, people across the country supported their communities when the unequal power structures of government failed them. Although facilitating safe abortion is more complicated and riskier than going shopping for elderly neighbors, the same principles apply. Throughout history and across the globe, from Myanmar to the U.S., people marginalized by a callous system have found ways to step up to protect each other. And in a post-Roe world, they will continue to do so.

James Stout is a historian of anti-fascism and a freelance journalist. He has covered the Spring Revolution in Myanmar for the iHeartRadio podcast “It Could Happen Here.”