Imagine being a world-class scientist whose work was immortalized in James Cameron’s movie “Avatar,” and who inspired a character in Richard Powers’ Pulitzer-winning novel “The Overstory.” Others have written about her research, including Peter Wohlleben in “The Hidden Life of Trees.” Now, we finally hear from the scientist herself, Suzanne Simard, in “Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest.”

Her book comes at a time when governments in Western Canada in particular are being confronted over their continued approval of old-growth forest logging. It is a vital look at the importance of how we harvest and reforest wooded landscapes, and the misconceptions that have plagued the forest industry since the 1980s.

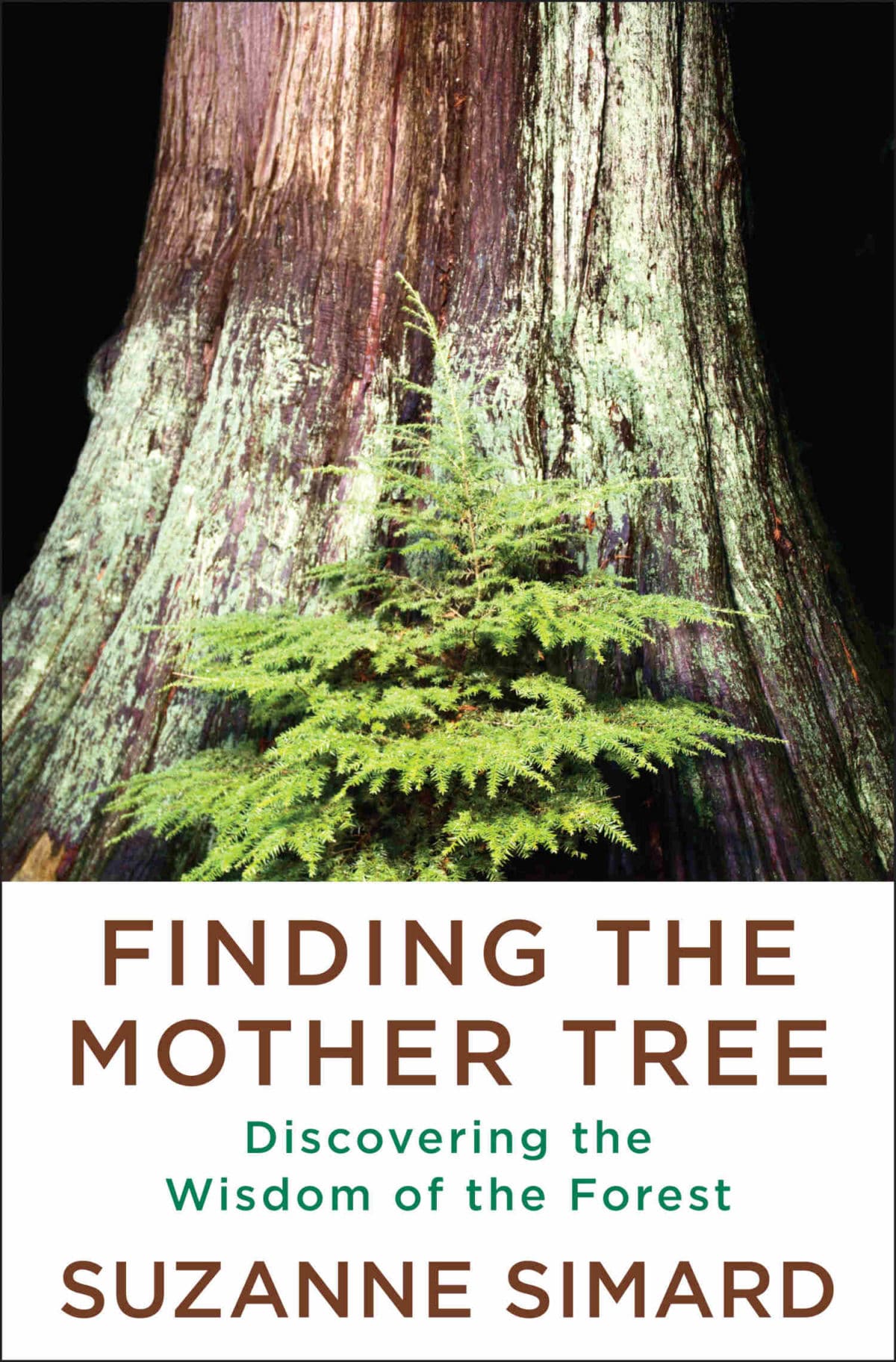

BOOK REVIEW — “Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest,” by Suzanne Simard (Knopf, 368 pages).

The book starts at the beginning of that decade, with Simard checking logged patches of forest (clear-cuts) for a logging company to see if they’d been properly replanted. She is no stranger to forestry, as her family were loggers in south-central British Columbia back when logging was done by hand with a crosscut saw and a horse to drag the logs out of the forest. But the forest industry she now works for is completely different than it was in those early days.

She finds that the company’s seedlings, placed in regulation holes at a set depth, failed to root and are dying instead. “There was an utter, maddening disconnect between the roots and the soil,” she writes. By looking at the roots of seedlings that are regenerating naturally, she gets an inkling that trees need to connect to the fungal (also called mycorrhizal) network in the soil if they are to thrive — without it, they don’t have access to vital nutrients.

