Six months after Pfizer and BioNTech began large trials of their Covid-19 vaccine in young children, the companies announced Monday that the shot had a “favorable safety profile” and provoked a strong immune response in kids aged 5 to 11.

The companies are yet to publish the full data. And although the reported antibody response suggests that the vaccine does protect against illness, the results of the trial — involving 2,268 participants — couldn’t provide direct evidence that the vaccine lowered incidence of Covid-19, because too few subjects got sick. “It’s not a lot to go on, but what we do have to go on looks great,” Kathleen Neuzil, who directs the University of Maryland’s Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, told STAT.

The announcement raised hopes that the Food and Drug Administration will soon authorize the vaccine for kids aged 5 to 11, allowing them to join the roughly 280 million Americans 12 and up who have access to safe, highly effective Covid-19 vaccines. (Already, some parents are reportedly lying about their kids’ ages in order to get them shots.) If the time between the arrival of trial data and FDA authorization is similar to earlier trials, science journalist Apoorva Mandavilli wrote in The New York Times this week, “millions of elementary school students could begin to receive shots around Halloween.”

For months, experts have debated whether it makes sense to vaccinate young children against Covid-19, especially amid ongoing vaccine shortages in many poor countries. At issue is a delicate risk analysis. Authorized Covid-19 vaccines are overwhelmingly safe and effective, but they can have side effects. Meanwhile, severe complications from Covid-19 remain very rare in children. As Sara Talpos reported for Undark in April, for some experts, that risk-benefit calculus could suggest that widespread Covid-19 vaccination for healthy kids may not be warranted.

In the United Kingdom, such considerations have pushed regulators to move more slowly to vaccinate children 15 and younger. In early September, a British expert advisory panel concluded that, while “the benefits from vaccination are marginally greater than the potential known harms,” there was not yet sufficient evidence to merit offering Covid-19 vaccines to healthy 12 to 15 year-olds.

The British government has since opted to recommend a single dose to kids in that age bracket, in part because of the challenges posed by the highly infectious delta variant. And many experts remain convinced that childhood vaccination is vital to blunt the spread of a devastating virus — and to head off the rare events in which children do experience complications from Covid-19.

While Covid-19 vaccines for kids are making headlines, the bigger issue, perhaps, remains the global drop in routine childhood vaccination for diseases like measles and diphtheria. Even in the United States, pandemic-related disruptions in care have left many kids behind on those immunizations. “Frankly, a lot of the diseases that we vaccinate kids for are more severe in children than Covid,” pediatric infectious disease expert Sean O’Leary told NPR last month. “And so the last thing we want as we reenter the school year is outbreaks of these other vaccine-preventable diseases.”

Also in the News:

• The delta variant of the SARS-CoV2 virus continues to drive the Covid-19 pandemic, health officials say, with the World Health Organization reporting this week that delta has outcompeted other variants around the world. By last month, delta accounted for more than 90 percent of all new Covid-19 infections in the U.S. Still, some scientists have expressed cautious optimism that the worst of the U.S. delta wave has arrived, and that the winter months ahead may be far less deadly. A combination of vaccination and immunity acquired via Covid-19 infection could blunt the virus’ impact, and some pandemic models project a steady decrease in cases through March of next year. Other experts expect a winter bump in infections. “It is likely we’ll see some wave,” Trevor Bedford, a computational biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, told STAT, adding that he hopes it will be considerably lower than last winter’s surge. If that sounds cautious, it is. Infectious disease experts stressed the uncertainty of dealing with a relatively new pathogen, as well as the possible projection-scrambling effects of a new variant. But some experts say there are definitely glimmers of hope. “I think these projections show us there is a light at the end of the tunnel,” University of North Carolina epidemiologist Justin Lessler told NPR. (Multiple Sources)