The book outlines her quest to learn more about this network, a question around which she shaped her entire career, from working with the forest service studying forest growth, to becoming a university professor in her early 40s. Her research is focused on understanding the underground connections between trees of various species, and how instead of competing, they are actually interdependent and cooperate with one another. Competition is the foundation of evolutionary theory and natural selection, and “the prevailing wisdom was that trees only compete with one another to survive,” she writes. So finding that trees cooperate could present an evolutionary paradox.

As a government scientist, Simard helped foresters understand how to best manage forests. Her early work focused on the government policy of “free-to-grow,” which required contractors to dose harvested forest blocks with herbicide so there wouldn’t be any shrubs or trees, like alder and birch, competing with replanted seedlings for water, light, or nutrients. Beginning in the late 1980s, she set out to prove that the policy was misguided with a series of well-designed experiments that examined the role of alder and birch in the regrowth of planted seedlings.

Her findings were compelling, showing that alder contribute nitrogen to growing fir seedlings, while cutting birch trees made fir seedlings more susceptible to root disease. She used her data to model tree growth over a hundred years, finding that free-to-grow plantations produce a lower volume of timber of poorer quality than plantations not weeded or treated with herbicide. But government decision-makers didn’t consider her work long-term or representative enough. The free-to-grow policy wasn’t revamped until 2000, almost 10 years after she presented results from the first five years of her experiments.

Support Undark MagazineUndark is a non-profit, editorially independent magazine covering the complicated and often fractious intersection of science and society. If you would like to help support our journalism, please consider making a tax-deductible donation. All proceeds go directly to Undark’s editorial fund. |

Throughout the book, Simard struggles to have her voice heard by policymakers, though she feels she has to speak up in an attempt to change logging and replanting practices in a way that maintains forest diversity. Part of the problem initially was that she was a woman in a man’s world, but her findings also went against commonly held conceptions in the forest industry. Some researchers didn’t take her scientific results seriously, even though they were published in peer-reviewed journals like Nature, which coined the term “wood wide web” in 1997 in reference to her research. In fact, when she advised Nature to not publish a critique of her paper, saying its premises were easily dismissed, she set her work up for criticism by unwittingly stepping into the middle of a feud between researchers over the role of symbiosis in the evolution of trees.

Simard describes her experiments in detail, making it possible for the reader to understand what she is doing, why, and how. Her most groundbreaking experiment was one in which she injected different carbon dioxide gases into the air around a birch and a fir seedling, then measured whether the carbon traveled between the trees. Her results showed that birch and fir communicate: It was “like intercepting a covert conversation over the airwaves that could change the course of history,” she writes.

This communication happens through a network of dozens of fungi that connect the roots of the trees, and it’s a finding that Simard makes again and again in her experiments. Simard writes that our recognition that forests have “elements of intelligence helps us leave behind old notions that they are inert, simple, linear, and predictable.” Her findings are in step with the ideas of First Nations groups. She shares a story from Bruce “Subiyay” Miller of the Skokomish tribe, who said that, under the forest floor, “there is an intricate and vast system of roots and fungi that keeps the forest strong.”

While Simard can’t hide her excitement about her experiments, she also tells stories that show she’s only human: like the time she and her sister forgot to put filters in their gas masks while spraying herbicide, or the time she breathed in radioactive dust particles from her tree root samples while preparing them for analysis. She also weaves in stories about her personal life, including her relationship with her siblings, her marriage, and its dissolution, and her struggle with breast cancer. As she writes, “Our own roots and systems interlace and tangle, grow into and away from one another and back again in a million subtle moments.”

As an academic scientist, Simard was able to move from applied to more experimental research, though she continues to quantify subterranean connections between various tree species. She is currently focused on two projects: The Mother Tree and The Salmon Forest. The former is a study of the oldest conifers in nine forest stands and how they interact with seedlings around them, especially whether they’re kin or stranger seedlings. She notes that “The forest seemed like a system of centers and satellites, where the old trees were the biggest communication hubs and the smaller ones the less-busy nodes, with messages transmitting back and forth through the fungal links.” She likens it to a neural network, with information “transmitted across synapses.” Researchers are taking note of her results, including government foresters tasked with managing forest harvesting.

The Salmon Forest project investigates how nutrients from spawning salmon are brought into the forest by bears and wolves and then taken up and shared by trees through the mycorrhizal network. Early results show that the fungal network structure is related to how many salmon return to the streams, as that drives the amount of salmon remains brought into the forest to decompose.

Simard is working to develop a new philosophy called “complexity science,” hoping to change forestry practices to prioritize the ecosystem over the timber supply. It’s based on accepting ecosystem collaboration as well as competition: “Complexity science can transform forestry practices into what is adaptive and holistic and away from what has been overly authoritarian and simplistic.”

As Simard writes about the path forward: “By understanding [plants’] sentient qualities, our empathy and love for trees, plants, and forests will naturally deepen and find innovative solutions. Turning to the intelligence of nature itself is the key.”

Sarah Boon is a Vancouver Island-based writer whose work has appeared in The Rumpus, Longreads, The Millions, Hakai Magazine, Literary Hub, Science, and Nature. She is currently writing a book about her field-research adventures in remote locations.