• On Monday, the Biden administration announced that it would create new federal policies to help protect workers from an increasingly common hazard: extreme heat. Such heat — characterized as summertime weather that is much hotter, more humid, or both compared to average conditions — is a leading cause of weather-related death in the U.S. In the summer of 2021 alone, extreme heat waves in the Pacific Northwest killed hundreds of people. And as BuzzFeed News pointed out this week, experts say those particular heat waves “would have been ‘virtually impossible’ without climate change.” Previously, there were no federal rules specifically governing heat exposure, and workers toiling outside — such as farmworkers and construction workers — have been particularly vulnerable; an estimated 384 have died from extreme heat over the past decade. New standards may help reduce that toll, proponents say. According to the White House announcement, the Department of Labor is “launching a multi-prong initiative on occupational heat exposure to protect outdoor workers,” and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration will develop new heat-related rules and oversight. In addition, government agencies will help increase cooling centers, add tree cover to urban areas, and take other steps to help people weather extreme heat. (BuzzFeed News)

• This week, the Australian Research Council (ARC), a major research funder in Australia, reversed its decision to reject grant applicants for citing preprints — papers that are yet to be peer reviewed. The policy had outraged many Australian researchers, who called it out of step with modern publishing practices. Some early-career researchers told Nature that, because of the policy, their grant applications had been rejected, which had “effectively ended their careers” because there are limits in how many times they can apply. The decision comes after an anonymous researcher posted on Twitter dozens of applications that were rejected for citing preprints. The policy reversal will, however, not apply to researchers whose applications are currently under consideration or were previously rejected for citing preprints. Rejected applicants will have the option to appeal, but one researcher told Nature that the process “places more pressure on researchers” who are already stressed by the pandemic, which has thinned the job market in Australia’s university sector. When asked why the ARC will not reconsider rejected applications, a spokesperson told Nature, “Rules cannot be changed following the closing of a scheme, nor can they be disregarded during the assessment of the scheme.” (Nature)

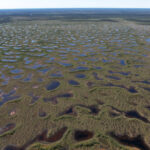

• With the summer melting season drawing to a close, Arctic sea ice cover has now reached its lowest extent of the year, scientists at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) reported this week. Thanks to a relatively cold and stormy summer in the region, the ice’s retreat was mild compared with recent years, said NSIDC director Mark Serreze. At this year’s minimum — most likely reached on Sept. 16 — the Arctic retained about 1.82 million square miles of sea ice cover, 25 percent more than at last year’s low point. Still, climate change continues to push the long-term trend downward. This year’s sea ice minimum is still the 12th lowest in the satellite record, which stretches back nearly 43 years, and it is equivalent to roughly three-fourths the average minimum ice cover between 1981 and 2010. All 15 of the lowest sea ice minimums on record have occurred in the past 15 years. Moreover, scientists note that area is only one measure of sea ice health; also important are the ice’s thickness and age. And, Serreze said in a press release, “the amount of old, thick sea ice is as low as it has ever been in our satellite record.” (The New York Times)

• And finally: Earlier this week, the United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres and U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson hosted a closed-door meeting of world leaders and emissaries at the U.N.’s headquarters in New York City to discuss strategies for addressing climate change. The meeting was attended by 21 heads of state, though the leaders of the world’s top carbon polluters — Russia, India, China, and the U.S. — were absent, opting to instead send political representatives. Attendees from countries most vulnerable to climate change, such as the Maldives and the Marshall Islands, pleaded for greater action, according to Johnson. After one U.N. session, Costa Rican President Carlos Quesada complained abut the lack of progress. “If countries were private entities, all leaders would be fired, as we are not on track,” he said. “It is absurd.” The following day, in an address to the U.N., President Biden said climate change was among the “greatest challenges of our time” and pledged to double funding that helps poorer nations develop cleaner energy and adapt to the effects of climate change. (AP News)

“Also in the News” items are compiled and written by Undark staff. Deborah Blum, Brooke Borel, Lucas Haugen, Sudhi Oberoi, and Ashley Smart contributed to this roundup.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

So Pfizer and Biontech said their “clinical trials” had a ‘favorable safety profile” for young children? That sounds like a PR blurb. It also sounds sickening. Regulatory oversight needs to happen before clinical trials are even thought about. Childrens’ health and lives are at stake, so clinical trials aren’t synonymous with money-making schemes.